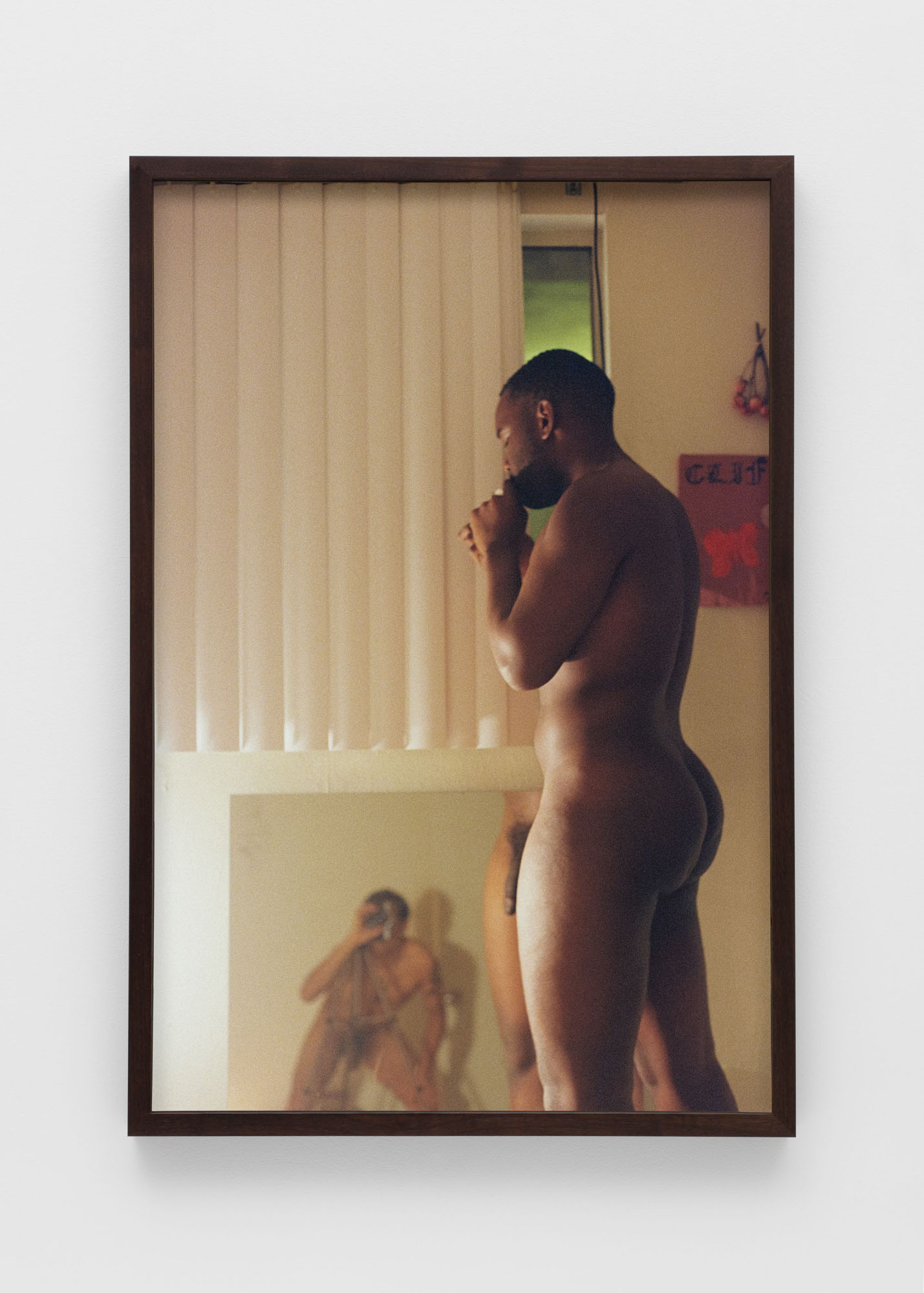

Clifford Prince King's photographs, writes Zoë Hopkins, "emerge from the everday intimacy experienced between young Black gay men in the artist's life... A self-taught photographer, King looks to the textures of his everyday life to animate his photographs. He takes pictures of friends, lovers, and acquaintances, many of whom have personal attachments to the sites where they are pictured.

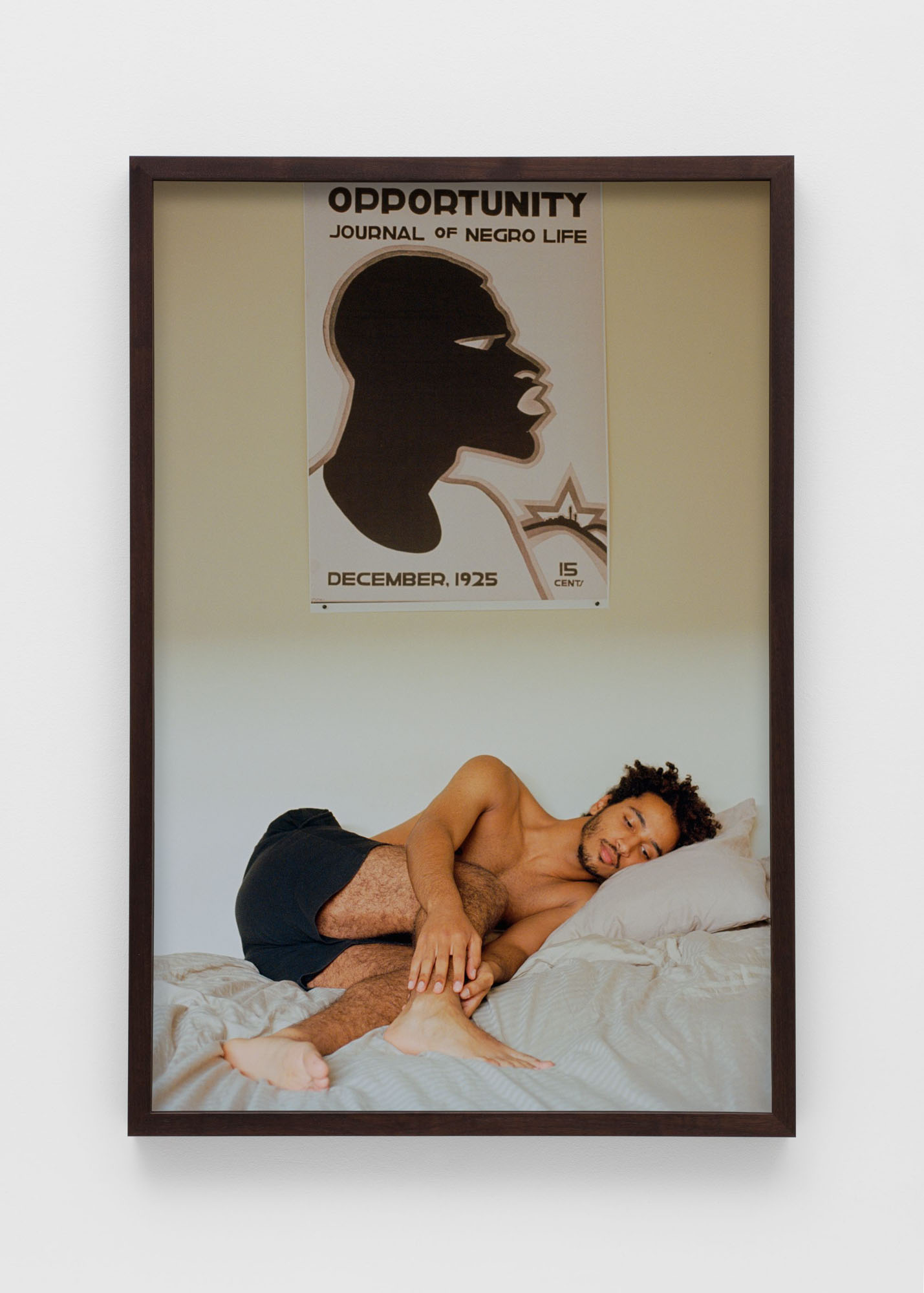

King approaches photography as a means of building an archive of tenderness: for him, it is a diaristic practice of recording his life as it is shaped by the people and relationships in it. While the works are deeply personal, they also extend an invitation to young people like King who are searching for images to identify with. They are havens of private existence and desire, yet they are also portals through which viewers can locate a sense of belonging.

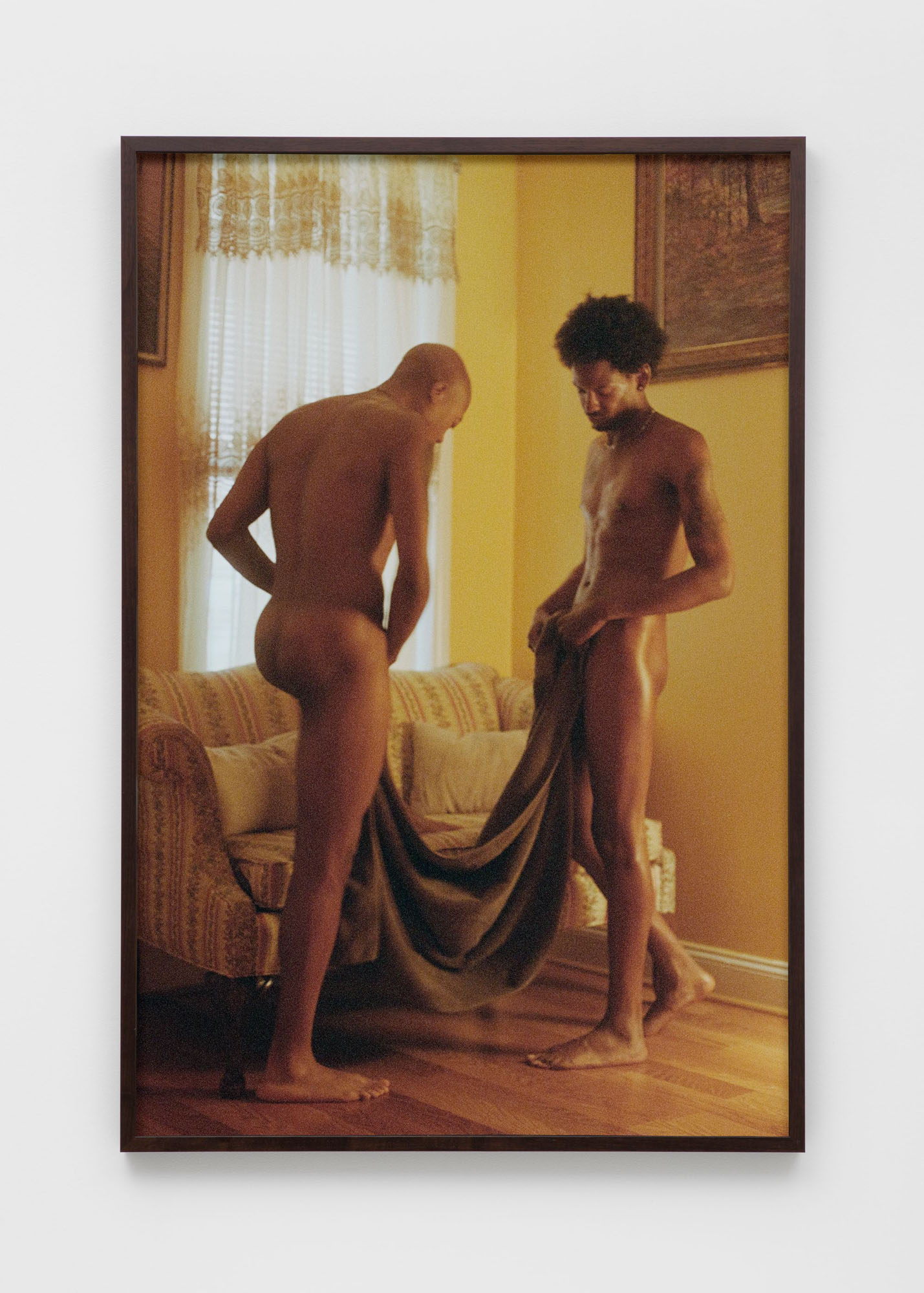

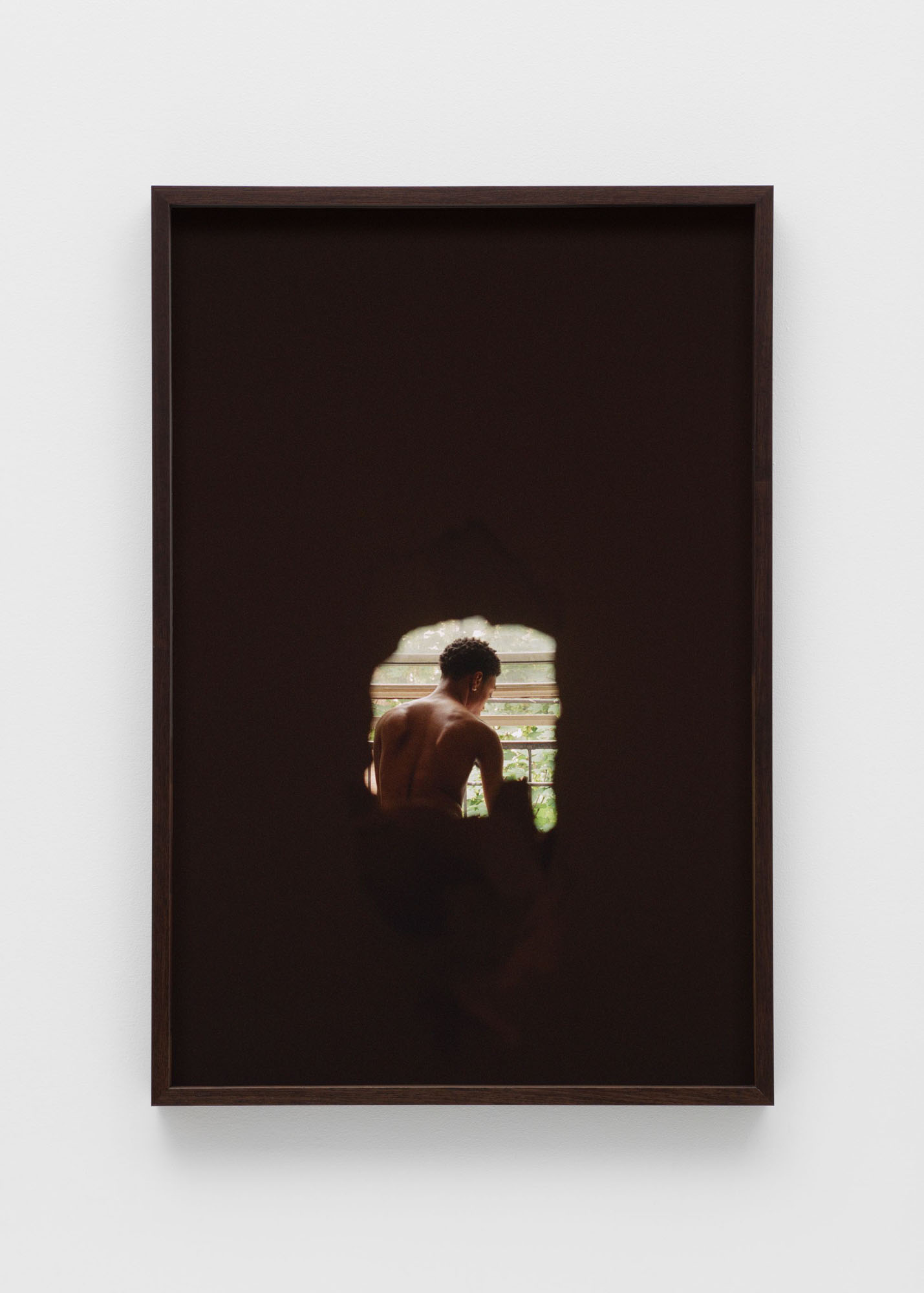

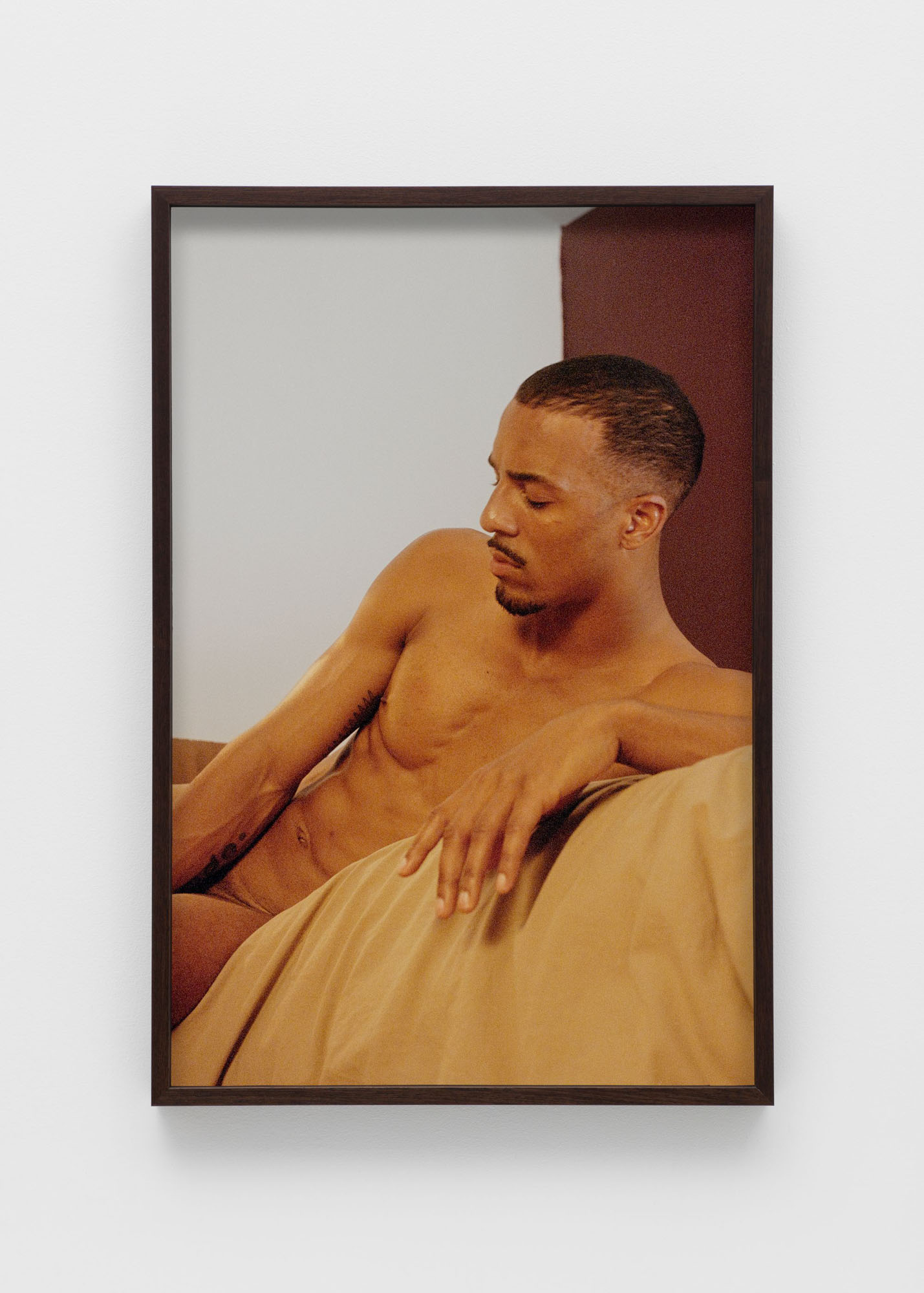

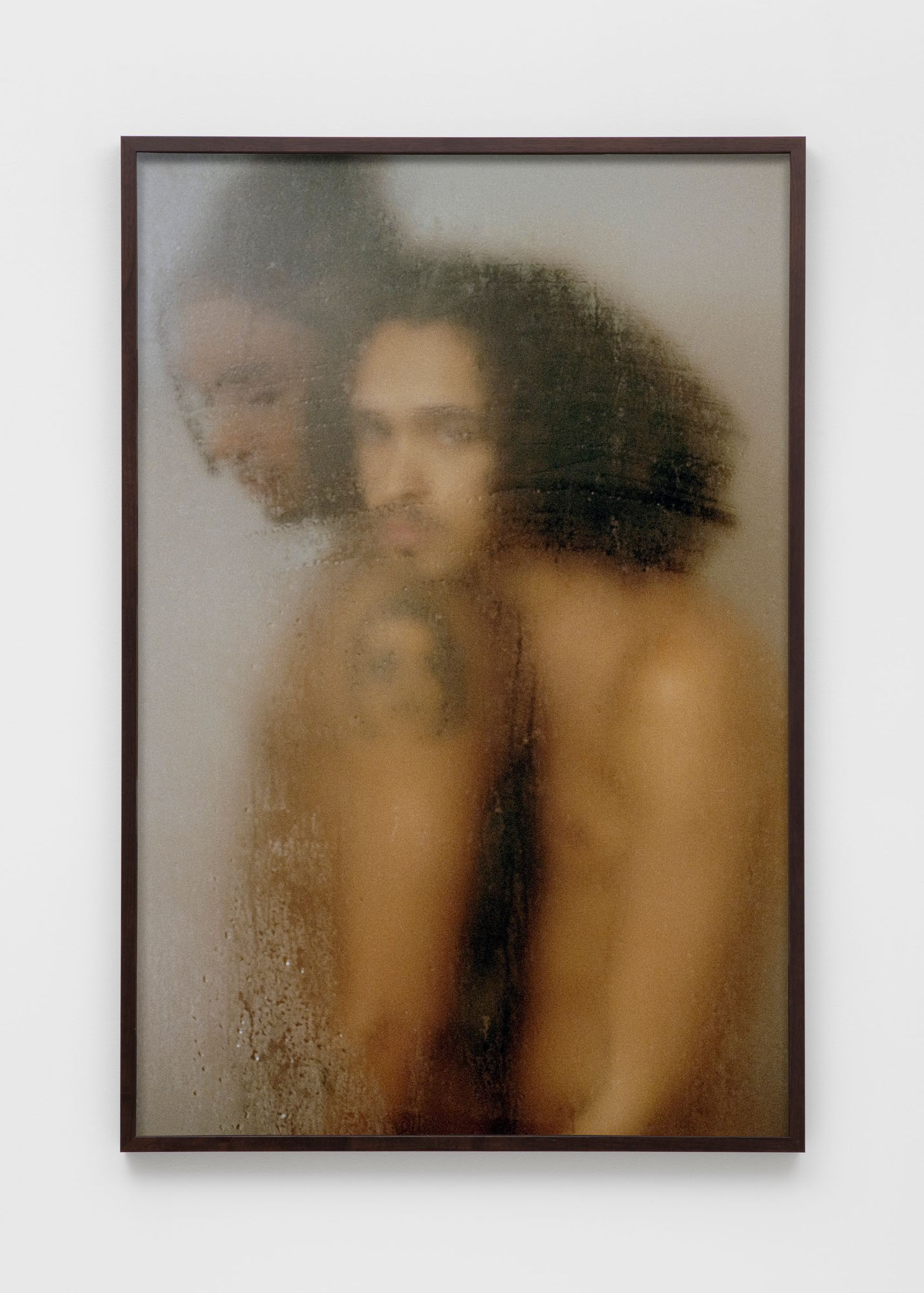

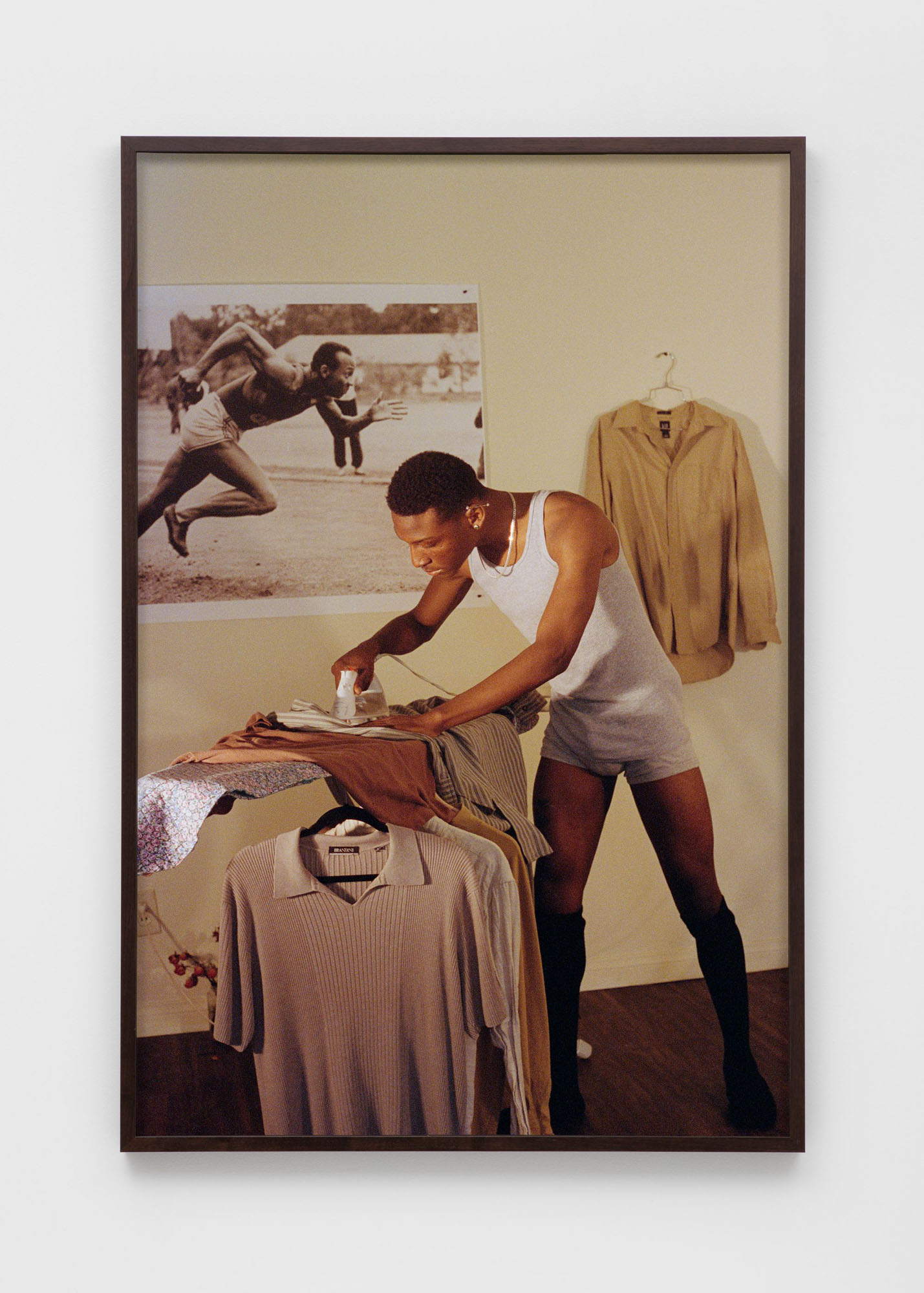

And indeed, King’s photographs are inviting to gaze upon, soothing the eye with a visual frequency that might be likened to a sigh. Places are imbued with a luscious quiet, and figures caught in a haze of contemplative stillness. Shot on the same film camera, which the artist has been using for eight years, these images share a painterly aesthetic that conjures the feeling of being in a daydream or soaking in the early morning sun. Pastel hues, soft light, and a balmy sense of tactility pervade, bathing the photos in a subdued aura of calm. The domestic interiors that appear in King’s pictures are cloaked in dewy beige, and bare skin—which takes on a range of brown tones—glows with a smooth luminescence that also strokes bed sheets and curtains.

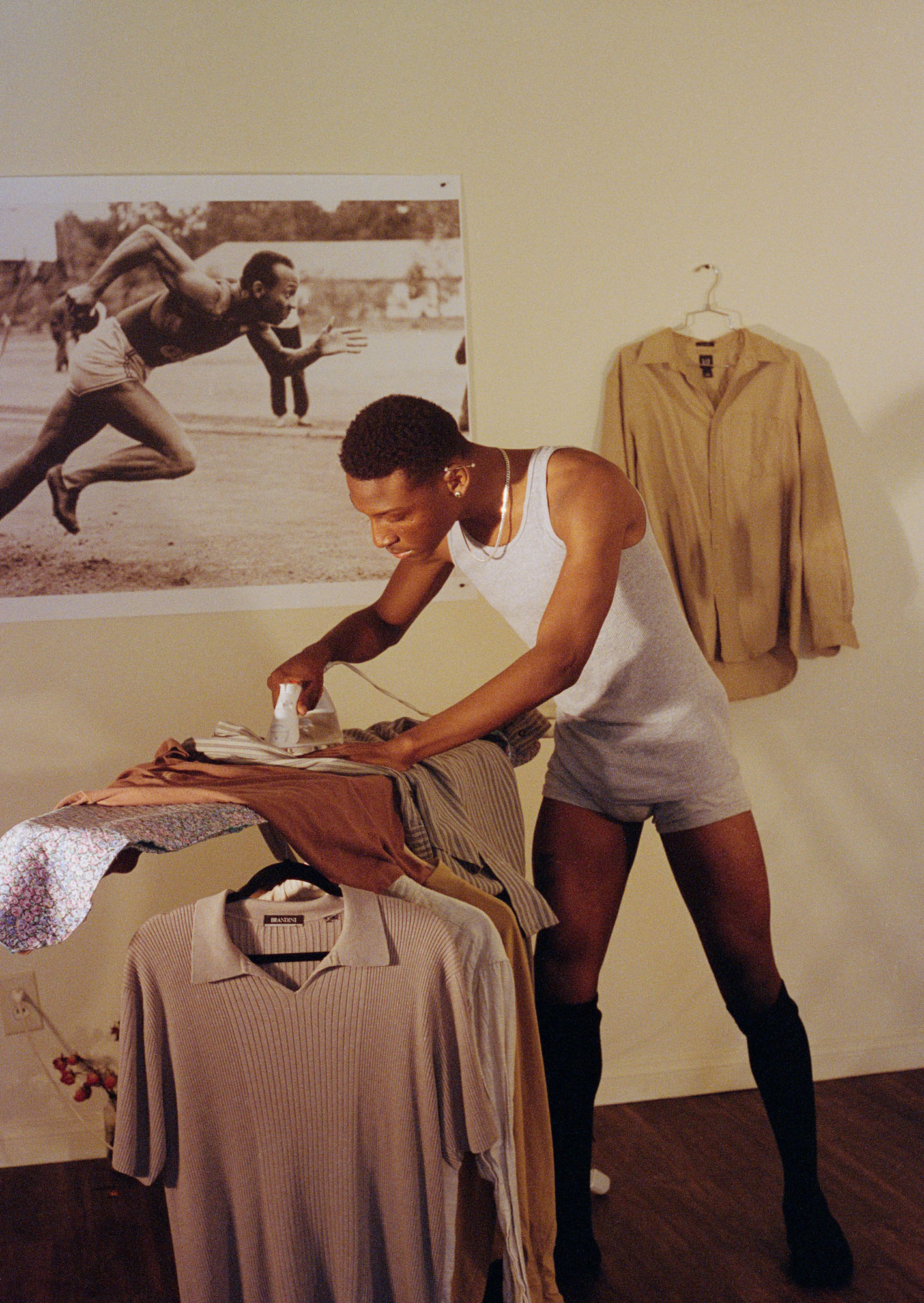

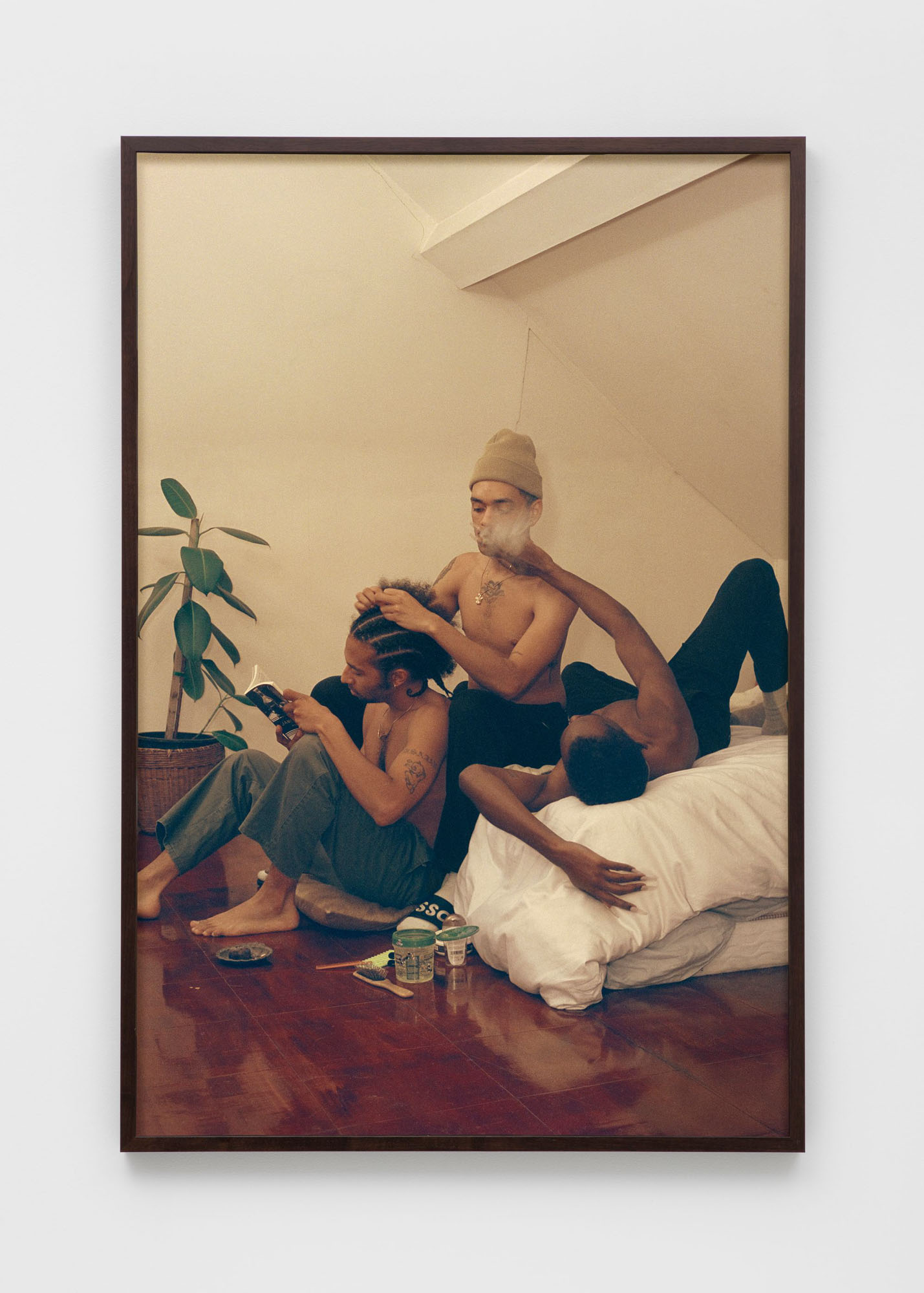

Though most of King’s photographs are staged, they are hardly theatrical. They are timelessly scenic and compositionally advanced, yet full of the raw vulnerability of real life. The choreography of the pictures maintains a relaxed tempo, and people in them are shown caught in moments of casual yet graceful unburdening: braiding each other's hair, embracing in the shower, or ironing in solitude. King pictures people as they are, in the comfort of their own being. Their presence in these pictures is just so. It does not exist in response to any presumed gaze from the outside: rather, they are in the folds of their own world, and most of the time appear utterly unaware of the camera. Faces and bodies are photographed in profile or turned entirely away from us and toward one another. Or they are simply caught in their own ruminations, eyes closed or turned downward in meditation.

Domestic space is vital to King’s vocabulary of intimacy. Rather than working from a studio, he photographs in the environments he moves in and out of, including his own apartment in Los Angeles and those of his friends. His camera often finds itself in bedrooms and living rooms where there is ample room for a queer erotics to take place. Above all, he wants to photograph people in places that are reflective of their own lives, where they can soften into their most capacious ways of being.

The title of the show, Hush-a-bye Dreams, comes from Nina Simone’s 1969 Music for Lovers, a ballad of amorous and bucolic imagery that Simone’s voice pierces with incredible intensity. “There is music for lovers to be found in the sound of a sigh. And there’s music for lovers in the dreams of a hush-a-bye child,” she sings in her thick, melancholic contralto. While King’s photographs have nothing to do with children—in fact, they unfold in a particular province of adult queer desire—they are undeniably lovely with the quietness that Simone describes, the hush that leads us into the private sanctuary of our dreams. Indeed, King’s frames are cradles of intimacy, worlds of primordial tenderness cast in gold light."

Hush-a-bye Dreams is currently on view at Gordon Robichaux in New York and coincides with an exhibition at the Kleefeld Contemporary Art Museum in Long Beach.

A recently published monograph of the artist’s work titled Orange Grove was recently published by TIS books.