Aberdeen, situated in the northeast of Scotland, is known as the “Granite City,” and if you dive deeper into its colloquial nicknames, you will also hear it referred to as the “Silver City with the Golden Sands.” What is immediately striking is the gray everywhere, a city of Victorian, Edwardian and Brutalist architecture butting up and existing right next to each other. Although centuries apart, the commonality of concrete and granite make them seemingly perfect peers. It works together. Brutalism is, indeed, brutal and harkens to the UK’s post-war redevelopment, whereas the centuries old structures feel unharmed by time, and preserve what was known as a glorious era of British world power. Where Brutalism is by its nature anti-nostalgic and future-forward, Edwardian was by definition an aesthetic that looked back. Yet somehow here, they exist in a harmonious dichotomy. That is the thing with granite; it feels so solid, so permanent, so infinite. These structures of Aberdeen, no matter their intent or architectural era, seem to turn time inside out; they head back and forward, their existence ever-lasting in their firm foundation. They are both rigid in form and aura. Ironically, if not the perfect metaphor, you are not allowed to paint on the granite of the city. It is to remain unmarked, unchanged, unresponsive to the changes of the city around it.

To consider granite as a representation of the power that history holds upon our psyche, as a characterization of law and order, an unrelenting form that the citizenry cannot or is not allowed to change, weighs heavily in Aberdeen. To an extent, this weighs heavily upon how we look at power in cities around the world. Who owns the space? Who dictates the way we can change such foundations? How can we loosen the screws of formality and form?

Martyn Reed, the founder of the renowned Nuart Festival, is also keenly aware of the rules of a city, that certain surfaces being off limits is a metaphor of the rules that govern our daily lives but also govern the power structures of contemporary art. Nuart has always been about that essence: finding the gaps in the system where street art, graffiti, contemporary muralism and a little bit of creative vandalism can exist and flourish and create its own narratives. When Reed first came to Aberdeen in 2017—2019, with a few additional curations in the “in-between” years and now returned for a full program in 2022, that granite was a surface that was unavailable to paint on, he had to find the proverbial cracks in the system for muralism and street art to exist here. “In Aberdeen, if the state stuck a chunk of granite down, anywhere, it's staying forever,” Reed told me recently. “There’s an authority there that I felt could be challenged. That granite is a representative of church and state power. Us commoners take the car parks and back streets.”

This idea resonated with me until I realized that this year’s Nuart Festival was also given a metaphorical gift for its 2022 edition. In the middle of Aberdeen lies a stunning old structure, the home of the Aberdeen Art Gallery, with open court and granite columns and a construction date of the late 1800s. In previous years of my visits, the museum was under renovations, closed to the public. It felt like a shame that, in the midst of one of the world’s great street art festivals finding a home on the streets of Aberdeen, the museum itself was unavailable. And yet its location, in the direct heart of Aberdeen, seems quite remarkable as the city of formal and imposingly constructed buildings surround. The museum is now open 7 days a week, it’s free with recommended donations, a gift shop and cafe give way to an open layout and public access. Art and ideas should be the means for changing the way we look at the world around us, where societal rules and granite may seem permanent but the art inside is evolving, educating, understanding. Where there is rigidity outside, there is a softness and flexibility inside. I couldn’t help but think how vital it is to have a museum so centrally located, the heartbeat and lifeblood of a city. This is not lost on anyone who uses the space.

Art has an interesting if not vital role in our new paradigm of post and present Covid life. Art exists between structures, both in their essence and true, unyielding physicality. Buildings and the laws that govern us are rigid; art is a representation of change and fluidity. Where buildings in both Brutalist and Edwardian or Victorian construction seem to exist forever in their very form, art is softer, susceptible to weather and open to evolution. Art allows for new ideas to run through a place and the minds of those living there, it doesn’t look back with nostalgia but back for strength and resolve that the future can, indeed, be more open and inclusively rich.

Here is where the people who inhabit a city come into play, because for what has seemed like an eternity and has really been less than a 1,000 days, we have been pulled back in time and desperate to know what a future holds for us. These two architectural developments had me thinking about how cities evolve, and how the people who live in them need their cities to function and serve them. What the pandemic did, in most places and surely in most city centers, was take away our public space and the uses we had for them. For over a year or more, we stopped walking to work, we didn’t converse at the local shops with neighbors, we didn’t travel to new places and find nuances in cities that weren’t our own. The idea of the city center and the city as a meeting place, a place of exploration and accidental encounters that fill us with joy and pride, faded away. The buildings, those of granite and cement, remained fortified to the ground, but our memories of how and why we used them, was up in the air.

As the Nuart Festival returned in full capacity in the summer of 2022, Reed came with the theme of “reconnecting.” This is both smart and multifaceted. What are we reconnecting with? To each other, yes. To the city, of course. To the idea of viewing a city as a living, breathing place? Absolutely. To reconnect with art in the public space, to have a chance encounter with a new stencil work on your street or a mural in the center of town? These are all true. Reconnecting meant returning to the promise that in all our uncertainty we had over the last 3 years, that the anxiety we have felt that our place in the world would never be the same, that beginning to have conversations once again with our fellow citizens, artists, friends, colleagues and family could help reshape the spaces we live.

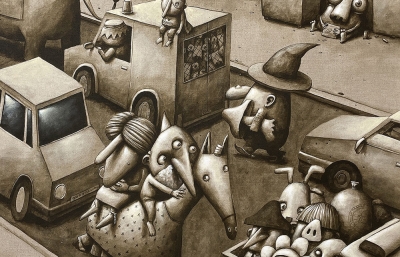

There were standouts all around the city from this year’s roster, which included Pejac, Erin Holly, Elisa Capdevila, Martin Whatson, James Klinge, Miss Printed, Jacoba Niepoort, Slim Safont, Nuno Viegas, Mohamed L’Ghacham and Jofre Oliveras. And within that idea of reconnecting, the likes of Holly, Capdevila and L’Ghacham took an internal approach, painting large murals of dreamscape intimacy and home interiors. Each of their murals, from Capdevila’s woman in bed looking out of a window to the blue sea, Holly repainting a dream bathroom found in a home catalog and L’Ghacham taking a found photo of a family at the dinner table and blowing up to a multi-storied painting, are representative of what is both lost and desired in our uncertain era. What we hold onto are the dreams of change and better days to come, our desires are for life to return, but there is both an understanding that a vulnerability needs to be injected into the heart of our cities so we can all heal, dream and connect, together.

I’ve always loved that murals have a way of looking forward while facing the elements of time in a way fine art doesn’t. Murals fade with the weather, get painted over, get reimagined in the sun and bring a brightness if the weather is gray. They can serve as reminders of political eras, of the best of times, the worst of times, and gentrification, blight, shortfalls and windfalls. The people who walk around the murals each day change, too. They experience time and space unlike the structures around them. They converse at the grocery store, walk past a tiny stencil and 3-story Erin Holly mural on their way home. To meet friends for lunch and notice a new sticker on a streetlight pole. These pieces of art get taken down, buffed or picked away, but they are part of an experience that is both ephemeral and joyous, that amongst the rules of time and power, where we are told not to play and not to touch becomes our little playground for just a moment. With an art gallery at the epicenter of the Granite City, with muralism and street art creating a space for expression where rigidity seems to have just taken hold, the reconnection with a city’s potential has just begun. —Evan Pricco

Visit https://2022.nuartaberdeen.co.uk for more information