56 Henry is pleased to present EAT ME, an exhibition of new paintings by Jo Messer, on view through June 4, 2023. EAT ME marks Messer’s second solo exhibition with the gallery and occupies both gallery locations, 105 Henry Street and 56 Henry Street.

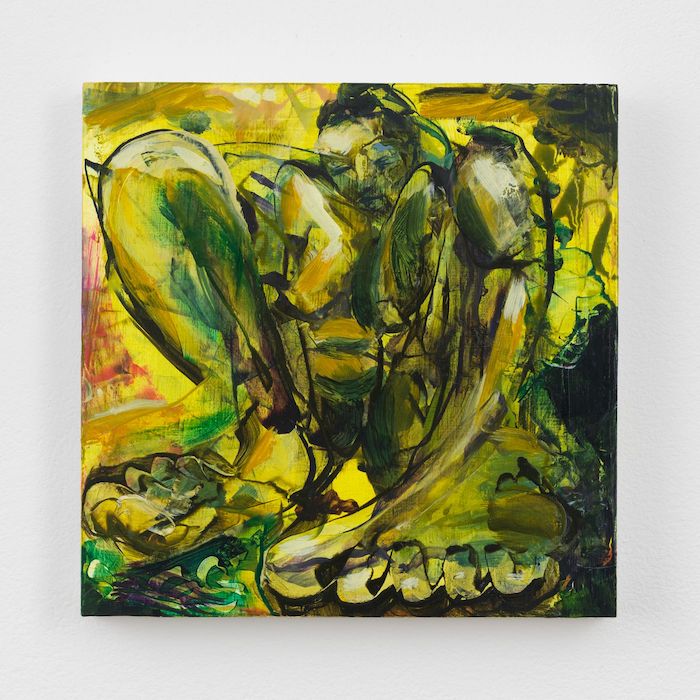

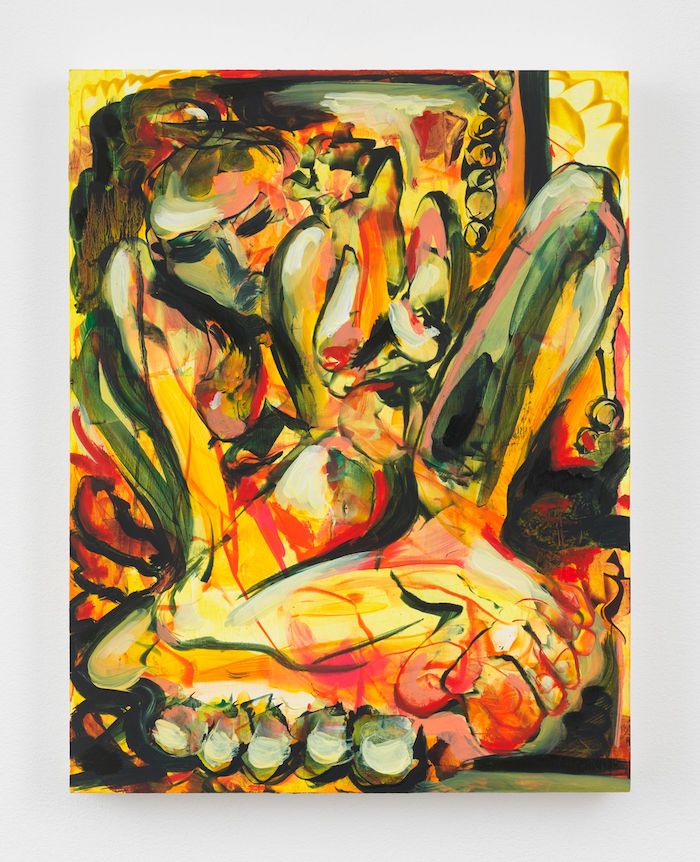

Jo Messer maps bodies in liquid space. In her new paintings, feet keep us grounded; plump toes line the bottom of most canvases. Elsewhere within her atmospheric, brushy environments, these spherical forms reappear as oyster shells, fragmented toes, and micro-portraits.

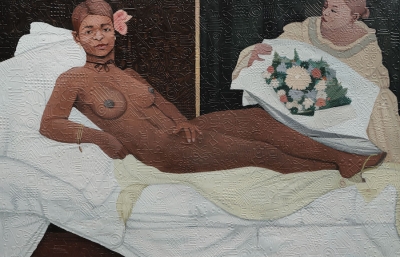

In EAT ME, Messer ushers us into a verdant cavity between abstraction and representation. Within a thicket of brushstrokes, precise flecks of white highlight the tips of foreheads, shoulders, knees, and toes. Messer’s contorted figures reflect a deep understanding of the history of the nude and the simultaneous objectification and idealization of women—of their purity, their sexual desirability, their availability.

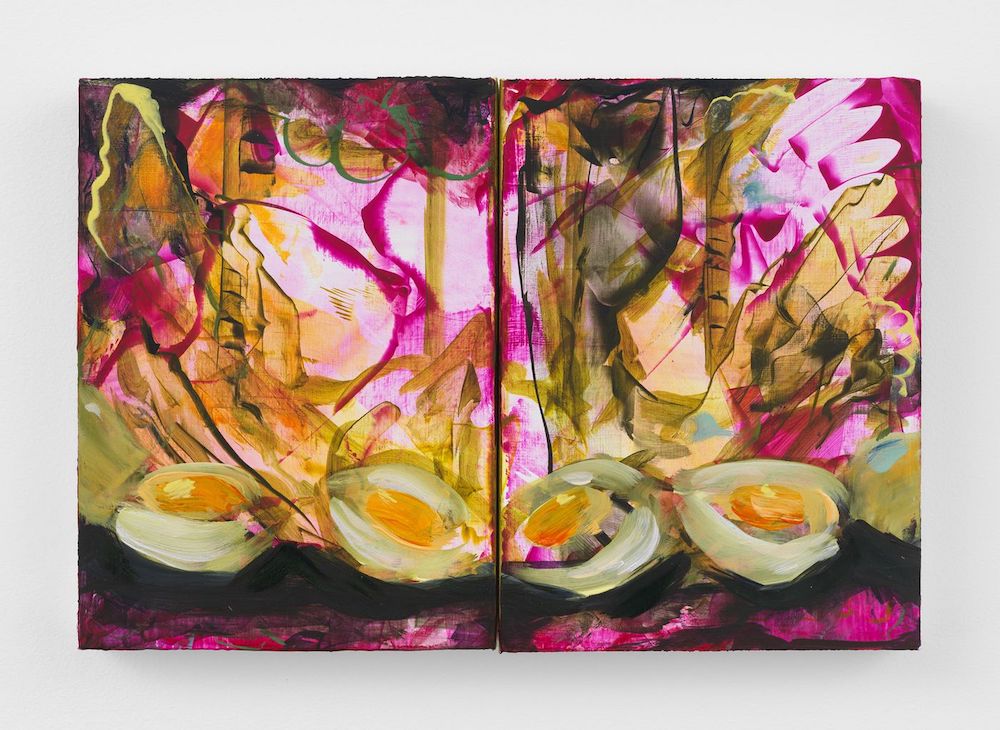

The exhibition’s title reveals the subtext to Messer’s imagination and serves as a droll dare to challenge the sexual character of her work as the vocabulary around food and eating has long been borrowed to articulate attraction. In a four-panel polyptych titled Eat me, a nude woman, shown multiple times over, sits on a large oyster shell, her body erotically arranged. In another large-scale diptych, Bib on the floor, extra crunchy, she slouches on a bed of lettuce, a green leaf artfully covering her pubis. Smaller paintings throughout echo this visual theme. The limbs of Messer’s women hang like the tails of prawns on a tray of ice in a seafood tower. They are arranged like delicate crudités in beds of decorative greens.

The paintings—contemporary in their figuration, use of color, and movement of paint—reference the romanticization of the female form in the early Renaissance. Specifically, The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–1486) by Sandro Botticelli, where the goddess Venus stands in a seashell, her long blond locks tastefully arranged around her anatomically improbable naked figure. In Messer’s world, her oyster shells—gnarled, bumpy, and uneven objects—add a necessary touch of imperfection to the pedestal on which these women are placed. If Botticelli’s Venus represents an idea of innocence and virginity, then Messer’s women are decisively not that.