Perrotin are pleased to present the first exhibition of New York-based Japanese artist Susumu Kamijo at its Paris gallery. For the occasion, the artist showcases a new series of paintings exploring the psychology of the canine. The dog (canis lupus familiaris) is an ambiguous creature. In ancient Egypt, it was considered a psychopomp, a soul guide, leading the dead to paradise when it was not guarding the gates of hell. Domesticated, altered, and transformed, it nonetheless remains unpredictable today, its primal needs reminding us of this sick nature that threatens us with pandemics and climate change. Initially a hunting dog, the poodle gradually became a pet and then an accessory, exhibited in portraits as a symbol of luxury and fidelity.

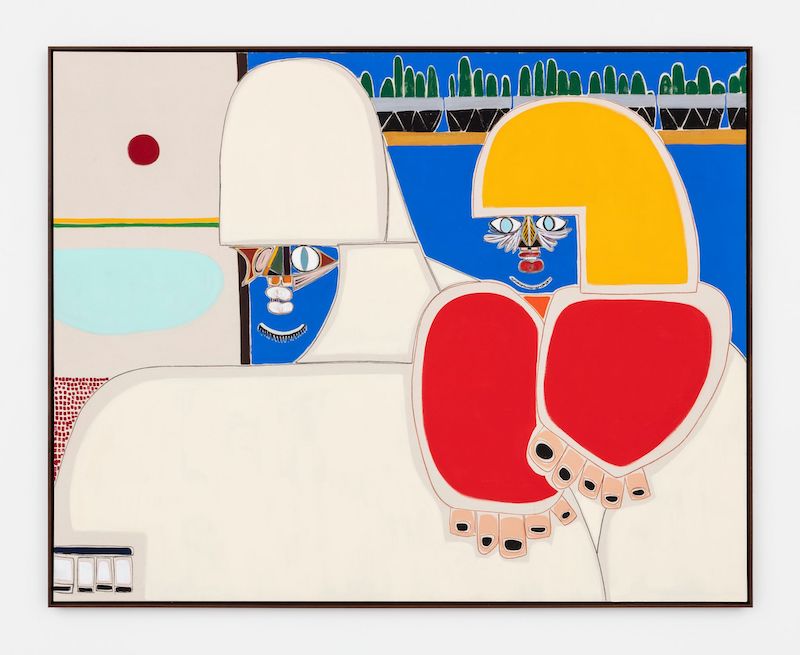

Susumu Kamijo discovered these animals – their world and extravagant codes – in dog competitions. The show dog is a symbol of artifice and eccentricity (from its behavior to its coat), and the splendor of dog competitions is at times reminiscent of the fashion world: the sophisticated poses of Kamijo’s models, their caricatural looks and accessories – firmly placing the dog on the side of culture in the perennial nature/culture debate – are reinforced by bold color palettes that resemble fashion magazine covers. In these imagined portraits, the dogs are posing, haughty like Ingres’ bourgeois with the prestige of Tamara de Lempicka’s elites.

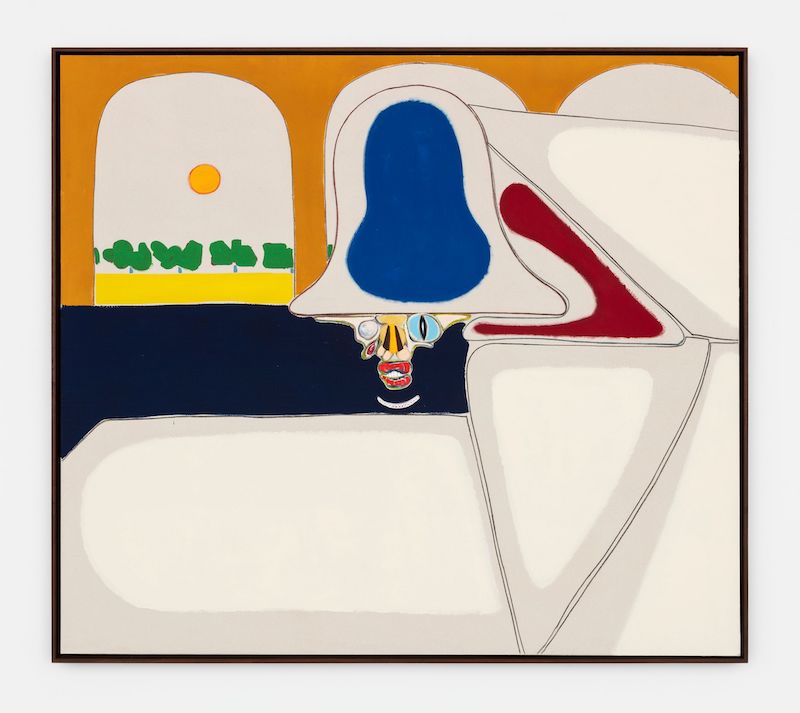

Kamijo’s poodles are no longer hunting companions – tamed and adapted – nor are they the distinguished accessories in portraits. In his work, the poodle becomes a clever device, a motif reminding us that Kamijo’s subject is first and foremost painting itself. It’s a classic method. Starting with a familiar element, he reproduces it tirelessly to the point that it becomes automatic, a register of forms and sizes requiring intuition to determine the arrangement of colors and its visual consequences. To slightly misquote Maurice Denis, “remember that a painting, before being a poodle, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.”

As a painter, Susumu Kamijo revives some of the explorations that led painting to the frontiers of abstraction, such as simultaneous contrasts of forms and patterns of color. In the history of abstract painting, a motif was often pushed to its figurative limits, and Kamijo’s poodles seemed until recently to follow in the footsteps of Piet Mondrian’s Flowering Apple Tree or Jawlensky’s Mystical Heads. Yet Kamijo’s latest series also moves in another direction, as it does not renounce figuration, striving for more complexity and psychology.

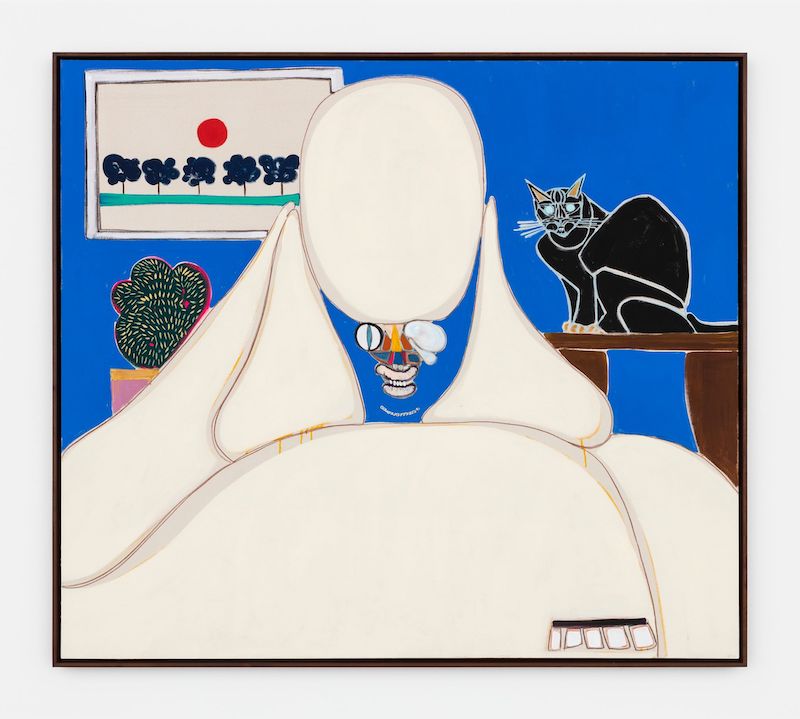

Even though the figures’ faces and mouths remain stoic, one is tempted to see a form of anthropomorphism. Kamijo introduces this psychological dimension by experimenting with minimalist but familiar environments with objects such as a vase or an animal skull, which, for the artist, evoke museum displays. An open window or a painting within a painting turn the surroundings into a reassuring motif. Delving into the depths of the image, he divides the composition into regular legible planes in which he places his creatures, an in-between, keeping the viewers at a distance while also inviting close observation.

This comfort of the domestic environment is a key factor in his latest explorations; the living room that humanizes his models is influenced by Francis Bacon, and, as in some of Henri Matisse’s paintings, the figure merges with the décor to create a harmony of composition and a poetry of the everyday. This intrusion of detail, precise and powerful, is also a homage to the Japanese filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu, referencing his extraordinary indoor shots with their deliberately low and persistent angles, celebrating everyday life by finding beauty in the banal and philosophically revealing moments of life punctuated by the frames of doors and windows.

Even though he acknowledges the importance of classical painting and its masters, Susumu Kamijo’s practice cannot be limited to these traditions. The paintings have to be taken for what they are, hallucinatory portraits of poodles that deliberately play with the conventions of portraiture, between homage and mischief, because after all, as he claims: “Life doesn’t make sense. Just live playfully. That’s my way of dealing with life.”