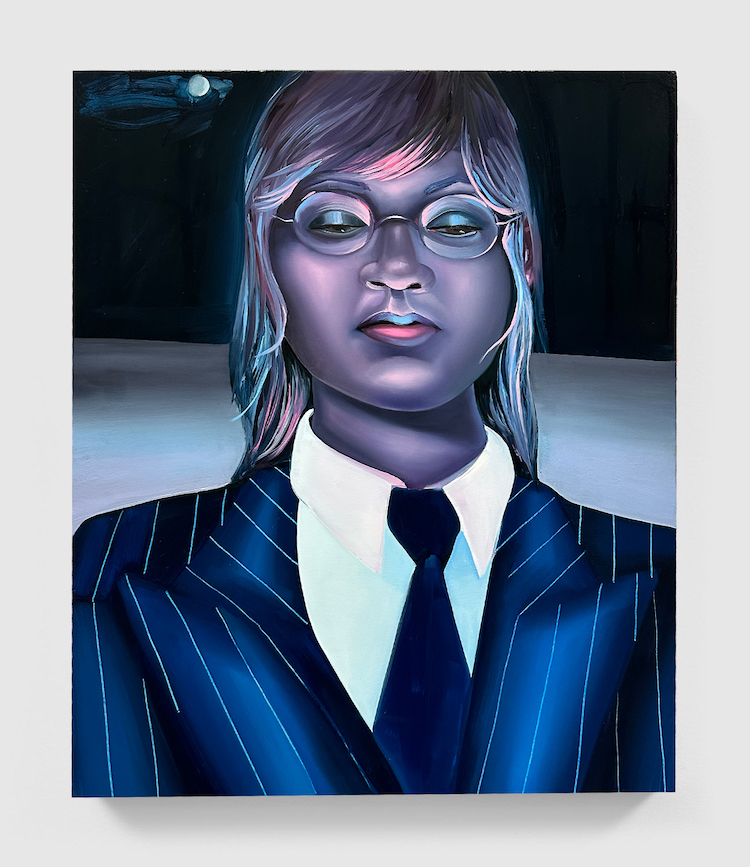

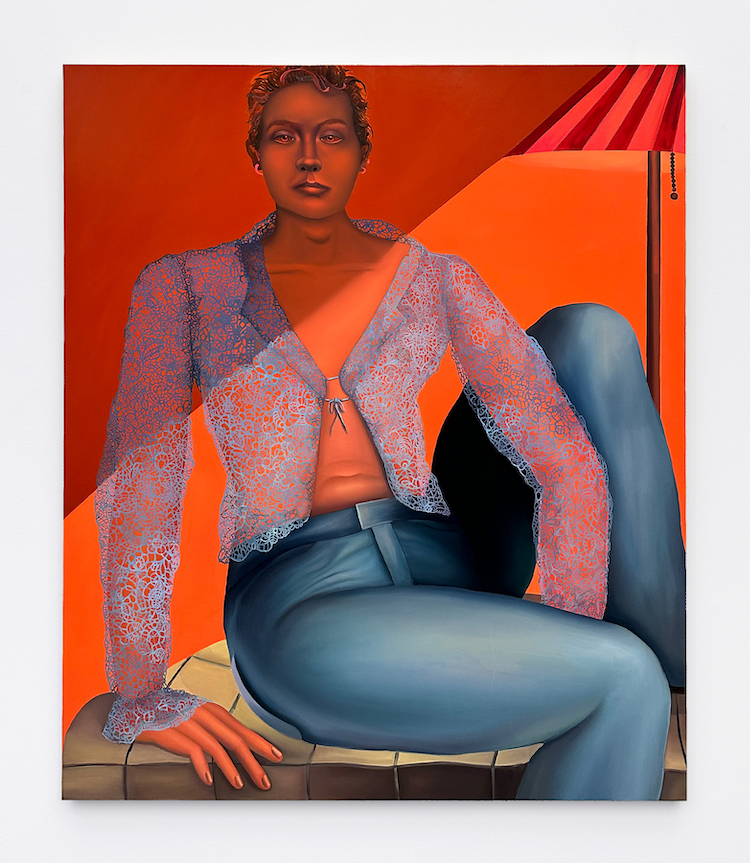

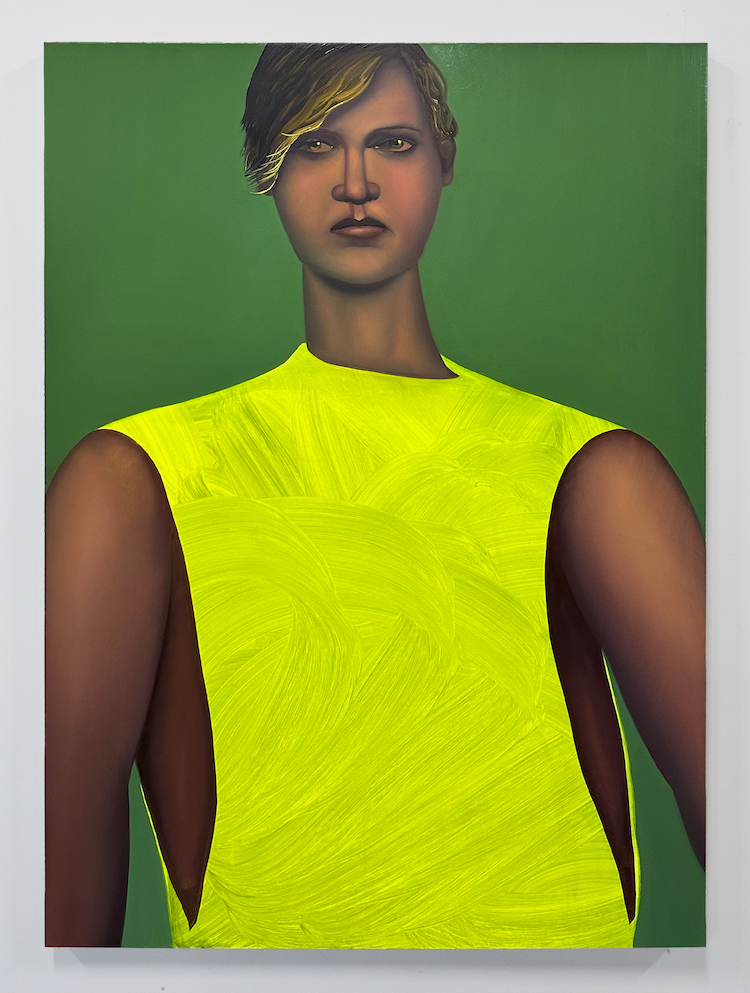

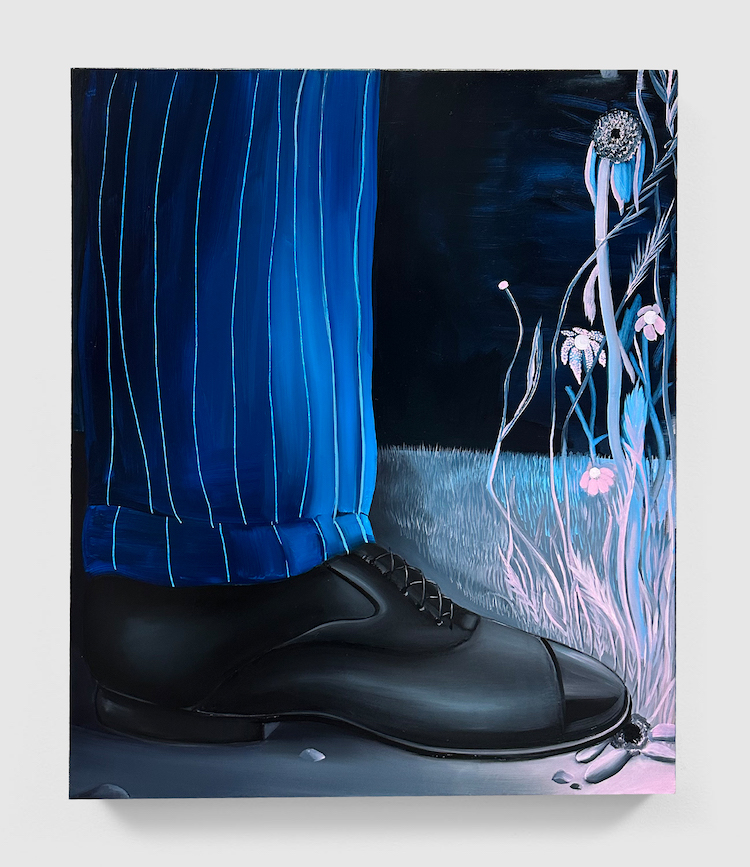

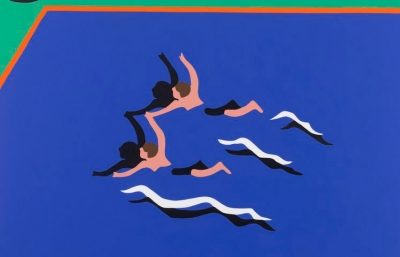

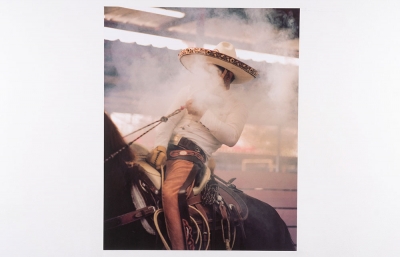

Coady Brown’s work occupies a singular position in contemporary painting practice. Her complex works are simultaneously of the moment, yet also contain echoes of art historical motifs. One of the most promising painters to emerge from the United States in the past decade, Brown paints scenes of emotional depth that confound a cursory visual analysis. Her meticulous technique as well as an astounding sense of color, light, shadow and composition create an initial visual impact; however, on closer examination her paintings unfold through elusive details, creating subtly charged scenes that appear at once ordinary and extraordinary, horrific and sensual.

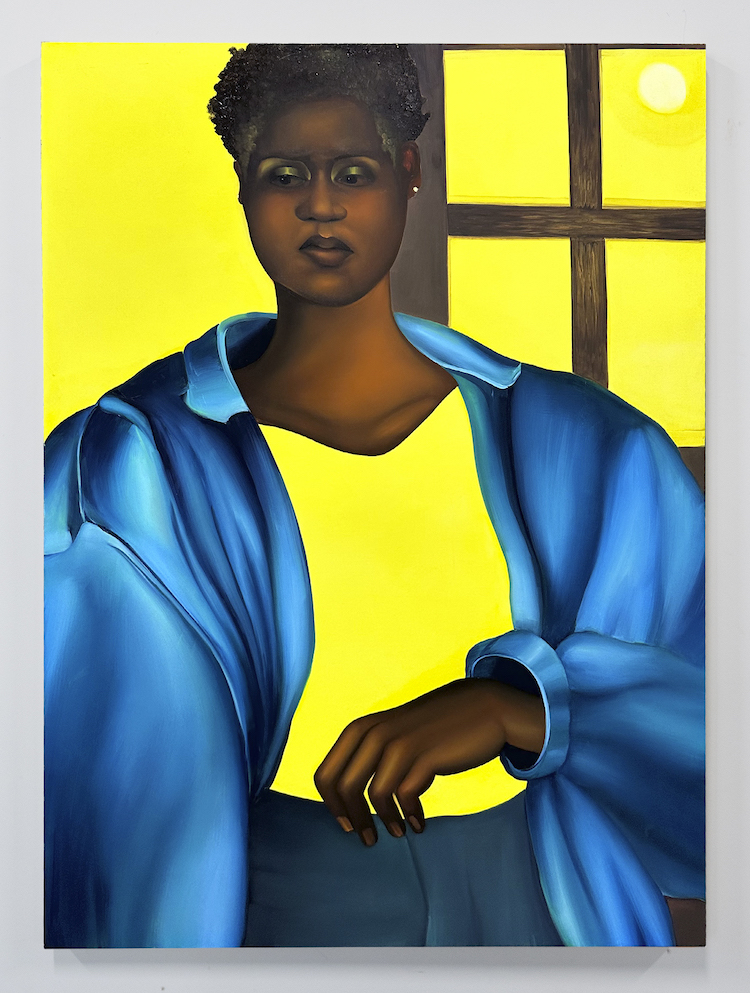

Brown’s second solo exhibition at STEMS gallery focuses mostly on images of women—a mainstay of her oeuvre in recent years. In her paintings the artist captures the intangible subtleties of female and female identifying existence. The women in this new series are inspired by people that the artist observes, especially in the streets of Philadelphia, the gritty East coast city where she has lived and worked for many years. Images of self-presentation, the farce and humiliation of it, is what Brown captures so fiercely. The title of this exhibition, My Eyes Burned Bright, refers to the vivid impact of looking at a woman or feminized person, or feeling their gaze returning. It is also the title of a painting in the exhibition. In this work and 10 additional new paintings, Brown’s women observe and are observed in the tragicomedy of everyday life.

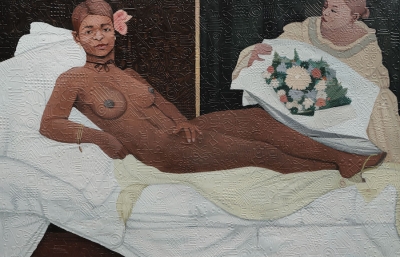

Since classical antiquity the female subject, in art as well as in life, has been the site of intense scrutiny and conflict. The dichotomy of chaste Madonna or tantalizing whore has played out throughout the history of art as well as other cultural forms including cinema. Since the advent of feminist art practice, the conventional idea of female gender has been disrupted to include a spectrum of possibilities. Feminist art celebrated the muck and the darker side of female experience, harnessing new materials to convey these controversial ideas, casting painting and sculpture as retrogressive mediums. Brown continues the critical feminist tradition, reinvigorating it through the medium of painting. Her figures perform female gender, embrace it, and at times magnify cliched characteristics of womanhood. Some are resistant, irked, angry, or suspicious, celebrating the trope of the rebellious woman. Some subjects fill the frame with their faces painted in strong sculptural effects, reminiscent of Tamara de Lempicka. Other figures are voyeurs themselves, occupying the position of both viewer and viewed. Brown says that these new works are “inspired by [her] fears, fantasies, observations, questions, and inner conflicts.”

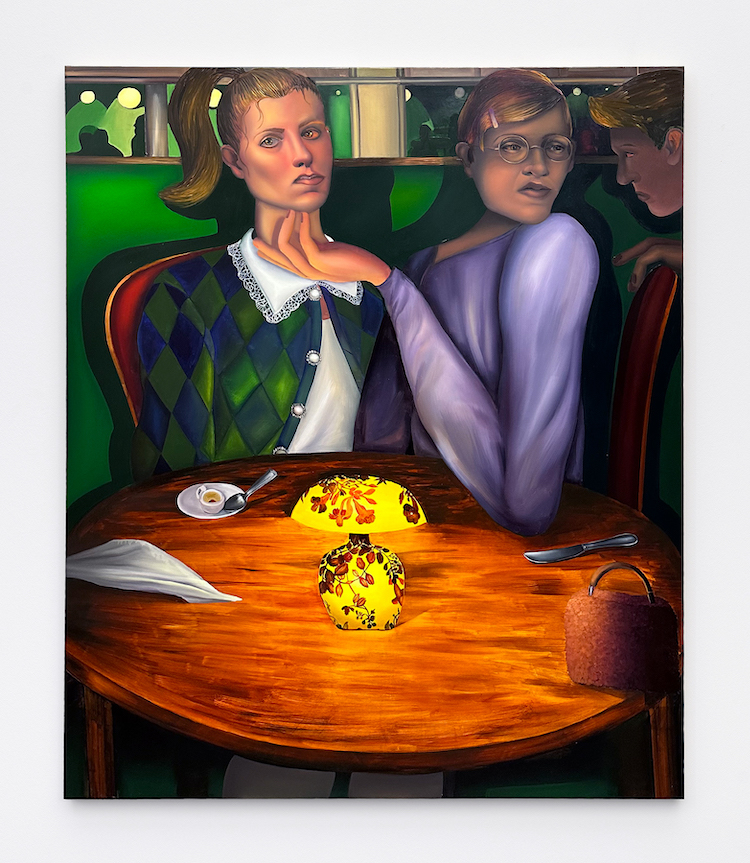

One of the touchstone paintings in the show, Chaperone is an evening scene, played out in a dimly lit, claustrophobic restaurant that would not be out of place in an Otto Dix painting. Three figures jostle for the viewer’s attention in a strange power exchange: a ponytailed young woman, a chaperone who occupies the central section of the canvas and seems to tickle her charge’s face, and a waiter who bends into the scene to interrupt the enigmatic, uncomfortable dynamic of the women. The acidic palette of the chaperone’s purple shirt and young woman’s blue argyle sweater that veers towards costume, as well as the elongated limbs and fingers of the figures, are reminiscent of Mannerist masters including Bronzino and El Greco. Through stylish artificiality and containment of the figures, Brown echoes a Mannerist sensibility, often presenting an enigma for the viewer to solve. In the foreground of the canvas, a yellow lamp, based on a Tiffany lamp held in the Baltimore Museum of Art, glows and hints at luxury. Collapsing references from different eras and movements, Brown creates a singular style.

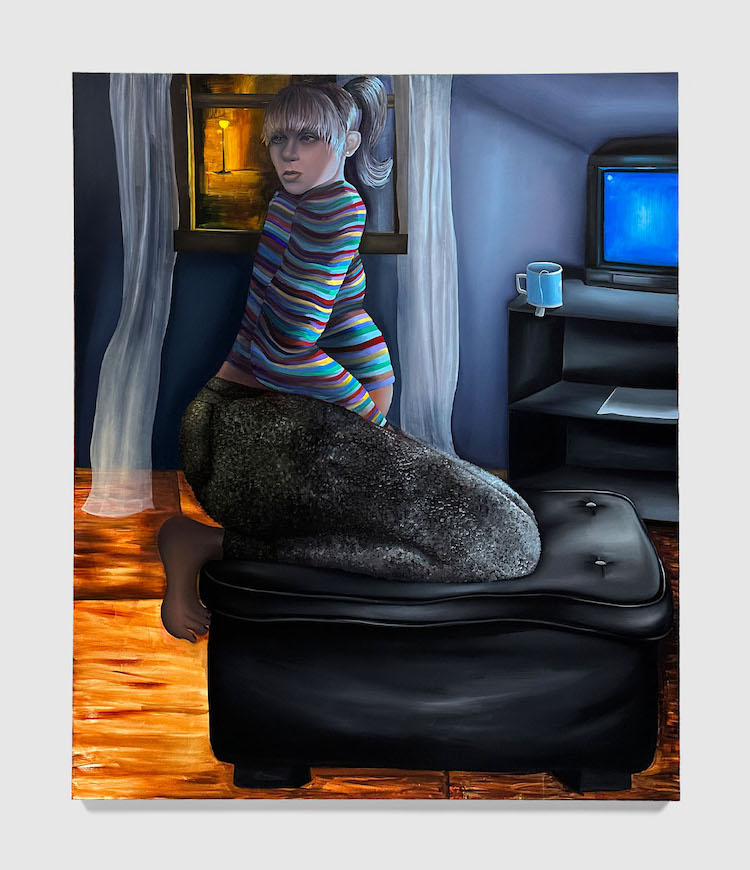

Visions of You embodies the schizophrenic nature of female experience. In this nighttime scene, a pregnant woman kneels on an ottoman with her head turned 180 degrees behind her, an impossible position only witnessed in films such as Beetlejuice or the Exorcist. Painting a pregnant subject is new territory for the artist as Brown asserts, pregnancy is “the ultimate sign of optimism in the future”. However, the impossible position of the head illustrates a more complex expression of this unique female condition. In Brown’s canvas, bliss and body horror co-exist. Further dualism is provided by the intense palette: an inherent tension is witnessed between the cold blue tones of the furniture, the figure’s clothes, the glowing television, and the walls, and warmer orange areas created by a lamp in another room, as it is reflected off of the window behind the figure’s head which casts a light across the floor of the room. These qualities of the dramatic may be understood in the legacy of film noir. Here Brown combines the creepy, ominous, cinematic feeling that she often embraces in her work with a more optimistic impulse.

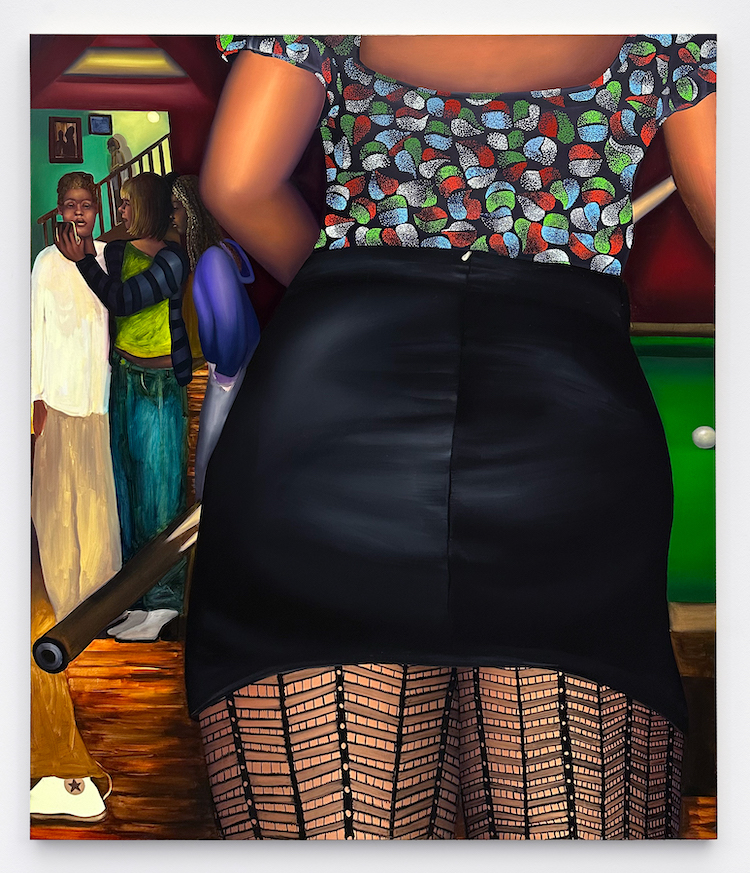

Last Shot and Fair Play are works conceived in conjunction. In Last Shot the female protagonist is seen from behind, in an awkward position, bent over a pool table. The white pool ball and the back of a pool cue signals the title of the painting, as the last shot that remains on the table. While her voluptuous backside and fishnet legs are adornments of female representation: we never see or understand who she is. In the background, however, the real action is taking place, as if the central figure is just a distraction for the viewer. The main narrative crux centers on three people in the back left corner of the canvas who are looking at images—the glow of the cell phone signals some kind of psychodrama. The figure in the white shirt is trying to collect herself. Brown describes this work like “moving through life when you pass someone on the street in a screaming fight and wonder what could possibly be unfolding ”.

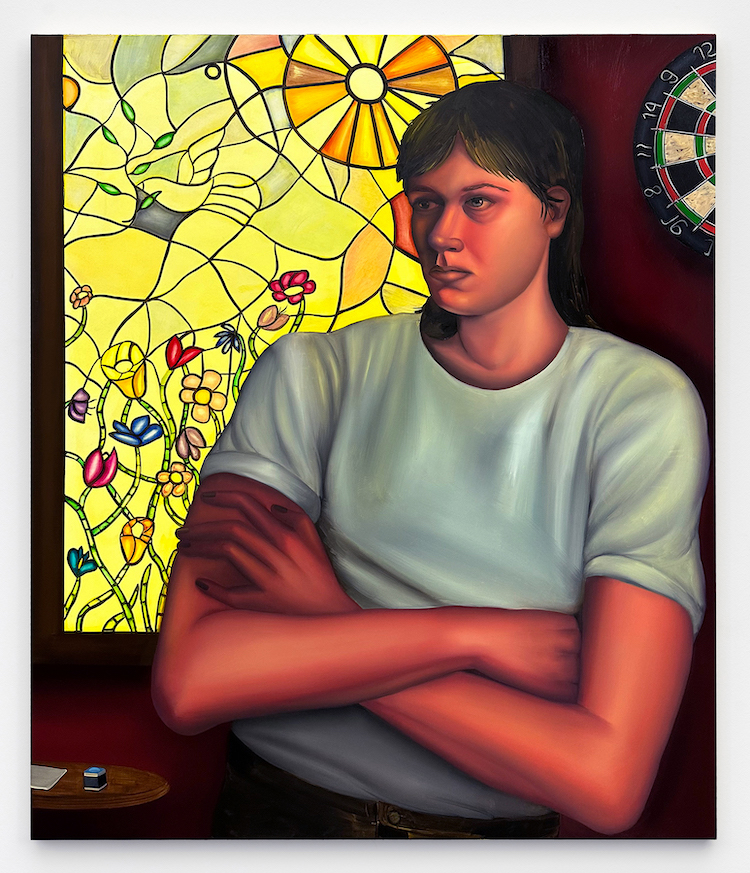

Fair Play is a related painting of an androgynous woman in a bar in front of a stained-glass window. The tiny de- tail of a pool cue chalk on the table indicates that this woman is watching the drama unfold in Last Shot. Brown gives other hints that the paintings co-exist: the wall color is the same in both works and the dart board and pool table is a logical juxtaposition, given the setting. Again, there are hints of Tiffany influence in the stained-glass motif that occupies a large swathe of the canvas. Embedded in this pattern, a dove suggests a spirituality that may be read as a type of memorial. Brown is interested in stained glass with its connections to spirituality, here turned away from the decadent appeal of Tiffany glass and aimed more towards the spiritual and the transcendent.

In each of the paintings in this exhibition, Brown evolves ideas around the gaze and the female experience in the 21st century. Since Laura Mulvey coined the concept in the early 1970s, the male gaze has been an abiding premise in both the history of art, as well as Hollywood and mainstream media. Brown acknowledges the female as spectacle, but also as spectator and creator. From a more empowered position, she paints unexpected works that confound and delight viewers. Some women in her works are the objects of our gaze while others gaze on actions that are never clear to the viewer, watching something unfold on the periphery of the canvas or something outside the picture plane all together. To look and be looked at is one of the basic delights and dreads of human experience. —Kathy Battista