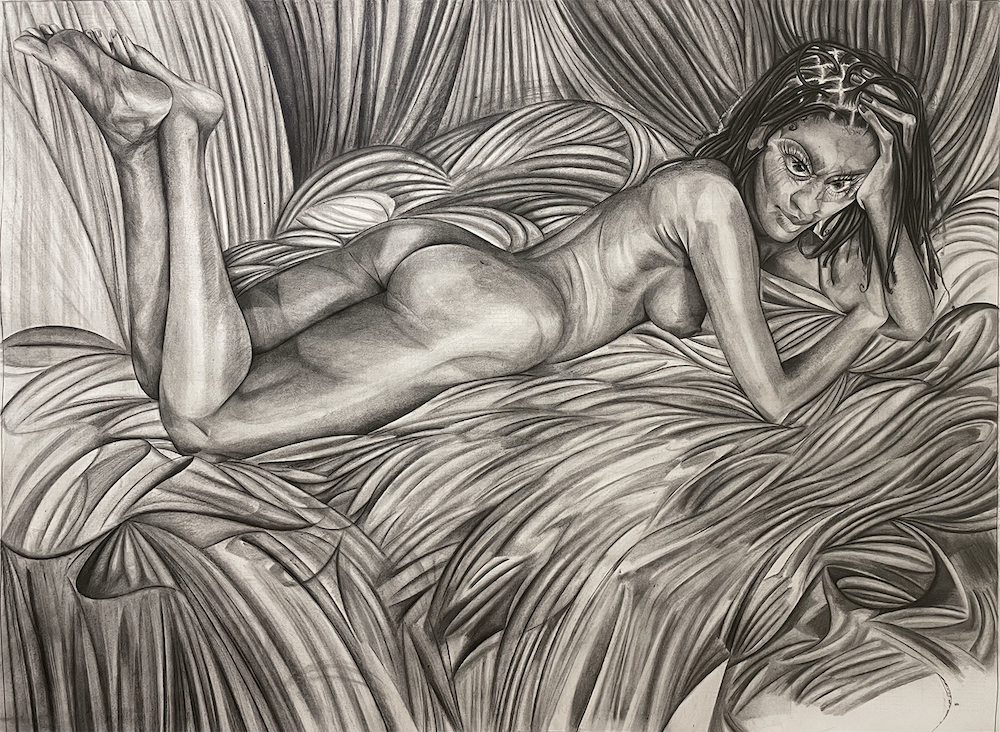

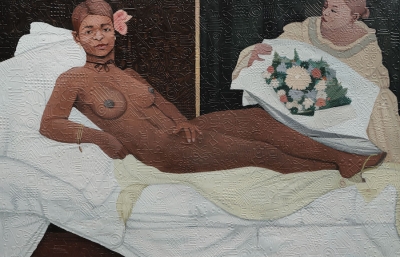

A nude female figure rests in the top half of a horizontal composition. She looks at us from the comfort of her bed, a nest of silky sheets not unlike a stage. Sheets become curtains, which, along with her gaze, pour over the edge of the frame. She is looking down on us, from atop a tall waterfall, boldly reclining. The figure makes herself familiar. She wills to mind images of female nudes from before her time — Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ Grande Odalisque, Manet’s Olympia, Gauguin’s Spirit of the Dead Watching — and more intimately: Carrie Mae Weems’ Portrait of a Woman Who Has Fallen From Grace, Deana Lawson’s Otisha, and Mickalene Thomas’ portrait of her mother, Madame Mama Bush (in Black and White). Her posture indicates that this is her domain, but she strains a smile, forcing her face to fold. She wishes to implicate the viewer, to catch them in the act of looking. Our gaze glides over stretches of skin and slides around the surface. We struggle to hold this image, it slips from our grip. Only she is rooted in this space. This is the fragile balance of seer and seen in Skye Volmar’s work. The figure, a vague self portrait for which the show is named, confronts us, “I see how you look at me.”

What we know love as — how we describe love — is not always what love is. Looking has never been seeing; fetishizing has never been loving. This body of work is, to my eyes, concerned with looking and loving. The work shows us what is lost when looking is conflated with surveilling, fetishizing, policing, enjoying, and certain unfortunate notions of ‘loving’. The experience of being seen and/or loved, especially as a fetishized being, is hardly ever passive. It can feel invasive. It requires our labor: that we actively assess whether or not we feel safe when held by another’s gaze. She knows even if you don’t.

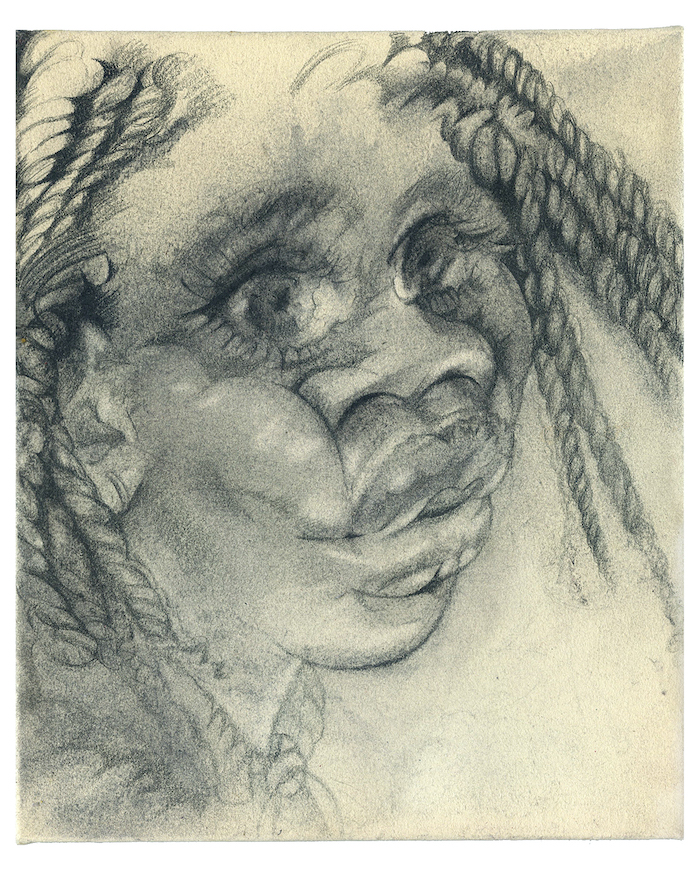

She sees us again through a swarm of dark cool purples, neutral greens, and warm browns. Here, kisses are roses climbing a fence, or petals scattered across a bare mattress. A pile of them collect around her neck. We can’t see everything in Bed of Roses, a drawing made of colored-pencil and makeup; some things are hidden from view. The image remains in a sleepy, sweet spot of confusion caught between abstraction and figuration. The ground itself is a shaky, undulating grid, almost a tessellation of floor tiles. The figure is bracing herself. Her arms held up like a shield above her head, leaving the rest of her body exposed. She sees us through one eye reverberating outward, with eyelashes in sharp fragments of flashing green. A moment of need is communicated through her fractured gaze and the distortion reveals itself as a vehicle for panic and disorientation. This eye is the epicenter of a visual language we’ve come to associate with Skye’s work, in which she fragments parts of the image while leaving the whole intact. This creates multifaceted images, moments that mean many things at once. There are too many truths for one pair of hands to hold or fend off, and far too many to see upon first glance.

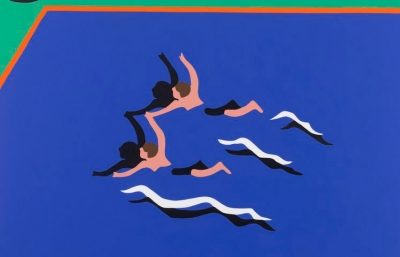

Details come in and out of focus. We find them in frizzy braids, fences and fields of flowers, between puckered lips, and cracks in concrete. Skye understands how to move and manipulate the eye. She knows when and where to provide relief. If we find and follow her gaze, she can see us through a world of overwhelming sensitivity. We find things growing in unexpected or unlikely places. These are blessings which slip from her world into ours through all the trappings of a perception that does not belong to her. They flower amidst the chaos, violence, multiplied oppression, and misconceptions regarding how people like us should be looked at, seen, and loved. A tulip bursts through concrete, standing erect before a brick wall. These bodies were not meant to struggle; that is not their nature. It is their nature to live. Yet, to live in this context, is to resist.

Written by Mary Kuan with the aid and friendship of the artist. The exhibition will be on view at Richard Heller Gallery through December 18, 2021