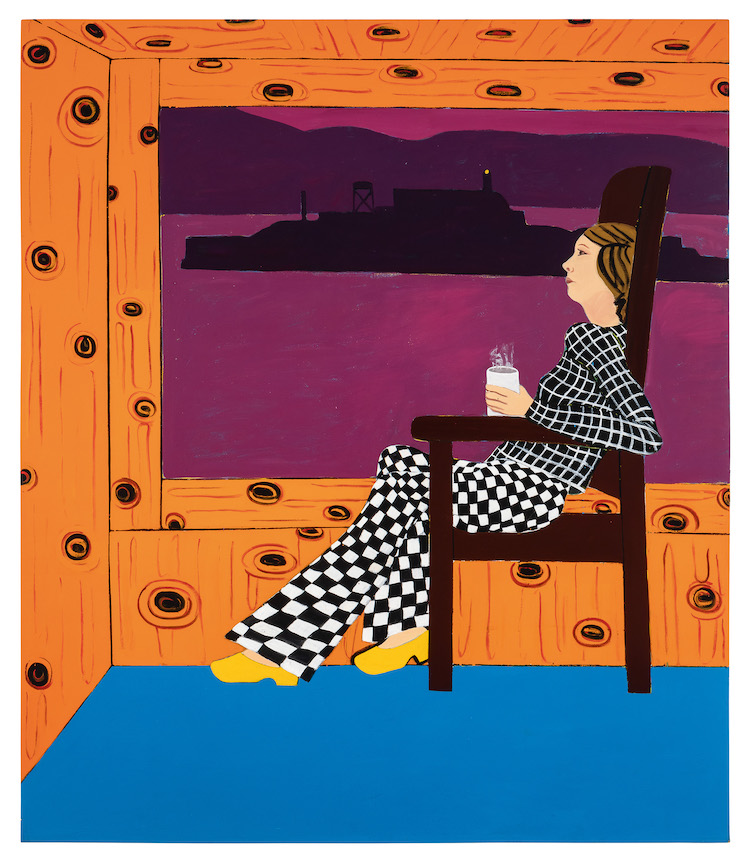

The pejorative only child, Joan Brown grew up in a dark apartment and died at age 52 while installing a mural in India when a turret above her collapsed. But in between, what a life, an artist doing what she loved at that very moment, who described blue as a “clear, joyous and contemplative color with no beginning and end.” I spoke with Janet Bishop and Nancy Lim of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art about celebrating Brown and her “irrational palette” in the current retrospective.

Gwynned Vitello: I was so intrigued with Joan Brown’s life, beginning with my surprise that she was set to go to a Catholic women’s liberal arts college before abruptly pivoting to art school.

SFMOMA: Who knows what would've happened had she not seen a flier for the California School of Fine Arts when she was seventeen years old? She certainly did not come from an artistic family.

She seemed to be“converted from the start with the freedom, as well as the mentoring of her teacher. Had she made art before?

Joan visited the local museums on her own as a youngster, and we know she drew because she submitted drawings of movie actresses as her portfolio for admission to the school. In fact, she wasn’t allowed to take painting classes during her first year and was required to take commercial design courses. She didn’t feel an aptitude for that and seriously considered leaving school. At the end of her first year, at the encouragement of another student, Bill Brown, who became her first husband, she decided to enroll in a summer class with Bischoff. That was the turning point. And yes, Edward Bishoff was unusually important to her.

Famously, what Bischoff told her was, “Trust your instincts.”

He was particularly able to cultivate these kinds of mentoring relationships with students, and his relationship with Joan went on for many years, especially when they became teaching colleagues at UC Berkeley for a number of decades.

She took her role as a teacher very seriously. I watched a panel with three former students, and I liked Hilda Robinson’s remembrance that Brown gave her a sense of freedom and the reminder that there are no boundaries when using color.

She valued so deeply her experience as a student and naturally carried it forward in her approach to being an educator, which she was for virtually her entire career. Talking about freedom, one thing that has always impressed me was her ability to absorb what was going on around her, for instance, the abstract expressionism that really dominated so much of the practice at the school. She made it her own, and among the artists of that period, she was one known to have forged a truly distinct independent vocabulary.

Did she forge any special relationships with other students at that time?

She was good friends with Jay DeFeo. They lived in the same building, known then as Painterland. In fact, they were so close they knocked a hole in the wall between the apartments so they could go back and forth.

I wouldn’t characterize her as adhering to one style, but wasn’t she advised to choose between figuration and abstraction?

In her early years she moved naturally between the two, but by 1960 or so, was pretty committed to figuration. You see the lessons of abstraction coming through in her approach to figurative painting, but what resonated was a subject matter she could connect to herself and her surrounding world. Her work has been described as a visual diary, similar to a point you made earlier.

Is that possibly why she was dismissed by some critics as not substantive?

She did paint things around her, and, yes, much of it was very gendered. She was very domestic, and a lot of scenes in the early sixties portrayed that, especially the number of paintings that focus on her son.

Well, that brings me to the Thanksgiving Turkey.

Yes! It was in her first solo exhibition at the George Street Gallery in New York, and it was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art—astonishing because she was 22 and not even out of art school. I think she was in graduate school, so her rise to success as a student and shortly after was really extraordinary.

The turkey is fascinating, both as a subject and in her rendering. Here's this woman who was practically a roommate of Jay DeFeo, a certified Beat but who is baking Christmas cookies, organizing Easter egg hunts, and then painting this turkey that would not make the cover of Bon Appetit.

On one hand, it’s a corny subject, but on the other, she’s referencing Rembrandt and his 17th-century painting of the hanging beef carcass, as well as navigating a world between abstraction and figuration. Look at the piece kind of upside down— it’s really abstract passages that coalesce into a three-dimensional object. Look at the positioning where the turkey is on the table, and there’s such spatial depth, so much perspective. It's very sophisticated, historically informed— and deeply weird.

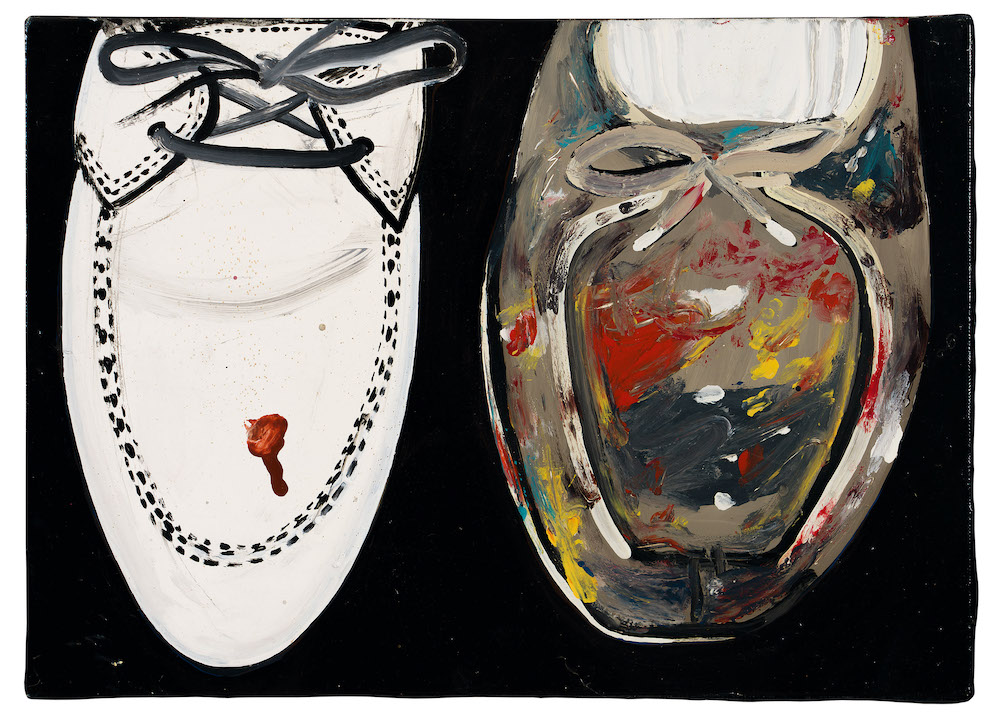

I was more familiar with her flat, personal pieces, so this painting is surprising, as is The Rat sculpture. When did she study sculpture?

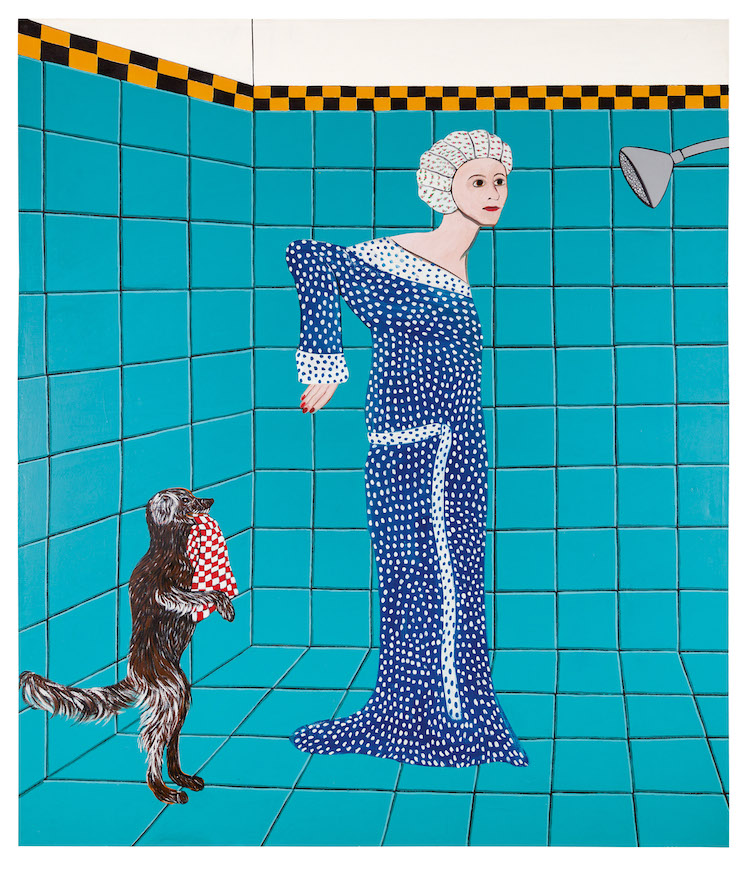

She just picked it up, making sculptures with her cohort, as well as the influence of her second husband Manuel Meri. Joan made sculptures out of whatever was around, which was the ethos of the day: use what’s around you and be scrappy. The Rat is bandages, rope and a raccoon coat she pulled out of her closet. She was also interested in Egypt at an early age, and that manifests in the piece, this reference to mummification.

She did a lot of research on her own as a girl, a lot of it at the public libraries, right?

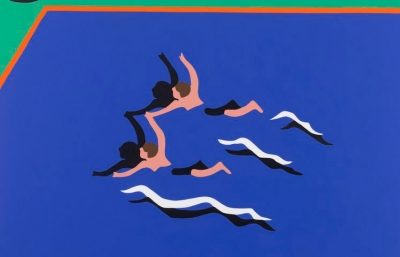

She grew up in the Marina district, right by the Bay, and adored swimming in the late afternoons and early evenings. She loved the way the sunlight hit the water.

That reminds me of her first trip to Egypt and being enthralled with the light, describing it as lavender. She never claimed to have synesthesia, but she used color in such amazing ways.

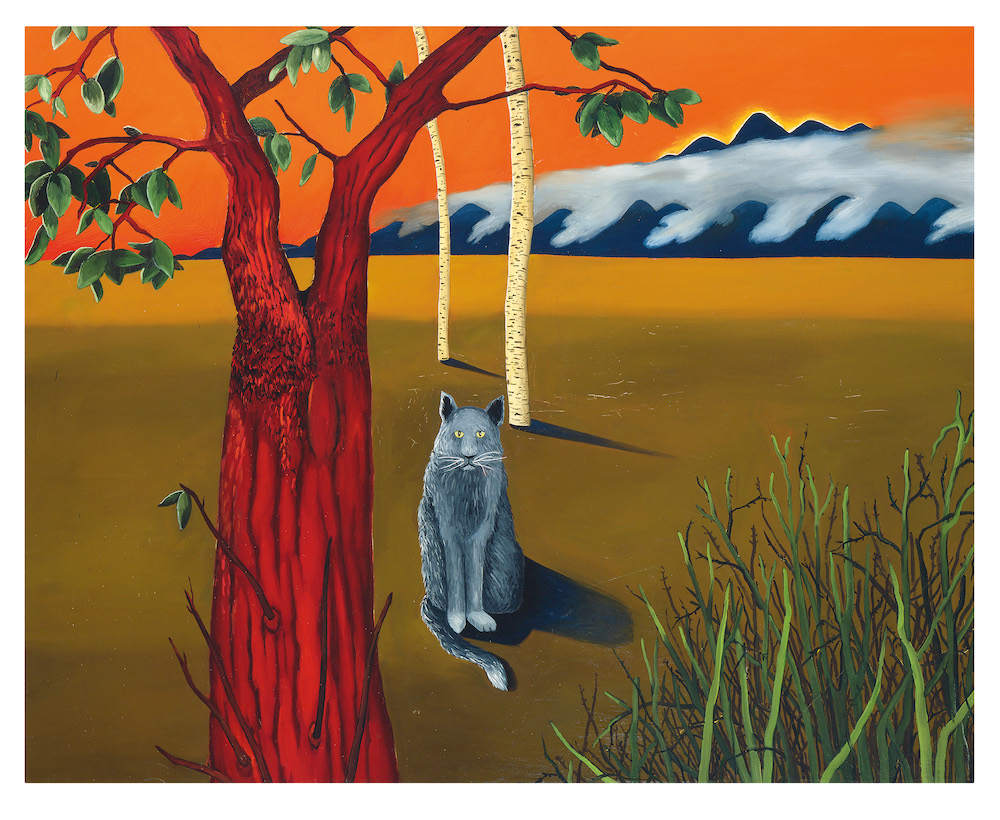

She was so drawn to color, really vibrant color, a rich saturated palette. Among the Bay Area figurative painters, I would say she is associated with the most robust handling of paint, the most thickly built up surfaces.

She achieves popular and commercial success very quickly, and then decides to sever ties with her New York agent. Maybe, as advised, she went with her instincts?

She retreated to her studio, deciding to take time off from the artworld, but continued making works at a slower pace, in a very intentional way, really setting parameters for herself. The last heavily impastoed work she made at this time was the Green Bowl.

I thought she admitted to having trouble with perspective, but doesn’t the Green Bowl refute that?

You know, the composition is similar to Thanksgiving Turkey. She acknowledges turning to this kind of shallow, straightforward division of space, which was a comfortable way to create scenes for her figurative works. She learned to create perspective in a room by looking at artists like Francis Bacon, seeking to work flatter, scaled and in simpler palettes. What’s interesting here is the vestiges of crazy colors she had been working in. There’s sparkle throughout, especially in the dark green background, a phosphorescence, and actually, the bottom is sparkly too, almost like the vestiges are leaking through, even as she tries to be constrained in how she paints. Her goal was to simplify until she understood what she wanted to do and move forward. There was a sense that needed to extend the perspective as radically as possible before getting to that really flattened space. There’s tremendous detail and the use of much smaller brushes.

I know most of her paintings are big, so was she going smaller?

She’s working with a much finer touch, but the majority are big, and I would say it’s unusual to paint so consistently large. We talked about her love of swimming, and she explored elements of physicality and kinesthesia in her big paintings. It took a lot of energy, especially given the thick paint she was applying.

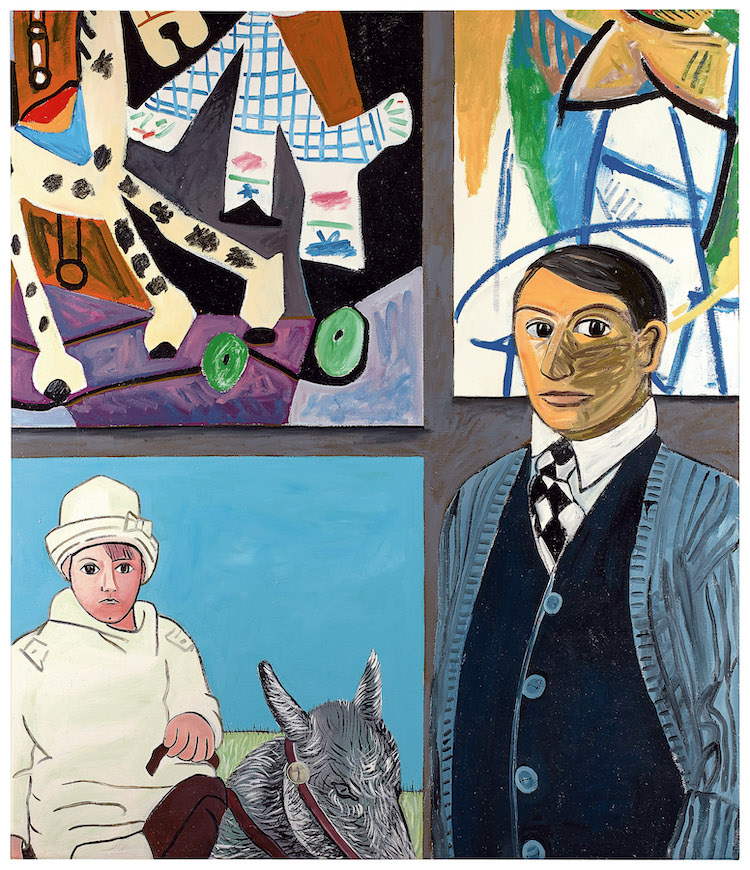

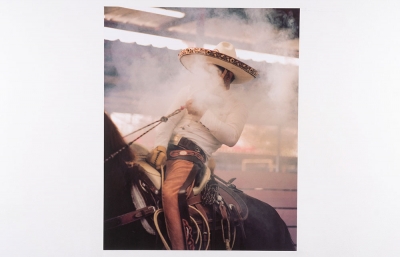

I know she collected postcards from museum shops and visited local museums on her own, but it was still kind of a shuttered childhood. How did travel influence her?

She made her first visit overseas with Manuel Neri. They visited several countries, and these were very formative experiences. Her first husband had given her a small set of art books, so she absorbed these reproductions and was very compelled by what she was seeing. When she saw them first hand, as she would say, “it really knocked me out.” She became an avid traveler and museum goer.

And an avid swimmer. I love the look of pride and enjoyment in those paintings.

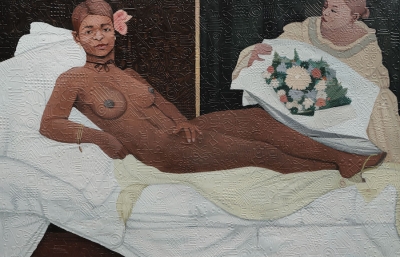

Yes, there’s a whole series of women in the water, and regarding her interest in light, she said that she was inspired by moonlight hitting the water, a quality she wanted to capture. She was always interested in transforming this immaterial light into materiality. She also takes on self portraiture in the early ’70s, and that remains her most frequent subject.

I’ve seen comparisons to Cindy Sherman, but maybe that’s simply because they are two women exploring self.

I feel Sherman is almost like an actor taking on the guise of a character, whereas Brown sometimes does but is always very present in hers. She tends to be, not expressionless, but reserved in presenting herself; there’s one where you see two heads and she's sort of showing off her new dental work. It’s unusual to see her present herself with such a highly expressive face.

One of my favorites is her posing with the fish, and “wearing” the cat head. She seemed to revel in and appreciate life in such an earthy way. She died too young, but it seemed to be a very fulfilling life. What you each discover and appreciate while putting this show together. Janet, what did you learn?

Janet Bishop: I think most enjoyable was learning the facets of her life, hearing vignettes from people we talked to. One of the pleasures of organizing this show is that her work is so narratively rich. I could use so many descriptive adjectives after hearing all the stories connected to her paintings and sculptures.

Nancy Lim: Something I came to appreciate deeply was her fearlessness and commitment to working on whatever style best suited her concepts. She was unafraid to respond to pressures around her. She was comfortable following her own path, even if friends and family didn’t feel it was the right thing to do.

Joan Brown will be on view at SFMOMA through March 12, 2023.