Accessing music digitally is practically instantaneous. Not so with vinyl, which takes a minute or two as you take the record out of its sleeve, put it on a turntable, pick up the needle and cue it to listen. Often it’s the record sleeve we connect with first. Cover art offers a clue, a sign, a portent of what is to come and, for many, an element as cherished as the music it represents. I’m part of a generation that adored this side of vinyl culture. The sleeve design would often be the first place I’d engage, looking at the images adorning the store’s walls and flicking through the contents of the record shop.

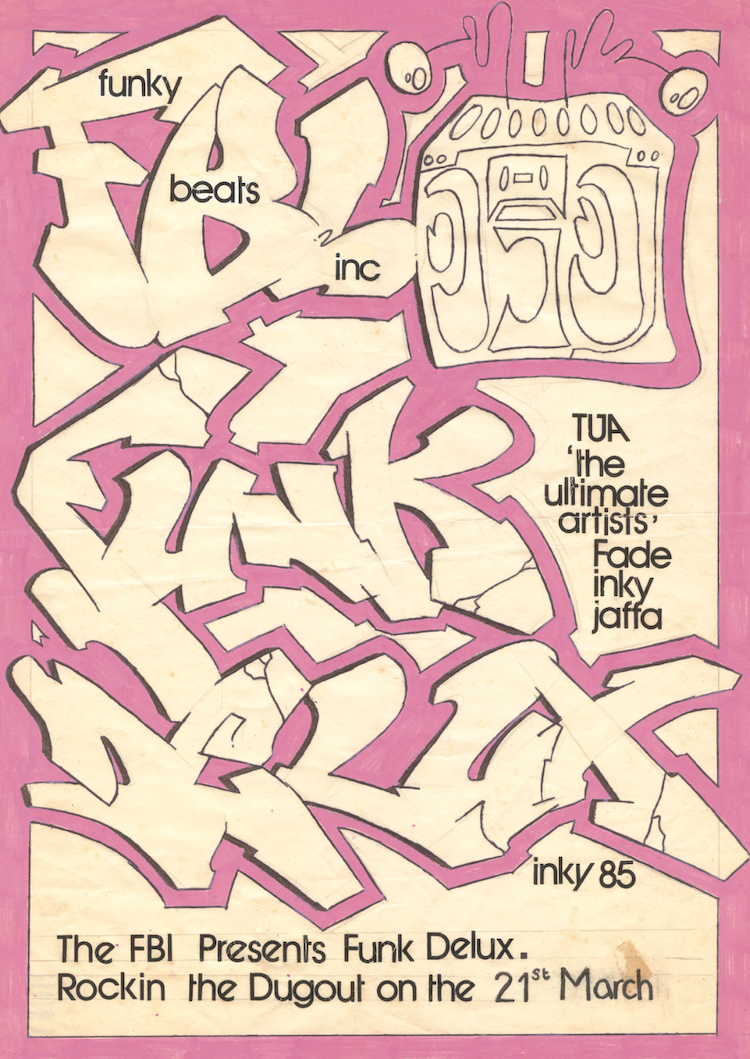

In the ’80s and ’90s, the DIY music scene in Bristol was synonymous with a home-grown visual culture. Countless flyers for music events, parties and jams would feature work by local street and graffiti-inspired artists. As the Bristol DJs, promoters and music fans from these events started releasing records, this relationship between image and sound, between visual artists and recording artists progressed symbiotically.

During the years I was running Hombré Records, I wanted the label’s sleeve art to advance the attitude, feel and flavour of our music, just like the many record sleeves, posters, flyers and graphic art that had inspired me. “I really like the cover” was the reaction I loved hearing. I was lucky enough to have a body of artist friends to go to, so when the music started to find me, creating the cover art was feasible too. Hombré ran from 1997 to 2005, but with Bristol being Bristol, it’s just one of many stories where audio meets visual.

Spending days stage diving to Bristol bands like The Seers and distracted by the emergence of rave culture, the proliferation of Bristol Sound in the late ’80s and early ’90s largely passed me by. But as a record buyer, and native of the city, I was well informed by the art on the streets and its relationships—flyers that indicated something distinctly urban, influenced by New York hip hop, was brewing. As it came to pass, this energy joined with Bristol’s existing reggae, sound system and post-punk scenes to become globally recognised. Seeing the video for Wishing on a Star and an interview on TV with Fresh 4 made me aware that producers in Bristol were doing something special. I’d heard The Wild Bunch play at a local skateboard park and started putting two and two together, plus my cousins, Sam and Benji Tonge (who promoted and DJ’d as Primetime) were really involved. Break looped, cover versions of songs I knew by the likes of SOS Band, Chaka Khan and Isaac Hayes became the norm. Diverse musical sources from dub, post punk, jazz and disco—music as well as lyrics—were being appropriated from the records and tracks, influencing the local scene. And the cover art was pretty good too! To my mind, the convergence of sound system culture, informed by the city’s Afro-Caribbean community and events like St Paul’s Carnival, the post-Pop Group work of Mark Stewart with The Maffia, Rip Rig + Panic; then Gary Clail and DJs/producers like Milo, Nelly Hooper; Flynn from Fresh 4, and the consistent presence of Rob Smith and Ray Mighty are the antecedents. I never tire of hearing Smith & Mighty’s cover of “Walk on By” or looking at the use of bold font, black and white tone and ‘Three Stripes’ logo on the sleeve (surely referencing their sound system of the same name—as well as hip hop’s obsession with Adidas?)

Once Daddy G, Smith & Mighty and seminal singer Carlton had masterminded the first Massive Attack release, and the street art that defined the Wild Bunch aesthetic had segued into Blue Lines, it was impossible not to feel immensely proud and excited that this music had turned into something truly unique on a global scale and, best of all, was being made in my home city. Totally homegrown!

A few years on, my affinity with Bristol culture was re-kindled when I started to release records under my own steam. And I knew from the outset I wanted visuals alongside the sounds. I wanted to find the right way of acknowledging the Bristol flavour in it all, whilst adding to the story. Cult genre movies, like Kung fu and Westerns were always a thing back then. Banksy’s The Mild Mild West—with its desert dry sarcasm and prominent place in Bristol’s Stokes Croft area—twinned with the Wild West (of England) and cowboy signaling of The Wild Bunch, influenced me to choose the name Hombré, that and the Elmore Leonard novel, as well as Paul Newman’s film of the same name. For anyone who knows the Bristolian / West Country way of speaking—I decided an acute accent on the ‘e’ was necessary, to avoid Bristolians pronouncing it “Hom-brurrr!” Banksy was a good friend at the time, and someone I recognised as very entrepreneurial, so I was fortunate that Riski Bizniz from One Cut was a big fan and wanted his art on the cover of their releases. Banksy would send me faxes with ideas for One Cut covers. Adorned with tongue-in-cheek comments, they would feature sharks, military vehicles, speaker-boxes and megaphones. Banksy’s ongoing spirit of generosity and instinct to support Bristol makers saw him continue to supply artwork for One Cut’s Hombré releases despite becoming better known.

This visual dimension to the Bristol scene kicked off around the time Banksy and Inkie—artists with connections to two different eras of Bristol sound, together with a community of artists who’d since made Bristol their home, organised Walls on Fire in 1998. A crew of graf writers/DJs/MCs and Producers—Fantastic Super Heroes—who went on to evolve into Hombré’s most notorious hip hop act, Aspects, were omnipresent at that time, and helped provide Walls on Fire—the event—with its soundtrack. Bristol Polytechnic’s fine art department, based at Bower Ashton and soon renamed UWE, was instrumental in bringing street artists and illustrators like Dicy, Feek, Will Barras, Mr. Jago and others to the city. They, in turn, got things going for artists they knew from the North and the Midlands who subsequently made Bristol their home—such as Paris, Xenz, Eko (Twentieth Century Frescoes)—and ensured regular city visits from mavericks like Chu and The Toasters. Once this Bower Ashton scene and the older Bristol street artists had come together at the Walls on Fire, Bristol’s street art offer had begun a new chapter, one that would garner a global reputation.

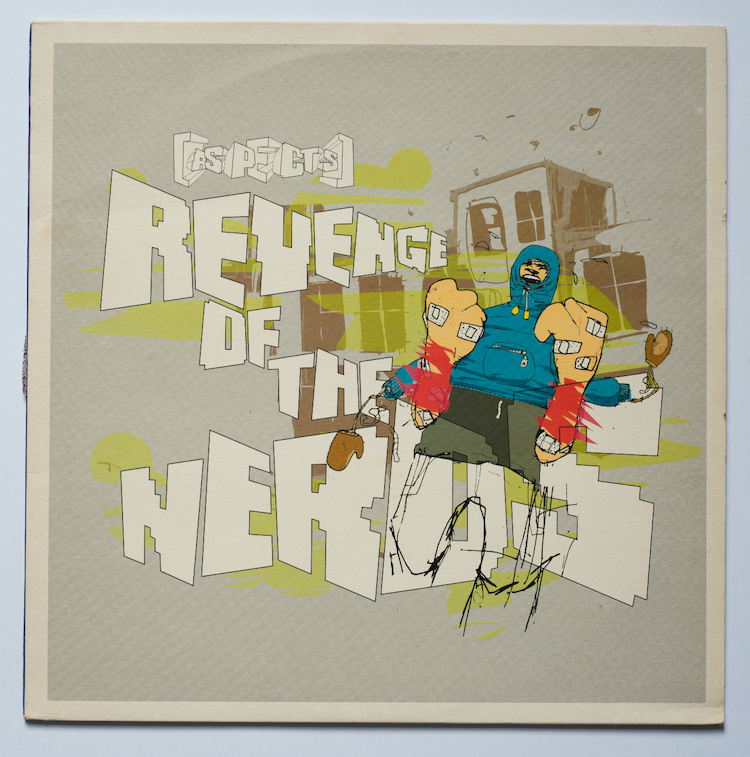

Not long after, Hombré experienced the phenomenon of making a hit record in the shape of Aspects’ Correct English LP. With amazing visuals from TCF’s Eko, who supplied the sleeve art, the work epitomised the ethos of the time. Featuring MCs hailing from Somerset and further down the South West, Aspects possessed a rural element that mixed Bristol’s urban scene to develop something different to that ’90s Bristol Sound, something unquestionably “West Country.”

Being true to where you’re from, as well as where you’re at, is unashamedly Bristolian and a key part of Aspect’s success. Roni Size gave a great interview, describing the journey between London and Bristol as one in which plenty of reflection, thinking and decision-making gets done. Clearly, it’s a road regularly travelled by Bristol culture makers, but he made it clear that he didn’t see any creative need to be based in London. 3PM and Tricky Kid, then later Turroe, Undivided Attention, Retna, Reds (One Cut), Rola (Numskullz), Dynamite MC, and Aspects rapping in their Bristol accents; 3D, Inkie, Nick Walker and later Banksy were paying tribute to the West Country in their art. Such milestones and signifiers of being true to where you’re from and what (and who) influenced you, are all part of the Bristol approach.

Bristol’s street art may well derive from the city’s historic association to cut and paste sampling and hip hop shot through with carnival sound system culture, but time makes it evident that those settling in the city can assert real influence too, here and everywhere.

Bristol is a city that breathes culture, nurturing a fertile environment for innovative expression, industry, and fierce independence, all stirred into a relentless melting pot. From the slave trading shame that formed its economy, to the statue-toppling dismantling of an ideology that does not serve its people, Bristolians assemble and share ideas often spearheaded by sound and vision. Enabled by the cultural inter-play, resulting first in ripples, then full scale waves of industrialising and innovative output, from one Vanguard to the next. Ad infinitum. —Jamie Hombré

This article is published in conjunction with Vanguard | Bristol Street Art on view at the Bristol Art Museum in the UK from June 26–October 31, 2021.