Over the last 10 years, the artists who have evolved from street art practices have become a force in generating awareness and support for global issues. Beyond the central-casting image of activist “leftie,” they make works as innovative as they are engaging. Where some promote a call to action, others seek to illuminate the growing disparity in our understanding of visible and invisible threats.

This is a great opportunity to speak to an artist who advocates the dire need to understand our lack of understanding. You might not be familiar with his background in environmental protests, or his 15 years of street and contemporary art projects, but you likely have seen some of his award winning, network-based interventions, which include the digital manipulation of people such as Mark Zuckerberg, Donald Trump and Kim Kardashian via social media.

Meet Barnaby Francis, better known by his pseudonym, Bill Posters. Activist, artist and author, Posters investigates and exposes the armor of corporate control, revealing the imposed obfuscation of truth through his elegant art interventions. By shining a spotlight on the invisible forces designed to influence us, he questions how vulnerable our collective and individual identities have become in the age of surveillance capitalism.

Charlotte Pyatt: There is some pretty heavy, cross-disciplinary theory that drives the development of your work. What got you started down this path?

Bill Posters: I am interested in art as critical practice and believe there is a responsibility to understand whatever it is you want to critique. I read a lot of dry academic reports, arts, sciences and advocacy theory—often multiple times, as they are so inaccessible—then I attempt to distill these complex ideas and try to bring others into the process. There is a long history of street art and hip hop culture taking DIY approaches, and I really started to understand more meaningful processes when it became about DIT—Doing it Together.

As for the start, I guess it came while at university in Liverpool around 2002. Myself and my crew EP (Extended Play) were raided by the British Transport Police for painting trains. I narrowly missed being arrested, but in order to protect myself, I had to destroy everything. My whole identity and persona as a writer had to be completely erased—sketchbooks, laptop, hard drives, rail worker uniforms. This moment coincided with a shocking global event, the illegal “for profit” Iraq war unfolded against the wishes of the wider international community. Operation Shock and Awe started a cataclysmic series of events that the world is still adjusting to today.

This self-censorship, together with the impact of the raid on my friends (some of whom got suspended jail sentences) was devastating. Where the police raid reframed my purpose, the Iraq war reframed my politics. It made me fundamentally question my relationship with creating art in public space.

This is how you came to be involved in “Subvertising?” Can you explain the objectives of this practice?

I got deeply involved in political activism in the early “naughties,” organizing collective forms of direct action against fossil fuel infrastructures in the UK, like power plants, fracking sites and airports. I started collaborating with other artists passionate about affecting change in public space.

Subvertising is a form of street art which seeks to challenge outdoor advertising and the power that advertising has in our culture. We targeted privately owned ad spaces in the city and replaced posters promoting commodity exchange with anonymous art by some of the world’s leading street artists, designers and illustrators. We used their ad spaces as a lens to look back at them.

Why make the interrogation of advertising a priority, and what did you hope to achieve?

If we want to understand the messages that define popular culture, then we have to look at the primary storytellers. In our culture, the storytellers are the ones with the most money—the advertisers. Public space should be an arena in which no single authority should reign. Multiple voices should have the freedom to be heard, and this principle is at the core of the street art movement. Advertising dominates our shared environments, both physical and digital. When you begin to understand capitalism, you see advertising as the visible engine that drives consumerism. I wanted to take the power of advertising, learn how to hack it, and interrogate the intersectional issues that capitalism exacerbates. To do Subvertising interventions at scale, I co-founded the Brandalism project in 2012. We work with artists around the world to collectively install hundreds of pieces of Subvertising in cities. To disrupt the story that capitalism tells in the city—to create a glimpse of something different entirely.

How do you ensure the integrity of the message over the sensational aspect of the action?

The Brandalism projects creates interventions at key media and political moments to ensure maximum impact. We wanted to create the world’s largest unauthorized exhibitions in public spaces. One of our most meaningful interventions was for the COP21 Climate Talks in Paris, 2015.

For 8 weeks, we worked with over 100 people in Paris and 80 artists from around the world for a large-scale action the day before the climate talks began. Our aim was to make visible the links between advertising, consumerism, corporate lobbying and climate change, at a key global media and political moment. This “media sculpture” would attempt to hijack the media narrative away from the corporate lobbyists and the greenwashing sponsors of the climate talks. Our network of Subvertisers installed over 600 pieces of art in a day across the city center of Paris, even after an armed raid by police on our workshop, receiving global press coverage in the process. It was the most intense experience of my life.

There is an emphasis on the language you use to talk about your methods and your practice. Words like invasion and interrogation infringement, territory. Is this intentional?

It’s all very conscious for me. I value the journalistic process, the investigation and interrogation of facts and issues. This critical research underpins the process of trying to give materiality to those enquiries or logics.

Over the last few years, your practice has migrated from public to digital space. Why the transition from the streets to digital spaces?

In 2017, after a decade or so, I felt like I had reached the limit of how far I could engage with Subvertising. I like the saying, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” and with Subvertising, you are always creating and intervening within the limits of a material space. Corporate power manifests in ad spaces to create what academics call a persuasion architecture, and you can also find these persuasion architectures in digital space. However, they are invisible and hidden by the “black box” technologies of the digital influence industry. To paraphrase German philosopher Byung-Chul Han, wherever power does not come into view at all, it exists without question. So, the greater the power is, the more quietly it works. I wanted to interrogate the new powers of what we now call surveillance capitalism.

In Summer, 2019, Spectre ignited a global conversation concerning misinformation, data, privacy and democracy in digital spaces. Tell us, what is Spectre?

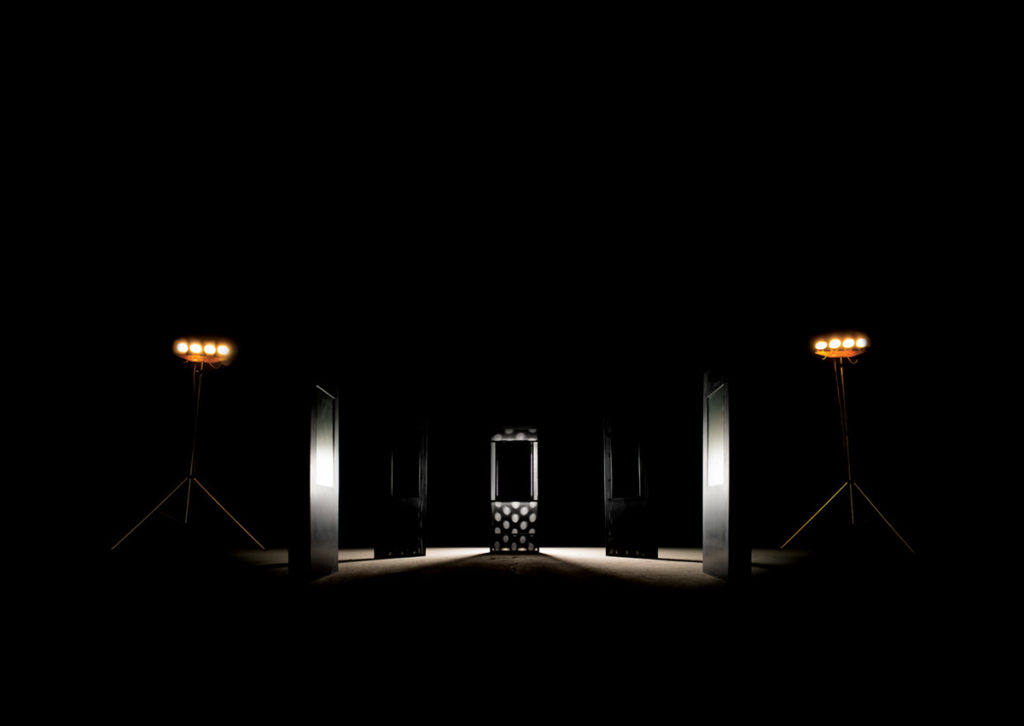

Spectre is an immersive new media installation created with US artist Daniel Howe and named after the online persona of Dr. Aleksandr Kogan, the data scientist that sold 87 million Facebook profiles to Cambridge Analytica in 2018.

Spectre started out to subvert the power of the Digital Influence Industry, and, via a series of viral deep fake artworks, it became embroiled in a deeper, global conversation about the power of computational forms of propaganda, leading to unexpected—and contradictory—official responses from Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

The installation is presented sculpturally as a stone circle for the twenty-first century, inviting users to explore the deeper ethical and moral implications of surveillance capitalism on privacy, trust, truth and democracy. The experience is curated by algorithms and powered by visitors’ personal data. Spectre interrogates new forms of computational propaganda including OCEAN (Psychometric) profiling; gamification; “dark design”’; “deep fake” technologies; and micro-targeted advertising via a “dark ad” generator.

The installation was heading to SXSW this year after we won an artist commission to engage audiences in the lead-up to the US 2020 elections. Unfortunately, SXSW was cancelled, so we are currently looking for new touring partners for later this year.

Where did the idea for deep fake based works come from?

Porn. Deep fakes are a powerful form of synthesized video, over 90% of which are currently used for misogynistic, non-consensual celebrity porn. We wanted to use the same technology in a creative way, to synthesise celebrity identities in a conceptual way. A critical part of the interrogation was about addressing whether people should be able to use the biometric data of others. And, if not, what are the social media platforms doing—if anything—to mitigate potential harm on their platforms? This is why we released a series of the deep fake new media works as a digital intervention on Instagram, to troll Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook’s lack of policies.

How did these new technologies move you beyond the limitations you were experiencing on the streets with Subvertising?

These new technologies and territories allowed a shift from hacking corporate power in 2D (like Subvertising) to exploring computational forms of propaganda in more conceptual ways. The digital influence industry is incredibly powerful and opaque by design, so we must challenge the new technologies of power that are so present in our lives today. In relation to deep fake technologies, people feel emotionally connected to celebrities, and they have cultural power that we wanted to subvert. These new media works allow the exploration of pressing “truths” in very relational and provocative ways. I also think that deep fakes are the perfect art form for our absurdist reality. Trump is the President of the US; disinformation is enabled at scale online for profit; constant economic growth with finite resources; neocolonialism; climate change; and now a global pandemic. Life is becoming totally absurd.

Is there an ethical dilemma in manipulating the likeness of people for the vehicle of your messaging?

Yes, there is. My work is about raising awareness of human rights and critically interrogating power relations between corporations, governments, people and the artist. With deep fakes, you are operating ethically in a difficult space. There are insufficient laws in place to appropriately protect people’s personal data. Even after the viral circulation of the Zuckerberg video, there are still no protections to prevent me or anyone using the personal data of others. So I justify using the form of deep fakes as a window to explore systemic issues. The more people can be made aware of the dangers to our privacy and the ways powerful technologies can use our personal data in unexpected ways, the more informed and protected we can be in our relationships with new forms of totalitarian power.

What is the fundamental take-home from your work?

My practice inhabits the border between art and propaganda, and I think as the forms of art I’ve been expanding into have developed, my intentions have become more conceptual. That said, we need to be aware of how power operates today, and be critical of new emerging technologies of power and hierarchies of knowledge. In the digital space, the “Big 5” tech giants are now essentially ultra-nation-states, operating across borders and above legal jurisdictions. For capitalism to survive on a planet of finite resources, it always needs new territories to expand into, and right now, your behavioral data— your psyche—is the new territory. Ripe for exploitation, extractivism and enslavement-through-dependency.

What’s coming up for you?

My company, Big Dada, is working on some projects in TV, music and advocacy spaces that are applying new technologies to moving image storytelling. I’ve just co-produced a music video for Lil Uzi Vert’s track “Whassup” on Atlantic Records, the video is released next week. This is the first hip hop music video to be produced using deep fake tech so we can’t wait to see how it is received.

I also have a new book out with Lawrence King but the US release date has been delayed now until September 3, 2020. The Street Art Manual: A Guide to Hacking the City is a reflection of 15 years of creating critical art in public space. The book is the world’s first comprehensive street art manual. It covers 11 forms of art in public space including the socio-political histories of each, alongside practical advice, theory and guidance for creating art in public spaces around the world. It’s my small attempt to reconnect street art to it’s anti-consumerist and anti-capitalist roots.

http://billposters.ch/