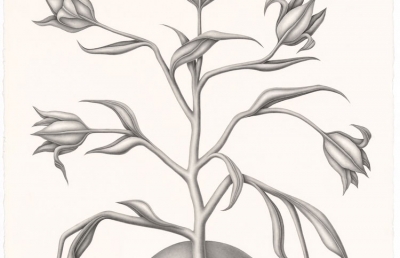

Lorien Stern’s ceramic practice began as an exercise to deal with death, but you wouldn’t know it from her works’ bright, electric hues. The Mojave Desert-based artist often remarks that she wants to make people happy through her work, creating silly sharks, friendly ghosts, goofy snakes, or other quirky animals typically perceived as dangerous or scary. For her solo show at Hashimoto Contemporary, Stern has created a cast of “Old Friends”: dinosaurs and other plants and animals from prehistoric times in her signature style. Stern talks about her love of ceramics, being inspired by prehistory, and how she hopes to overcome her own fears and inspire bravery in others.

Katherine Hamilton (KH): For your solo show at Hashimoto Contemporary SF, Old Friends, you’ve created ceramic versions of prehistoric plants and animals to connect with things that no longer exist. What was on your mind when you started this series of works?

Lorien Stern (LS): I was inspired by the great lengths of research paleontologists and paleo artists accomplished to reimagine these magnificent creatures, and I am in constant awe of what they have been able to uncover and share with the world. Although I am still a complete amateur in this field, I love watching documentaries about prehistoric life, and early paleo art is my current favorite genre of art to view.

KH: Was there a personal connection to the work?

LS: Growing up, I would visit my dad’s side of the family in New York every year. They would ask me what I wanted to do, and on every trip, I requested to go to the Museum of Natural History. I felt so much joy and wonder when I would walk around the prehistoric exhibitions—that was a massive inspiration for this show. Looking at dinosaurs feels like seeing the bodies of an alien species from another planet. It’s so exciting, and I like to make works that evoke feelings of happiness and perhaps reconnect people to childhood happiness, so this topic felt fitting.

KH: I want to talk a bit about your medium. Working with ceramics has so many challenges—you don’t always know what will come out of the kiln! But what are some things you love about the medium? Why have ceramics stuck with you for so long?

LS: This is true! I love that ceramics challenge me and help me see things through from start to finish. It’s difficult to start a sculpture and return to it later because clay needs to stay wet while sculpting. With the super dry climate out here [in the Mojave Desert], I have to try to finish pieces in a timely manner to prevent cracking. The uncertainty also helps with the practice of “letting go.” There are so many opportunities for the glaze or color not to come out, the work to crack, or even break in transit. Ceramics are vulnerable through every step of the process. I’ve spent over 100 hours on a piece that would crack during the last stage. On the other hand, when I open the kiln and things turn out well, it’s a great feeling of relief and excitement.

KH: Working with clay and being in the Mojave Desert, where ancient forces have molded the landscape, is there a specific relationship between clay—this matter that holds so much geological history—and the subject of the show?

LS: It is kind of a trip to think about the clay as something that actually helped naturally preserve a lot of dinosaur fossils. Many areas around here don’t have much modern human development, although a lot has changed geologically. Huge mountain ranges signify insane tectonic activity, and some fun rock formations appeared from ancient volcano eruptions. I like to visit these pinnacles nearby that are almost 150 feet tall that were formed when the area was underwater. It’s so fascinating how much the landscape can change over long periods.

KH: Do you remember the first time you learned about dinosaurs? What about them caused a sense of magic or intrigue?

LS: I honestly don’t remember learning about prehistoric life in school, nor do I know a lot about it, still. My earliest memory would be walking around the NYC Museum of Natural History and seeing the skeleton reconstructions of the long-necked dinosaurs and the tyrannosaurus. The mystery of seeing only the bones was a big part of the intrigue and enchantment. Their enormous size was captivating, and it was magical to encounter a creature that no longer existed. I still feel the same sentiment today when seeing paleoart or watching documentaries on prehistory.

KH: Your work often attempts to make something alien, familiar; something scary, approachable; something sad or daunting, silly. In this show, we see dinos with razor-sharp teeth in fun colors or apex predators with funny looks on their faces. Joy and wonder are central to this work’s presentation, but I can’t help but read an element of grief: these are “old friends” who have gone extinct, friends we will never know. Is there an aspect of mourning or even heartache in this show?

LS: Sure. There is an interesting need to honor and understand things that no longer exist. I realize these works may tie into other underlying themes in my work—not only the animal element but also my dad, who passed away when I was a kid. I often make work that ties to him through personal symbols as a way to have a connection to the past.

It is rattling to think about species that have gone extinct because these creatures once inhabited the same planet we live on. All species, past and present, have cultivated life on Earth, which is an incredible connection.

KH: Do you still grapple with death in your ceramics?

LS: I think death will always be an underlying theme in a lot of my work, at times in an obvious way, other times not. My practice has helped me process my dad’s passing and inspires/puts perspective on almost everything I do. Death is probably my biggest fear, and I find peace in accepting it as a part of life. Sometimes to find joy, you have to take scary risks and remind yourself, “Well, I am going to die one day,” which can help give you the little push you need.

KH: Your impulse to disarm something frightening also helps us, the audience, build empathy with the subject—maybe sharks or dinosaurs aren’t trying to scare us; maybe they’re silly and goofy too. Why do you want to make uncomfortable things comfortable?

LS: Over the years, it became important to me to choose subject matter that made me feel happy, which is strange because I am often the most fascinated by things that scare me. One of the origins of this practice might be when I made my first shark sculpture because I misunderstood an in-class assignment. My instructor asked everyone to “make a 6 inch sphere,” but I thought he said “a 6 inch FEAR.” I made a walking shark because I always thought it would be so freaky if sharks and whales could walk upright onto land just as easily as we could swim in the ocean. I really enjoyed making it, and that led to a claymation, which led to hundreds of shark sculptures. I enjoyed making the sharks in bright colors with goofy expressions while learning about the species and how misunderstood they are. Doing work like this helps me process my own fears, and I’ve learned that some people also relate to this.

KH: You’ve talked publicly about wanting to make work that makes people happy. Can you describe where or when you are happiest or feeling your best?

LS: Probably when hanging out with my pets, seeing animals in nature, and eating delicious food with friends and family.

KH If you were a reincarnation of a prehistoric plant or animal, which one would you be?

LS: Probably a long neck dinosaur

KH: Would you rather: have to live with T-Rex arms or Stegosaurus spikes?

LS: Definitely stegosaurus spikes

KH: Finally, which dinosaur would make the best friend?

LS: The Smilodon has the biggest smile and would be a very cool friend, but the longneck is probably the sweetest.

Lorien Stern’s solo show Old Friends is on view at Hashimoto Contemporary San Francisco from August 26th - September 23rd.