In the late seventies, John Divola came across an abandoned property on Zuma Beach in Southern California. The building was repeatedly burned and damaged in various ways by the fire department who used it for training exercises and practice drills. Over the course of a year, Divola returned on numerous occasions to photograph the site, making additions to the interior with paint and graffiti, augmented by others’ vandalism, decay from natural elements, and the passage of time.

Divola describes Zuma Series (1977-1978), as “a product of [his] involvement with an evolving situation…my acts, my painting, my photographing, my considering, are part of, not separate from, this process of evolution and change.” His willingness to physically intervene with his surroundings, combined with his bold use of color, marked Divola’s departure from the status quo in an era that prized the neutrality of predominantly black and white documentary photography.

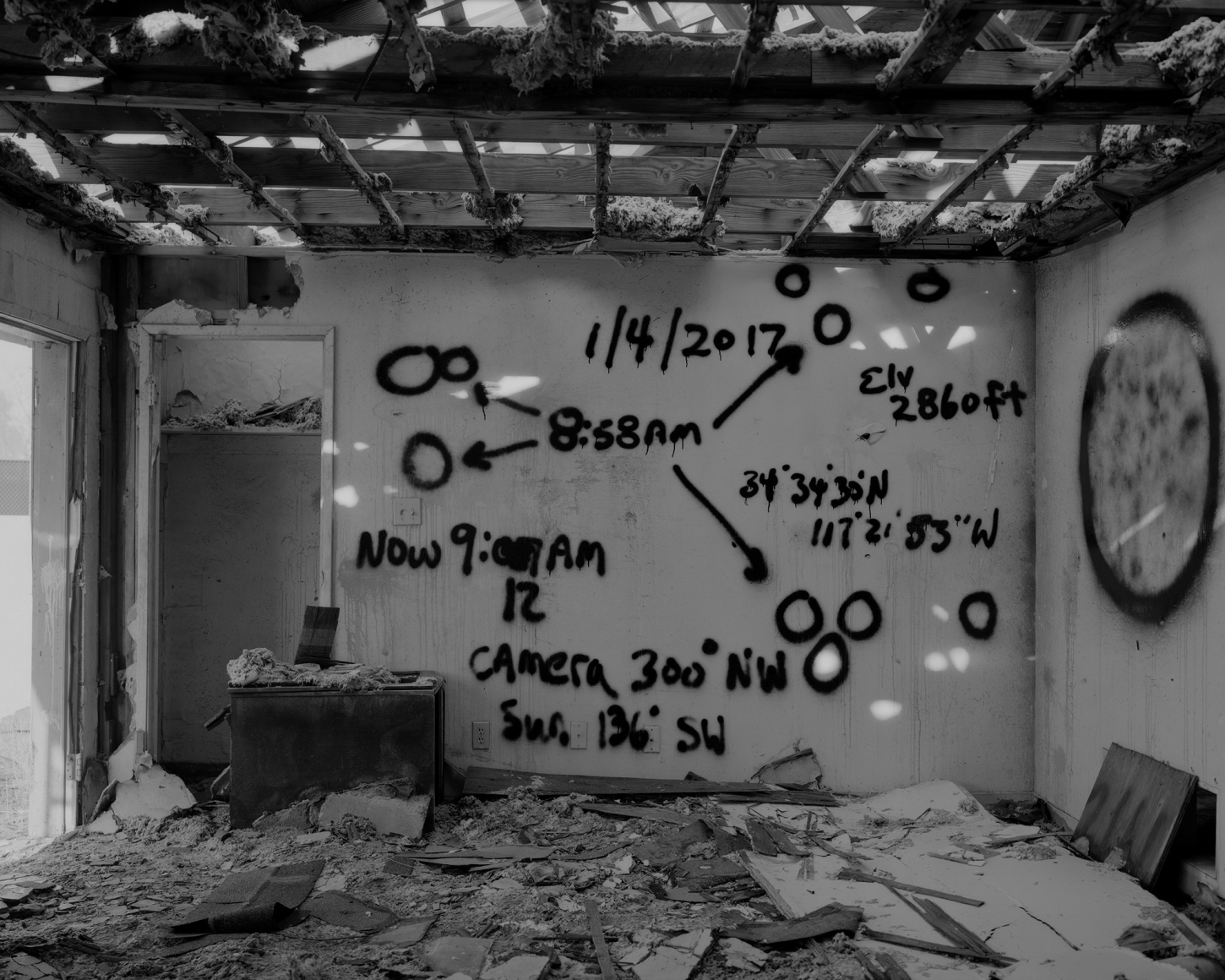

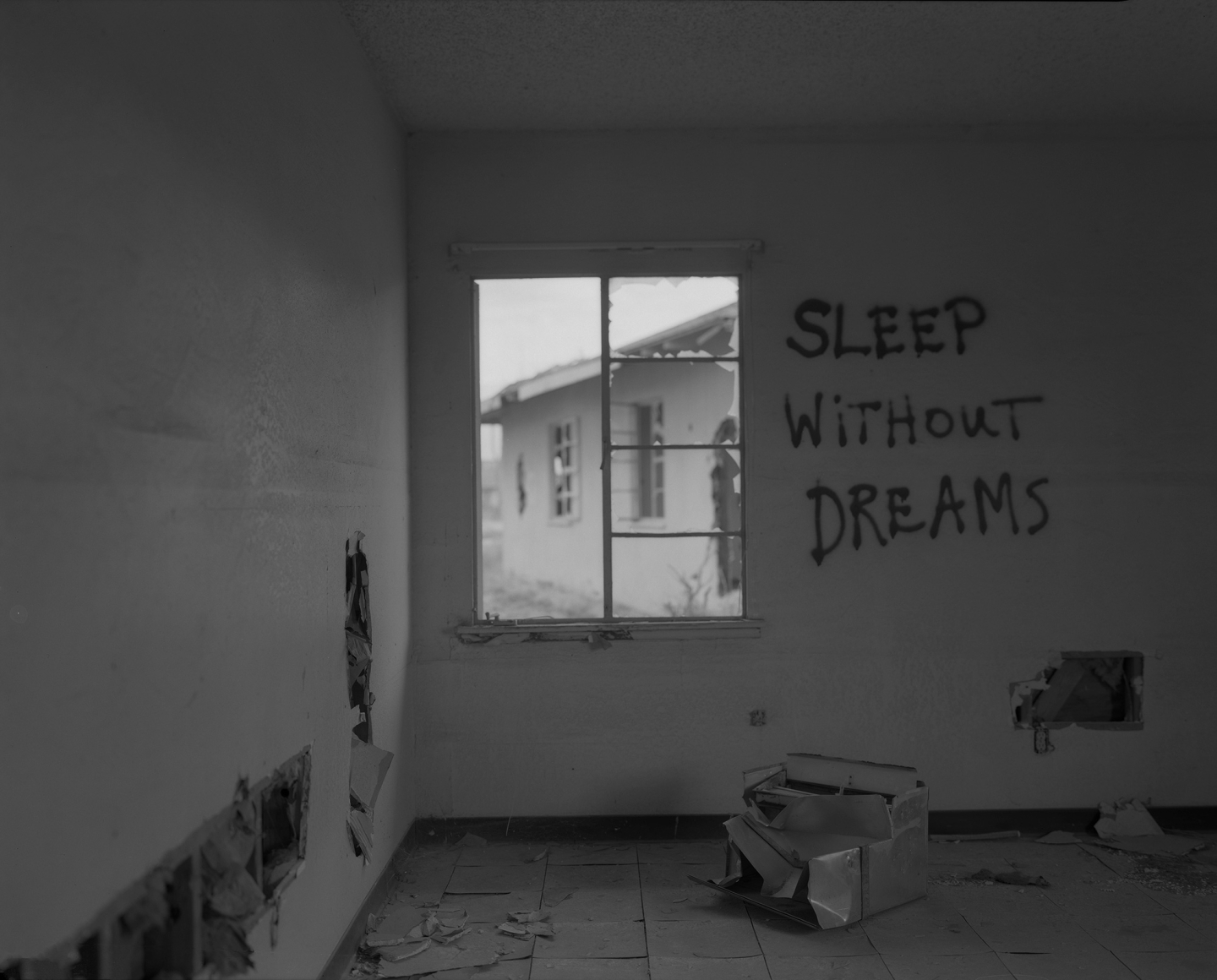

Daybreak (2015-2020) is a result of Divola’s long-term engagement with the abandoned housing complex at the decommissioned George Air Force Base in Victorville, California. In this series, Divola explores the way in which light illuminated the space, photographing primarily at dawn. By adopting the analog format of 8x10 silver gelatin contact prints for the series, Divola calls attention to the photographs as physical manifestations of his engagement in the site. Indeed, as the artist has said, “each photograph represents an index of multiple gestures. The design of the architect, the labor of the builders, the traces of past occupants… [Divola’s] own painting and installations, and ultimately [his] gestures of selection.” And it is from this multiplicity of meaning that the photographs derive their power, resisting easy categorization or interpretation as Divola embraces “the messy complexity” of photography.

Both series, which are on display at Yancey Richardson Gallery as part of the exhibition Swimming Drunk, are a result of Divola’s engagement with abandoned buildings, and his interest in transforming a situation through photography. Thus, the photographs do not serve as mere descriptions of the scenes depicted but instead are offered as artifacts from the artist’s physical and experiential interventions within these environments.