American photographer Shane Lavalette's latest project, Still (Noon), is a photographic journey across Switzerland and meditation on history and the transformative power of time. Invited to participate in a group exhibition titled Unfamiliar Familiarities. Outside Views on Switzerland, Lavalette dove into the archives of Swiss photographer Theo Frey (1908-1997), uncovering unexpected connections with his own work and ultimately using a 1939 journey of Frey's as a starting point for his project. Traveling to the same twelve villages that Frey did, he found himself reflecting on the constantly evolving meaning of photographs. “I considered the ways in which Frey's photographs have different implications now than the day that they were made,” Lavalette explains, “and how the meaning of my own images will undoubtedly transform with age as well. Photographs, I realized, are much like mountains. Though we think of images as fixed and still, what we see in them is always shifting, however slowly, with time.”

The work from Still (Noon) will be on display in an exhibition at Robert Morat Galerie in Berlin opening July 13th, 2019. A book of the same name is available to order via Edition Patrick Frey.

Alex Nicholson: Had you spent any time in Switzerland prior to working on this project? I'm curious because I know, with One Sun, One Shadow, you hadn't traveled in the south much and used your knowledge of music as an entry point. And with Still (Noon) you were able to find Swiss photojournalist Theo Frey's work and use that as an entry point.

Shane Lavalette: Both of these projects began as museum commissions. In the case of One, Sun, One Shadow I was invited by the High Museum of Art in Atlanta to make a series of photographs in the American South. For Still (Noon), I was asked to create a new body of work in Switzerland for a project that would be exhibited and published by Fotostiftung Schweiz in collaboration with Musee de l'Elysee. Peter Pfrunder, director at the Swiss Foundation, was instrumental in introducing me to the work of Theo Frey, a Swiss photographer who documented the country in the 1930s. The foundation holds his entire estate, comprising of about 100,000 negatives and hundreds of prints.

When starting a new project, especially something location-based, what do you look for before starting to take photographs? Does research come first or is it something that reveals itself once you began shooting?

Research is an important part of my process, but leaving room to exploration and chance is always of equal or greater value. For both of these projects there was a loose framework in place in terms of locations or subjects, but also room to get lost, take wrong turns, make discoveries, etc. I think that uncertainty combined with an openness to possibility is important to the creative process. A lot may be revealed while making, but the connections between images usually become clear in the editing phase.

You mention being "confronted with the weight of history" while working in the archive at the Fotostiftung Schweiz. Can you expand a little more on that understanding of your photographs aging with time? Is what they will look like in 10, 20, or 50 years something you consider when taking photographs?

I ruminate about this a lot. We're living in such an image-saturated world... How many of the images we see today will matter in 10, 20, or 50 years, as you said? How about 100 or 1,000? Not to mention tomorrow? I don't have the answer to that in terms of my own work, but I love photography's relationship with time—and I love thinking about how images change over time. While perhaps not overt, these concerns are inherent in Still (Noon).

When visiting these villages did you have conversations with people about Frey's work and your project? Did the inhabitant's own perception of their history and memory of place influence the project at all?

Yes, talking about the fact that I was essentially following in the footsteps of a photographer who had visited to document their village eighty years ago was often an interesting starting point for a conversation with a stranger. These conversations gave me some insight into how these villages had changed since then (or haven't much at all). In many cases, the villages are like stepping back in time and these conversations made me feel that as well, which I'm sure seeped into the image-making.

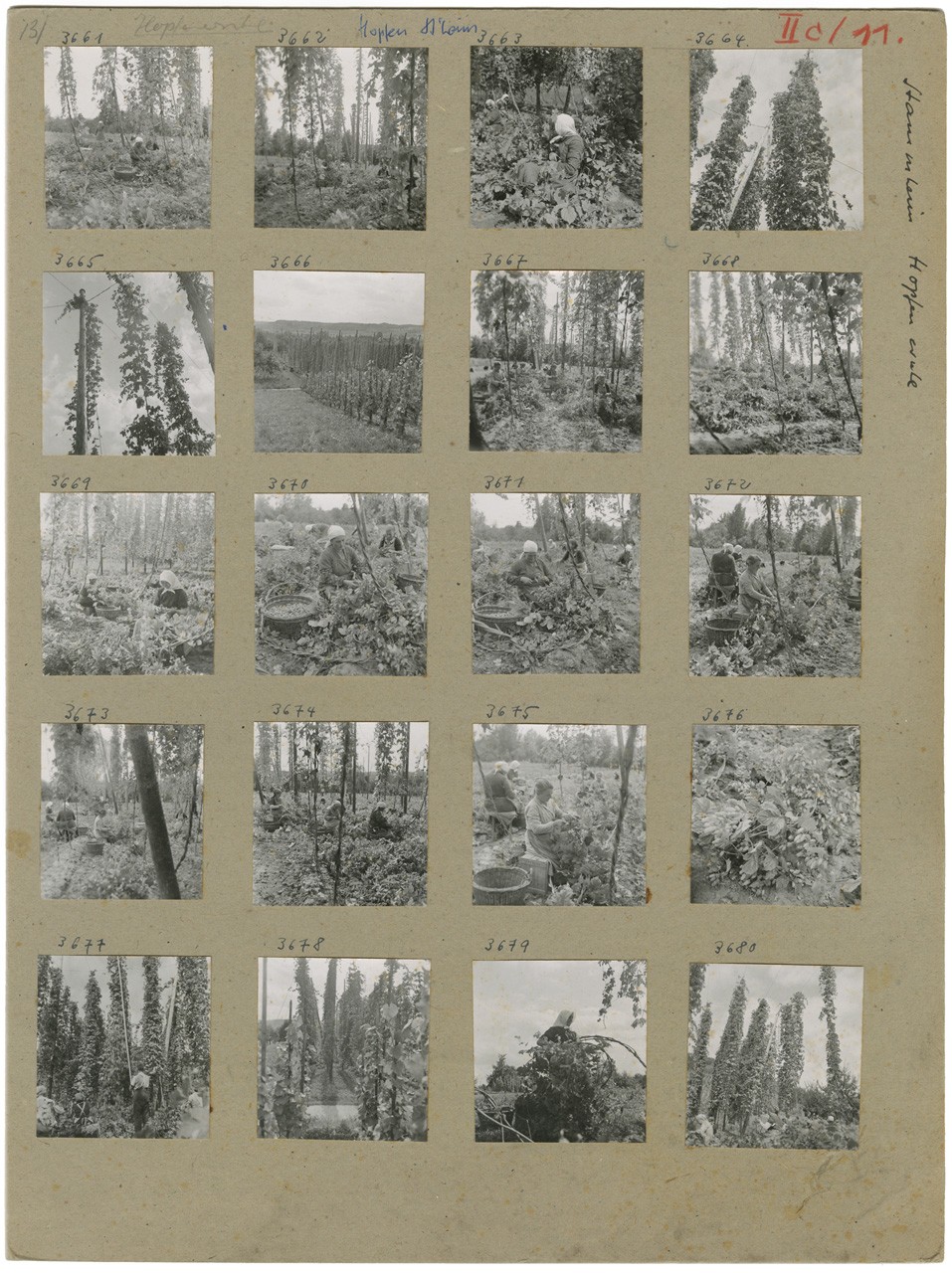

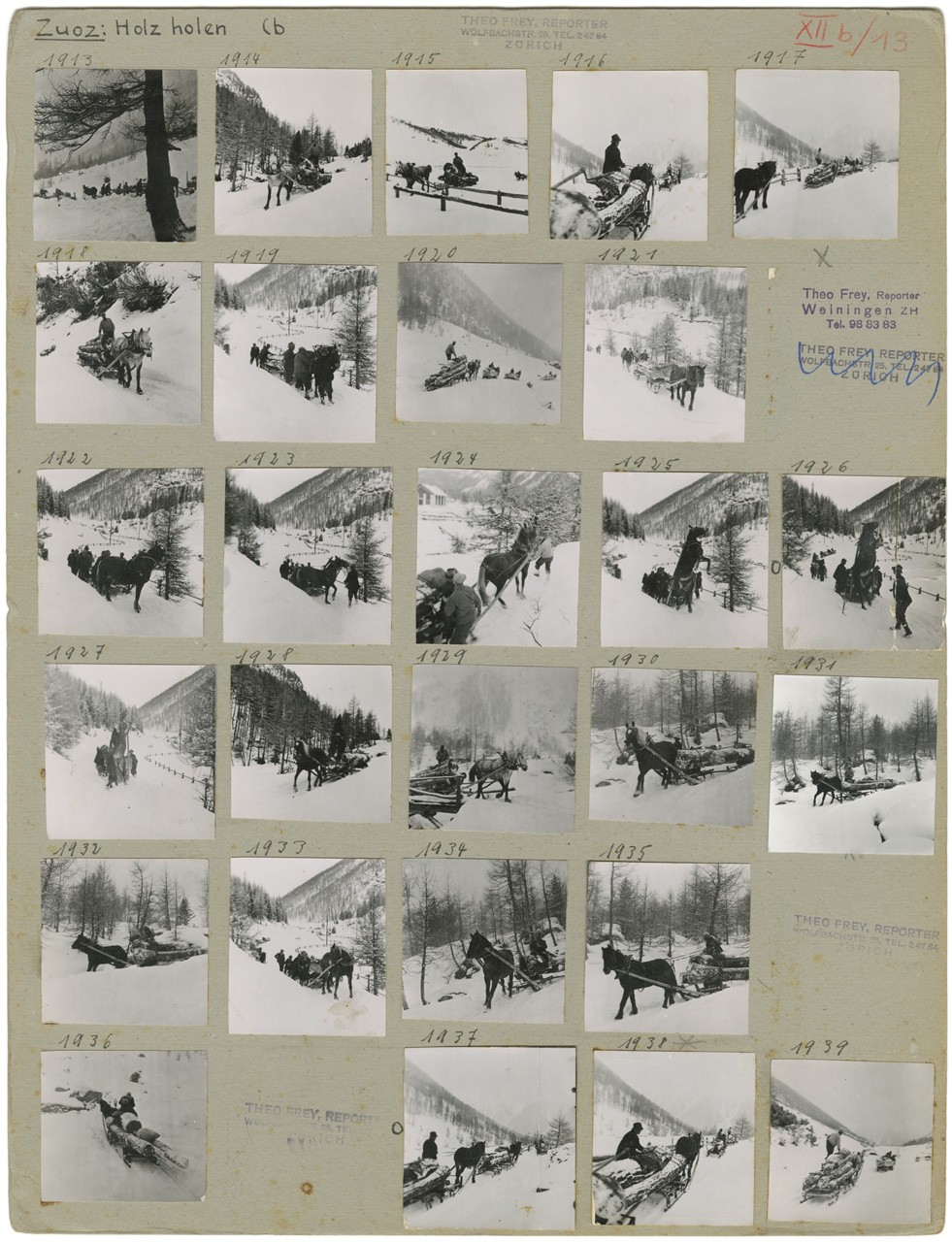

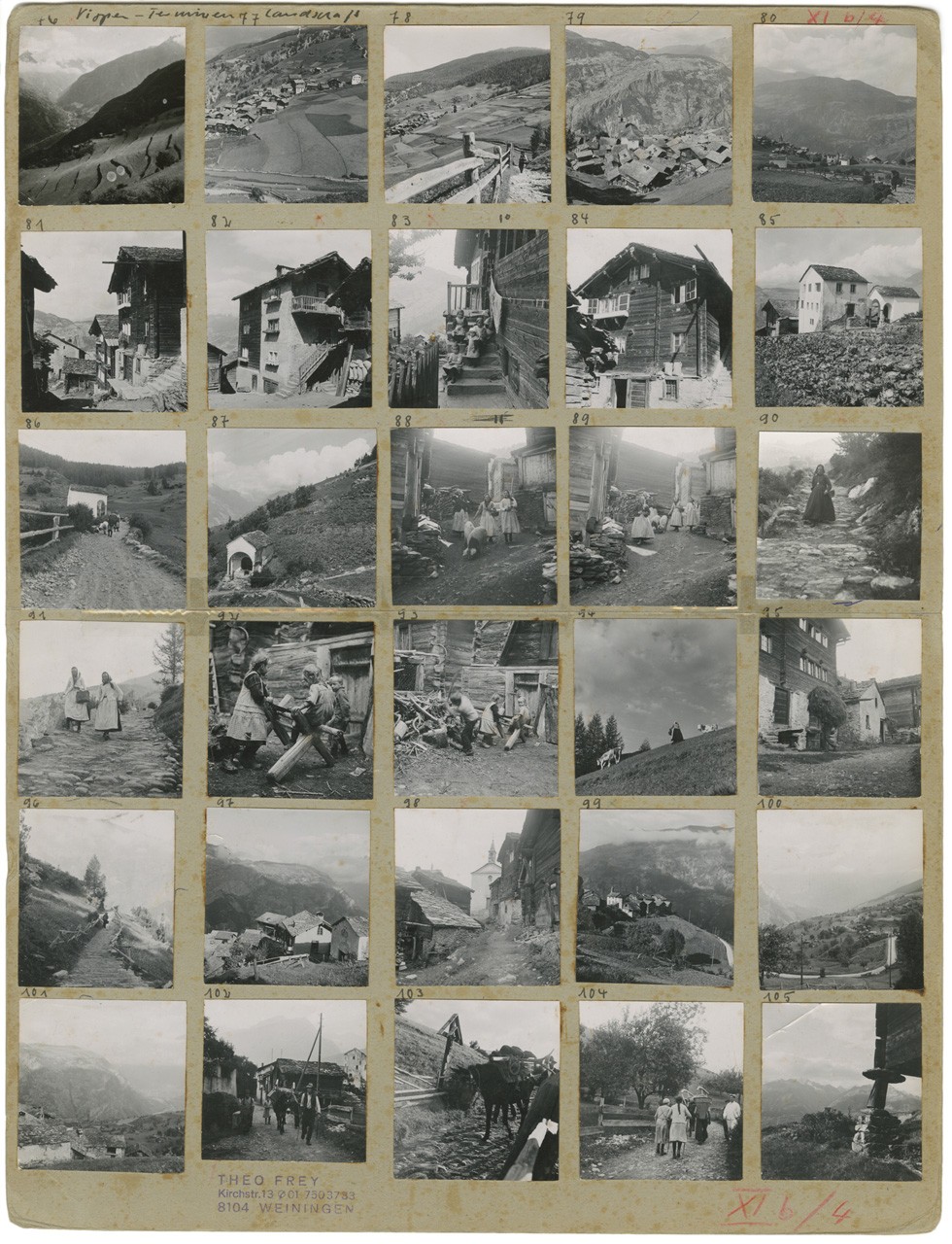

Theo Frey's photographic estate comprises about 100,000 negatives, 3,500 contact sheets, 21 scrapbooks, and thousands of prints. In 1989, the Swiss Confederation acquired Frey's archive, and in 2006 it was given as a permanent loan to Fotostiftung Schweiz, where it has since been maintained.

Theo Frey's photographic estate comprises about 100,000 negatives, 3,500 contact sheets, 21 scrapbooks, and thousands of prints. In 1989, the Swiss Confederation acquired Frey's archive, and in 2006 it was given as a permanent loan to Fotostiftung Schweiz, where it has since been maintained.

Seeing Frey's contact sheets juxtaposed with your photographs has such an impact on how I view yours. Is this something that you planned to do from the beginning? Does the sequence at all mirror your discovery of connections between your images and his?

I imagined weaving his contact sheets with my work early on but decisively didn't spend much time in the archive to familiarize myself with his images much before photographing myself. Instead, after shooting, I spent a few weeks selecting one contact sheet from each village to represent it, twelve in total. The contact sheets were compelling to me because Frey rejected the notion of being an artist, and yet these objects were so artful and emotive. Then, of course, they're also imbued with the patina of time. Within the contact sheets, there may be thematic or visual connections that can be found in my photographs as well. The sequence is mostly chronological, following my route around the country, with a few exceptions. When we exhibited the work at Fotostiftung Schweiz, the contact sheets were hung like anchors on the wall with my images moving fluidly around them, up and down the wall. We showed some of the archive folders in a vitrine, which felt like a physical manifestation of that “weight” you referred to. The book, published by Edition Patrick Frey last year, features them like periodic pauses. In the exhibition opening at Robert Morat Galerie, we've decided to show a more restrained selection of images and give the twelve contact sheets their own wall.

What were some of the most difficult things for you about this project? Are there things you will avoid doing the next time around or things that you learned that you plan to incorporate into your next project?

The sublime nature of Switzerland is an important aspect of the landscape and present in my work, however, in a way, this was one of the most difficult things to confront as a photographer. Everything is so beautiful and clean, and so there are a lot of images that need to be made in order to move past the postcard scenes. I think that's true of many projects, and I certainly learned this making work in the South. The most compelling images aren't usually the things you see when you first arrive in a place, it takes a little time to look beyond those subjects.

I imagine that as director of Light Work you must witness such a variety of approaches to the process. Does watching so many different people create influence how you work?

I'm grateful for many aspects of my role at Light Work, but one of them is certainly the breadth of work that I'm able to see on a daily basis because of it. It's difficult to say exactly how the artists that Light Work supports influence me, but I'm absolutely inspired by everyone that we work with and often influenced and motivated by them as creative human beings.

What are you working on now, what's next!?

I've been working on a long-term project in Syracuse for the past few years, which I've just published some early images from as part of LOST II, a box set of books by twenty photographers, each looking at a different city. That book can be ordered on its own from the publisher, Kris Graves Projects.

Additionally, I've recently started looking back at some photographs I made in Italy while I was a visiting artist at the American Academy in Rome in 2015. I'm shaping them into a book as well. I'm excited about this work, because it's a bit of a departure for me—the photographs are also connected to place, however much more personal and conceptual in nature. I hope to share more on that this Fall.