Known for his documentary approach to subjects that range from sublime to ironic, the California-based artist John Divola has mined the territory between photography and conceptual art for more than 40 years. Two of his best-known and iconic series from the 1990s will be on view at Yancey Richardson this June. In Isolated Houses Divola uses the vernacular architecture of the California desert to explore existential themes of isolation and desire. Dogs Chasing My Car in the Desert reveals the age-old chase between man and beast with a wry and philosophical edge.

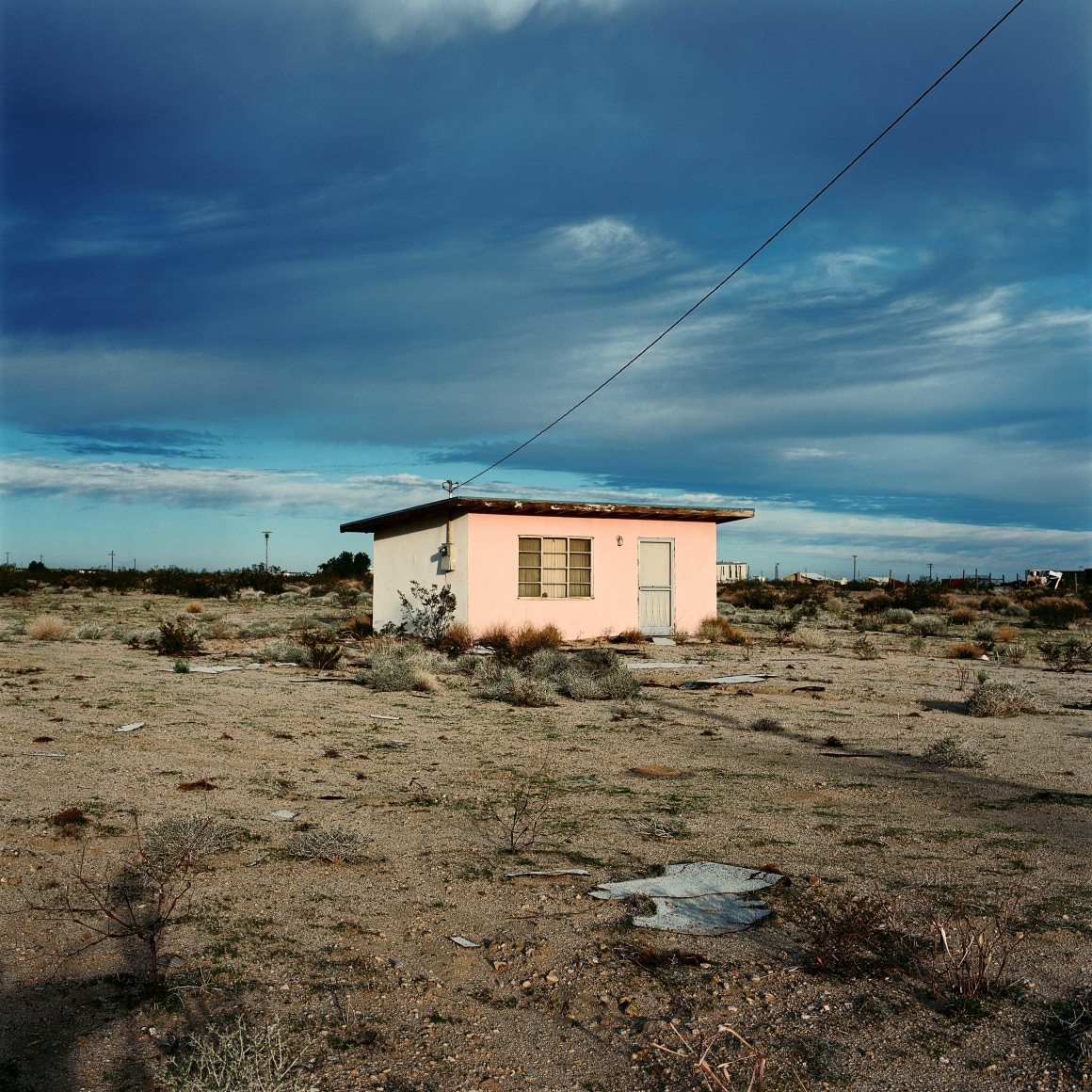

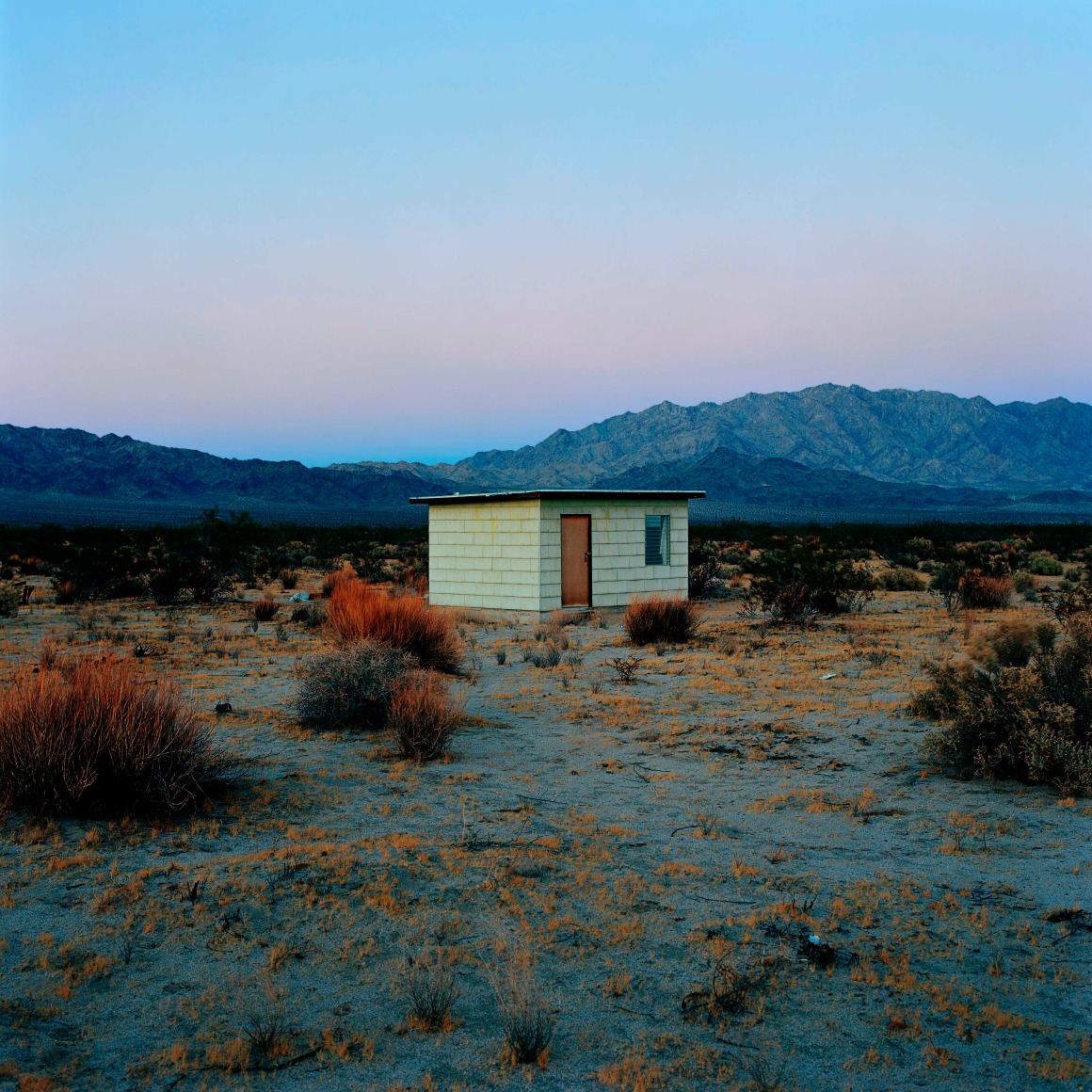

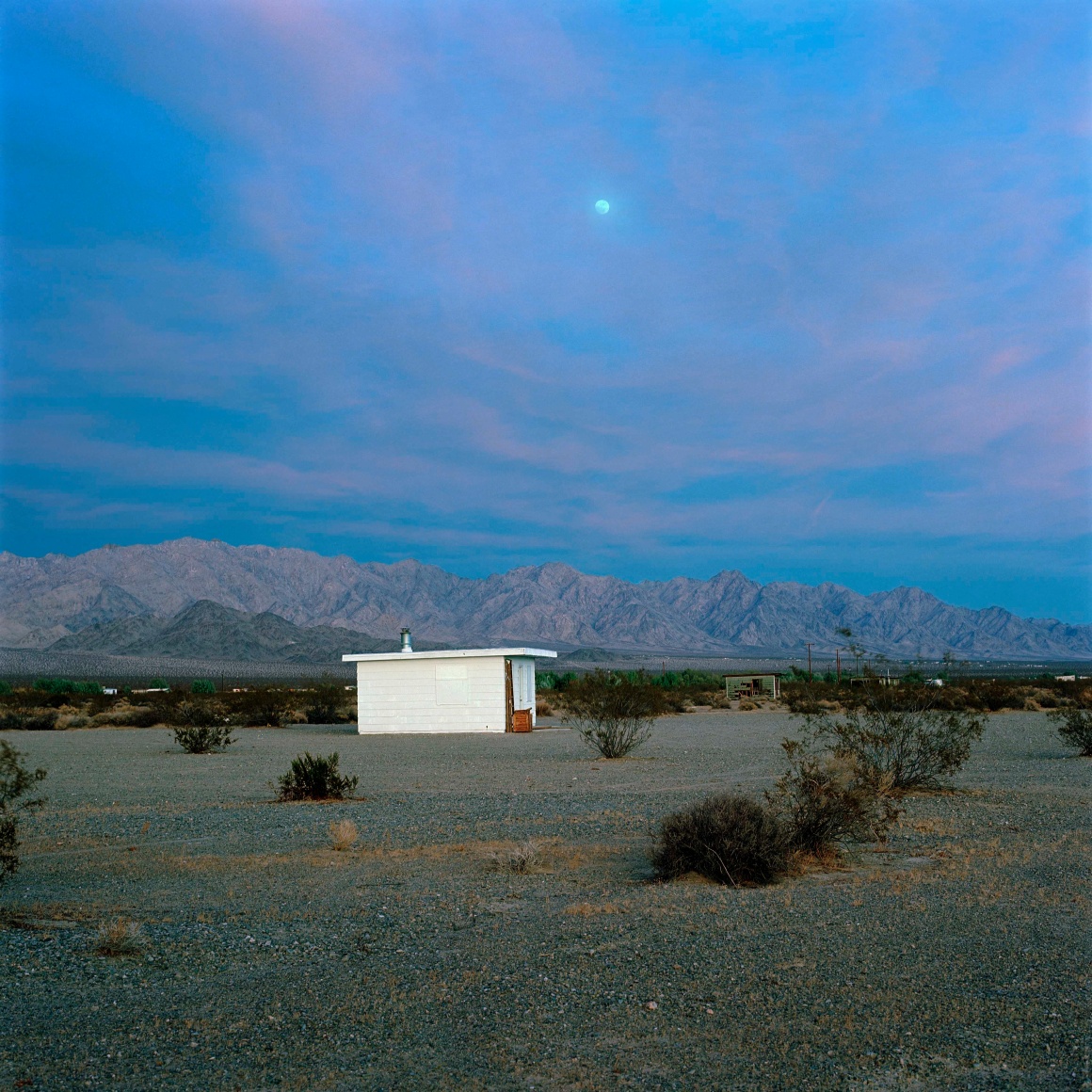

Photographed between 1995 and 1998, the images in Isolated Houses were all made in the high desert of Southern California, including the east end of the Morongo Valley Basin, Wonder Valley, and surrounding the town of 29 Palms. The small, simple box-like structures sitting alone on the vast desert plain are framed in square compositions, echoing the geometry of the flat landscape. They encapsulate the artist’s career-long interest in the tension between specificity and abstraction in photography. Illuminated by the extraordinary western light, the structures wear their neglect with a dignity that elevates their humble existence. The artist notes, “The desert is not empty. However, it is vacant enough to bestow a certain weight to whatever is present. Add this to a heightened awareness of your own presence and the desert can take on an existential quality.”

While traversing the desert region working on Isolated Houses, Divola frequently came across dogs who would chase his car. In 1996, he started to capture portraits of the dogs while in motion with a motorized 35 mm camera and high-speed film, evoking the spirit of Eadweard Muybridge’s exploration of stop motion photography. The work resulted in the now classic series Dogs Chasing My Car in the Desert, a collection of grainy, black-and-white images that look at the herding relationship between man and animal with a slightly comic approach.

"With one hand on the steering wheel, I would hold the camera out the window and expose anywhere from a few frames to a complete roll of film," Divola explained. "Contemplating a dog chasing a car invites any number of metaphors and juxtapositions: culture and nature, the domestic and the wild, love and hate, joy and fear, the heroic and the idiotic. Here we have two vectors and velocities, that of a dog and that of a car and, seeing that a camera will never capture reality and that a dog will never catch a car, evidence of devotion to a hopeless enterprise."