In his debut solo exhibition in LA, Carlos Jaramillo explores the athletic and cultural event "El Clásico De Las Américas," California's largest charreada, a multi-faceted rodeo event descended from Mexico following Spanish colonization, Jaramillo captures the event in all its energy, beauty and resiliency.

GGLA serves as an extension of the charreada, dirt floors and hay bales lending a texture and smell reminiscent of the events, with the artist frame and other installation elements only heightening this experience. Through Tierra Del Sol: LA Jaramillo uses charrería as a means of unpacking the ways in which culture is preserved and passed down, assailed and protected and lived in all of its complexities and contradictions. From the days in which large swaths of Mexican land were converted by Spanish colonists to cattle lands, hierarchies of power and subservience were created with indigenous and mestizo peoples being excluded from the role of the charro or cowboy. Thus when shortages of capable cowboys allowed these subjugated people to assume roles of power, namely riding horses and roping cattle, charrería was born as a means of showing off one's skills while performing a mastery of a role from which many people were previously excluded. As urbanization, migration and assimilation have largely done away with the hacienda system, the discipline has taken on new meaning as a means of embodied cultural preservation, the various events and pageantry connecting to traditions and a way of life predating their participants by hundreds of years.

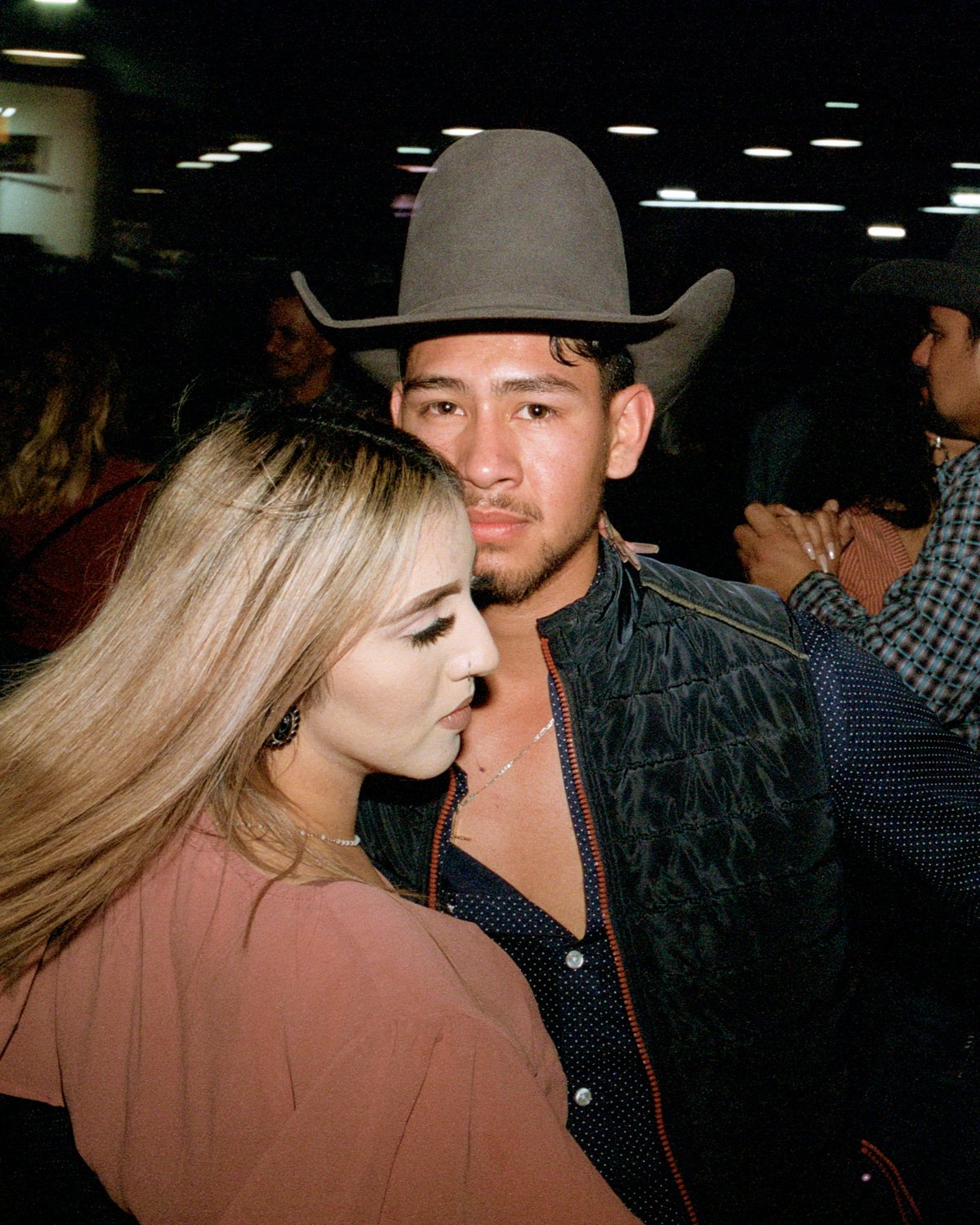

Born in the small border town of McAllen, Texas, it was in his adoptive hometown of Los Angeles that Jaramillo felt a proliferation of Mexican people, tradition and culture reminiscent of where he grew up. Upon the first few months of living in LA, Jaramillo found himself at the Pico Rivera Sports Arena, an arena specifically built for these events in the late 70s. As a first generation American of Mexican and Colombian descent, Jaramillo took particular interest in the young people at the event, setting up a portrait studio where he could document these earnest participants. In an age in which so many groups of people are forced to negotiate their hybrid identities. There lies a deep beauty and resonance in seeing these young people maintaining old Mexican traditions, while growing up in such a diverse metropolis as Los Angeles and in a country that is often resistant to those who deeply embrace their own identities.

Exploring everything from the formal qualities of the artist frame to the installation of the gallery, Jaramillo uses varied means to reinforce the imagery and feel emanating from the artist’s photographs. From the first entry into the gallery the scene is set by the loose dirt set under foot, hay bales strewn throughout the space providing a clear connection to the events of the charreada. Hanging on a nearby wall is an energetic diptych of photographs, horse and rider blurred in animated suspense, with some frames wrapped in aluminum Modelo beer cans. In the back room of the gallery a near life size vinyl printed image wraps across the gallery’s wall depicting a group of young escaramuzas, an exclusively woman led discipline within charrería in which teams of women perform elaborate synchronized choreographies atop horseback while sitting side saddle, wearing vibrant dresses harkening back to Mexico’s War of Independence. In a shed connected to the gallery Jaramillo has projected a video featuring an older charro deftly performing a series of rope tricks. Tierra Del Sol as a series of photographs and as an installation pays homage to the beauty and strength of charrería, providing a glimpse that might feel familiar or entirely new.