The following is an essay by painter Pat Perry. For years we have celebrated his sketchbooks, murals, travels and paintings, often depictions of Midwest America and the culture of moving through large parts of the nation. Ahead of his new solo show, Sensemaking, at Hashimoto Contemporary from October 16—November 6, 2021, we publish this work from Pat.

Mideast and Midwest

The War in Afghanistan started on a Sunday in 2001. Over the years, I’ve felt envious as slightly older friends of mine have recalled being part of the anti-war movement since the beginning, and throughout the 2000s.

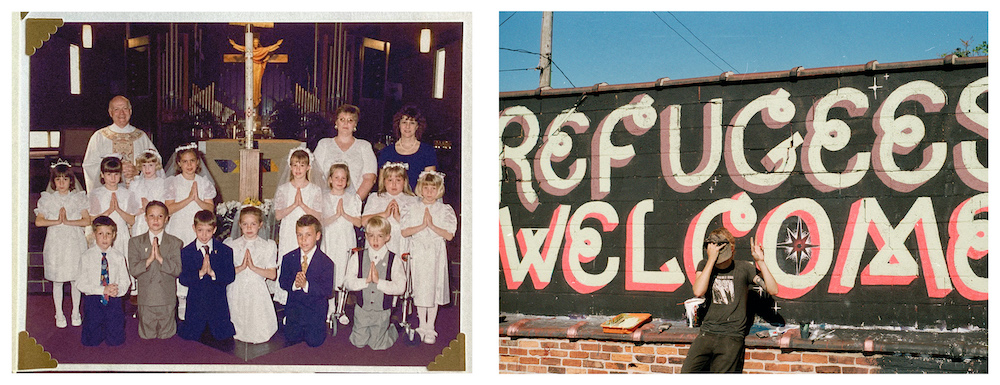

When the war started in October, I was still in elementary school. My Grandma bought me a “These Colors Don’t Run” shirt with an American flag and the twin towers on it. On the Sunday the war began, I was at Catholic Mass with my family at a church in West Michigan, surrounded by corn fields in all directions. The airport in Kabul where you’ve been seeing chaotic scenes on the news all week is the same airport where some of the first airstrikes were reported. That week, my Mom played us the Mr. Rogers episode on Conflict and War.

The two major wars in the Middle East continued throughout all of my remaining grade school and high school years. One afternoon after school in 2004, my best friend and I watched the Nick Berg decapitation video in his basement while his parents were at work. I threw up. I never told my Mom we watched it until earlier this week while talking to her on the phone. At Mass each week during Prayers of the Faithful, the names were read aloud of different sons and daughters from our parish fighting in Afghanistan or Iraq. My cousin enlisted in the Marines and still works on fighter jets at a base in Texas. Several enlisted members from our Parish in Alpine Township were killed in Iraq or Afghanistan.

By the time I graduated high school, I had replaced religion and Civics lessons with CrimeThInc books and an Adbusters subscription. I threw away one life guidebook, and tried to rewrite a new one from scratch, Guidebook Two. Plus zines and Youtube. Obama was President and routinely promised we would be leaving Afghanistan soon. The War in Afghanistan was often compared to Vietnam. I learned what the Mujahideen was. I read Howard Zinn. My new guidebook said US wars were only supported by monsters, and my upbringing sometimes embarrassed me.

Both guidebooks turned out to be astonishingly wrong in their own ways. They were astonishingly right in other ways. My chapter 1 guidebook came with a trust in leaders that would be laughed out of the room these days - equally loud, no matter where you live or which bubble you inhabit. There was surely some opposition to both wars, but my small community seemed to overwhelmingly support them both, especially in the early years. Hindsight has left us nearly doubtless that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were huge mistakes. Those huge mistakes were full of thousands of heartbreaking small mistakes. The brunt of those mistakes were bore by everyday American families. They were bore even more so by everyday families in Afghanistan and Iraq.

You may feel there are tons of mistaken views running rampant in small-town America, especially in the flyover states. I don’t disagree. I also know I’m lucky for the family I have, and to have been raised where I was. I stayed in Michigan and live in Detroit. My parents and immediate family now live in Tennessee. To this day, I’m not sure I’ve seen quite the same quality of mutual aid as what the moms and grandmas provided at Catholic church.

Guidebook Two was wrong too. Throughout my twenties, I claimed to be in solidarity with blue-collar workers at activist camps and meetups all over the country. Those blue collar workers turned out to be a lot of the same “uninformed suburbanites” I used to simultaneously deride. Turns out, they’re not all monsters. Educated culture workers, urbanites and activists make up what’s been dubbed, the creative class. Their moral-superiority and self-assuredness is something I’ve complained about often. To cast endless judgement on the judgemental though, can turn into its own unconscious trap: another lockstep of endless volleys on the tennis court of the culture wars. That same batch of performative subcultural elites, are the same artists and activists who have introduced me to all sorts of new important ways of contextualizing the world. Turns out, they’re not all monsters either.

After Both Guidebooks

Thousands of lives were destroyed in events that affected me only peripherally, as they loomed in the background of my childhood and on into the rest of my life. Some years ago I made a painting about it. The same year I made the painting, I visited Iraq for the first time. The way Iraqis and Kurds talked about the Iraq War was humbling and different than what I thought they’d say. The couple times I flaunted my ideology to show I was one of the more enlightened Americans, it was met with quiet politeness, silence, and a subject change. A lot of the kids played Fortnite. One morning, an Iraqi Kurd told me about his family members that were killed in Halabja.

Some retired Iraqi military men showed us which hills had landmines left from the Iran-Iraq War. They took us to the mountains to shoot AK-47’s, sing songs, and go camping. Minus the language barrier and AK-47’s, the camping trip was a mirror image of camping trips I’d been on with my Dad and uncles in Northern Michigan growing up. After giving me a ride to the airport in his car, a 230-pound Peshmerga soldier teared up at the airport in Slemani when he told me the story of rescuing naked, starving women from a basement of an ISIS-held house. On my way home, a US Marine on my plane told me about how during the war, he’d been blown up twice by IED’s and survived.

These wars have been going on for most of my life. Like almost everyone my age, I had tasted weird flavors of sadness about them from different venues at different ages: from cable news in elementary school, or from a church lectern in middle school. From NPR in high school, or from Assyrian Immigrants in Detroit in my mid-20’s. From the Middle East in my late-20’s, and most recently, from an NYTimes iPhone app, watching videos of real human beings desperately clutch the outside of a giant metal airplane as it flew away up into the sky.

In some ways they’ve seemed to make less sense over time. Guidebook One, though slightly dogmatic and wrong, offered a clear understanding. Guidebook Two, though also slightly dogmatic and wrong, offered a different clear understanding. Chapter Three of my life hasn’t come with a comforting guidebook like Chapter One (religious/conservative-farms-and-suburbs) and Chapter

Two (Noam-Chomsky-wikipedia-anarchyland) did. I miss the sound of a hundred kids and old people and parents singing together with organ music. I miss howling in the forest with a hundred wide-eyed direct-actors, preparing to blockade a frack-waste facility. Though I know nostalgia is dangerous, it doesn’t stop my missing a feeling of narrative-clarity when huge events in the world happen. An appetite for clarity is natural, but a weak stomach for unanswerableness is what kills curiosity.

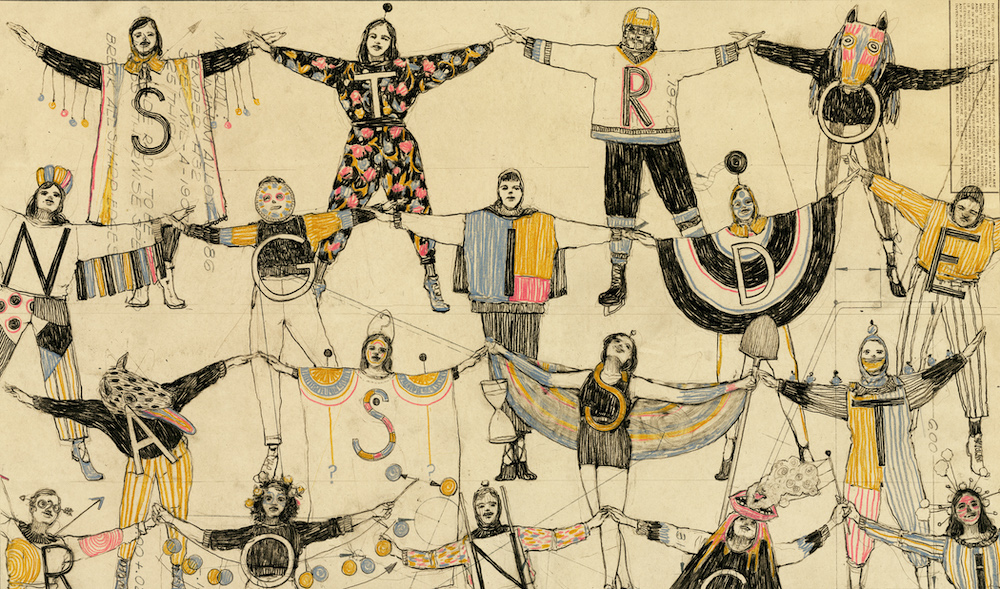

It’s natural to want to understand events in the world and to respond to them. It’s also natural to want to be a part of the action. For better or worse, those impulses have guided most of my adult life. I also think it’s natural to feel called to stand up for what you think is right; It turns out, that’s what almost everyone is doing in their own way. Everyone feels like an underdog. Almost every corner of the culture, especially social media, rewards us for being bold, unwavering, and self-assured. I glare at a “Use Your Voice” Shepard Fairey Billboard that implores me to speak up every time I drive East on i94 through Detroit. We are relentlessly trained to see ourselves as the main character of a story in which we are part of an exclusive tribe. Our tribe of underdogs are the heroes who are courageously fighting a formidable enemy, against all odds. Whether you’re a climate activist, or a member of ISIS, or a QAnon shaman, or a train-riding anarchist, the story is the same.

Chapter Three of my life so far has had something to do with recognizing that truly lessening suffering maybe has less to do with understanding the world, or playing an oversized role in it. It may not be about constantly “using my voice”. I’ve had to incessantly remind myself that the movie isn’t about me. I won’t even be there to see how it ends. Honestly, it’d be lucky to even be cast as the liquor-store clerk that gets a one-line cameo somewhere along the way - most of us are extras.

The best artists have always tried to show us that we ought not feel the need to be cast in grandiose roles in order for our personal stories to be captivating. Fred Rogers seemed to understand that truth perhaps better than anyone. If there was a third Guidebook, it would probably say something about how one seductive story of greatness can greatly endanger a thousand stories of goodness.

Chapter three of my life has ushered in the difficult task of making peace with this fact : as individual sensemakers, we are flawed reasoning machines. I’ll never feel that I understand the geopolitical ins-and-outs of the Middle East wars in a satisfying enough way that their horrors are somehow put to rest. As Kant said, “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.” Though as noble and natural a task as any, sensemaking is an all too human act.

Reaching a level of expert knowledge on even one major world issue is rare for anyone, let alone the perplexing multitude of issues that dominate news feeds every single day. If you’re like me, you’ll count yourself lucky the day you can justly claim expert knowledge on even a single one of them. Epistemic humility is a fancy term for another idea Kant helped popularize that, at its core, means: be cautiously humble about what you think you know.

I used to fear that admitting a limit to our own sensemaking was to somehow resign to apathy. I’ve spent whole years of my life blanketing judgement in generalized ways over whole groups of people. Whether you’re dismissing Middle Americans writ large, dismissing all Afghans and immigrants, or dismissing the whole creative class, the error stems from the same human failure: being unable to stomach living with uncertainty. Admitting not-knowing, in the end, is actually a way of becoming more thoughtful. The digital age demands that we tolerate a spectacular amount of uncertainty, and that we consciously fight to stay curious. After all, artists are supposed to talk to everybody.

—Pat Perry, August 2021