François Ghebaly is proud to present The Is of It, New York-based artist Ludovic Nkoth’s newest exhibition at the downtown Los Angeles gallery. “It’s with such a profound happiness. Such a hallelujah. Hallelujah, I shout, hallelujah merging with the darkest human howl of the pain of separation but a shout of diabolic joy…,” or so declares Brazilian author Clarice Lispector in the breathless first lines of her 1973 mystical novel Água Viva. Later translated to “Stream of Life,” Água Viva records in rhapsodic, stream of consciousness monologue the meditations of a young painter on time, language, and the artist’s call to the living moment. “Everything has an instant in which it is. I want to grab hold of the is of the thing. These instants passing through the air I breathe: in fireworks they explode silently in space.”

For Cameroonian-born Ludovic Nkoth, whose painting practice has long held a mirrored glass to his own diasporic experience in the US, the words of Ukrainian emigré Lispector offer a kind of twofold insight: on the one hand, a clarion call to seize and reside in the waking present––the “is”; on the other, familiar ruminations on the transitory and the impermanent. In his newest exhibition, The Is of It, Nkoth reflects on concepts of “home,” as a physical place and as a fleeting, ever-evolving idea, a moving image in the mind’s eye. Similarly evasive concepts––family, belonging, identity––have long been mainstays in the artist’s visual imaginary, where brightly hued, sensually impastoed figures regularly participate in the fictions and lived experiences that comprise his own identity synthesis. “Is home a place or a feeling?” asks Nkoth. “And how do we hold onto moments? A moment in its conception becomes always already in the past. How do we grasp, let alone memorialize moments?”

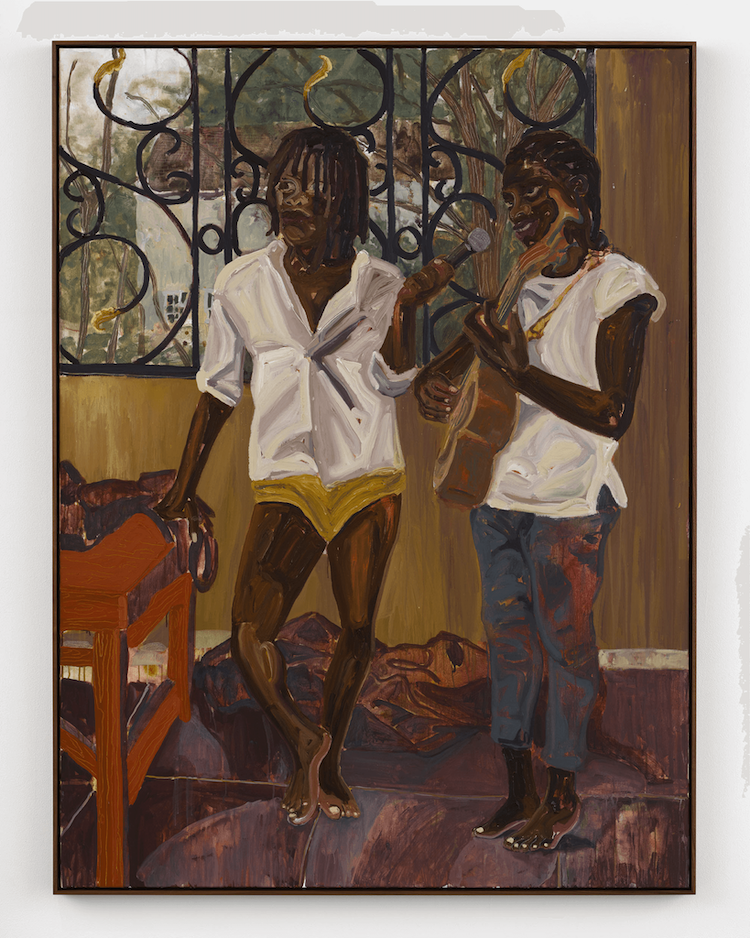

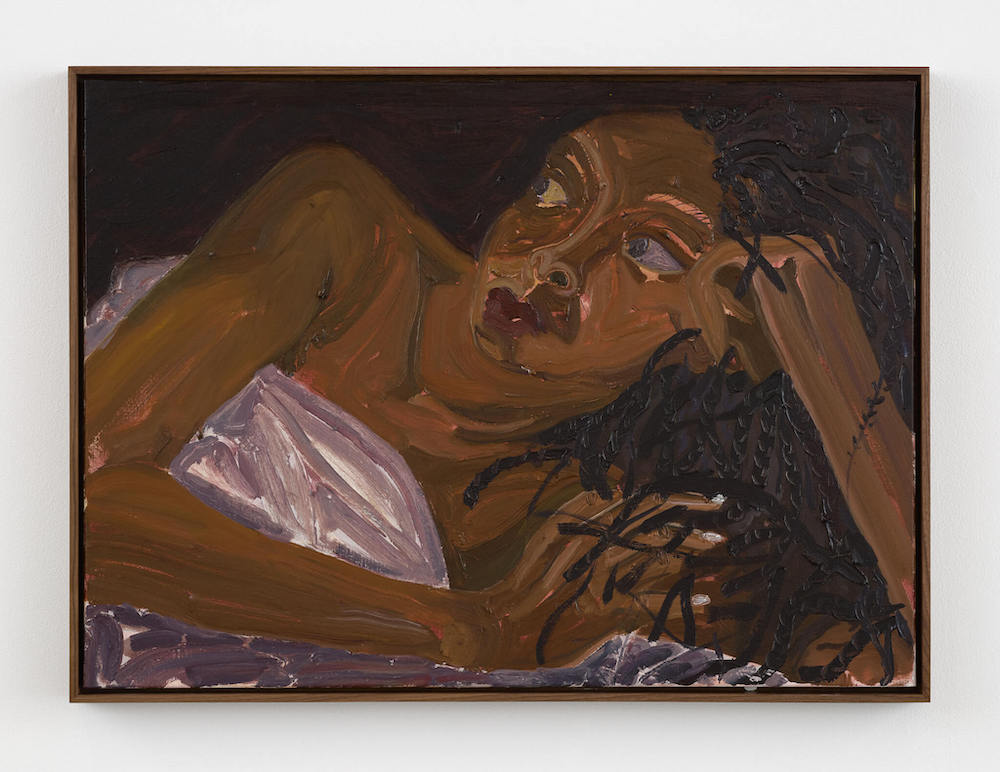

Between the twelve acrylic paintings and three watercolors that comprise The Is of It, nearly all were produced during a year-long residency at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Many reflect time Nkoth spent in the Montmartre’s Château Rouge neighborhood, home to multigenerational communities of West African expatriates, some with whom Nkoth broke bread and shared stories of leaving what once was home to build new identities and spaces. “Their sense of home is fluid, whether they choose so or not.” In works like High Notes (2023), Time is the duration of a thought (2023), and The shape of light (2023), Nkoth’s approach to capturing this fluidity, alongside Lispector’s eponymous “is,” is concretized in an almost in media res sensibility, where figures are captured in the midst of shifting moments and narratives. Two barefoot musicians linger in an interlude; a seated woman in a ruddy pink dress stares fixedly to her left; a young mother, infant in hand, grins towards someone just past the viewer. The sinuous linework of symbolists and expressionists like Edvard Munch becomes here an evident touchstone for Nkoth, loosely shaping the contours of figure and space while leaving glimpses of his vivid underpainting. “I think in the past I’ve made a few works that somewhat require the gaze of the viewer to be activated, or to interact with the space. But in these newer paintings, it’s almost as if the figures know that they are already taking up space in their own way. They’re able to simply exist within these windows that are canvases.”

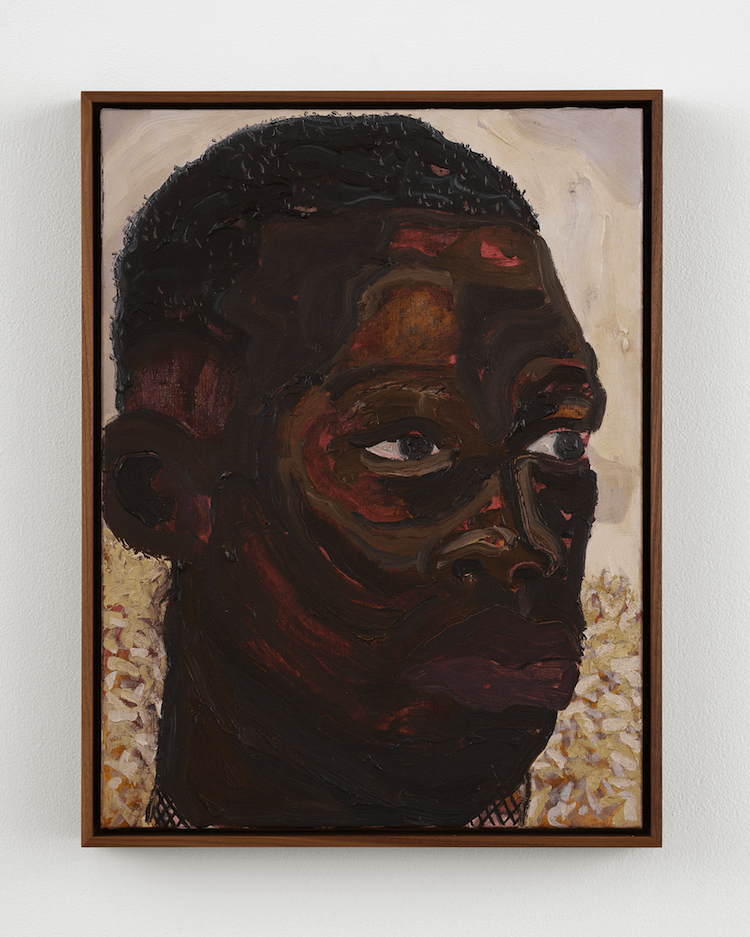

Prominent in the exhibition are Nkoth’s more classically styled portraits. The work How to surprise a mirror (2023) shows a young girl in an orange dress and white collar standing before a mirror; a jardiniere on a table and a small black cat frame her either side. At the center of the painting, the reflection of her right arm is doubled as though shifting in focus, demarcating her movement before the mirror in almost ghostly real time. Elsewhere, in works like Views from within (2023) and Soliloquy (2023), Nkoth expands the face and figure of his sitter to encompass nearly the entire canvas, at once conveying the fullness of depictions as personal and intimate as these, and at the same time holding to a tangible sense of reticence––perhaps a cue to the ineffability of life experience, personal histories kept close. “When we sit with paintings a little longer we’re able to look at them as mirrors, and use our own past experiences to reach toward a higher understanding of what’s in front of us.” For Nkoth, these higher understandings, the most profound essences of fiction and storytelling, are ready at hand in our lived realities.