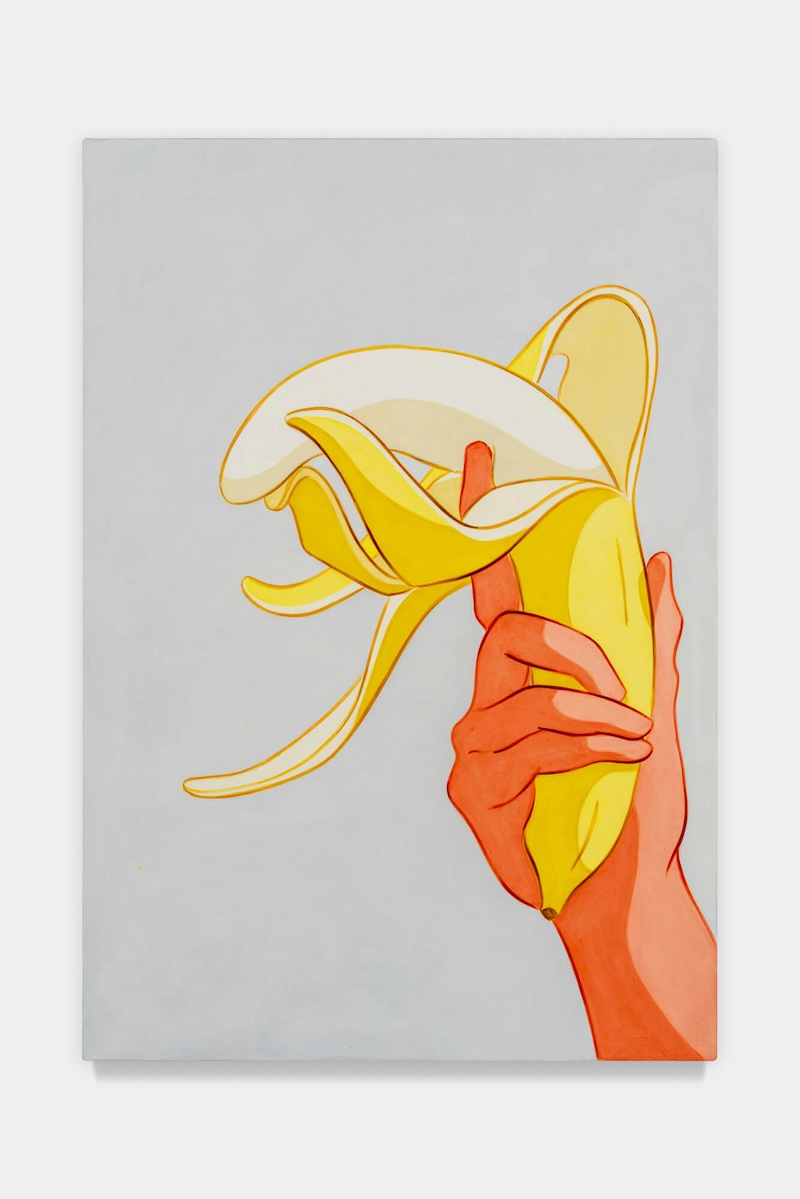

The thing I love about Ivy Haldeman is the way she let's you know the world isn't what it seems. You recognize everything but you are trying to figure out why something out of context feels really uncomfortably heavy. The empty bikinis: has something ominous happened to the person once wearing it? The close-up of what we can only assume are men in suits: are they making a deal for peace or agreeing to war? And in her new show at François Ghebaly, The Agreement, The Fool, and The Storm, they mention something that has stuck with me over the last few weeks: "Notions of ‘slippage’ are at the heart of Haldeman’s art and the exhibition is a study in the push-pull between image and power."

So the story is this: Bikini Atoll is a coral reef made up of a ring of islands that sits some 2600 miles southwest of Honolulu and 5000 miles from Los Angeles. In 1946, after decades of German and Japanese imperial control, the United States displaced the atoll’s Marshallese population and began to use the islands as a peacetime nuclear testing site. Over the next twelve years, the U.S. military deployed nearly two dozen hydrogen bombs on land, over the ocean, and in the coral reefs of Bikini.

To keep up with the Soviet nuclear program, the United States set off bigger and bigger explosions in the Pacific. Just as the testing was beginning, a Cold War-era race of reverse scale was launched 8000 miles away when French designer Louis Réard co-opted the atoll’s name to describe yet another mid-century provocation of superlative proportions, one that would come to define gendered aesthetics for decades to come: “the Bikini — smaller than the smallest swimsuit in the world.” In red, pink, and polkadot styles, Réard’s design is a central figure in Haldeman’s newest exhibition, The Agreement, The Fool, and The Storm.

So things are indeed, not what they seem in these paintings, and yet they have a heaviness in the most abstract of ways. A place of war also is directly connected to minimal bathing suit. A handshake in paradise also creates the potential of apocalypse. The sheer size of these works, almost mural size, overwhelm you with something rather beautiful and alluring; but underneath, every utopia has a direct line to dystopian results. —Evan Pricco