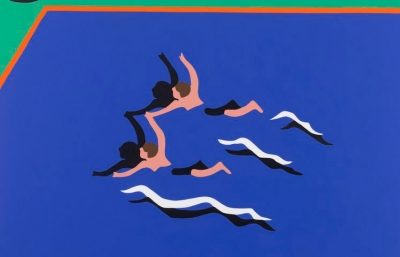

I often find myself thinking about a stranger for a bit longer than it’s comfortable to admit. Their perfume or cigar triggers a memory of somewhere I’ve traveled to long ago or have always wished to visit; the pattern of their blazer might remind me of a handbag passed from my grandmother to my aunt to myself. Like me, artist Angela Burson often lets her mind wander after encountering a peculiar stranger, taking her down imaginative paths steeped in memory and wonder. Her solo exhibition, Travelers, at Hashimoto Contemporary Los Angeles takes these moments as the points of departure for her newest body of work.

Before opening her solo exhibition, Burson and I (Katherine Hamilton) spoke about finding inspiration, developing her unique style, and how she imbues seemingly empty rooms with traces of full, beautiful lives.

Katherine Hamilton: You live in Savannah, Georgia, a city with unique vegetation and many different types of architecture. Though your paintings seem to take place in a “nowhere land” or somewhere liminal, do you see Savannah influencing your work? If so, what aspects?

Angela Burson: My work is not directly about Savannah, but of course my surroundings inform my work. Savannah is a historic city full of old buildings, old live oak trees, and historic cemeteries. It is hot and humid here, and ferns grow on the bricks, and Spanish moss hangs from the trees. I have always lived in old houses, and they have a certain presence. In my paintings, I often reference the windows, glass door knobs, arches, and other architectural details of my own home. The iron beds or cane tables in my works are examples of furniture I see in houses and antique stores here in Savannah.

I’m also really interested in your paintings’ flat, almost illustrative style. It reminds me of some of the work in the Magic Realism movement, where artists depicted fantasies or dream-like scenarios in “ordered” compositions. The symmetry and pastel palette also remind viewers they look at something constructed rather than real, much like a Wes Anderson film.

I do connect with the ordered, elegant world and symmetry of a Wes Andersen film. Visually, we are both very much about the fine details and complex palette. I also look at a lot of fashion photos from the past, especially ones that feature menswear. Like Wes, I’m concerned with depicting details that are real but not with showing reality. I like the freedom of nonreality. The blend of objects from different times seems very natural—my surroundings are composed of old and new things.

So, who are some artists you were looking at when you first started painting, and who are you looking at now?

When I first started painting, I would visit the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. I looked at an Ingres portrait, Max Beckman, DeChirico, Fairfield Porter, and Wayne Thiebaud, among many others. Portrait Miniatures were fascinating, along with folk art. I had a book on Albert Pinkham Ryder and Frida Kahlo. Lately, I have been looking at the work of Gertrude Abercrombie and other female Surrealists. I am inspired by Louise Bourgeois, Baltus, and Dominico Gnoli. I love so many artists that it’s tough to list just a few.

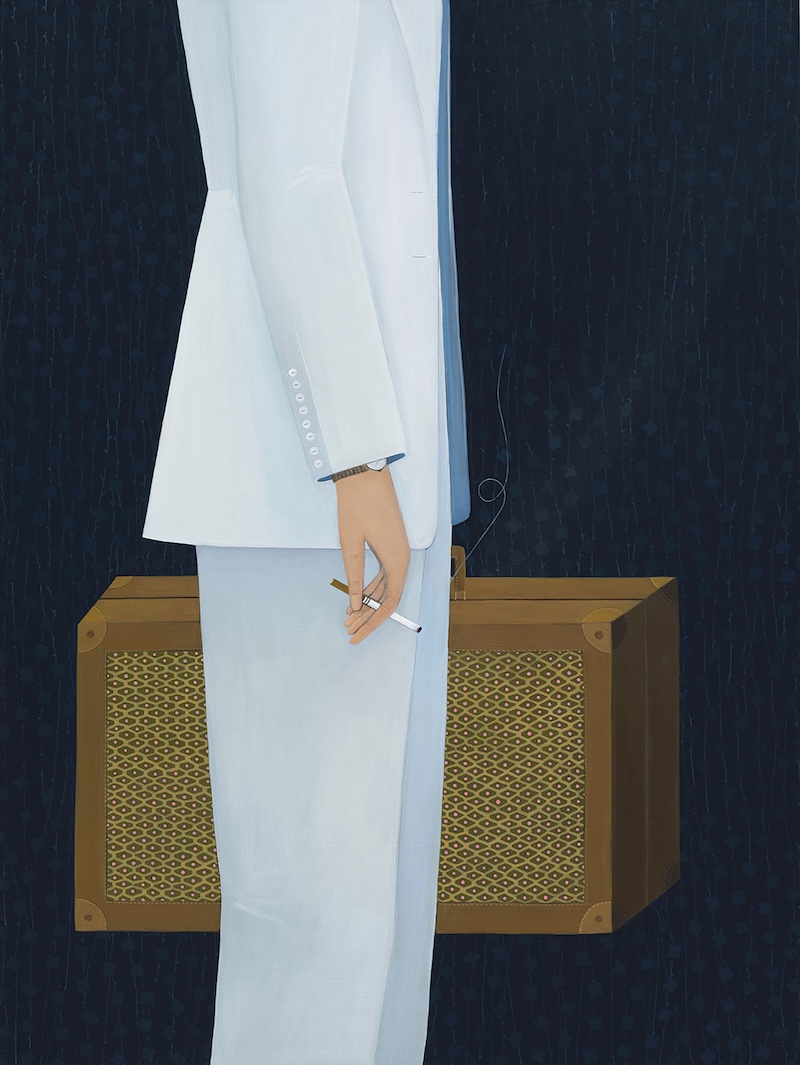

You’ve talked about how your painting practice focuses on “meaning-making in the relationships between objects,” as your work focuses on the formal qualities of objects and their arrangements or how possession might define an identity. What do you think our possessions reveal about us?

The objects and clothing in my paintings reflect us because we have selected them or chosen to save them. Whether it’s intentional or not, the choices of what we surround ourselves with always reflect something about ourselves.

I like to combine these objects in a way that suggests a narrative but is open enough for the viewer to complete this story. The figure’s identity in the painting is hinted at by the clues of the objects that build the narrative.

Would you consider yourself a collector of objects?

I keep objects from my family’s past that are meaningful to me, small things I’ve saved. I have a lot of plants, photographs, and other personal artifacts I have gathered that I draw on for my artwork. For example, I saved a little landscape folk art painting on a slice of a tree. The date is 1937, from my grandparents’ honeymoon at the Lake of the Ozarks. However, I’m not the type of person who goes out searching for a particular item to collect.

Thinking about your work and how objects can order the world reminds me of Jane Bennet’s 2008 book Vibrant Matter, which focuses on how non-human entities have shaped history. Bennet makes the argument that things have their own type of influential power. Do you believe the objects in your works shape the paintings’ narrative?

Yes, definitely. For example, the painting Spats depicts a garment worn over a shoe and ankle to protect the foot and ankle from rain and mud. Then, it became a fashion item during the turn of the century into the 1920s. This garment evokes a very specific time, a fashion from the past that I have noticed again—Michael Jackson wore them in his Smooth Criminal costume, or you might see them when watching Peaky Blinders.

The object creates a little story or fiction. Sometimes, something like that, spats, will jump out at me and spark a work of art. It could be an object, a vision of a figure, a room, or a piece of furniture to build a painting around. When that happens, I don’t question it. I write it down or save the idea and make a painting. I don’t seek out things to collect, but I do keep a collection of ideas.

Part of what it seems you’re interested in is how an object’s appearance (its pattern, its shape, how it looks near other things) creates our perception of the world, including how we create narratives about a person from a moment’s glance. The anachronisms in your works also build this world, bringing together objects and styles that did not exist together but can exist to us now as they were accumulated over time. When did anachronisms become interesting to you?

The clearest beginning in my interest in objects and anachronistic time in my artwork was during college. I moved into the top-floor apartment of a dilapidated antebellum house on Jones Street in Savannah. It had large windows, high ceilings with beautiful fireplaces, heart pine floors, and a wrap-around porch held up with a 2 x 4, along with a massive hole in the ceiling. It was a perfect mix of elegance and decay. The only thing in the apartment was an antique dresser with a mirror. It felt haunted and made me think, “who lived here and put their clothes in the dresser before me?” I don’t have an answer, but I still wonder what it would feel like to live in a different time and then be gone. You’ve left all these things behind, and other people may or may not have any interest or care about what has been important to you. Is there meaning in objects? Why is one spoon that went down on the Titanic in a museum and another spoon discarded? An object attaches itself to memory, or a memory attaches itself to an object, and it has a shifting history. Sometimes, its history is lost. If you have something old on your modern coffee table, it creates an anachronistic moment. This might be what I noticed and painted.

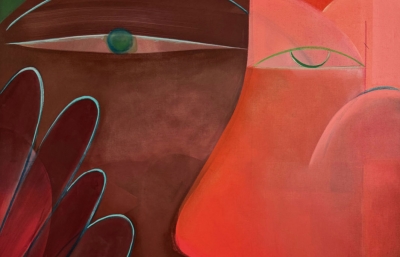

I also want to address your attention to patterns—it seems the world your figures live in is made of patterns, foregrounded on the clothes your figures wear or the objects they carry and subtly added to the backgrounds of most scenes. Do you depict these patterns from life? From imagination?

I use a template to draw the wallpaper pattern in pencil, and then I carefully paint the pattern. I do this for repetitive patterns like the hound’s tooth. I use these subtle background patterns to create texture and interest on the surface. The patterns on the dresses are more unrestrained, and I make those up. Sometimes, the background patterns connect the paintings to one another. They share a background to indicate they are taking place in the same room or space. In the paintings that don’t connect, the pattern creates a place for objects to inhabit, like in Spats.

I don’t usually paint patterns from life, but there are some exceptions. The dark blue floral pattern is based on a pattern I saw years ago. I like to use it when my figures don’t need to inhabit a specific space. I like classic, simple, repetitive patterns that are subtle and won’t overpower the paintings, like polka dots or pinstripes. I want it to draw the viewer in and activate the surface. It’s not perfect, and you can see my pencil line or places where I have had to improvise, but I like that.

Within the theme of patterns, you’ve also mentioned that the double is a repeating theme in your work: twins, mirror images, and symmetrical compositions. To me, the double produces an eeriness in the artworks—they have an uncanny likeness to our world but are not identical. Using a double also prods viewers to notice themselves looking, so we feel aware of ourselves looking at your work. Why is the double interesting to you?

There is always another side: a reality and an imaginary, life and death, an alternate universe. In the large diptych The Mirror, I tried to mirror the two figures, but I’m confident they are different. These subtle differences make me wonder: when you look in a mirror, is that reflection accurate?

The theme of twins has similarities to the mirror or reflection. It’s a double of something, but it also connects to having a close relationship with my sister. We are not twins but are close in age and always posed together in family photographs wearing dresses that remind me of the twins in The Shining or the Diane Arbus photograph Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey, 1967. We were always together, witnessing the same places and events. We share an understanding of certain people and periods but very different memories.

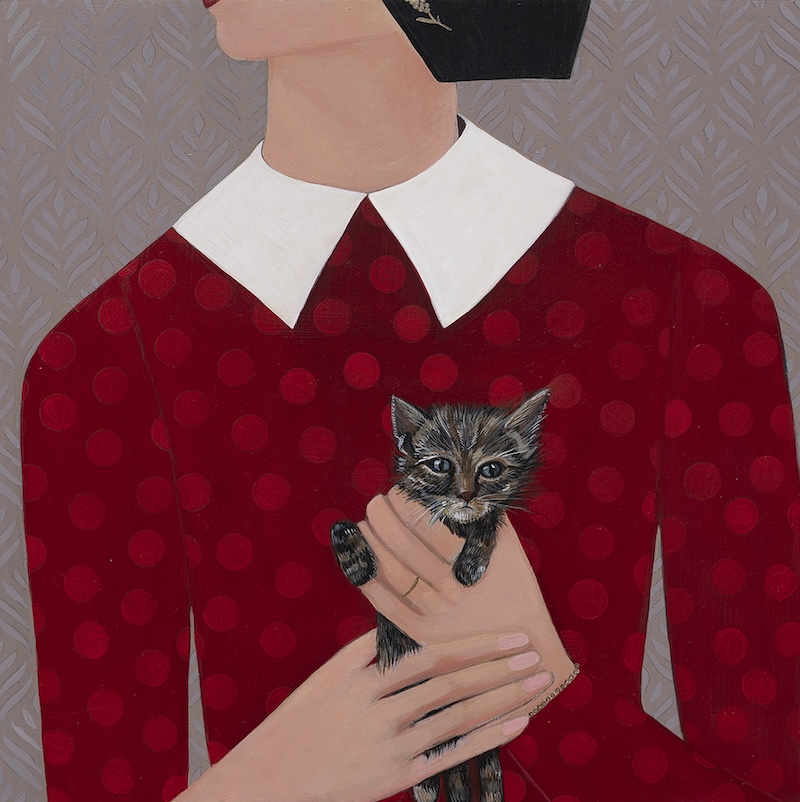

Though this isn’t the focus of this exhibition, it does seem that animals (owls, cats, dogs, horses) feature often in your work. Monarch, for example, features a delicate monarch butterfly on the figure’s hand and a sweet, languid cat in her arm. For you, are these the “signs of life” that you present in interior scenes? Or do they function on a more symbolic level?

Both. They’re signs of life and symbols. It adds to layers of meaning. There is a bush right outside my studio window that butterflies love to visit! I added the butterfly on a whim to the figure’s hand. It was an interesting multitasking moment for the figure holding the sleeping cat and this butterfly. Butterflies symbolize transformation or souls, but they also migrate long distances. It brings up ideas of travel and migration, a theme throughout the show.

What has been the most fun animal to render?

I have two cats and a dog. My daughter has a cat. All of them are in these paintings. They hang around watching us and looking out the windows. My favorite animal to paint is my tortoiseshell cat Wednesday. She is always present and watchful, following my every move, staring intensely at me like she is taking notes. I add the animals as witnesses to whatever has happened in the painting, the action that is not depicted in the scene but hinted at. For example, the dog witnessed the beer-drinking and pill-taking in the 1971 Living Room.

Since many of the figures are cropped, and there are no faces, the animals give a presence of life and symbolism that pulls in the larger world.

I love your interior scenes like 1971 Living Room. They offer provoking depictions of objects we don’t always see in paintings: I’m thinking of the Pabst Blue Ribbons cans or pill bottles on the coffee table. Over the years, which depictions of these small objects have brought you the most joy?

I absolutely love painting the beer cans and the pill bottles. My favorite part of the interiors is after I’ve labored over the painting’s composition, the positioning of the larger elements, the patterns and the colors. Then, it’s time to add the debris of a day. To me, that is what gives the painting life.

Angela Burson’s solo exhibition Travelers is on view through January 6th at Hashimoto Contemporary in Los Angeles. Note that the gallery is closed between December 24 - January 1. Installation and opening night photography by Megan Cerminaro.