Carl Kostyál is delighted to present a solo exhibition of new paintings by Scout Zabinski, her first with the gallery. As quoted from Martin Heidegger, The Origin of the Work of Art, 1935-37, “The artist is the origin of the work. The work is the origin of the artist. Neither is, without the other."

“There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art: That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself, therefore we habitually analyse its ingredients and define its limits. But painting IS impure. It is the adjustment of ‘impurities’ which forces its continuity. We are image makers, and image ridden.” Philip Guston.

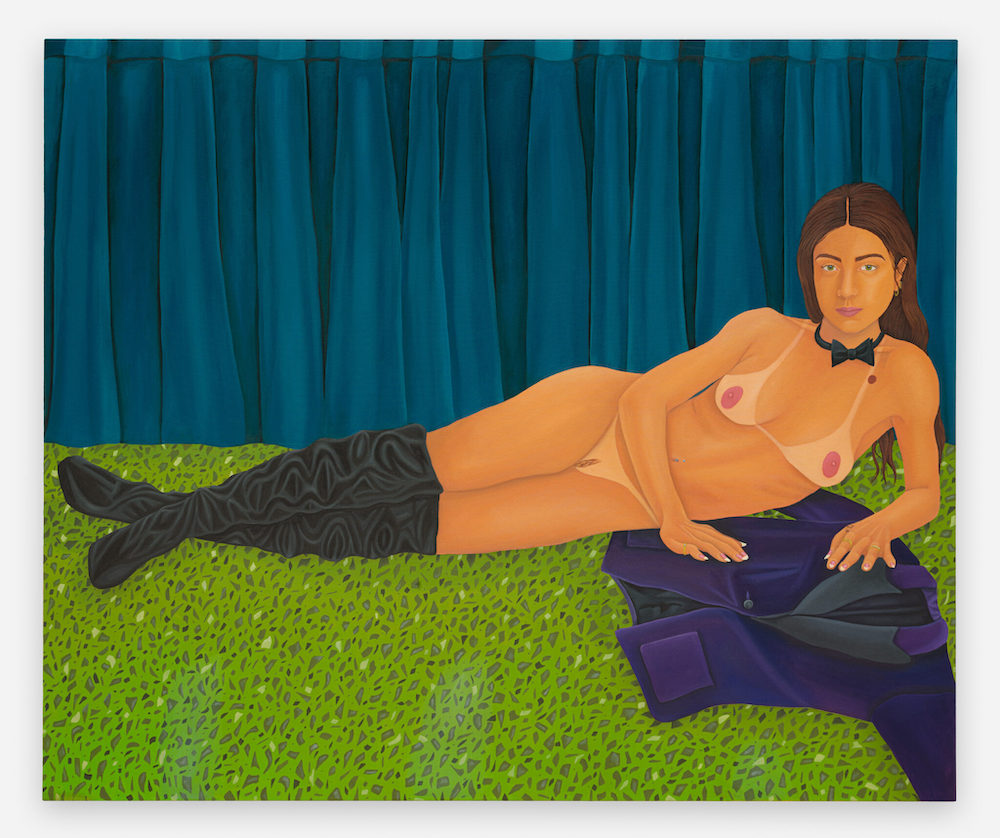

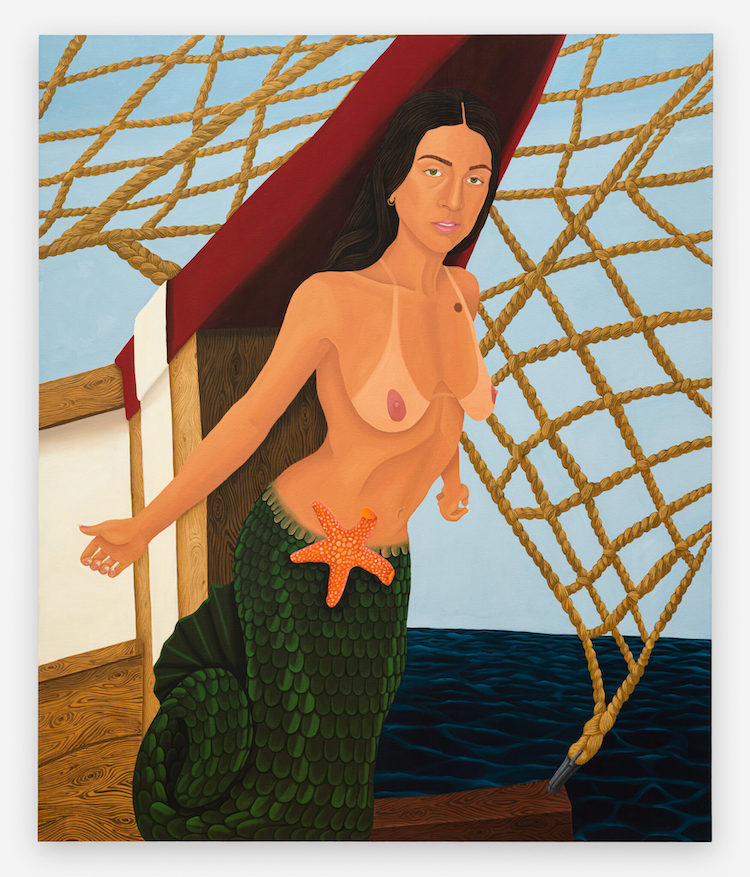

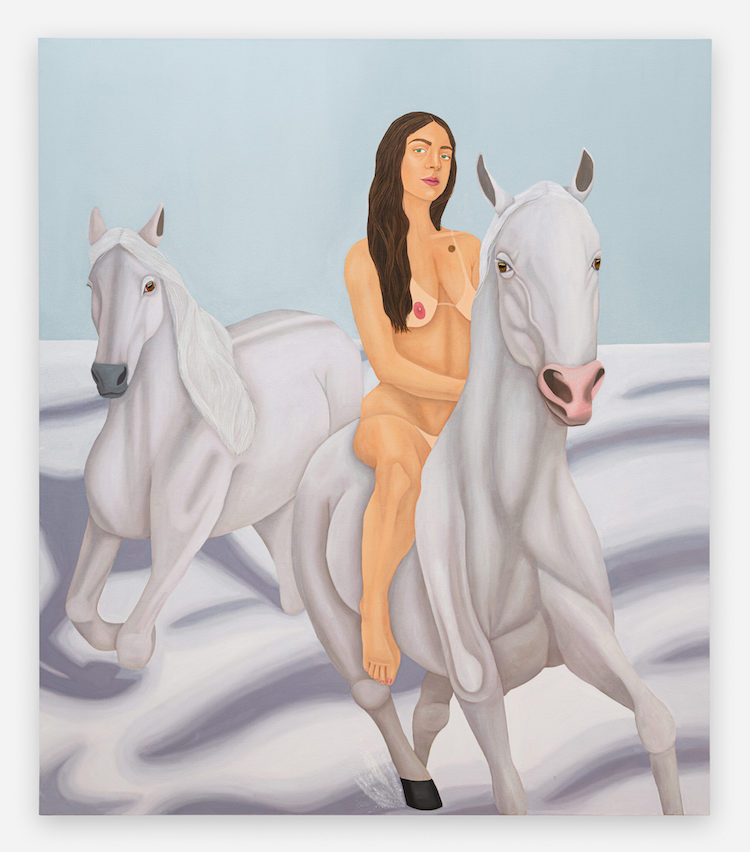

Scout Zabinski is a young American painter who uses her own, stylised nude image as the recurring central motif in her practice. Baring herself for her audience, painting is for her meditative, creative catharsis. She has described it thus: “My work is about trauma and recovery, self-reflection, self-image, addiction, abuse, eating disorders and the chaos of the mind in general. I paint what I know…Using my own image allows me to be completely free.”

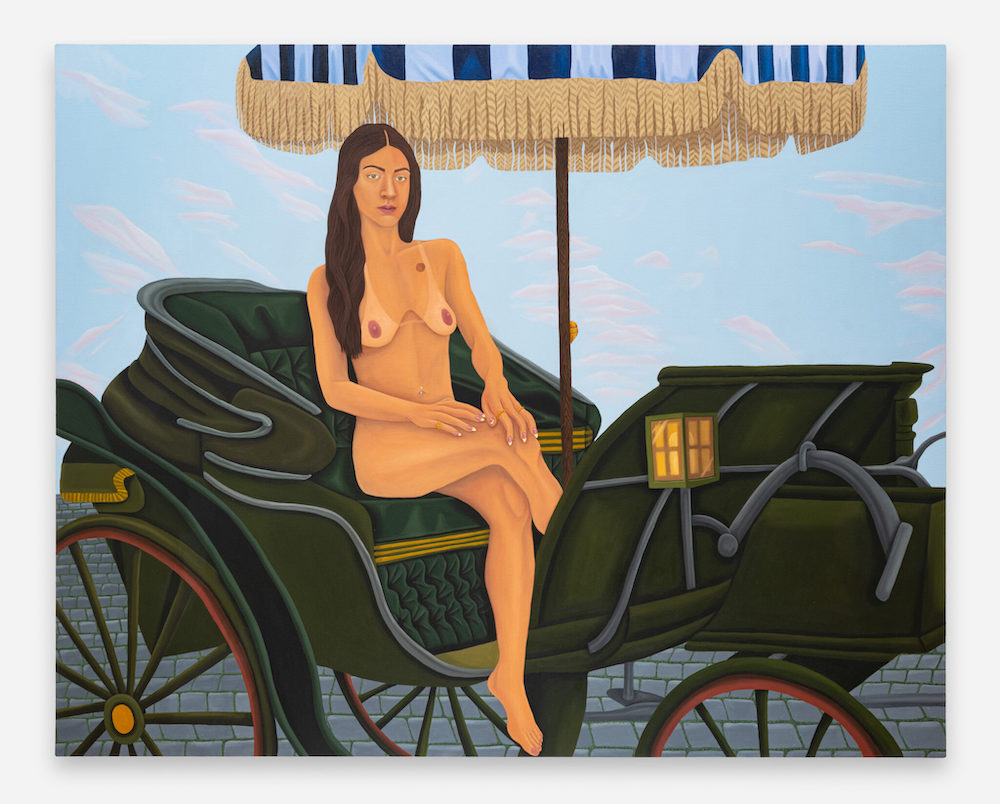

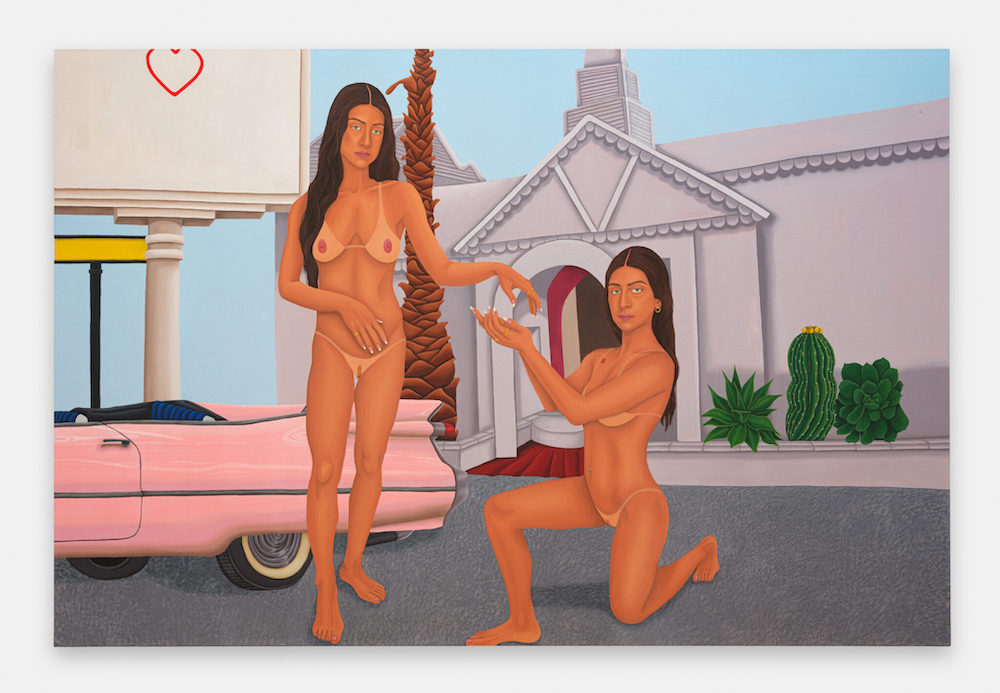

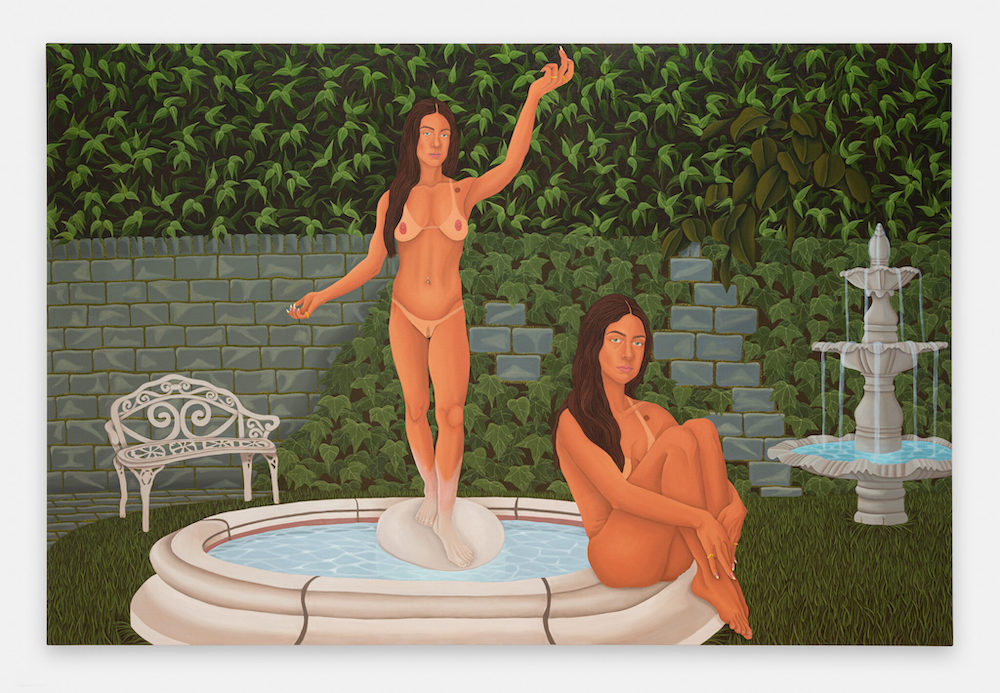

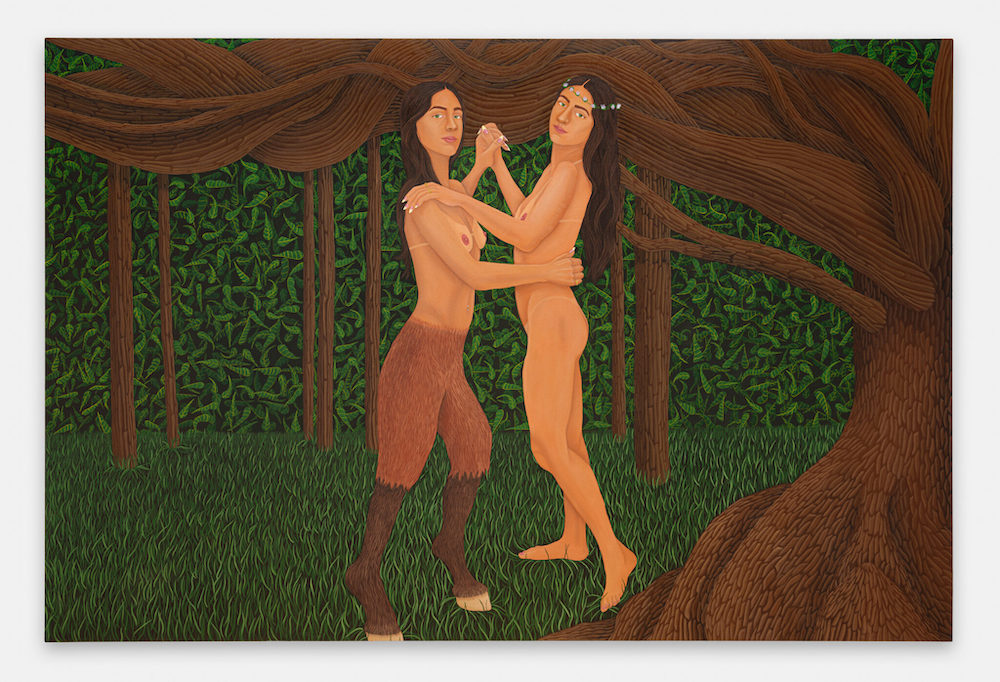

For her debut London exhibition ‘Into the Veil’, Zabinski has made a series of paintings and her first sculpture as a kind of paean to the necessary process of self-denial in addiction therapy (abstention from romantic relationships, sex, drugs, alchohol, pornography), using her fascination with familiar tropes and compositions in Italian and Dutch Early Renaissance painting, the confessional art of Tracey Emin, the deliberate flatness of Alex Katz and a loaded nod to Edouard Manet’s Olympia as touchstones in her journey towards greater painterly and self-knowledge.

The still life (abundance, mortality), over-ripe pomegranates (resurrection, everlasting life), the fountain (life, hope, water, renewal), the centaur (duality, primal drive, paradox) the dense garden (healing, learning) and classic Americana (consumption, decadence) provide the backdrop for a curiously opaque portrait of the artist.

She apparently reveals everything, at least her nudity would imply total self-exposure, but rather than baring her soul for her audience, in treating her body as a recurring motif in the delicate and complex narrative of each piece, she becomes separate from her. She is the subject, the central focus of every painting, and yet, much like Warhol’s gridded screenprints of Jackie and Marilyn, in the repetition there is little or no psychological reveal, and deliberately so. She has succeeded in absenting her real self, offering an idea of her, and of what she might be, to the spectator. She has consciously and necessarily made a painterly meme of her suffering. The real reveal, one suspects, occurs in the studio, in the making of these works, in total solitude – and therein lies their intrigue.

As Heidegger observed in his largely phenomenologically-inspired writings on the origin of art, the artwork and the artist exist in a dynamic where each appears to be a provider of the other. “Neither is without the other. Nevertheless, neither is the sole support of the other.” Art, a concept separate from both work and creator, thus exists as the source for them both. Rather than control lying with the artist, art becomes the force that uses the creator for art’s own purposes. Likewise, the resulting work must be considered in the context of the world in which it exists, not that of its artist.

That world, in the context of art, happens to be dominated at present, at least in the west, by a relentless expiation of public guilt and wringing of hands at the absence, or extremely limited presence of female artists in the institutional realm, with at least some positive results. But given the millennia of unsung female histories and experience, we have barely scratched the surface. It is no coincidence that Zabinski has chosen self-portraiture, the supposedly ‘dead’ genre that was resurrected by almost entirely by female artists in the latter part of the last century, as the vehicle to give voice to hers.

Zabinski is very aware that much of her experience is not unique to her, but all our personal traumas become our own reality, become the benchmark of what is, for each of us, our normality. As in confessional poetry, where brevity replaces lengthiness, verse exists alongside prose, meter exists alongside rhyme, Zabinski has found a free and varied visual shorthand to make her lived experience resonate through poetic means, to make the personal a reflection of the world in which we live.

That she has chosen painting as her medium to do so is apposite. Guston railed against a Greenberg-ian understanding of what painting should or could be, finding the latter’s dictat that it be only about itself both destructive and senseless. He understood that painting would always constantly reinvent itself. Artists today, thanks in no small part to Guston’s powerful legacy, have long been free of such strictures. Figuration abounds. Nothing is off limits. But for Zabinski, the intimacy of making images in painting and in portraiture specifically, the richness of inserting her own story into its ancient history, is the only way to salvation.