Terry Powers presents 14 paintings in an exhibition at the recently opened Guerrero Gallery on Verdugo Road in Los Angeles. Now based in Logan, Utah, where he is on the faculty at Utah State University, Powers is a well-known observational painter of elaborate still lifes. Most of these are of complex interior spaces, including his own painting studio; places he’s grown accustomed to in his own life and in which he is immersed on a daily basis. His paintings are ubiquitous before they are his focus, meaning they preoccupy Powers before he gives in and finally paints them. The familiarity is apparent as one considers the supple manner in which his brush renders the various scenes that seem both mundane and rich with subtle color and texture. Powers is adept at composition, yet surprisingly, he isn’t fond of staging the moments, prefering to paint things as he finds them; fearing, as representational painter and critic Fairfield Porter was apt to say, destroying the moment.

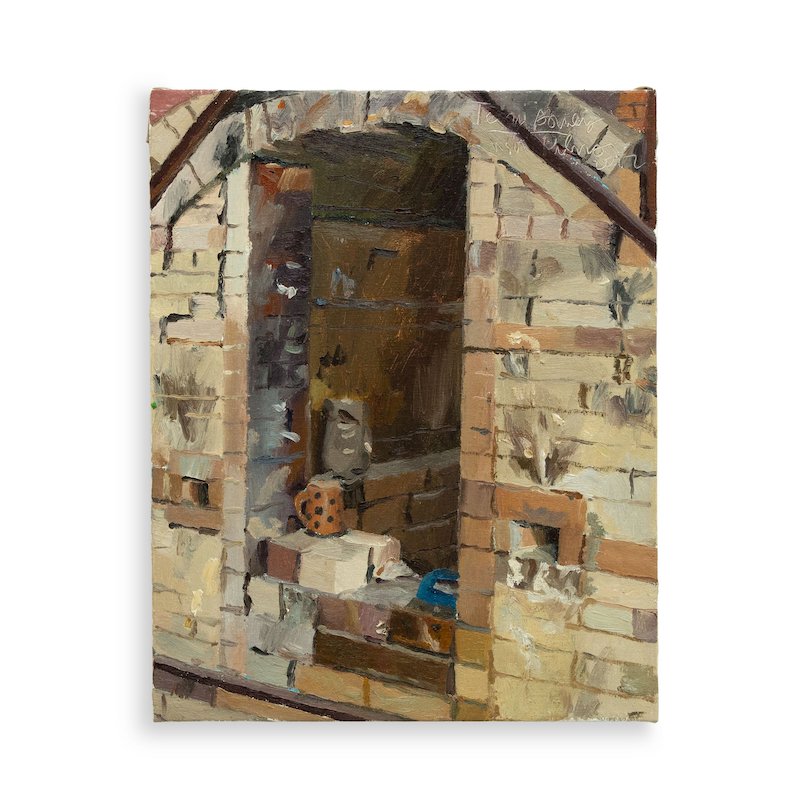

We often don’t think about it but places have distinct styles. Even American cities, younger than their European counterparts, are fertile with architectural discrepancies and seemingly heterodox colors. Utah, lush with an assortment of unique hues in the Fall, and ensconced in its own engineered lines and angles, now captures Powers’ attention and comprises his primary source material. It’s hard to paint something if Powers isn’t proximate to it, and he is relatively new to Utah. Upon his arrival less than two years ago, Powers remarked that he wasn’t used to the look of things (having grown up in the San Francisco Bay Area), yet this exhibition satisfies any doubts he may have about familiarity. These paintings document a close relationship between the artist and his subject matter.

Powers once painted on oil primed linen, but for this new body of work he’s painting on gessoed linen. Although a seemingly minor change, gesso changes the way paint sits on the surface of the picture. In effect, paint flows more easily, allowing Powers to get looser with the pigment. The paintings at Guerrero Gallery present a body of work that typifies this new gestural quality. Although photographs of the work (many circulated on social media) give the impression that Powers’ work is tighter than it actually is, viewed in person, these paintings are not strictly in the domain of realism. They are realistic insofar as they depict everyday life in a naturalistic manner, however, they do not adhere to a sharply focused, nearly photographic, style of painting — they aren’t hyper-rendered. Moreover, the smooth or blended quality one might suppose from viewing digital images of the work conceals a more complex truth, that the paintings are actually thick and rough. In part this is because linen causes the brush to drag more as it glides along the surface. This harsher texture differs, of course, from the depiction of gritty street scenes reminiscent of the 19th-century realist painters like Gustav Courbet, yet Powers does share a penchant for the unadorned and unaffected subject matter within the dictates of naturalism.

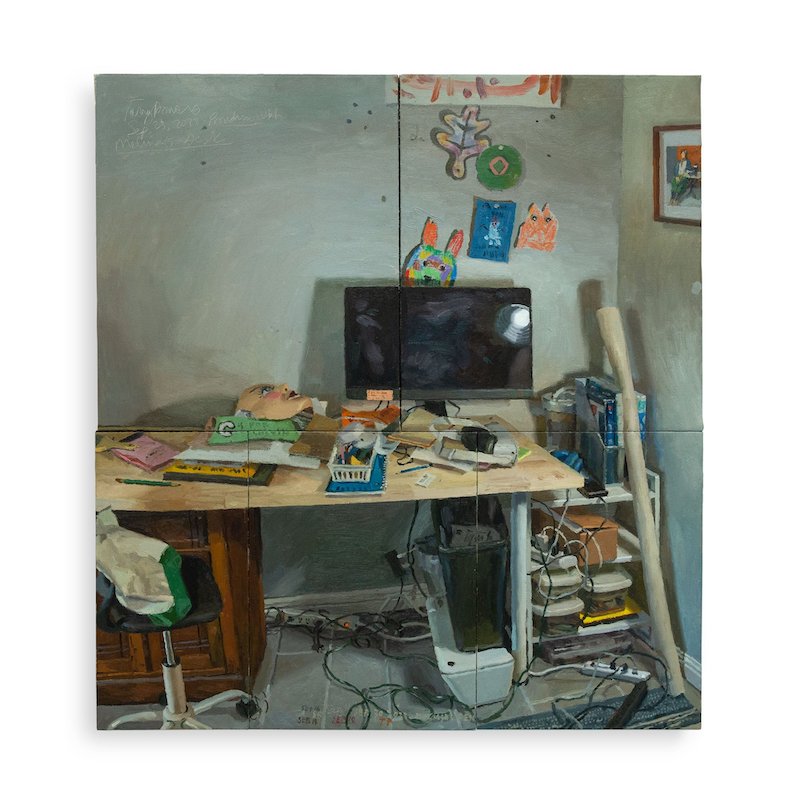

How much of what he is looking at will actually land in the painting is one of the more alluring aspects of Powers’ process. Powers begins by stretching a canvas then making preliminary compositional choices. Sometimes he becomes frustrated that he’s cropped the scene into a surface area that he later wants to expand. This is apparent in “Creeping Death,” [oil on linen, 46 x 38, 2023] where the bottom right panel of his wife Melissa’s desk, which was the first of this series of paintings he worked on, wasn’t enough to hold the growing composition of wires and objects. Without hesitation, Powers simply added panels to accommodate the growing orbit of the composition. We also see this in “Winter” [oil on linen, 40 x 36 inches, 2023] and in “Painting 4” [oil on linen, 16 x 20 inches, 2023]. The latter is particularly noteworthy as Powers brilliantly fuses two canvas segments together but purposely allows the crease line not to match up accurately. The seeming misalignment acts as an authorial comment and reminder that the viewer is looking at a subjective construct – as if Powers is saying “let’s not forget it’s a painting after all.”

This isn’t a contrivance or something he intended to do at the outset, but rather a genuine way of adjusting the composition to assuage frustration. These paneled paintings are the result. Dissatisfied with the limiting choice he had made at the outset, he pivoted toward an unconventional solution. Powers credits New Jersey-born painter Stanley Lewis for insight into breaking norms. Lewis, who paints on strips of unstretched canvas that he later glues to cardboard, will often add to it by gluing additional strips, slowly expanding the rough composition. Powers and Lewis are both solving the problem, albeit differently, of what to do when the initial choice about compositional frame is unsatisfying. By doing so, each embraces the tenant that a painting takes on a life of its own.

Powers accepts these creative impulses and rejects academic and traditional expectations. “David” [oil on linen, 16 x 20 inches, 2022] which depicts the closeup of yellow and green foliage of a tree, quintessentially the colors of fall in Utah, could strike a viewer as unfinished. Powers leaves a good portion of the bottom of the painting surface blank, except for parts of the underdrawing, which remain visible. This painting should fail. Yet, somehow Powers conveys exactly what he wants to: that he is both only going to paint what is necessary to convey the scene and that he’s unafraid to let the viewer see the process behind the painting; here, exemplified by the unfinished qualities.

Powers works with 15 to 16 colors regularly. He’ll add a couple of other green colors if working outside. He uses many different whites, including titanium and lead white. Powers emulates Spanish Baroque painter Diego Velasquez, who is known for his “long paint,” by not adding any medium to the paint, keeping the surface sticky and thick, giving it a drippy quality, as if he’s dipped his brush in a bottle of glue. Velasquez was believed to have added chalk dust in his paints to achieve this, Powers does it with various whites, including flake white replacement (made by Gamblin) which gives the surface of the painting both a starchy look to it and a long line element. The latter pigment has the added advantage of retaining translucence and warmth and doesn’t dry too fast.

Powers typically uses Isabey Special Brushes (a hog bristle brush, size 6 or 8). Curiously, he doesn’t rely on smaller brushes for the fine detailed work preferring to manipulate the larger brushes for the exacting parts. It’s as if Powers creates these challenges for himself, both to slow down the painting process, and to embrace uncertainty. How a brush is held and the way he gets the corners of the bristles to make detail suggests he’s interested in how self-imposed constraints might lead to accidents. Powers knows that in painting, failures can be interesting.

Powers often uses a split complementary palette – a kind of equipoise that utilizes the contrast and balance between warm and cool color temperatures. In this treatment, a single base color is paired with two secondary colors, rather than using a complementary color you might expect. The two colors used are chosen from a symmetrical location across from the base color on the color wheel. The secondary colors act as accents; typically resulting in a combination of one warm color being paired with two cold colors; or one cold color paired with two warm ones. One of the hallmarks of this process is that the base color doesn’t come to dominate the composition since it is offset by color wheel opposites.

He utilizes warm and cold varieties of every single primary color (red, yellow, blue). He typically stays away from earth tones and has recently been adding a variety of purples. He prefers muddy neutral tones, as opposed to earth tones (such as raw sienna and burnt umber); the latter dry faster and give a painting an 18th century feel, which Powers wants to avoid – he prefers a more contemporary sensibility and likes the painting to stay wet longer.

Ultimately it can be said that Powers is a values painter; he is endlessly fascinated by the decisionmaking around the right color and value as he places these colors next to one another. By being acutely aware of the effect this has on the eye, his focus on these color relationships are fundamentally value determinations. In many ways, Powers utilizes tonal variants to lower the contrast throughout the paintings. By doing so he reduces the saturation and dilutes the pigment. Often, he’ll thereafter reintroduce white to reignite the value changes he wants the finished painting to achieve. These delicate adjustments are what makes a Terry Powers painting. It isn’t color as much as value. This also is a way of creating focal points within the composition, as white acts as a highlighter drawing the viewer's eye to a particular area in the composition.

Most of Powers' paintings have flat light. Its dimensionality is muted which is a result of life obstacles or limitations. Powers doesn’t have a set schedule where he can always count on the same light intensity. As a result the lighting he does render is a combination of the light he’s worked with throughout the painting cycle. Gradations of value can also create depth, or the illusion of depth, and help illuminate form, thus providing needed accentuation. This is particularly true when one considers the treatment of tangents by Powers who embraces rendering whatever form he is presented with in a composition.

In geometry, a tangent is a line that touches a curved surface but which does not overlap it (cross or intersect it). Spatial arrangements can appear awkward when we see objects holding the same apparently flat space. Typically, it is believed to be more appealing to the eye to recognize spatial arrangements and have objects (shapes and lines) either in front or behind the other. When it isn’t clear, we call this visual ambiguity and the images look flat because space is collapsed into a flat plane.

Artists usually want to avoid tangents, so they create space by pushing objects forwards or backwards to present in a non-flat manner. All observational painters struggle with the question of how much to interfere with the composition. Many stage their still lifes, but then are left with a painting that feels contrived. Over time, Power has learned that the best compositional choices are found. Things that are out of place, ever so slightly, may be what conveys truth and renders the final painting more intriguing.

Connoisseurs of painting know that likable subject matter isn't important in a good painting. The more sophisticated you become at looking at paintings the more you appreciate the mundane as subject matter. What is depicted is only an excuse to render a scene with inventiveness and technical skill, be it loose or tightly rendered. Ironically, it is the peculiar objects and household appliances with cords and wires protruding everywhere that might make the most compelling picture. In this way, the ordinary becomes special. Tools and accessories are beautiful and have all the curves and angles we find in nature. Powers elevates them into something worth pondering.

Observational painting has endless surprise about it because the rendering of moments has so many possibilities. Powers, whether consciously or not, is constantly looking for paintings, knowing they are found everywhere. Navigating the world repeatedly on the lookout changes how he traverses the world. Terry Powers sees essential moments and paints what he knows. Perhaps as a result, the scene in a Powers painting always seems to have been waiting to be found. —Matt Gonzalez