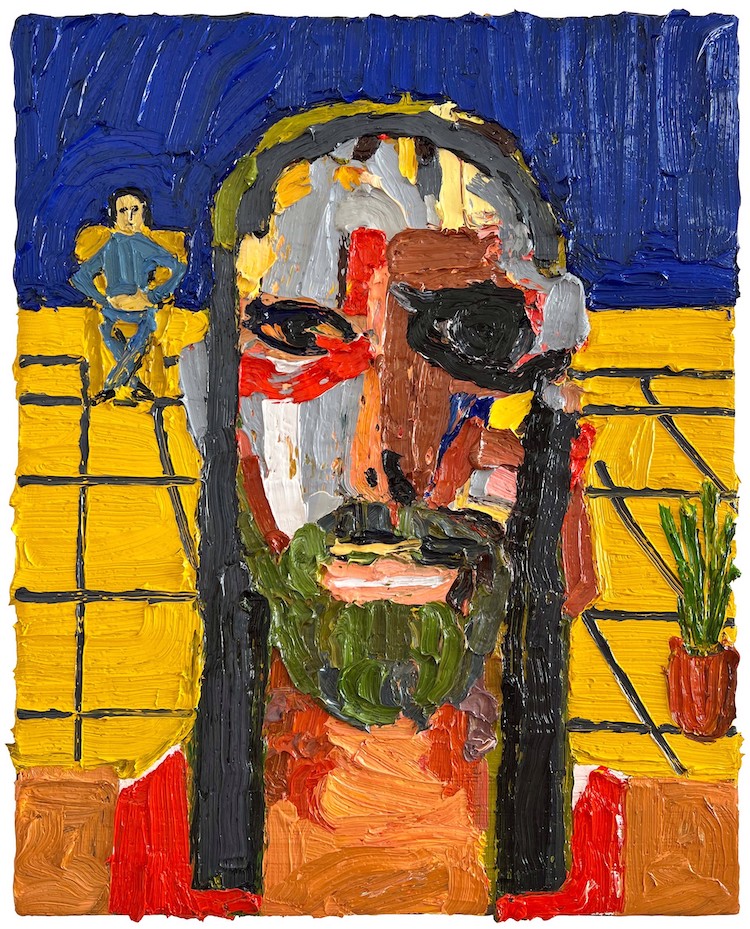

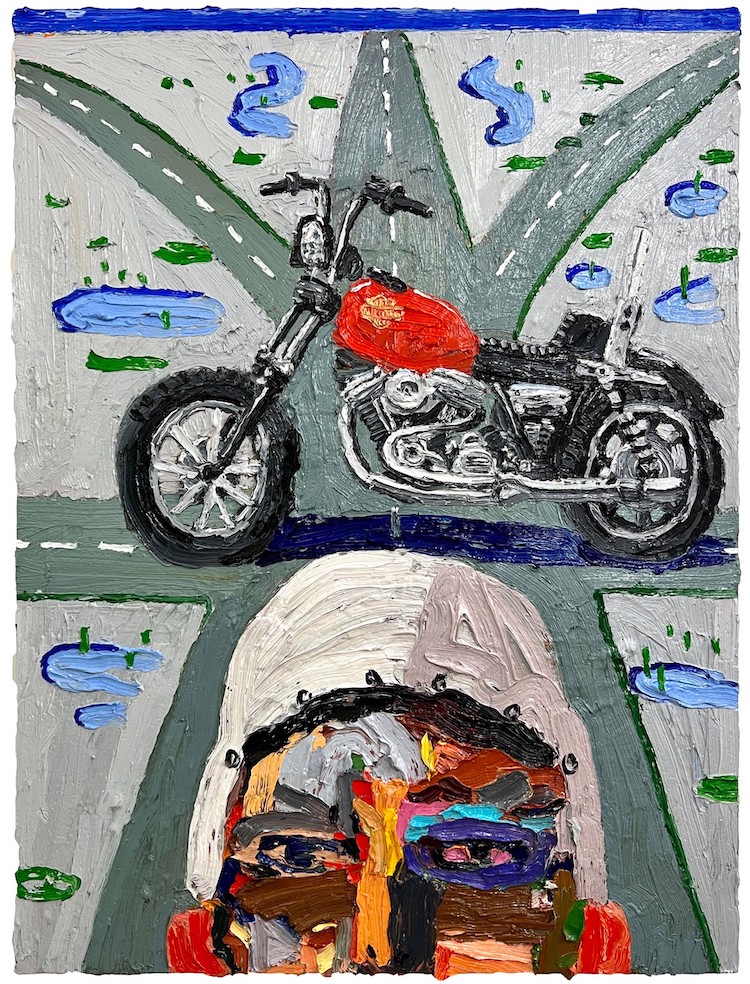

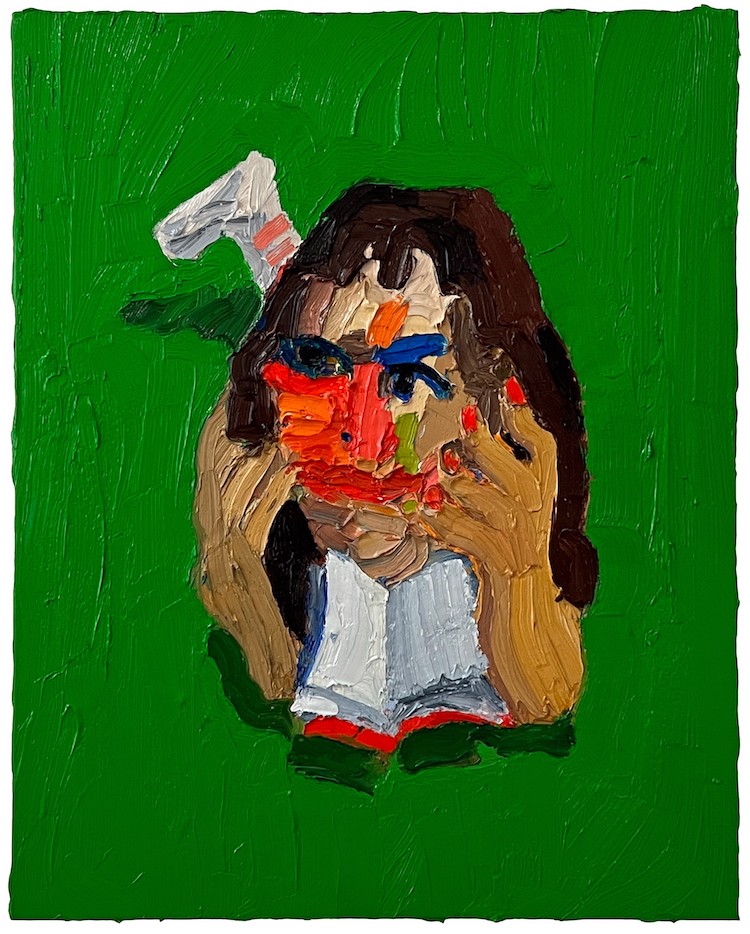

San Francisco based painter Emilio Villalba exhibits a series of twenty-five new paintings (oil on canvas works dated 2023) at Dolby Chadwick Gallery, along with a series of acrylic paintings primarily on canvas paper. Many of the works feature his wife Michelle Fernandez Villalba (a recurring subject for the artist), and various associates including his close friend Jason Crase, along with self portraits in various poses, often holding a cigarette in his hand. Sensuous qualities of thick paint characterize the body of work, revealing an artist looking for new ways to convey the human experience and its varied emotions. Many of the pictures include vernacular settings, filled with elements of domesticity and immersed with familiarity. Ordinary objects like a coffee mug, toothbrush, fixed-line telephone, and bowl of fruit are among the many things depicted.

Although painted thickly, the resulting colorful pictures explore how to render the human figure with bold gestures and deceptively simple brush work. There is an acceptance, near synthesis, of the language of abstraction, specifically Expressionism, as Villalba alternates between thick swathes of impasto and carefully considered figural and spatial design. Evincing a sense of acute presence and awareness, viewers can imagine themselves in dialogue with the various personages depicted; life-size and bold renderings are the exhibitions’ hallmark. The gestural qualities of these paintings, comprising headshots, nudes, and semi-abstract faces and torsos, is apparent. Though applied abundantly, the economy of broad brush strokes interplays with unusual perspective and lines highlighting Villalba’s painterly intentionality. The exhibition at Dolby Chadwick invokes, and is in dialogue with, the work of other artists versed in this terrain, especially David Park and Joan Brown, who both utilized impasto to make brash and confident paintings.

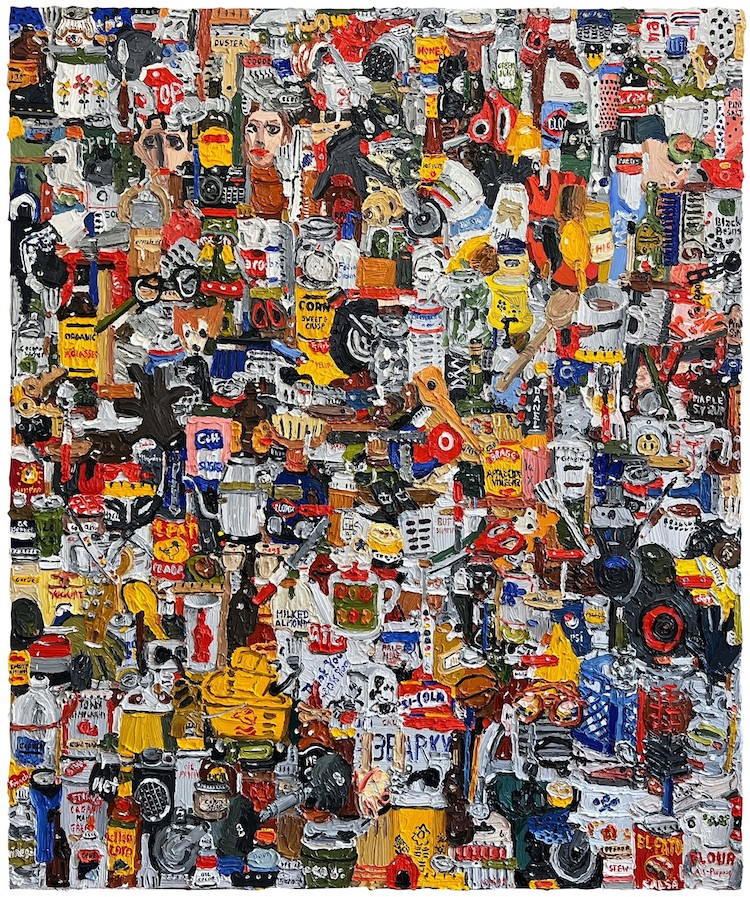

Part of the show is inspired by the living environment, in this case the North Beach neighborhood once inhabited by the beats and Bay Area figurative painters, many of whom studied or taught at the San Francisco Art Institute on Chestnut Street, including Park and Brown who were both active in the 1950s. Villalba’s view from his apartment on Stockton Street, near Washington Square Park, overlooks Lombard Hill which influenced three densely painted larger works in the exhibition. So-called “collage paintings” by Villalba are jammed packed with a multitude of objects and visages forming a seemingly crowded medley of experiences. Evoking Gerhard Richter’s series of cityscape paintings, including “Stadtbild Madrid” (Cityscape Madrid) [oil on linen, 109 x 115 inches, 1968] in the collection of the SFMOMA, presenting a flat gray-toned street and city view, Villalba has seemingly painted his own impression of Lombard Hill without resorting to the elements of traditional landscape. A hodgepodge of objects substitutes for the delineation of known urban features. The group of three paintings look as if one is viewing an apartment building split in two by a tornado, or a complex assemblage of colorful LEGO pieces; it has delightful compartments of information and visually interesting color options a viewer will easily become transfixed and enamored by. The crowded scenes, viewed carefully, show both immense detail in the articles rendered, and also approximate the visual topography the painter knows, abstracted to make a new language of landscape. Objects sit in space, sharing an equality of placement, and rely on depth, resulting in compositional harmony.

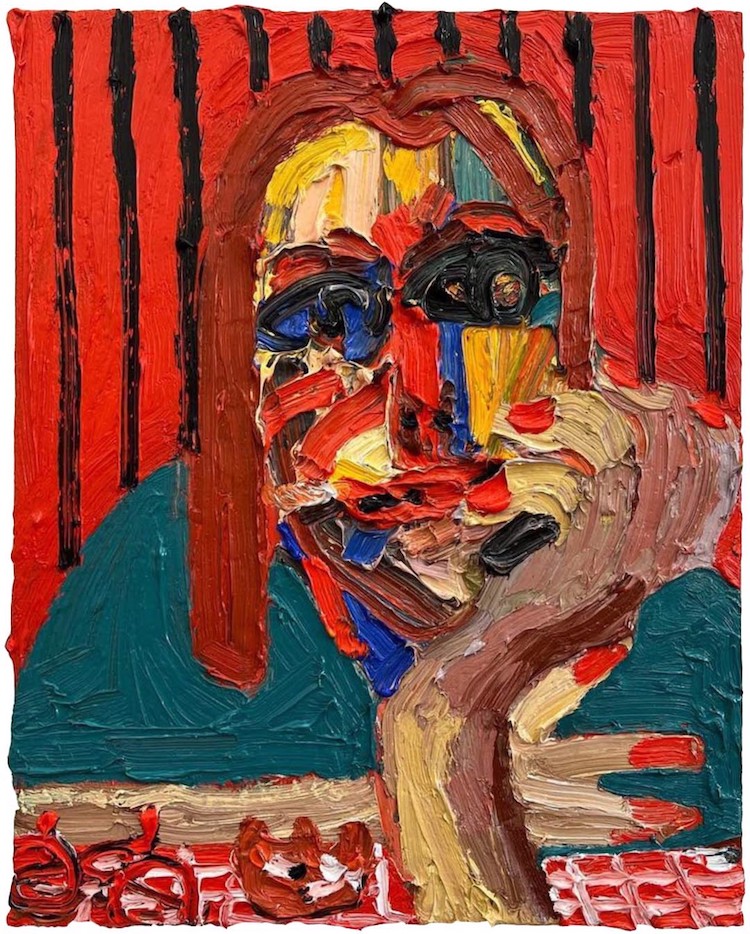

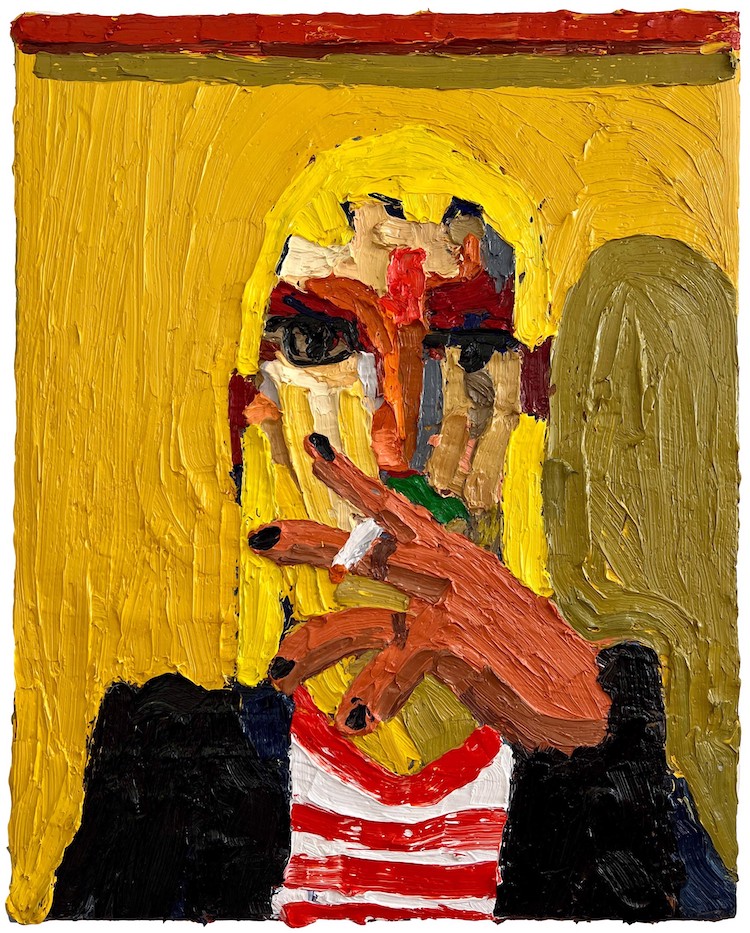

(Earlier version of "Self-Portrait (With Cigarette)")

The paintings give the impression that what you see is the result of a first pass raising the question of how exactly is the refining stage, which takes hours and multiple painting sessions, accomplished to resemble the first stage of fresh and quick impression. Looking at an early version of “Self Portrait (with Cigarette)” [Self Portrait (with Cigarette), oil on canvas, 36 x 36 inches, 2023] one is struck by how the ultimate colors making up the painting are not even present in this early draft. It reveals Villalba’s intentionality and fixation with getting the composition foundation completed first. Some clues to his method are only apparent because Villalba utilizes wet on wet techniques. Though not a predesigned picture, it is influenced by traditional action painting, with the added value that Villalba works the paint intentionally to render meaningful objects and forms. Ultimately it is the thickness of the paint that provides the necessary impetus that pushes a broad stroke painting style and its accompanying formal elements. The adage that “culture eats strategy for breakfast” applies here as Villalba embraces a Bay Area Figuration aesthetic (or culture) with the rest following suit.

Villalba’s use of negative space is noteworthy, shown through his rendering of silhouettes and in lesser instances, shadows; the use of which feels like an experiment in abstraction. A silhouette refers to an image being represented as a solid shape of a single color. But here I’m referring to silhouette as in the person or object depicted being backlit and appearing dark against a lighter background, or in Villalba’s case simply a different colored background. It emphasizes the outline of a person’s core shape. There is a sharing of silhouettes to many of the elements in the paintings as well, as Villalba encases the edges of the figures or heads in thick outlines, the prominence of both creates a strong foreground presence and also protects it from an array of brush marks colliding wet on wet with these primary features. It acts as a demarcation barrier with clear borders against whatever background exists as well. These emphasized lines are shared and act like a protective rim or barrier that sustains more than a single object.

Villalba also utilizes shadows in a way in which he transforms dark spaces into shapes rather than just a platform in which to place nearby a person or object. Shadows ultimately can be placed where they don’t exactly belong, and in shapes lending to some allowances, furthering the painting illusion. [e.g., Self-Portrait Beneath a Window, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches, 2023; and, Self Portrait with Model, oil on canvas, 36 x 36 inches, 2023]. In other cases, the shadow is ignored altogether. [e.g., In Conversation with Jason, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches, 2023; and, Michelle with Groceries, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches, 2023]. Philip Guston is one artist who often left shadows in his paintings working in opposite directions, meaning there were probably competing and multiple light sources presented simultaneously. Villalba embraces the shared understanding that shadow needn’t be rendered truthfully, it doesn’t have to act as if in nature to be used for its own artistic elements. Bay Area Figurative painter Paul Wonner once acknowledged this, saying “Eventually I realized that I could connect compositional elements with shadows. People thought that was strange, because the shadows were doing things that they couldn’t do naturally.”

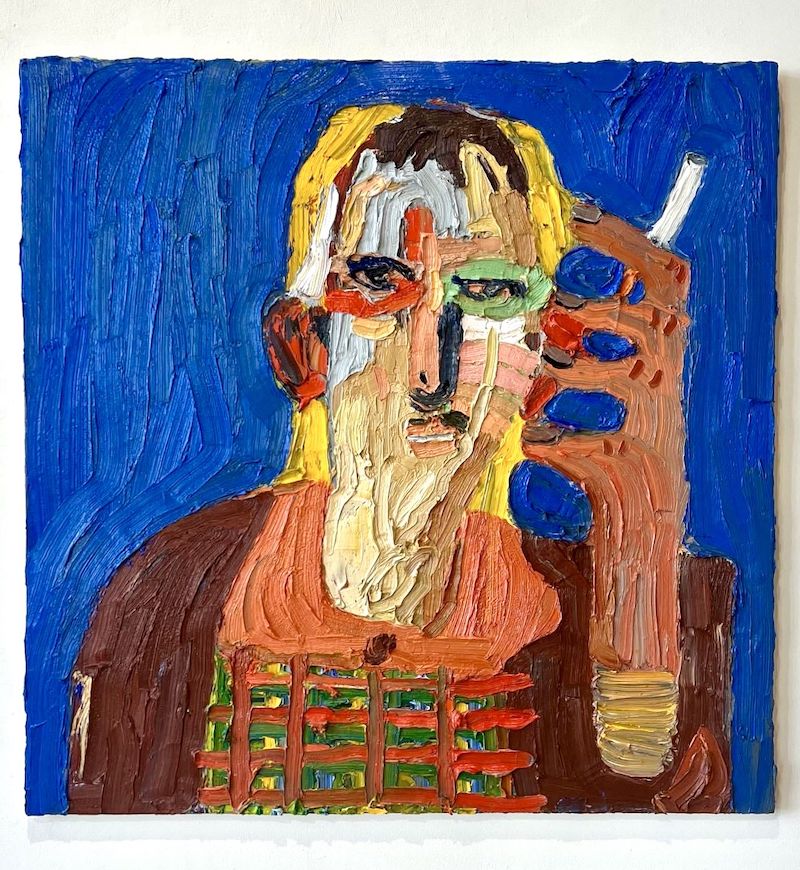

In “Self-Portrait (with Cigarette)” Villalba offers a bold visage of himself looking intently at the viewer, cigarette in hand, as if in conversation or as if carefully examining the examiner. A rich, bright blue engulfs the background with a series of blue splotches of paint running along the painter's left hand. Meant to delineate the space between the fingers (and the gap above the shoulder meeting the cigarette-holding hand), and matching the color of the background, the element is wonderfully clunky in its execution. Although they’re apparently not very subtle brush strokes they importantly add a defining expressionist element that emits power and confidence through raw thickness of the paint. It also delays visual understanding by viewers who will grapple to make sense of what is being seen compositionally. Those blue marks could just as easily be topaz or sapphire gemstones or boldly painted bright blue fingernails thus, both complicating and enriching the key features of the picture.

Further evaluation of this painting reveals Villalba’s method. The foreground and lower torso of the subject is dominated by seemingly parallel cross-hatching of brush strokes, creating a basket-weave breastplate element that most likely is a plaid shirt, atop another pink garment, both partially visible beneath a brown jacket. The figure’s neck is slightly turning with just enough pigment variation to capture the various veins and muscles there. Meanwhile, the self-portrait’s silhouette acts like a protective helmet over the subject’s head painted with a bold outline. Looking at the meandering vertical space from the figure’s index finger downward along the silhouette line, one sees the blue hitting the yellow of hair, which bleeds into the collar of the shirt. There is an “S” shaped design going downward meeting the shirt with various colors pushing up against the silhouette border. The edges may be slightly broken because of wet on wet application but mostly the key features remain discernible. By contrast the field within the silhouette outline is filled with dynamic paint variation. Here is where symmetry would be expected, but Villalba ignores that value prefering to vary the facial presentation, making it dynamic and allowing a viewer's eye to explore many variabilities.

(Final version of "Self-Portrait (With Cigarette)")

The face in this painting has a vertical, yellow element along the left cheek which seems as if it should be disruptive or at least distracting. It’s not a tear (depicting crying) but catches the eye because the brush stroke is counter to everything around it. In many of the paintings, this one included, Villalba purposely offers asymmetrical renderings of human faces. He seems to make an imaginary vertical split along the center of the head with each side being unequal and containing different brush marks and color combinations. In “Self Portrait (with Cigarette)” the rendering of different colored eyes (pink/orange and green) is striking even though lopsided. This is also present in “Tiny Portrait” and “Michelle at the Cafe” [Tiny Portrait, oil on canvas, 6 x 4 inches, 2023; and Michelle at the Cafe, oil on canvas, 20 x 16 inches, 2023]. It is this very abandonment of symmetry in the painting of faces which helps infuse the images with movement and consciousness, and allows the viewer to peruse the composition longer because there is so much to see here.

The boldness of this exhibition reflects Villalba’s changing palette. Once an adherent of the Zorn palette, used by Swedish portrait painter Anders Zorn, which eschewed blue and utilized only four colors: black, white, red, and yellow (ochre originally), Villalba has shifted to what he calls a Mondrian palette (after De Stijl painter Piet Mondrian) which is in effect the primarily color spectrum. The paints are often straight out of the tube with mixing happening as he paints wet on wet. The bristle brushes he used allow him to load up the paint for each stroke. It’s worth noting that while many artists work with heavy impasto utilizing a palette knife and waiting for paint to dry, Villalba does it all with brush, happening wet on wet, with no added medium. The lusciousness that results from layering the thick paint is enticing as if the viewer were examining the icing on a cake; literally making the paintings look like you could stick your finger into them.

Villalba is obviously attracted to loose painting but it would be too simple to stop there. He is a highly formal painter who is likewise drawn to spatial organization in his paintings. As much as one sees a Bay Area Figuration or German Expressionism influence, Villalba is also indebted to the compartmentalization framework of artists such as Mondrian. Expressive brush strokes coexist with compositional forms highly attuned to depth, object placement, and perspective; all of which Villalba nonetheless sometimes consciously deviates from.

This is an important show. Although Villalba makes painting look easy these paintings are intentional in both color application and compositional arrangement. One of his gifts is managing to embrace the techniques of gestural painting while controlling the picture plane. He invites a re-engagement with Bay Area Figuration and makes a compelling statement about its new possibilities. —Matt Gonzalez