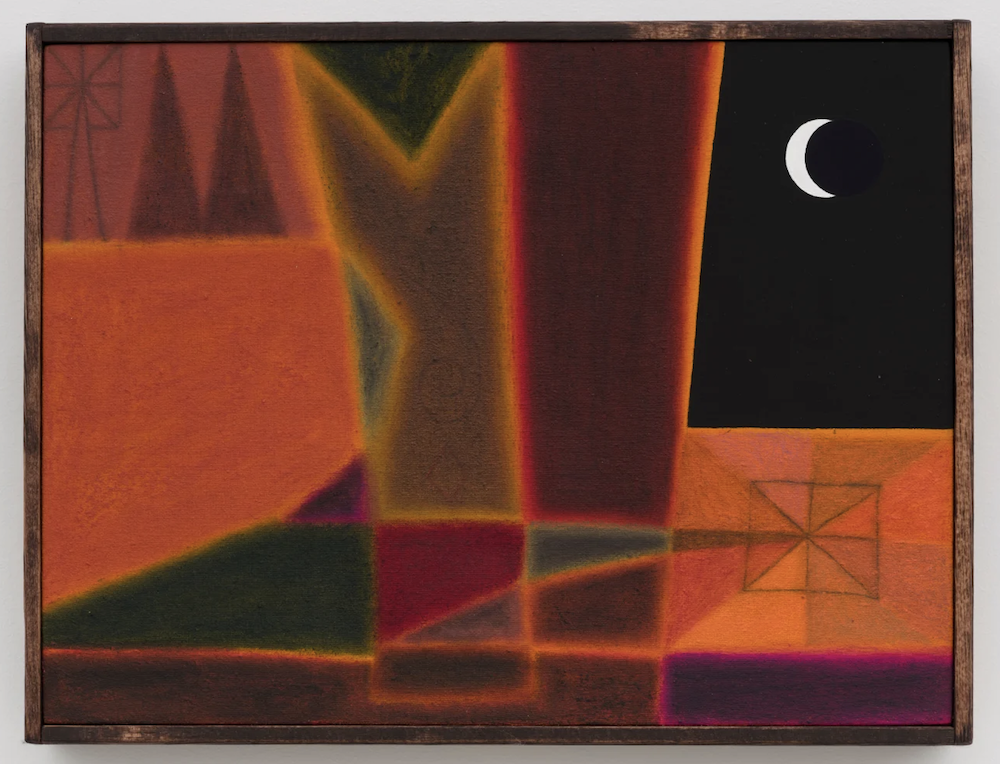

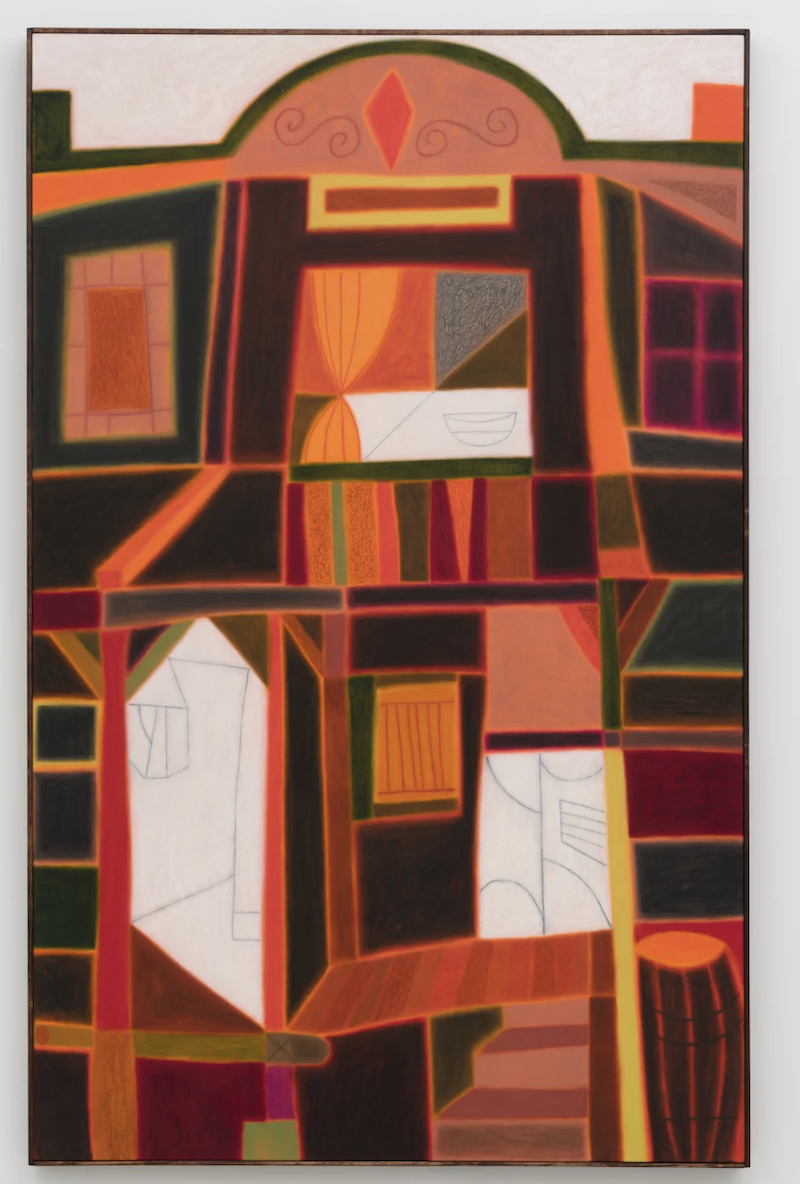

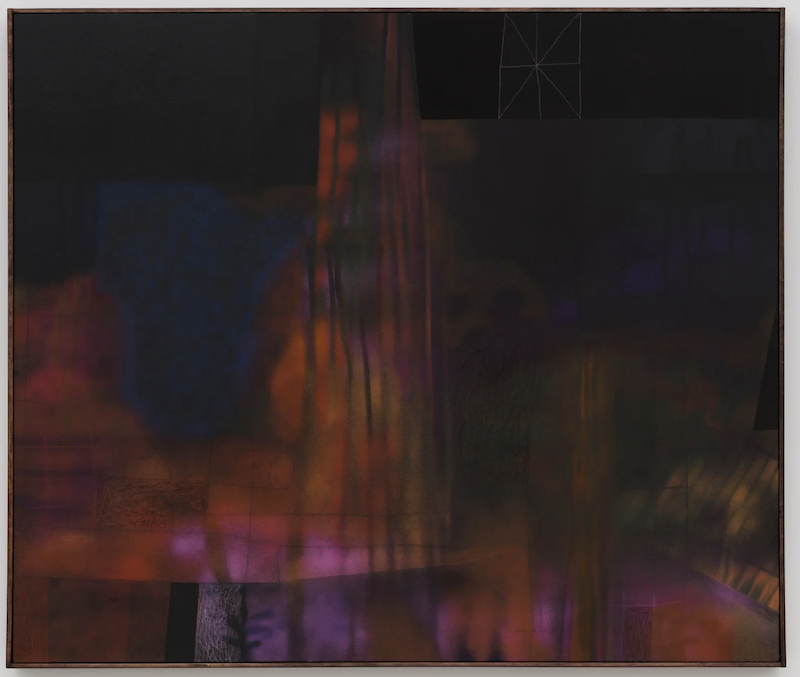

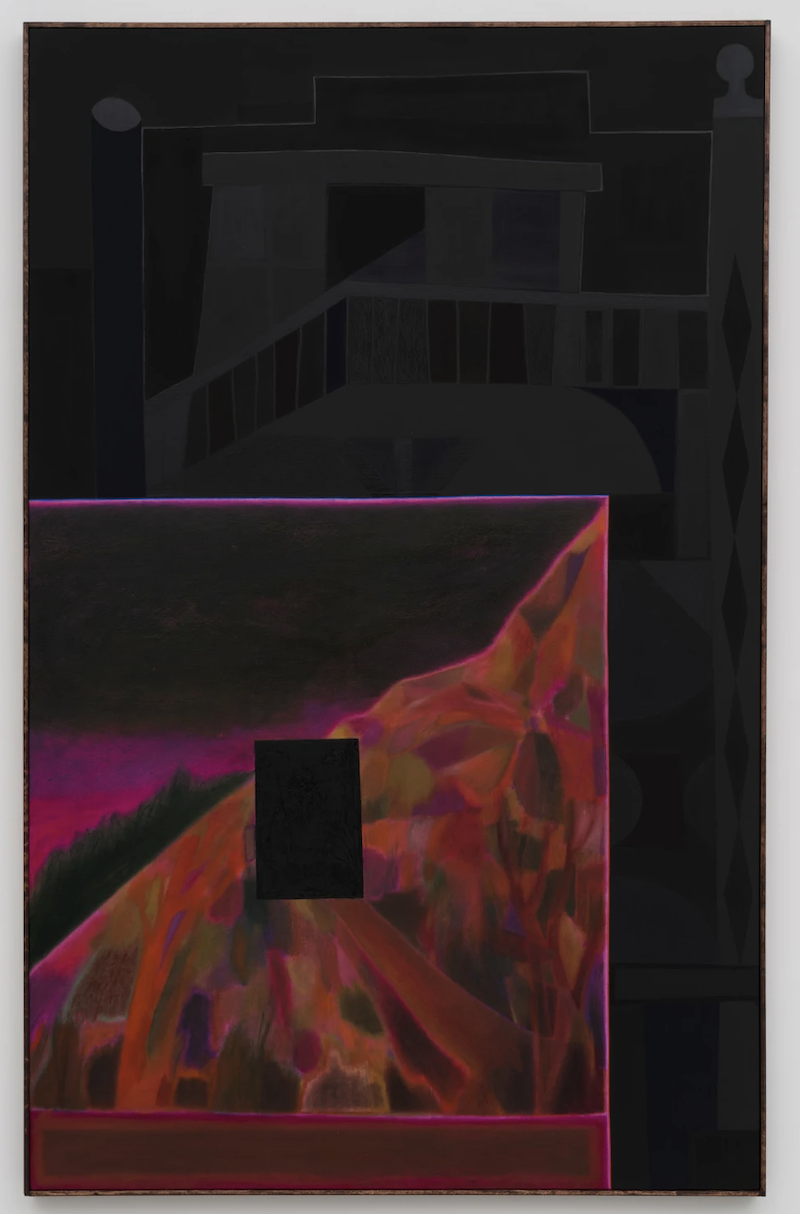

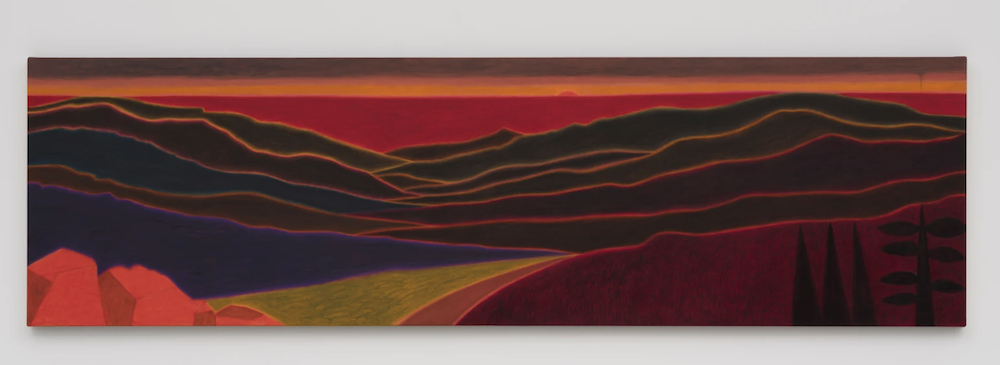

Philip Martin Gallery is pleased to present, The Breeze and I, a solo exhibition of new paintings by Oakland-based artist Muzae Sesay. Sesay’s exhibition moves in cinematic glimpses, one step behind an unnamed Black cowboy moving across a Western landscape. “Even in my desolation, I maintain a restless fire for chasing the sunset west.”

The Breeze and I: Self Negotiation

A transcribed conversation with Muzae Sesay

“The Breeze and I” is the first time I have centered a fictional narrative in the work. All the paintings in “The Breeze and I” depict the world of a fictional unnamed Black cowboy, freed from slavery, moving westward towards the promise of nothing. My idea of centering the work around the life and environment of a Black cowboy stems from 2016-17, when I first discovered the existence of Black cowboys.

Having always been fascinated by cowboys growing up, I started doing research. In Southern California where I grew up there are a lot of Western relics. There is also a strong presence of Native Americans, and a sense of missing complexity in the Western story as told in American culture. I was taught a character who represented a rugged, lone ranger archetype. However, I also felt that the cowboy and cowboy culture itself was so removed from Blackness. I did not relate to that, or feel that I had permission to relate to the cowboy. When I found out that 25 percent of cowboys were Black, and that the term ‘cowboy’ itself is originally a Black term, it spiraled into my seemingly lifelong intrigue in Black cowboys.

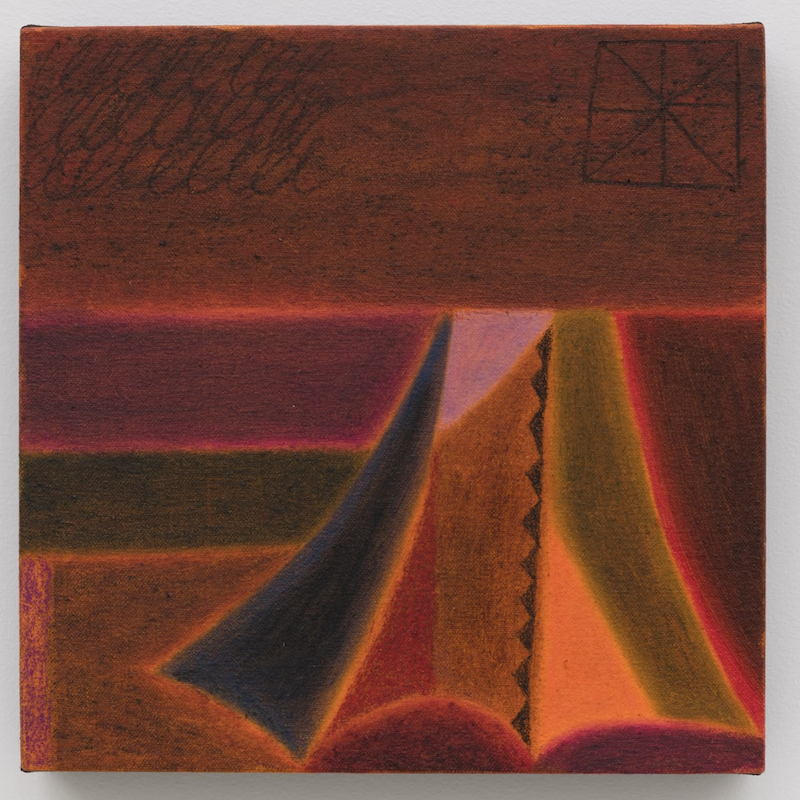

I have conceptualized this for a while and have done both drawings and smaller paintings within this realm. This is the first time I am really doing a full exhibition. It has been quite a charming experience, making fictional work as opposed to responding to the more socio-analytical theory that sparks my other types of paintings. While making this work, I built a connection with the character’s untold story. Although I gave him so much personality in my mind, he remained nameless and unexpressive in the work, a mystery that for me reflected actual stories of Black cowboys. Their stories are often mysterious, verbally passed-down, or eliminated. There are not that many photos or images either. What are their stories? That opened up the world for me - the possibility of stories.

When I imagine the actual stories of these Black pioneers, there is extreme isolation, loneliness, resilience, self-determination and perseverance in the face of a violent world. In my mind, the character is an amoral anti-hero that straddles the line between love and hate, hopeful and uncertain - shrouded in turbulence - with a willingness to live beyond any logical reason: the illogical inherent human optimism to survive under any circumstances. Maybe our minds have gone - given up on the world, society or something - but our bodies still push forward. It illustrates the optimism and progressive nature of humans in general.

Without being directly figurative, the protagonist in the work is present, but missing. I wanted to stay true to the nature of my practice, and provide a space for viewers without a figure. It was quite an interesting experience to create a fictional narrative with no character present. You have to put together the pieces to even infer this character - similar to the type of research you have to do when you are looking for these stories throughout history. You have to put together these missing pieces like a puzzle. The viewer is meant to traverse the world as if following the cowboy’s trail. Close but always steps behind - painting by painting, piecing together a puzzle. In a sense, it becomes a parallel act to the attempts to find the real-world stories of the Black cowboy that were eliminated by the white cowboy Westerns of the 40s and 50s, and only passed down verbally.

Keeping the protagonist nameless and mysterious allows him to represent an endless amount of untold stories - putting that agency on the viewer to define. The idea of what they had to go through is presented through their hopefulness. The paintings straddle that line between nihilism and optimism, pointing to the amorality of the character and the amorality of the situation that they were in - having to kill or be killed. Having to survive or die. It seems very transactional. The uncertainty of me, the creator, is also reflected in the stories themselves, and the imagination that we are forced to have when thinking about these characters. When faced with that forced imagination, I say - OK, I will imagine this - I will make the story and create the possibility in my own mind of what this person might have had to go through.

I think about this show as episodic, and in that way, really relating to the Western cinema. There is this Western cinema aspect that I want to bring to the show. In quite a subtle way, I think, like most motifs and ideas. There is a bit of subtlety in the exploration of everything. I would like to add this subtle homage to cinema and a reclamation of Black cowboys being in that cinematic space. This goes into the aspect of the Western, too, and how at the time, the white American narrative idea of basically completely erasing any idea of the Black cowboy, taking the name ‘cowboy,’ reappropriating it to be white, and to using it to describe the John Waynes of the world. That act itself is just the death of all of those Black characters. That is why this becomes so forced into the imaginary. The ruggedness that was that character was taken. It is a parallel that happened in Black culture. Through adversity, through pain and suffering, the Black community makes something beautiful, or makes something cool, or edgy, or interesting, or on the vanguard of society. A hegemonic society then sees that, and says, ‘Thanks! We’re going to take that, commercialize that, and erase your stories completely.’

I think this is a thing that has been indicative over time, and it is interesting to see it play out in this realm. While I learned about the Black cowboys, it opened up a whole new realm of thought. This could have been playing out over history - the same thing that happened to rap music, is the same thing that has happened to the idea of the cowboy, and the Black Western, or Black people’s involvement in music, in folk music and country - and all of the stylistic aspects that come with that. It opens up this world to wonder how many other communities this has happened to throughout history. What about Native Americans? It even moves beyond the Black cowboy, to think about societies in ancient Africa and the Middle East and communities in Europe that might have been eliminated and their stories erased.

“The Breeze and I” is on view through December 16, 2023