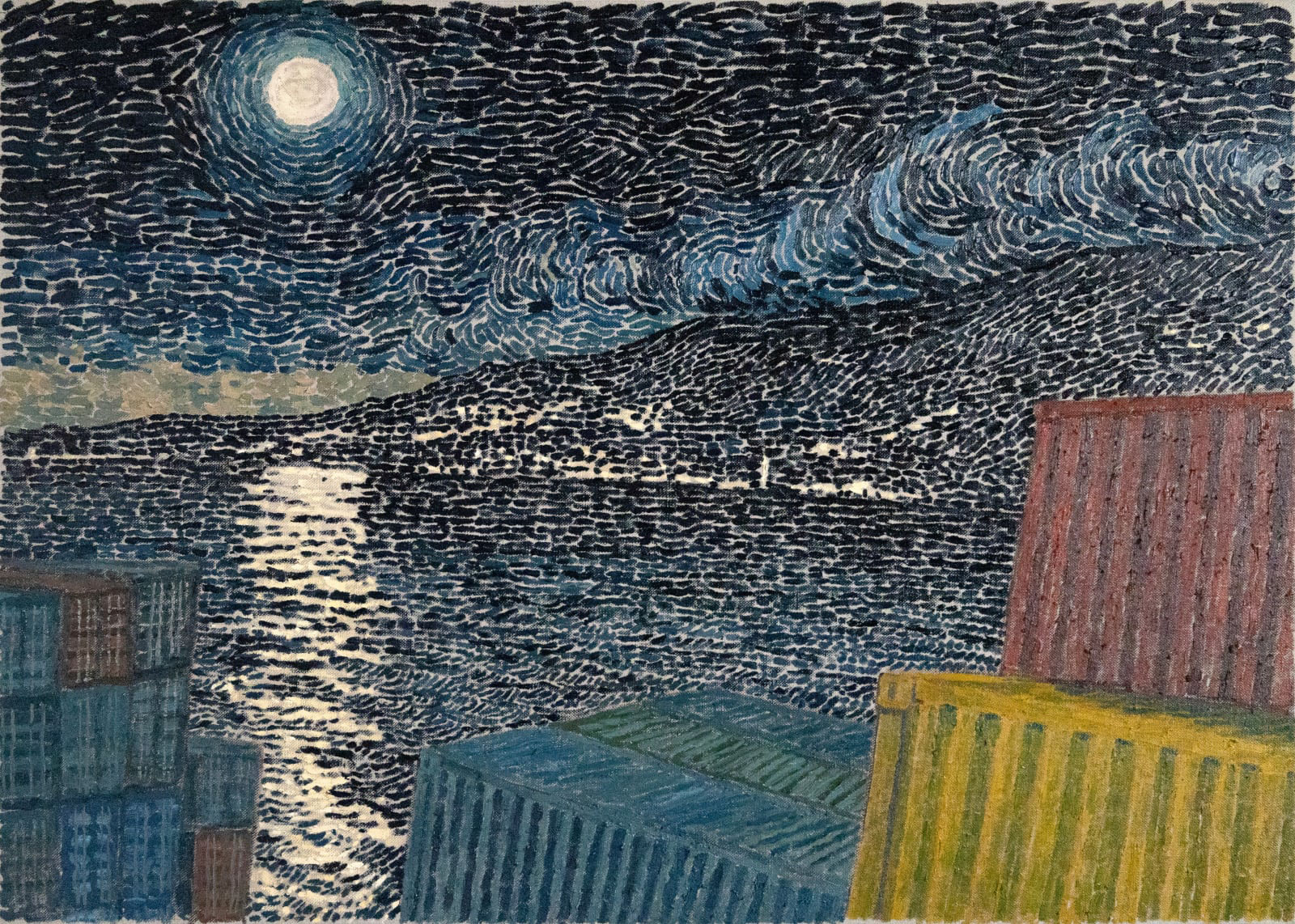

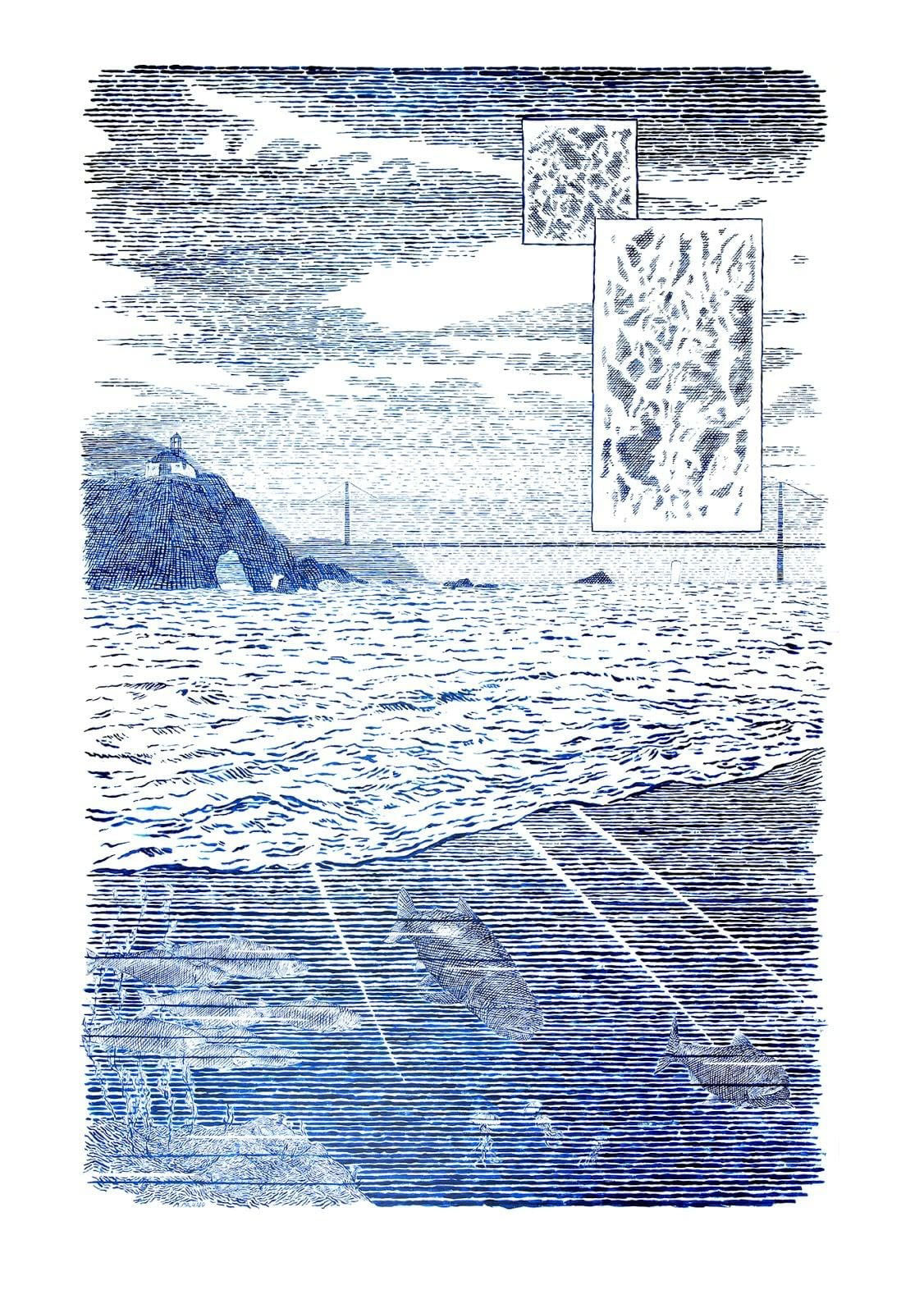

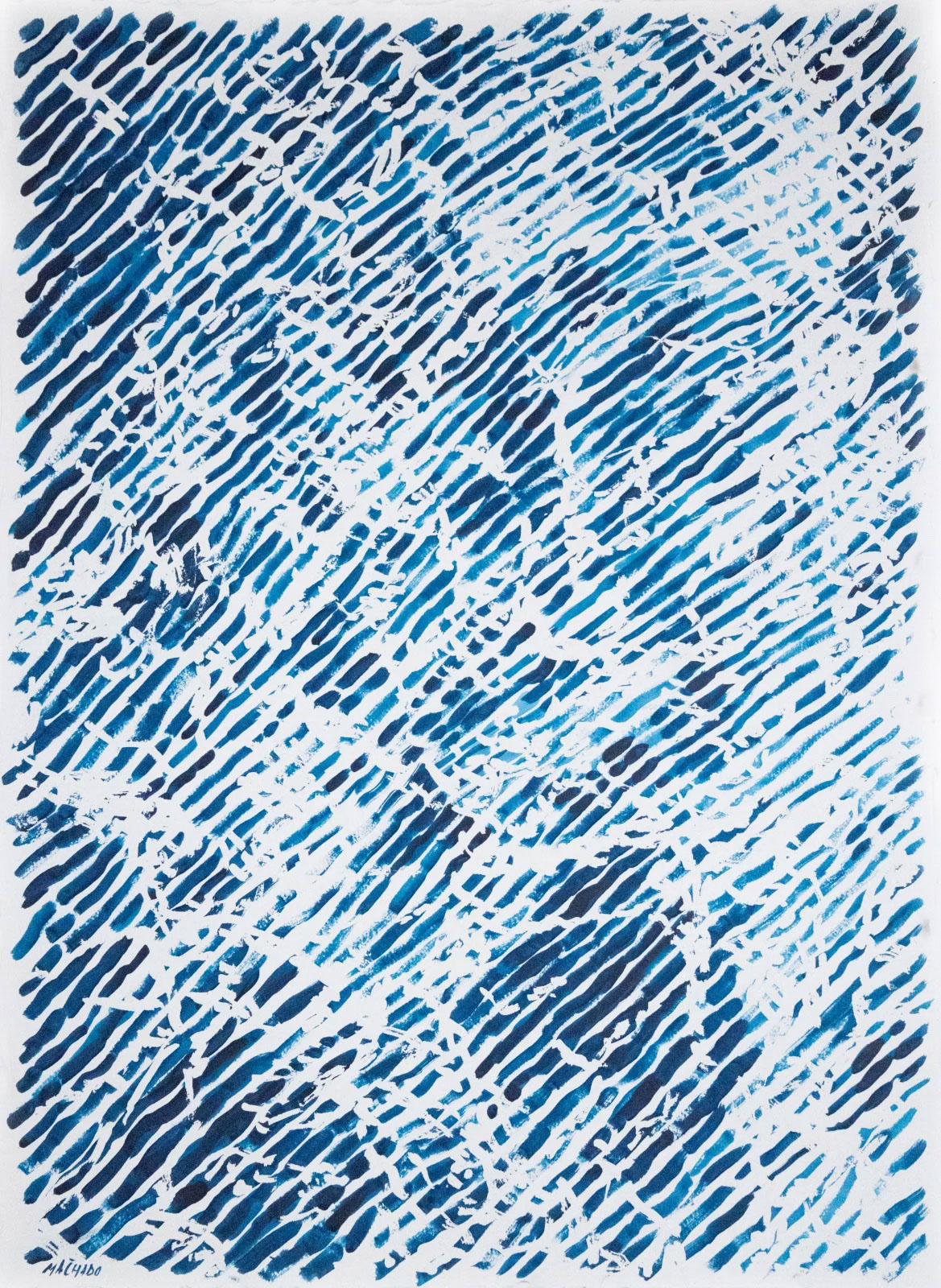

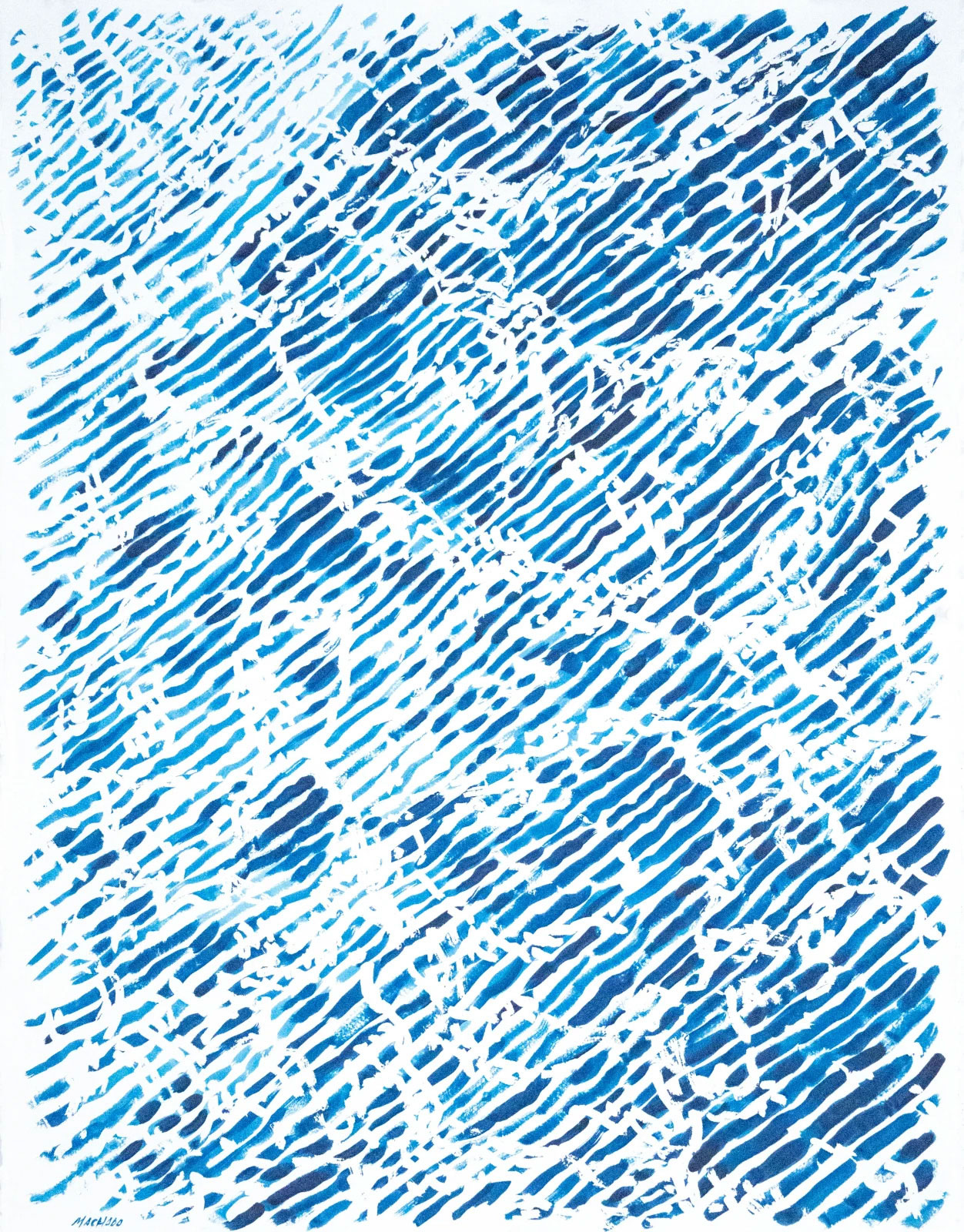

Martin Machado celebrates what he calls “natural intelligence,” a direct response to a city abuzz about artificial-intelligence, his artistic work represents nature’s slow cycles and seasons. For over two decades Martin has earned the bulk of his income from the sea, working as sailor, commercial fisherman, and merchant mariner. From international containerships to small fishing skiffs in Alaska, the ports and people he has worked with are intertwined with the paintings he makes. It is a visual story-telling of both his experiences and our core human connections with the sea.

In recent years, as Machado’s commercial salmon fishing season comes to a close in Alaska, he returns home to Northern California and begins another sort of harvest. Along with friends, he picks apples and other pommes from wild and feral trees scattered throughout the greater Bay Area. This fruit is then macerated and pressed into juice, poured into barrels, and left for nature to continue its course through fermentation. With little to no intervention, it is guided from the tree to the bottle and the results tell a story through its taste and texture. Sharing the cider with others is part of the reward that keeps him foraging and planting new trees for future seasons and generations to come.

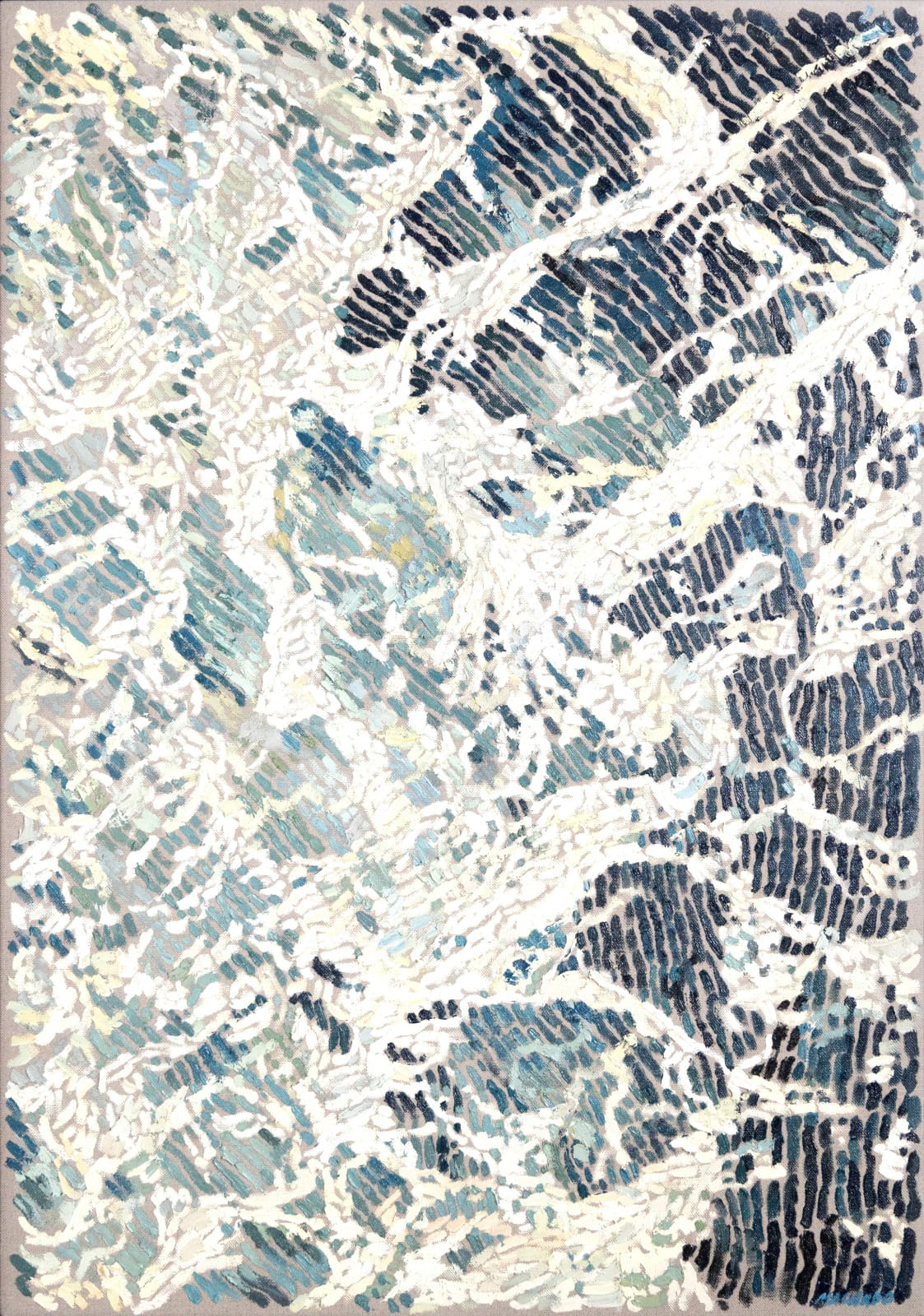

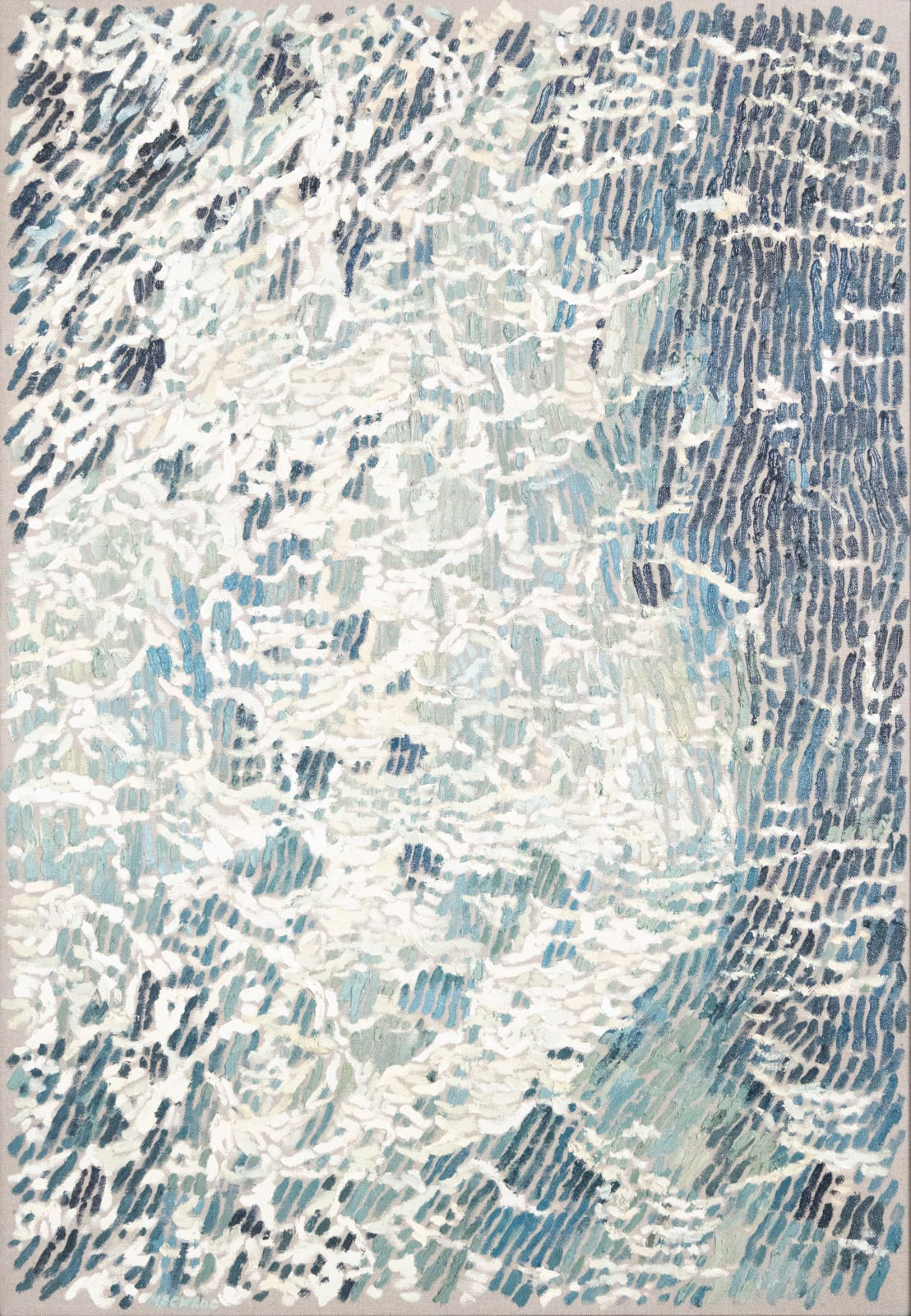

The style and subject matter of Machado’s artworks harken back to adventurous artists that came before: the post-impressionist markings of a wandering Van Gogh and Gauguin, or the expansive compositions of Hiroshige’s woodblock prints. However while his subjects may be timeless, the contemporary environmental threat to them is very real. The wild salmon runs that he fishes in Alaska are under constant attack by strip mine prospectors proposing to exploit the very ground beneath where the salmon spawn upriver. The oldest of nearby apple orchards, capable of being dry-farmed and surviving the climate whiplash that is our new normal, are being pulled out each year as wealthy landowners plant vanity vineyards that require the extremes of conventional agricultural practices to keep them alive.

The title Three Sheets To The Wind, Out On A Limb is a tongue-in-cheek acknowledgment of just how perilous our contemporary situation is. However, the works themselves are meant to be a sign of hope and awe, of the resilient yeasts that wake up to finish their work when winter thaws, of the spiraling ocean currents that carry nutrients to the surface from the darkest of places.