“The more you know your own history, the more liberated you are.” Spoken by the eminent poet Maya Angelou in 2012, this lucid, hopeful phrase also communicates an age-old hurt. Since the earliest experiences of migration and exile, how many people have lived or are living filled with a need to discover their origins in order to reclaim a past their adopted land has deprived them of? Like the aforementioned writer, who died eight years ago; or the historian John Henry Clarke, who in the early 20th century likened the relationship of an individual to their heritage to that of a child to its mother; many African Americans have set out in search of their ancestry to fill the gaps in a narrative punctured by upheaval in order to better understand themselves. In his case, Marcus Brutus has chosen to paint.

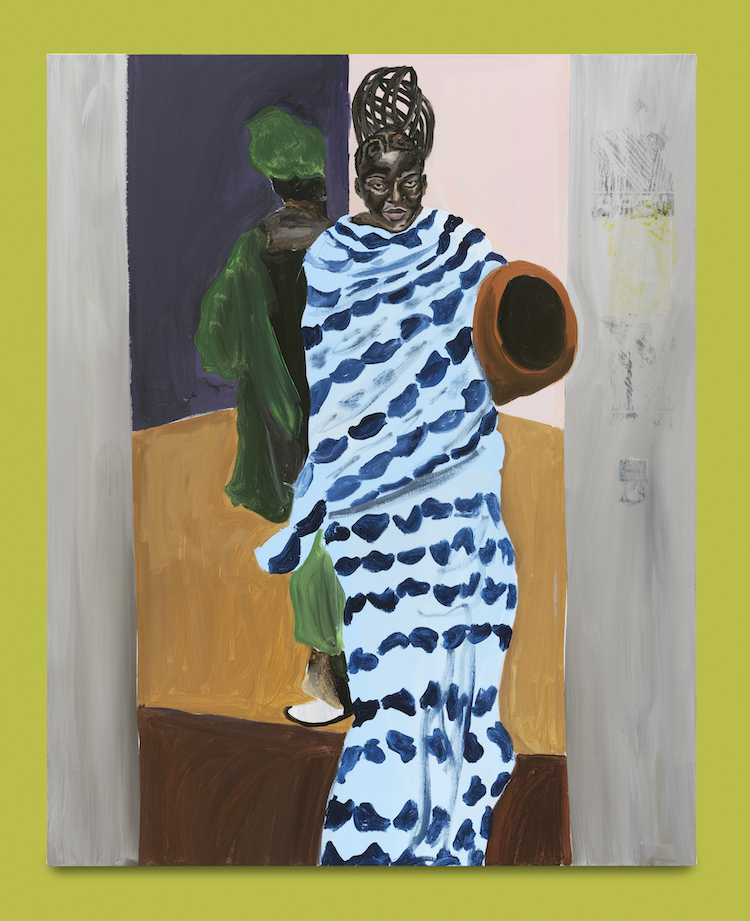

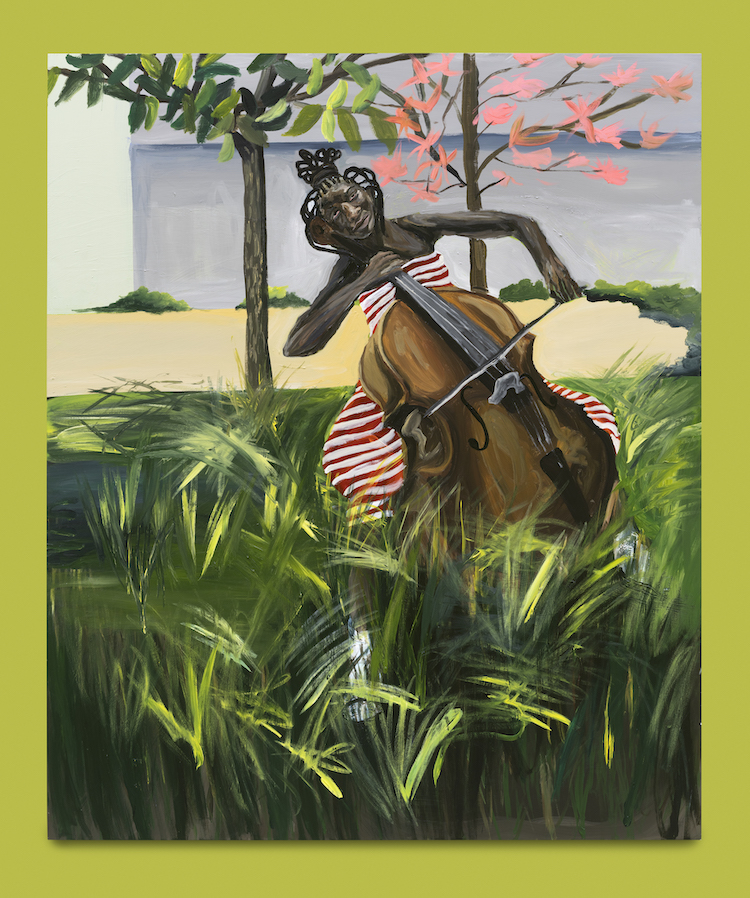

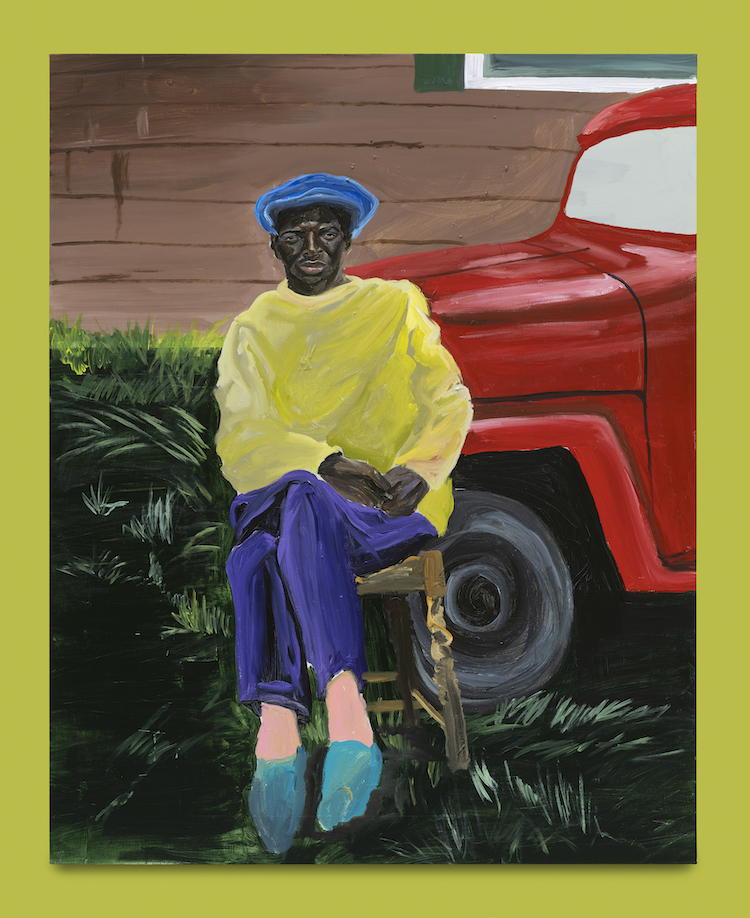

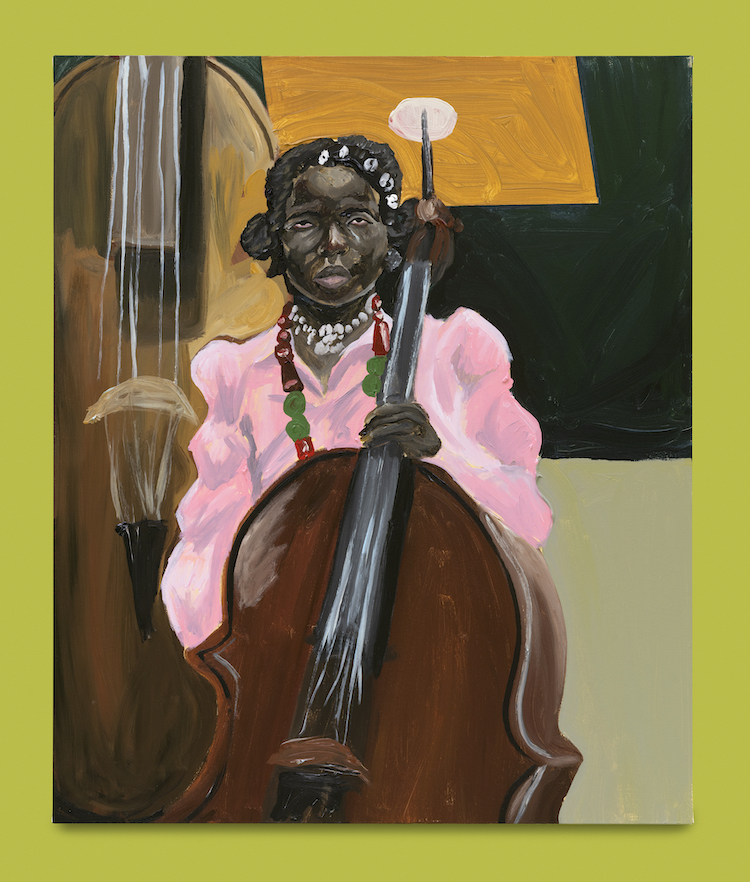

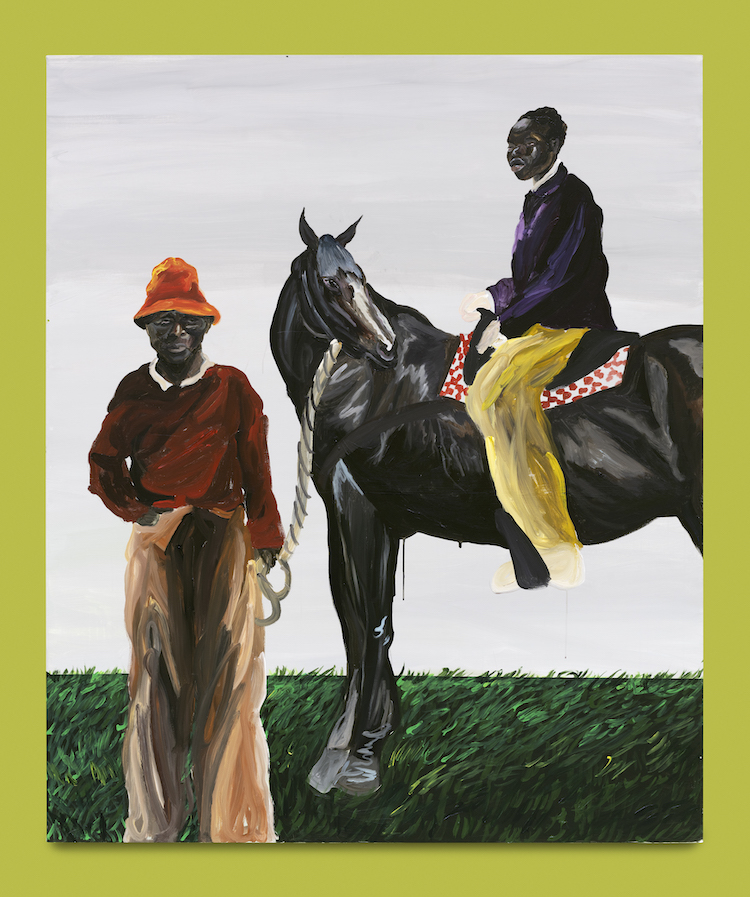

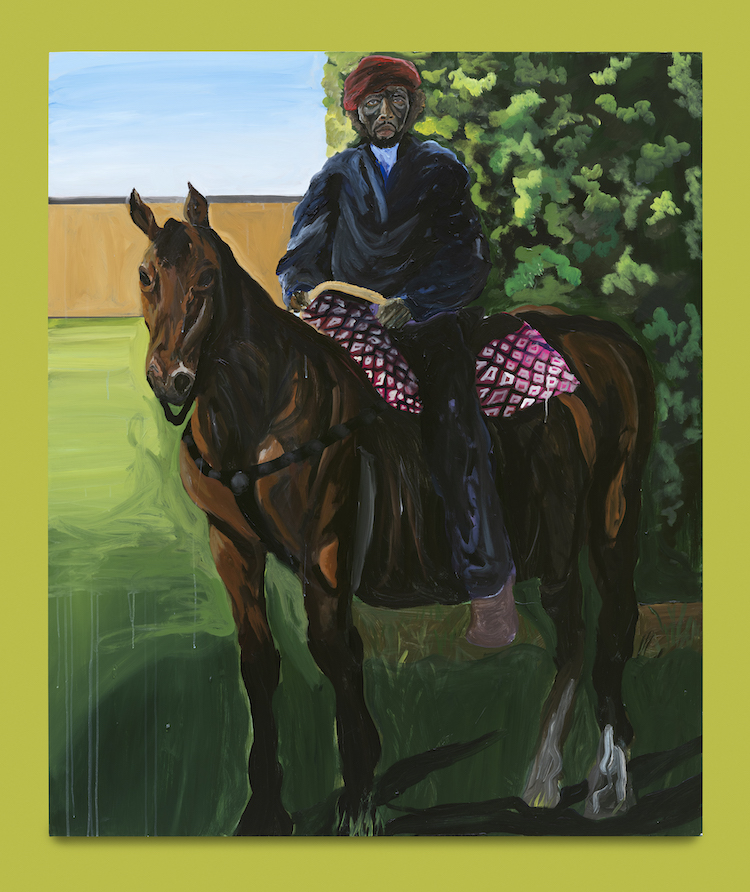

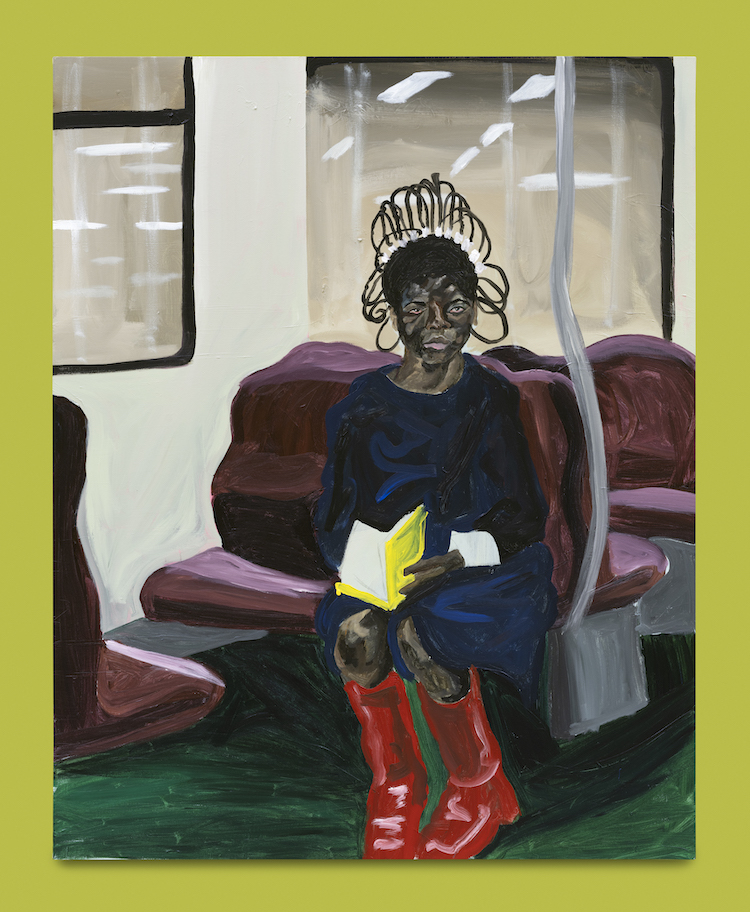

Born in 1991, the artist of Haitian origin is part of a generation of descendents of immigrants who have only ever lived in the United States but have adopted the habits and customs of their heritage at home. It is a multicultural context that, despite its richness, can also disrupt the formation of one’s identity. Where other immigrant artists summon very personal stories in their work, the more or less distant curiosity for his roots between Haiti and Senegal has become the young man’s creative engine. Since the beginning of his pictorial practice ten years ago, the Washington D.C.-born artist’s approach seeks to pick up the pieces, both figuratively and literally. Mirroring this process, his figurative paintings draw from a vast library of images that he has instinctively collected for years, regularly adding elements here and there. Under Brutus’ brush, a Caucasian cellist taken from a recent film scene is transformed into a young black woman adorned with a traditional African hairstyle and a fuchsia blouse. In another painting, the perfectly trimmed garden hedges from a high-end fashion campaign become the backdrop for a scene in which a beret-wearing character rides a horse. A result of a childhood spent with his mother and sister, the hairstyle has become an object of particular attention in Marcus Brutus’ works, the fruit of his numerous historical and anthropological discoveries.

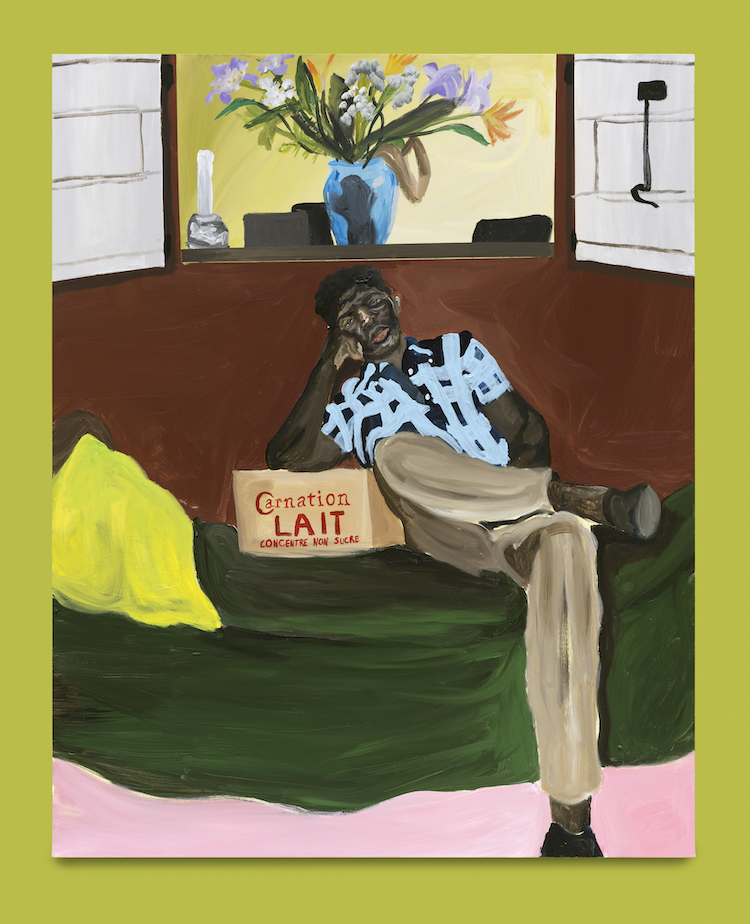

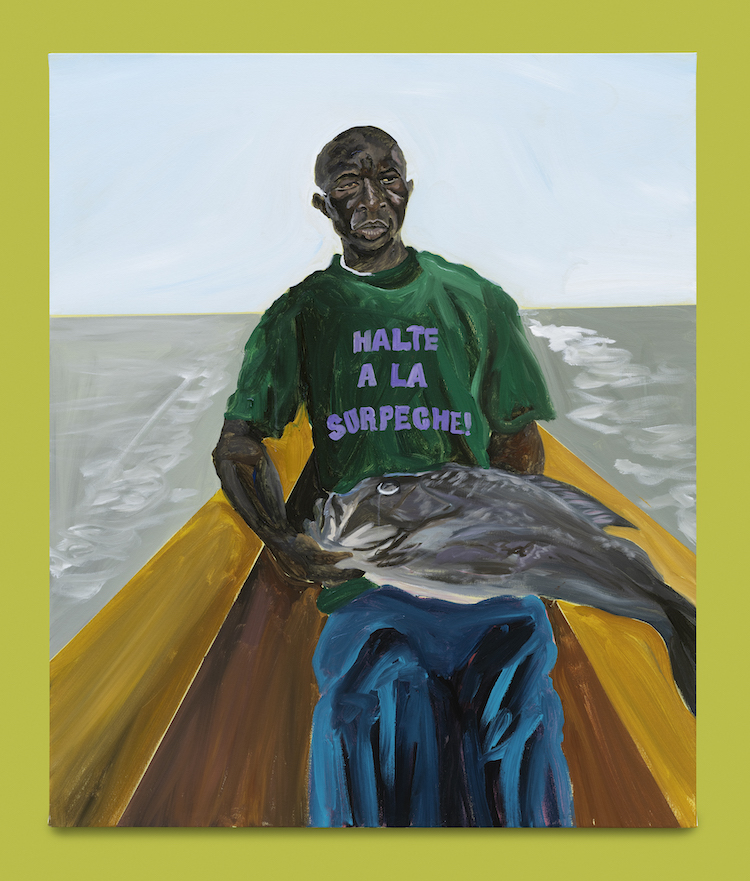

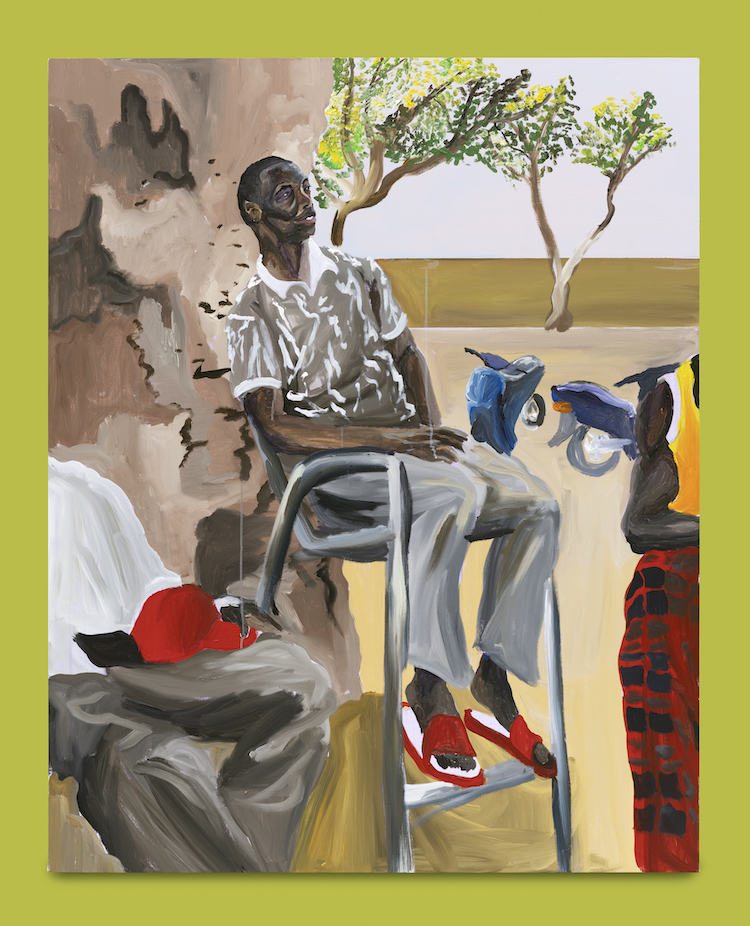

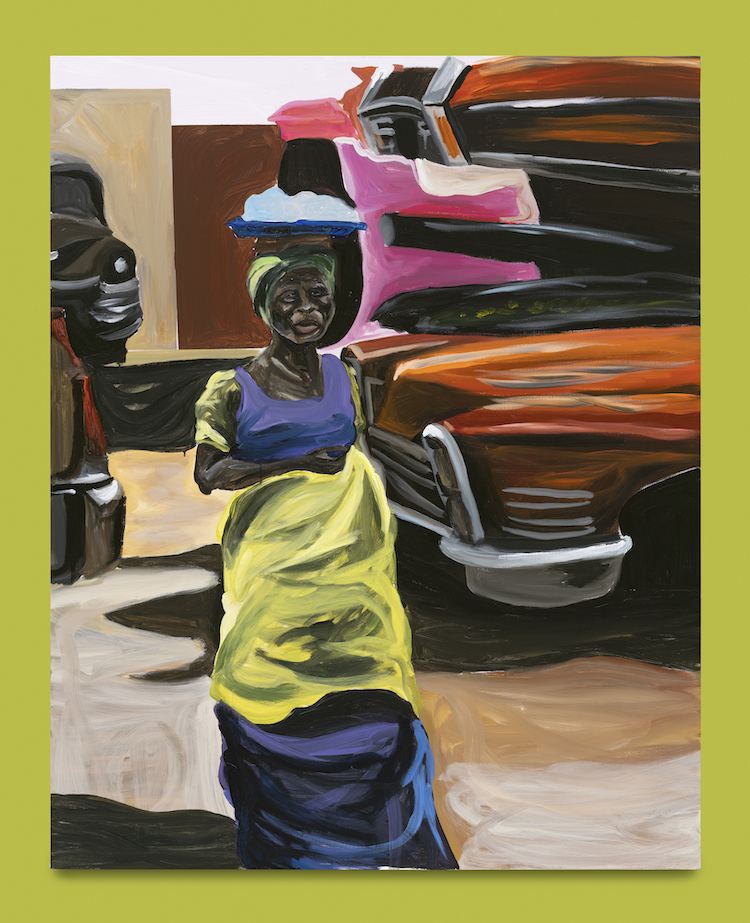

The painter fully embraces the eclecticism that has characterized his life for the past three decades, in addition to the more global eclecticism of a generation accustomed to a decontextualization and de-hierarchization of images in favor of their immediate visual impact. Brutus freely reveals the multiple sources of his compositions, which range from family photographs to extracts from African history books, as well as snapshots from fashion magazines. An avid consumer of documentaries, the artist takes many screen captures of subjects such as the man in red sandals standing on a metal chair seen on the Qatari channel Al Jazeera, and then freezes them on the canvas. Behind this seemingly innocent syncretism, to hide the relationships of domination in his choice of images would deprive the works of their symbolic power. Crossing the representations of the most affluent communities embodied in particular by the white models from advertisements with representations from the long-invisible cultures and traditions of Afro- descendant populations is both an artistic and political gesture. For if the themes that guide the young painter’s series vary, one criterion does not change: all of his subjects are Black.

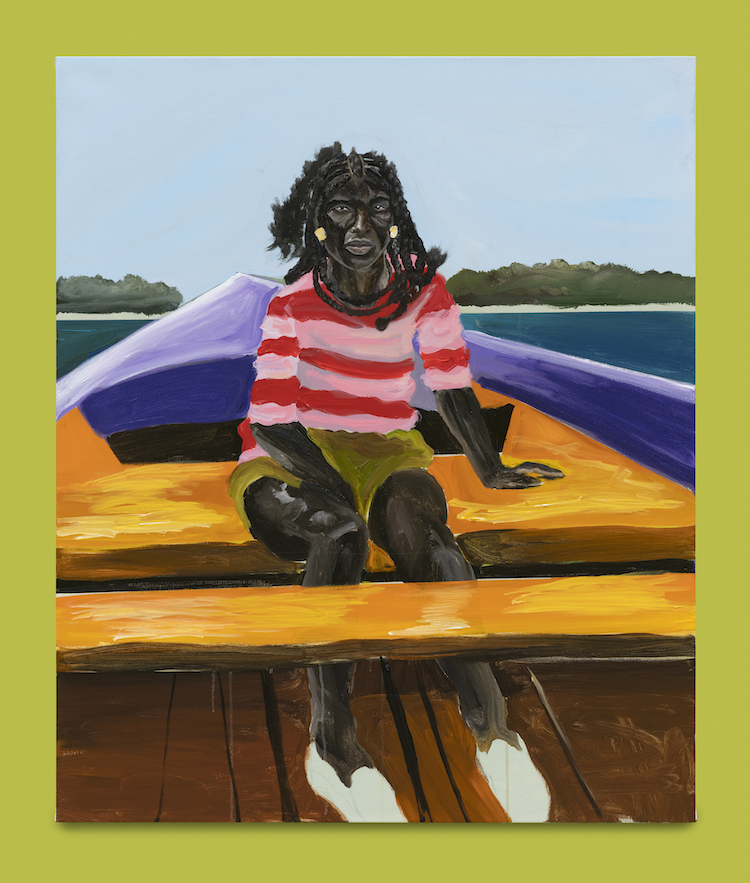

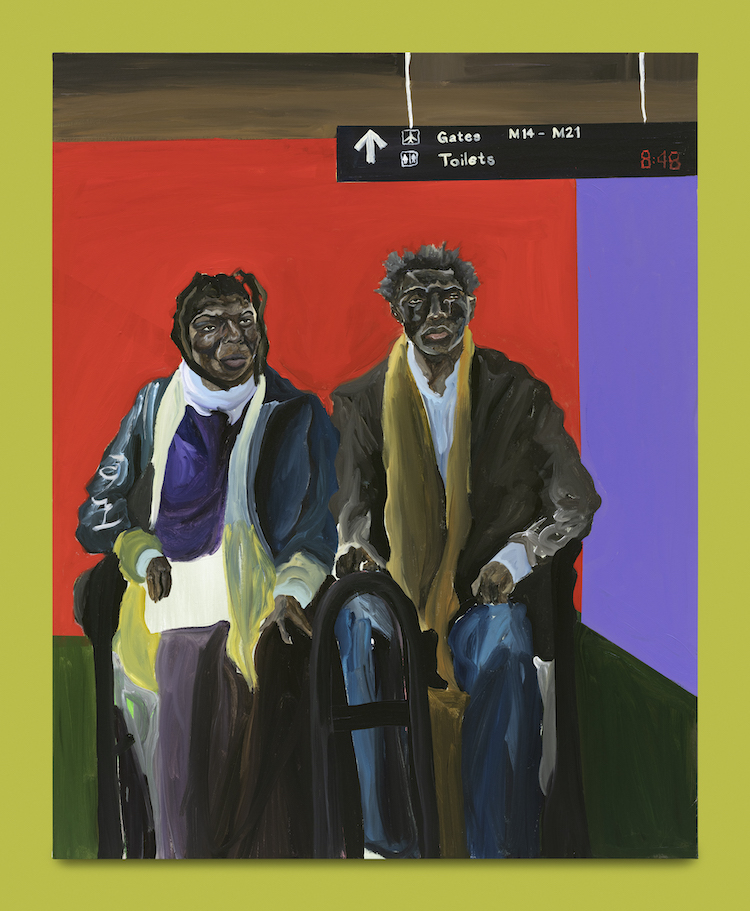

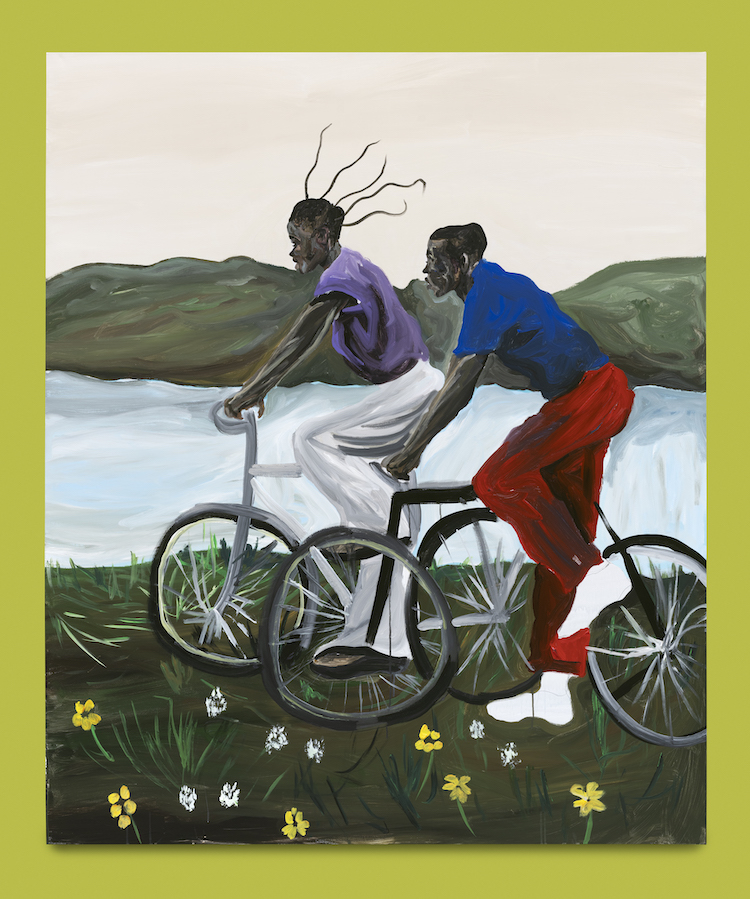

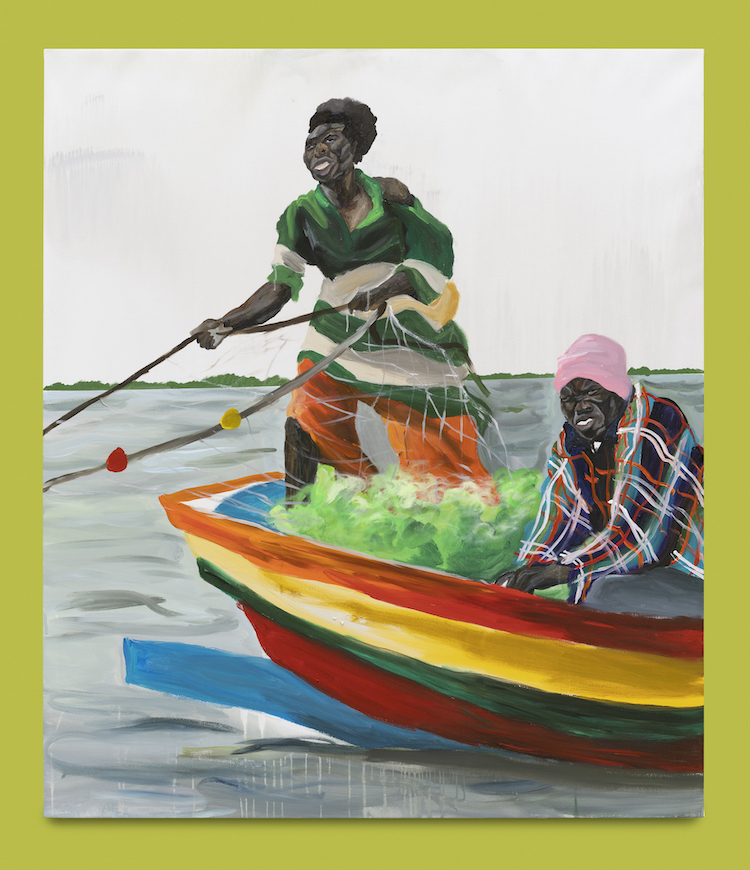

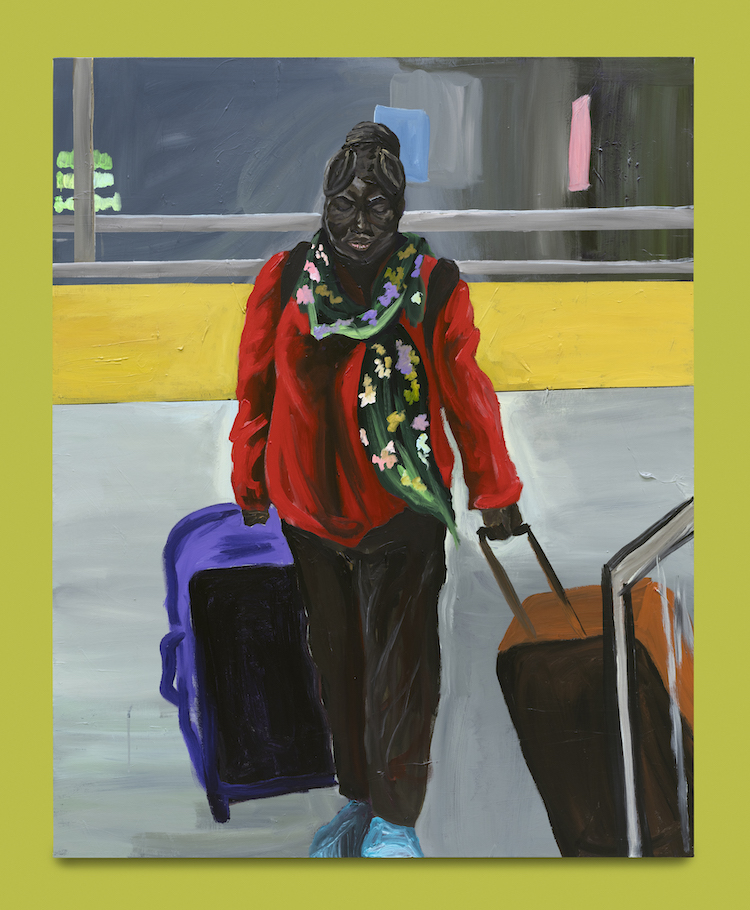

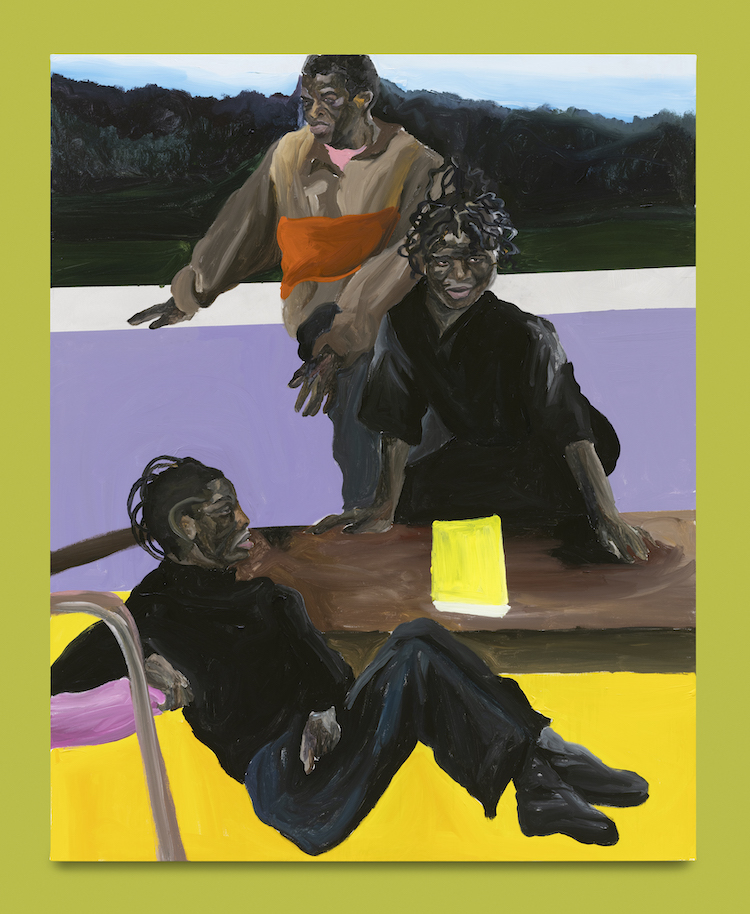

As a new figure of “Black Figuration”, Brutus could follow in the footsteps of Jacob Lawrence or Kerry James Marshall, whom he claims as influences; or Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, whose paintings all converge towards the same goal: to make the everyday life of people of color exist through painting, where before they were often absent, or often objects of fantasy and exoticism, all while avoiding the illustration of suffering. In Marcus Brutus’ work in the portrait genre which he is so fond of, his gestures are an act of renewal: straight lines are almost always absent, giving way to sinuous contours that undulate and distort the silhouettes slightly. Fixed in permanent movement, which may recall certain great symbolist or expressionist works, each element of the canvas becomes flexible, almost liquid, depicting the characters with a certain vulnerability. The artist uses scenery and clothing colors that awaken the scenes with their liveliness and bright contrast. Interested in this game of chromatic percussion, the spectator then comes to feel in the complexity and precision of the faces all the emotion transmitted by their expressions.

As his practice evolves, Marcus Brutus masters a paradoxical balance: that of exploring ever-more precise and rarely represented subjects with the goal of delivering the most universal vision of humanity possible. For his first solo exhibition in France, the thirty-year-old has immersed himself in the history of Haitians who left their country for Canada between the 1960s and 1980s, from their flight from Papa Doc’s dictatorship to their often laborious integration into the North American country. Recounted by Sean Mills in the book A Place in the Sun: Haiti, Haitians, and the Remaking of Quebec, this little-known part of 20th century history inspired the painter to create fifteen peaceful and poetic canvases, far from a historical or didactic rendition of the facts. From one work to another, the characters – often alone or in pairs – appear in diverse scenes, all linked by a common point: displacement. On horses or bicycles, on board a boat or in airport corridors, these men and women, mostly static, embody the physical and psychological state of waiting, of being in transit, between their land of birth and their new and final destination. This “poetics of exile”, as the title of the exhibition indicates, then also becomes a poetics or a questioning-through- painting the potentiality of a situation that is often forced and which still affects millions of people around the world today. As Maya Angelou also wrote, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you,” Marcus Brutus seems to respond optimistically, exploring the past for artistic purposes and countering the consequences of this suffocating silence and ignorance, and ideally forming a key to inner peace. —Matthieu Jacquet

https://stemsgallery.com/