Inès Longevial (the former Juxtapoz cover artist) paints faces and bodies traversed by silence, inhabited gracefully and modestly by vast fields of color. Creating reliefs and furrows in flesh reddened by the sun or tinged with blue in the morning, her work with light gives the female portraits the scope of a scenery and the eloquence of a story, like the contour of a dream.

So, it comes as no surprise that she invited the world of literature to take part. With Pourfendue, Inès Longevial continues her work on Nos ancêtres, a trilogy of philosophical tales by the Italian author Italo Calvino, proposing a sort of genealogy of contemporary man by way of three characters based on haunting and droll imagery.

The first part of this encounter with Calvino's literary work was embodied in a series of self-portraits and small format works permeated by the world of the forest: its shadows, its fauna, its undergrowth, and where the artist's solitude resonated with the elevation of the Le baron perché, the hero of the eponymous novel who chose to live his life up in the canopy.

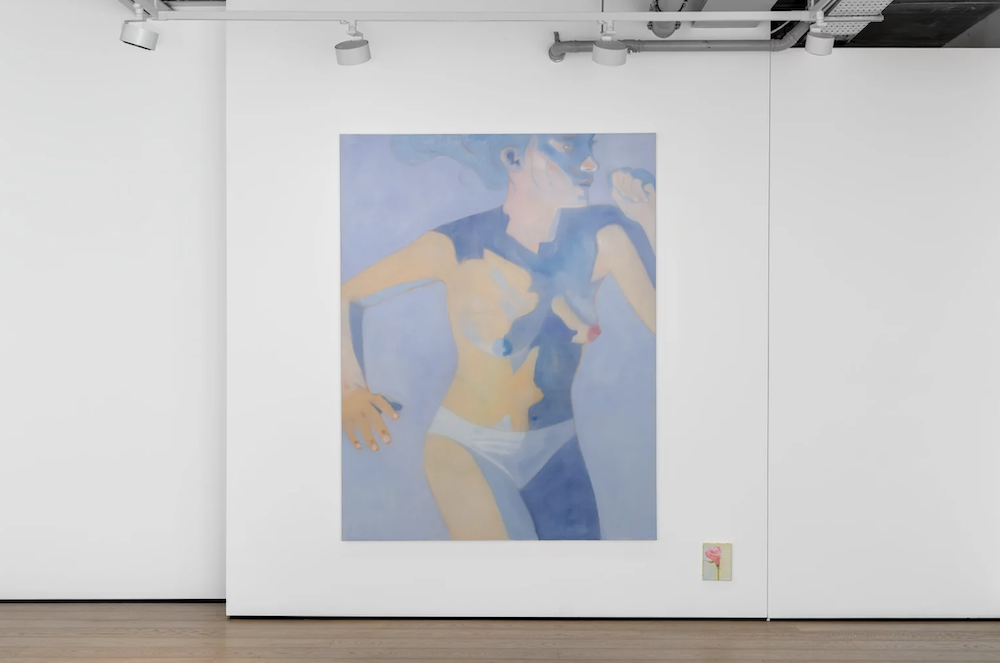

Here, Inès Longevial's work finds in Le vicomte pourfendu (the first volume in his "heraldic trilogy") a particular echo of aesthetic biases that have been running through her work for several years: a true point of convergence, the motif of the half, the double, and by extension the idea of duality testifying the artist's relationship to her work. The parabolic tale is defined by the notion of a split, that of the Genoese Médardo de Terralba cut in two by a shell during the war, and the subsequent encounter between his two halves which survived independently, one inhabited by evil and the other by good. Yet working in pairs, with "sympathy" and the choice of diptychs and symmetry, the tight framing that favors the part rather than the whole, and the contrasting of palettes where warm and cold colors find a new definition… All of these contribute to a form of resolution in Inès Longevial's work which reflects both the painter's obsession with slicing and dicing her subject in order to understand it better, as well as her desire for reconciliation. “‘So, if I could cut all whole things in half,’ says my uncle, lying flat on his stomach, caressing these contracted octopus halves, ‘then everyone could come out of their obtuse, ignorant wholeness. I was whole and everything was natural and confused to me, stupid as air; I thought I saw everything and it was only the bark.’"*

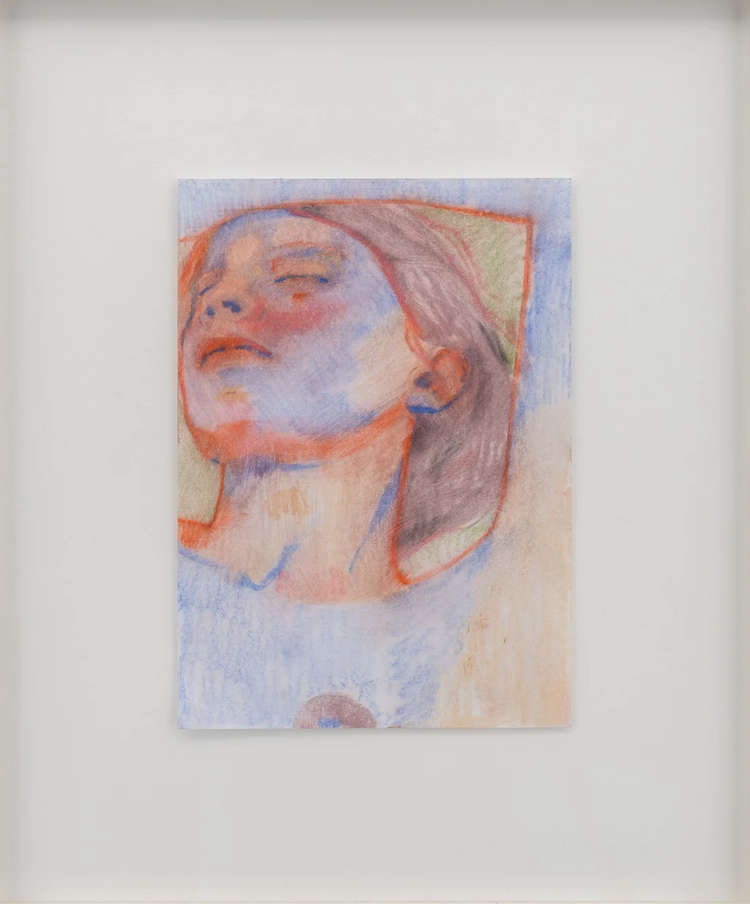

Just as the artist dissects his subject, observing it from within, and beyond the visual examination seeks to understand its truth, the viscount never ceases to chop in two everything he finds in his path in a process that is both destructive and hungry for meaning. Inès Longevial has taken this approach a step further, by expressing her vision into small formats with roses or pears cut down the middle which punctuate the exhibition. A move that is both graphic and poetic, shrouded in the softness of fading colors and her characteristic tonal delicacy, and enhanced by the bright hues around the edges which recall a child’s imagination and fairy tale symbolism. Inès Longevial's work is defined above all by her sensitive relationship to color and light, materials that resonate with the world's infinite nuances and the emotions they arouse. Every hour, every season, every memory offers a palette that the artist confronts with neighboring or opposing hues, as a composer would play between scales and their relatives within the same score.

Thus, beyond the twin nature of the faces, two portraits respond to each other through the complementarity and porosity of yellows and pinks, matching each other like a reverse image of the other. Three large canvases also feature cameos of blue, sometimes leaning towards mauve, sometimes towards grey or green — the preferred colors of shadow painting — where Inès Longevial has always demonstrated great freedom. Moreover, in their frankness and the assertive slicing and autonomy of their drawing, these shadows become detailed, cutting through their subject, sometimes even at its center. Here again, the artist plays on the interplay of opposites: a form of tenderness, of harmonic empathy with the painted model, and exacerbated light relationships that undress as much as they clothe. These works are also an opportunity for the artist to experiment further with movement and bodily intention, i.e. beyond the pulsating life of the complexion. With a gestural, spontaneous touch, the works on paper also highlight the links, dynamics, and forces underlying the chromatic rendering of the canvases. The addition or subtraction of colors is deliberately visible, and the essential play of shadows is often summed up in a stroke of pastel, a bold line in a shade that, once again, contrasts with the skin coloration. —Eva Pion, writer