There are just so many highly-anticipated exhibitions kicking off the fall season, from Amy Sherald to Robin F Williams, Derrick Adams to Henry Chalfant. But one that we have had our eyes on for month's is the debut Gagosian Gallery exhibition of NYC-based Nathaniel Mary Quinn. In what feels to be one of the most important artists of his generation, and with a career ascension that is equally matched but his stunning works, Quinn's Hollow and Cut caps off an impressive two-year run for the artist, one that has seen shows at Salon 94, Almine Rech, M+B and now this major showing at Gagosian in Beverly Hills.

"Confronting insecurities and fears, embracing shortcomings, and contending with the burden of one’s own identity and truth are of paramount importance for becoming more concretely formed," Quinn says of his new work and exhibition. "My current studio practice maintains this endeavor: cutting through, digging out, excavating, laying bare wounds—past and present, temporary and permanent—on the surfaces of paper and canvas."

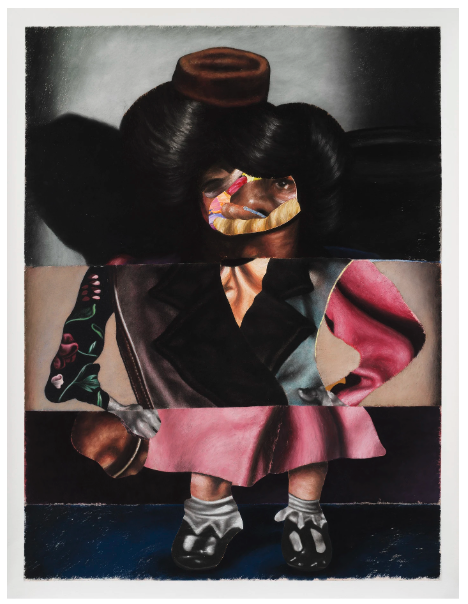

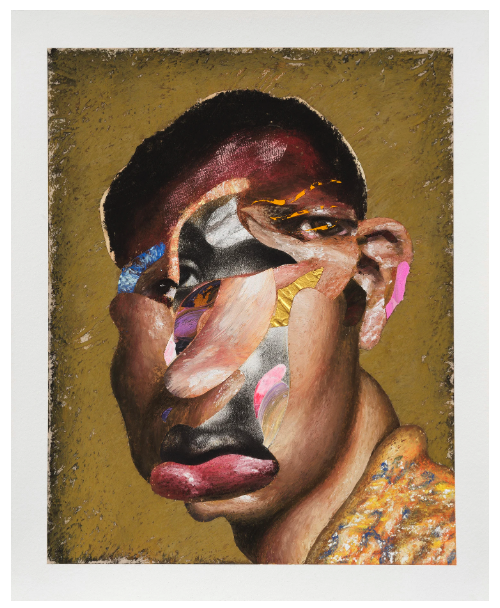

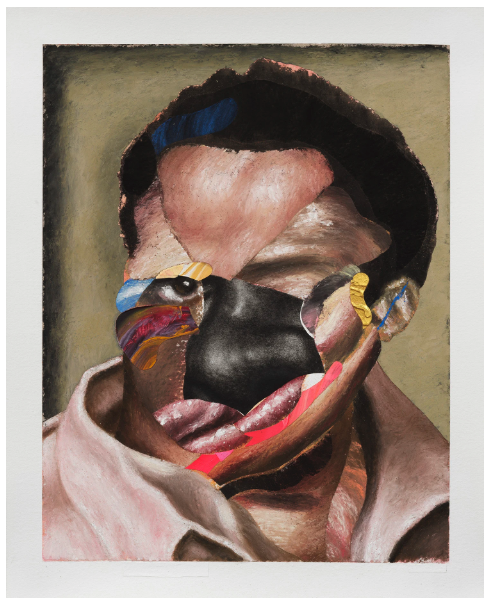

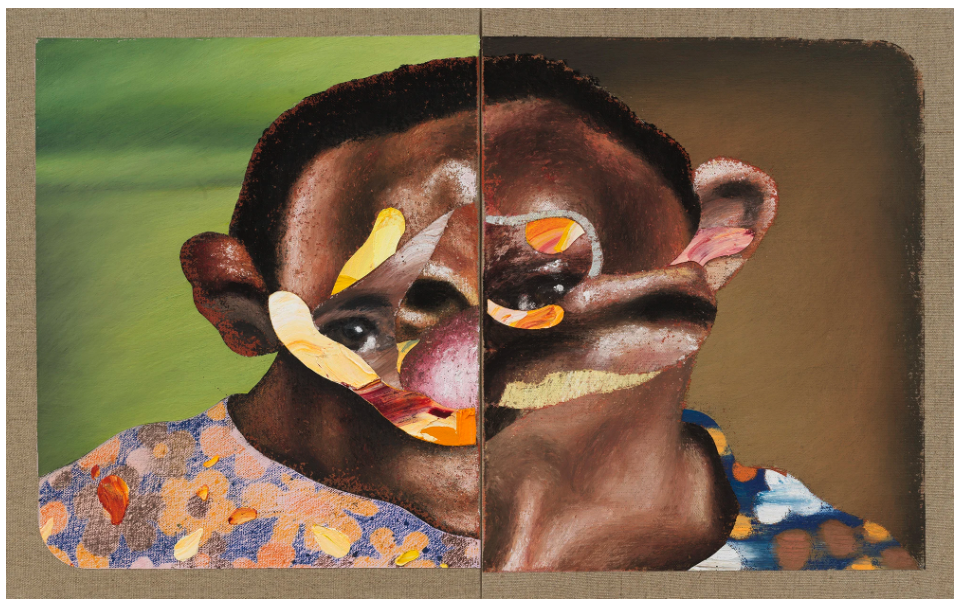

As the gallery notes, who coincided Quinn's exhibition with a cover story in the Gagosian Quarterly: On view will be a number of Quinn’s “enhanced performance” drawings: 12-by-9-inch charcoal-on-paper works created simultaneously with both hands and “enhanced” with colorful swipes and swaths of gouache and soft pastels. For the ambidextrous Quinn, the technique behind these works is a full-body performance in itself that expands upon his already spontaneous act of rendering visions—yet the end result is surprisingly representational. Depicting complete faces rather than patchwork body parts, these haunting portraits slip in and out of focus through a murky haze of black charcoal. Hollow and Cut will also feature new paintings, including Quinn’s second ever horizontal diptych, Jekyll and Hyde (2019), in which he dramatizes the process of visual fragmentation and reassembly by painting each half of the subject’s head separately before joining the two canvases. The strips of bare linen around the edges of each painting also emphasize this three-dimensionality and physicality. Using further perspectival sleight of hand, Quinn then paints the newly constricted edges of the work in a darker, shadowlike gradient, as if framing his portraits through an inset window. Confined within the world of the canvas, his swirling, distorted faces gaze out at us with raw emotion, baring their psychic vulnerabilities.

Above: Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Sinking, 2019, oil paint, paint stick, oil pastel, and gouache on linen canvas over wood panel, 36 × 36 inches (91.4 × 91.4 cm)