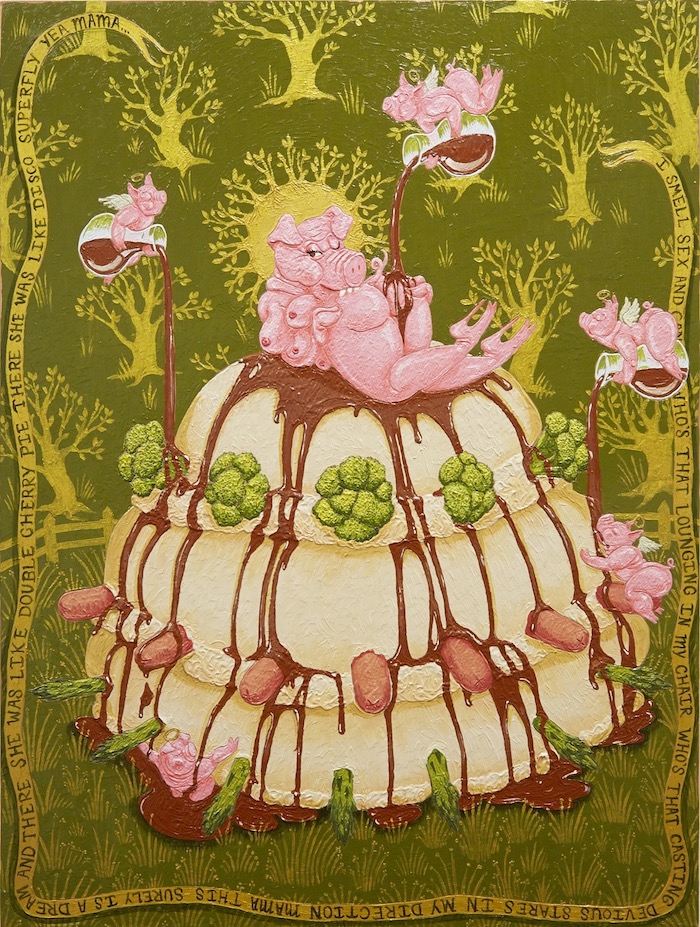

One year since her debut solo show with Monya Rowe Gallery in NYC, Anastasiya Tarasenko is wrapping up another year with an exciting and thought-provoking exhibition. Still focused on the themes surrounding consumerism, greed, politics, sex, and feminism while utilizing an ingenious technique of using materials, the imagery is pushed further into a fantastical sphere in order to create stronger and universally applicable metaphors.

Replacing the human protagonists with pigs, chickens, and other farm animals, Tarasenko is certainly making the work easier to swallow while throwing a more powerful punch. Composed within formats heavily influenced by Medieval art, Illuminated manuscripts, and religious or similar dogmatic iconography, the bizarre narratives are harmonizing the almost slapstick, comic-like humor with the sobering familiarity and actuality. And this aspect is certainly accentuated with the unique painting technique that the Ukrainian-born artists developed over the years. "I believe in art as a physical object just as much as a visual one. Copper has a certain gravity to it that is difficult to translate in photo form but lends itself to a very luscious way of painting. I want people to want to touch my paintings, run their fingers over them, experience more than just with their eyes," the artist told Juxtapoz about the background of the most notable technical peculiarity about her work. Unhappy with the traditional surfaces like canvas and wood as well as influenced by the folk objects from her childhood, she started painting on copper, purposely going beyond the visual sphere. But besides the tactile effect, such an approach has a more profound, emotive connection for the artist. "As a Ukrainian, I grew up surrounded by folk objects my parents managed to take with us when we moved to the states. Things like wood lacquered dishes and spoons painted in rich gold, red and black designs as well as beautiful miniature paintings depicting famous folk tales. This current show was definitely informed by my love for Slavic folk arts as well as European medieval copper and gold reliquary boxes, plaques, and sculptures," she told us about the influences that informed both the technique as well as compositions and the ways in which narrative is laid out.

Although citing folk art and Baroque as the biggest influences for this body of work, we couldn't help but ask about her relationship with Animal Farm. "Yes, I would say that there is a strong relationship between Orwell's apt use of farm animals and my own. The pigs killing other, non-compliant pigs and animals, the deviousness of power hierarchies, etc. Somehow, people are able to better digest stories of the human condition when they are presented in metaphor, like animals," Tarasenko told us about the way her work relates to the famed satirical allegorical novella. But while Orwell was interested in delivering a critique against Stalin and his totalitarian autocracy, the NYC-based artist is providing sharp social and moral observations as seen through a female perspective. "Femme bodies, in particular, are under constant scrutiny and described in language also used to describe food. A woman's body, historically, is her biggest form of currency because we have been isolated from true financial independence, using the body as a means of securing a mate who can provide. So being in this body feels very much like being in a piece of meat that I am responsible for maintaining desirable," the artist explains the relationship between livestock and humanity, or more precisely, femininity. Through such an approach, she is revealing the hidden hypocrisies existing in everyday expectations and conventions and offering a "shockingly" different proposal. "This body is the way I experience being human. A traditional human is a man in art, literature, etc. An everyman is a man. I want to challenge the idea that when we see women's bodies in art they can only represent women's problems and burdens. A woman can be everyman too," Tarasenko rejecs the current state of things in an effort to rewrite history and the existing social hierarchies. —Sasha Bogojev