Harper’s is pleased to announce Stockholm Syndrome, Enoc Perez’s fourth solo presentation with the gallery. The exhibition features new paintings by the influential Puerto Rico-born, New York-based artist. Stockholm Syndrome is on view through November 11, 2023.

As the son of an art critic, Perez began to study painting at the age of eight. The artist was immersed in art cultures throughout his childhood in San Juan: he regularly frequented museums and became well acquainted with the pedagogies of art history throughout his youth. Perez moved to New York City in the 1980s to commence his formal training in painting at Pratt Institute. During this time, he developed a fascination with the architecture of New York and the political motivations that imposing structures represent across the globe.

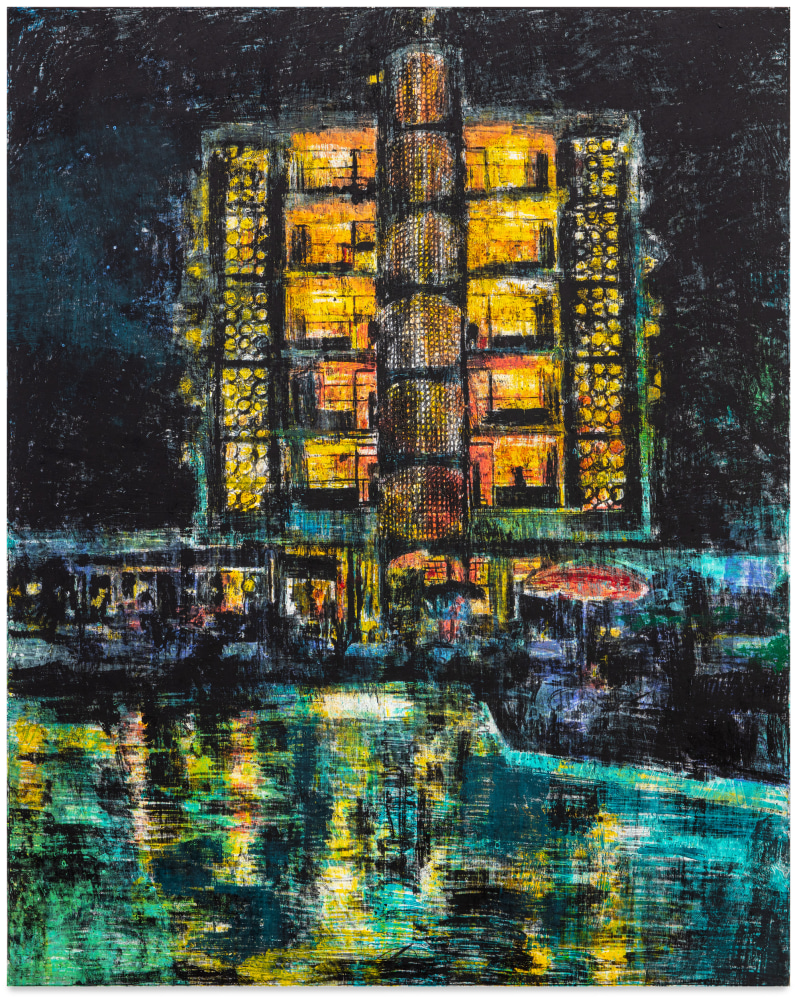

He began to paint significant modernist towers, paying keen attention to the ideological symbols these man-made monuments diffuse. Perez frequently illustrated grand hotels, US embassies, and airports with his distinctive approach to mark-making—a de facto printmaking practice that involves imprinting oil paint onto canvas using drawings on sheets of tracing paper. These works reached critical acclaim in the late 1990s and have since been incorporated into the collections of the Whitney Museum, British Museum, and Metropolitan Museum of Art, among many others.

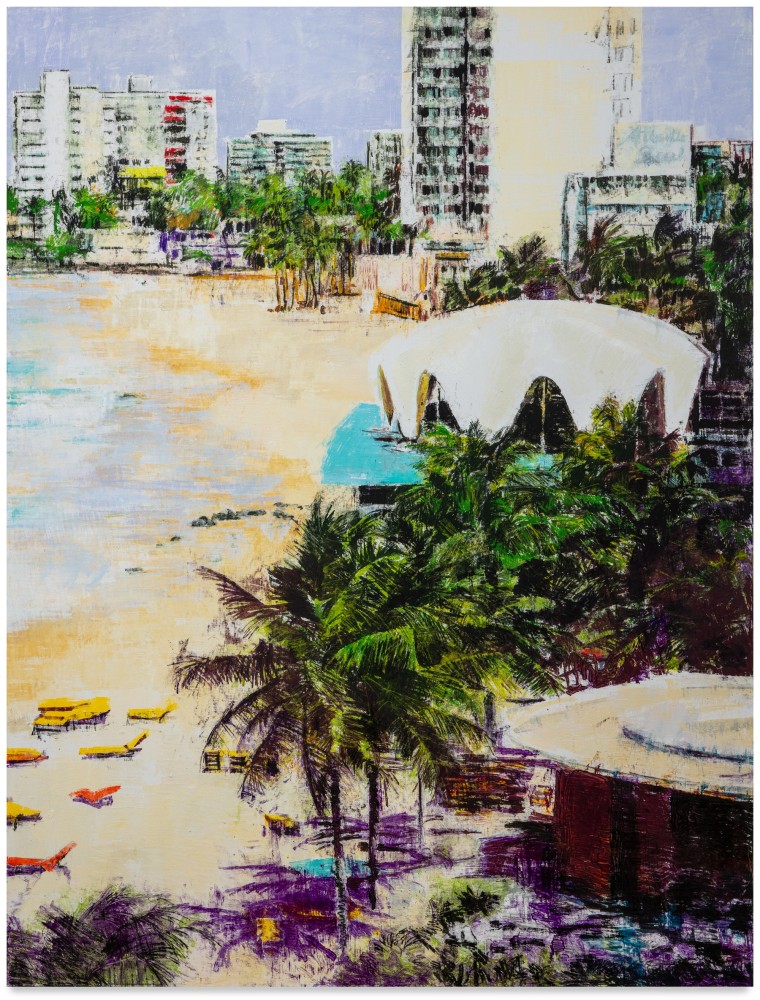

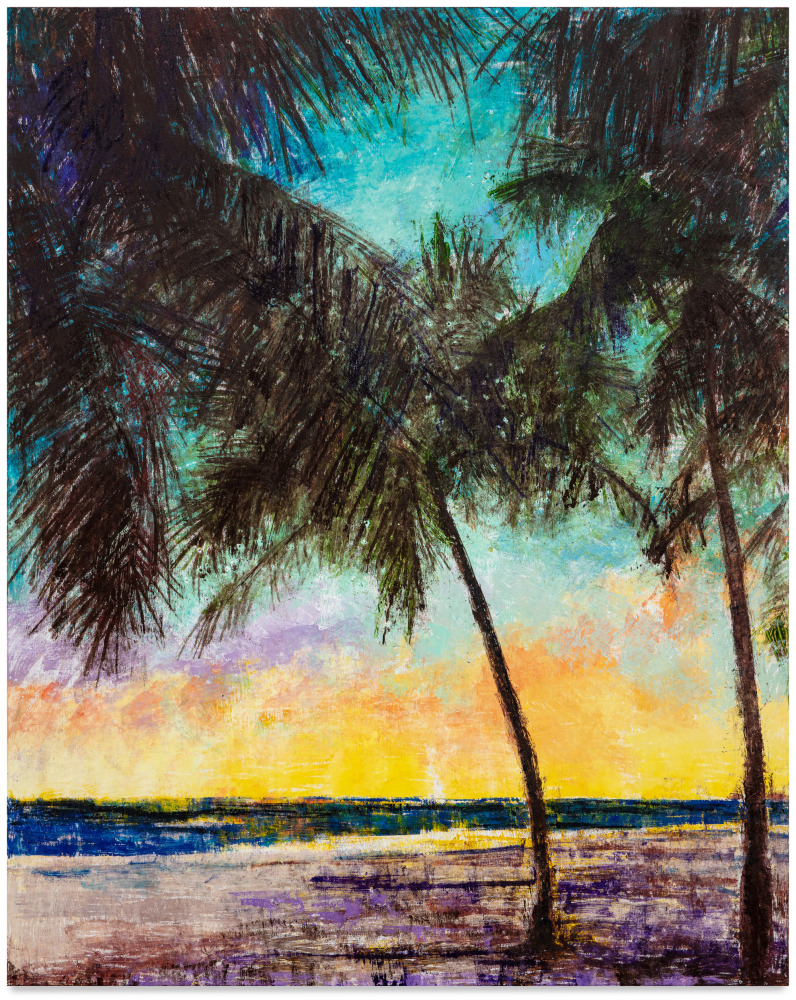

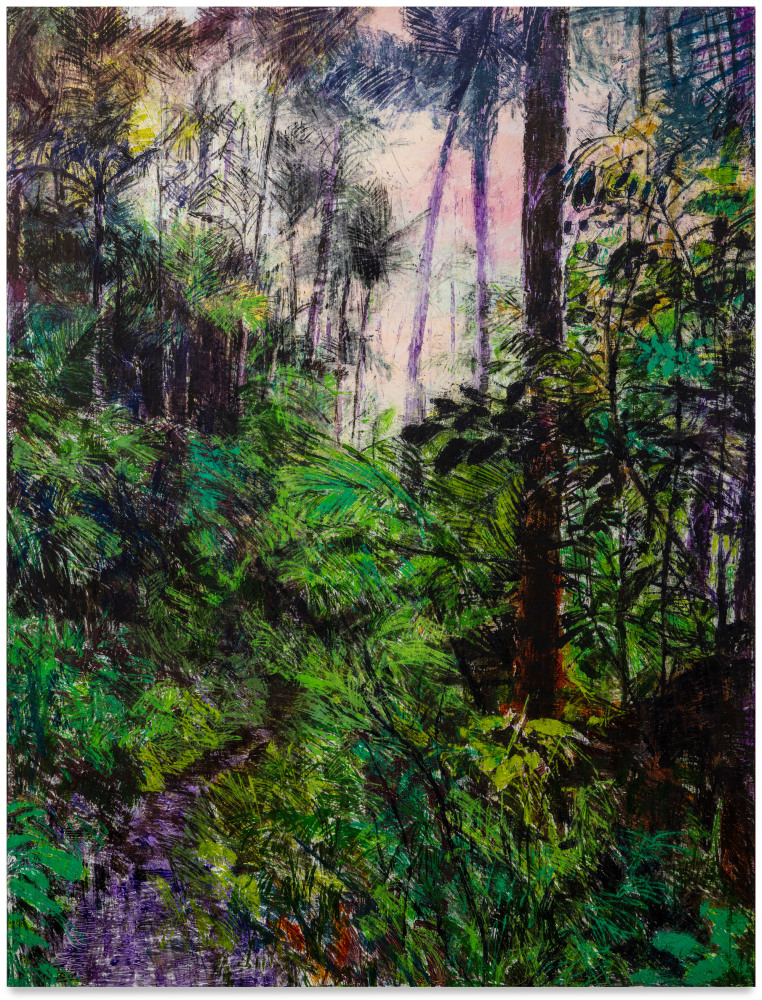

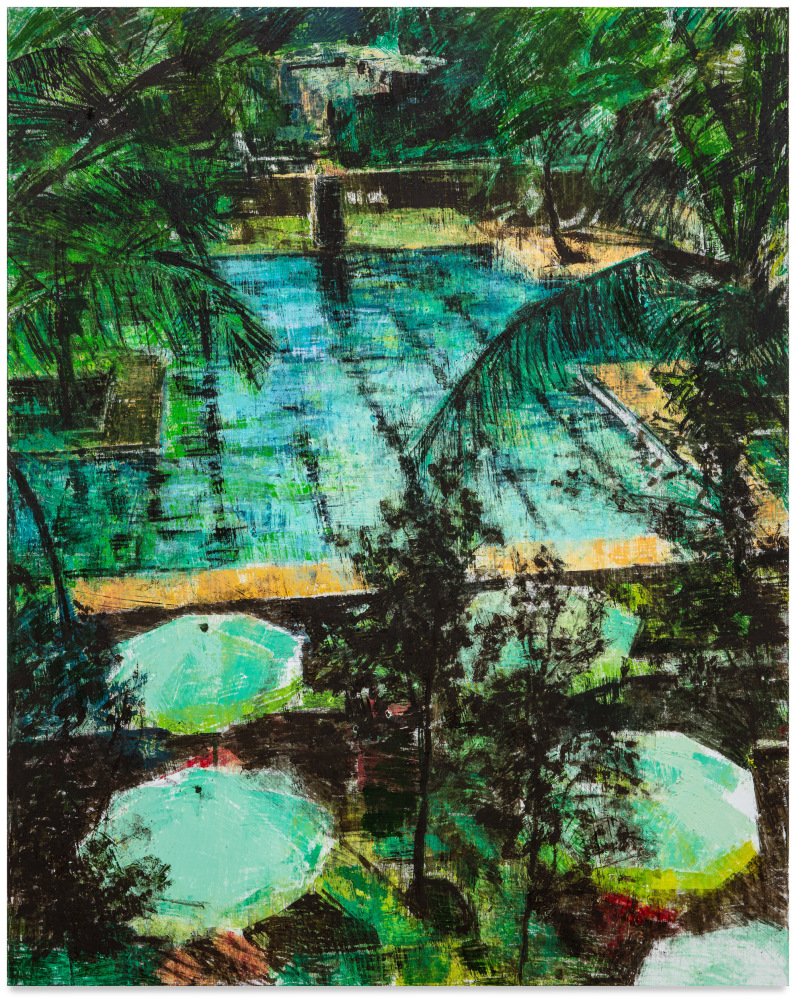

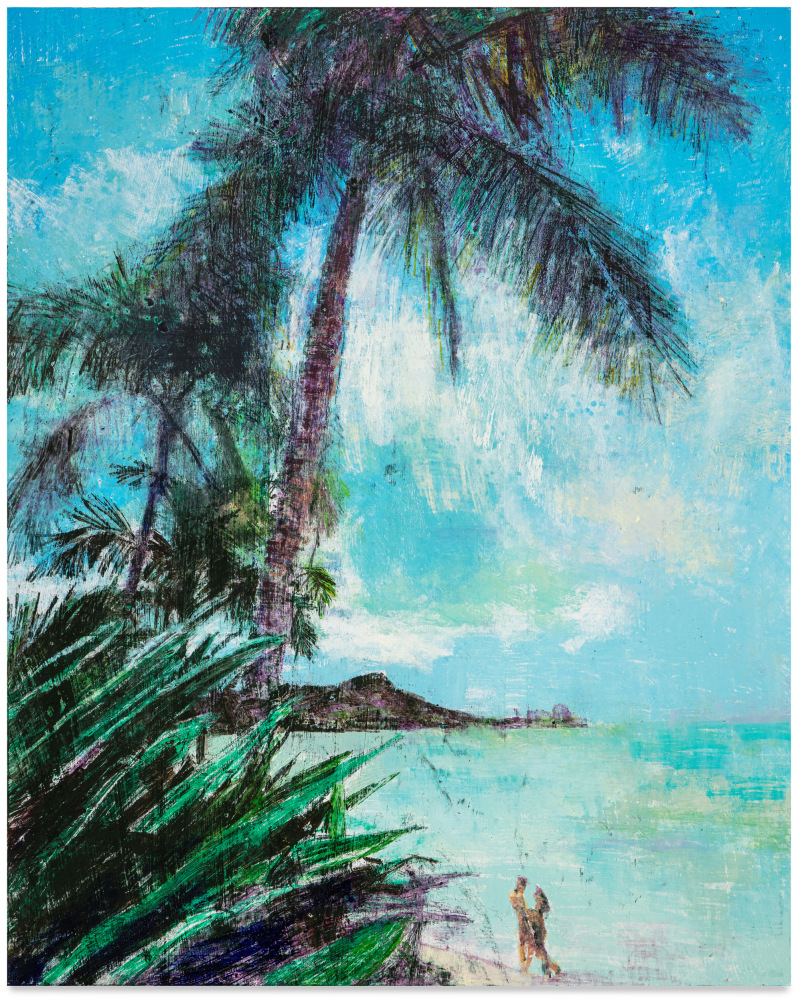

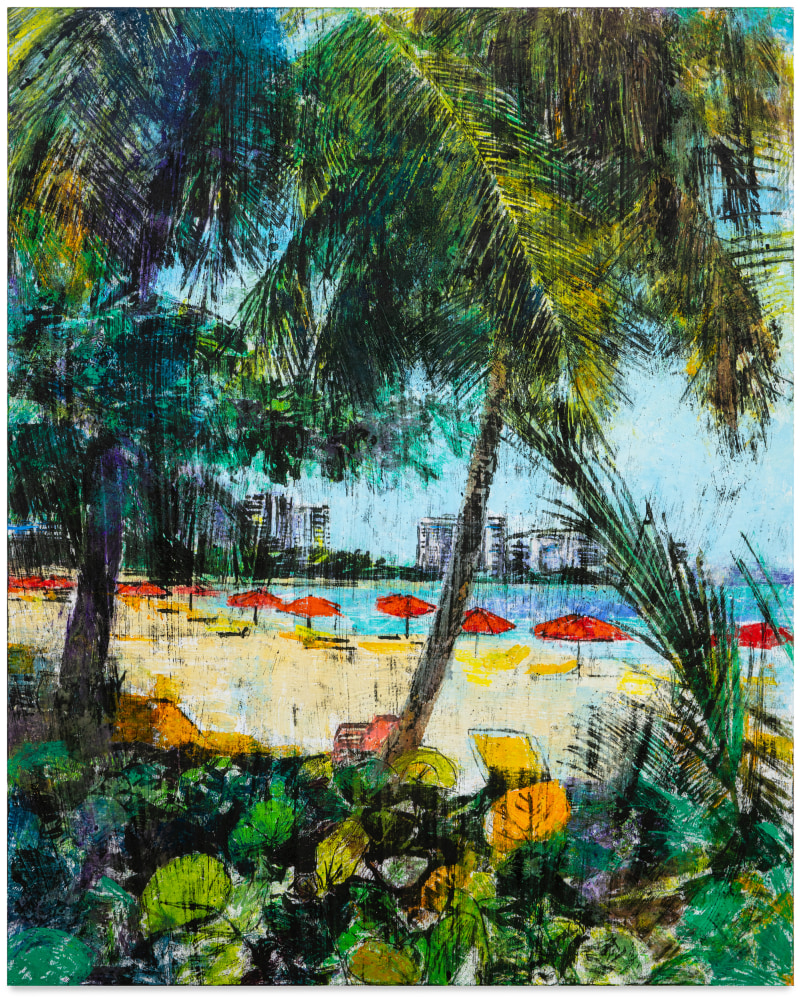

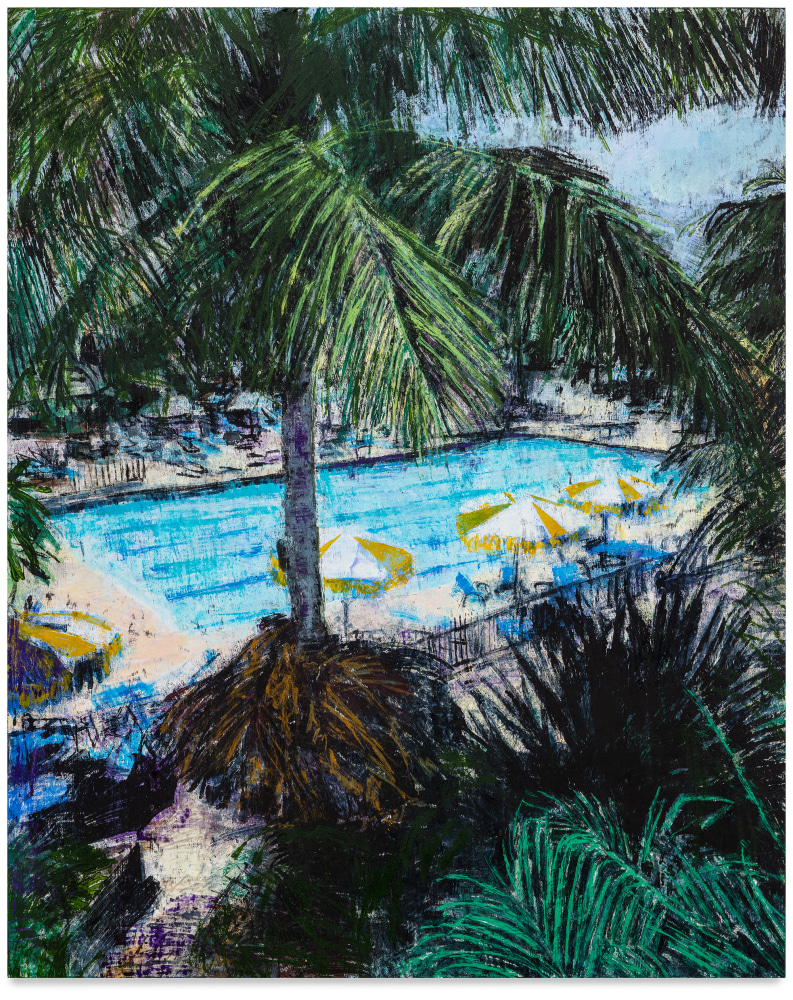

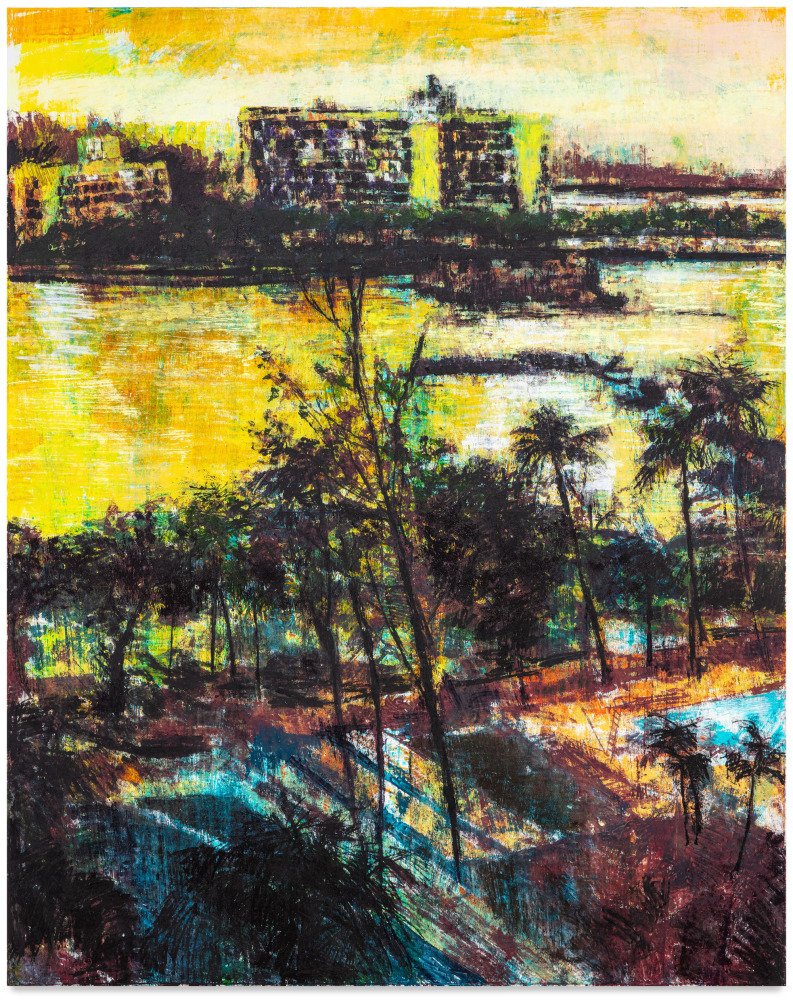

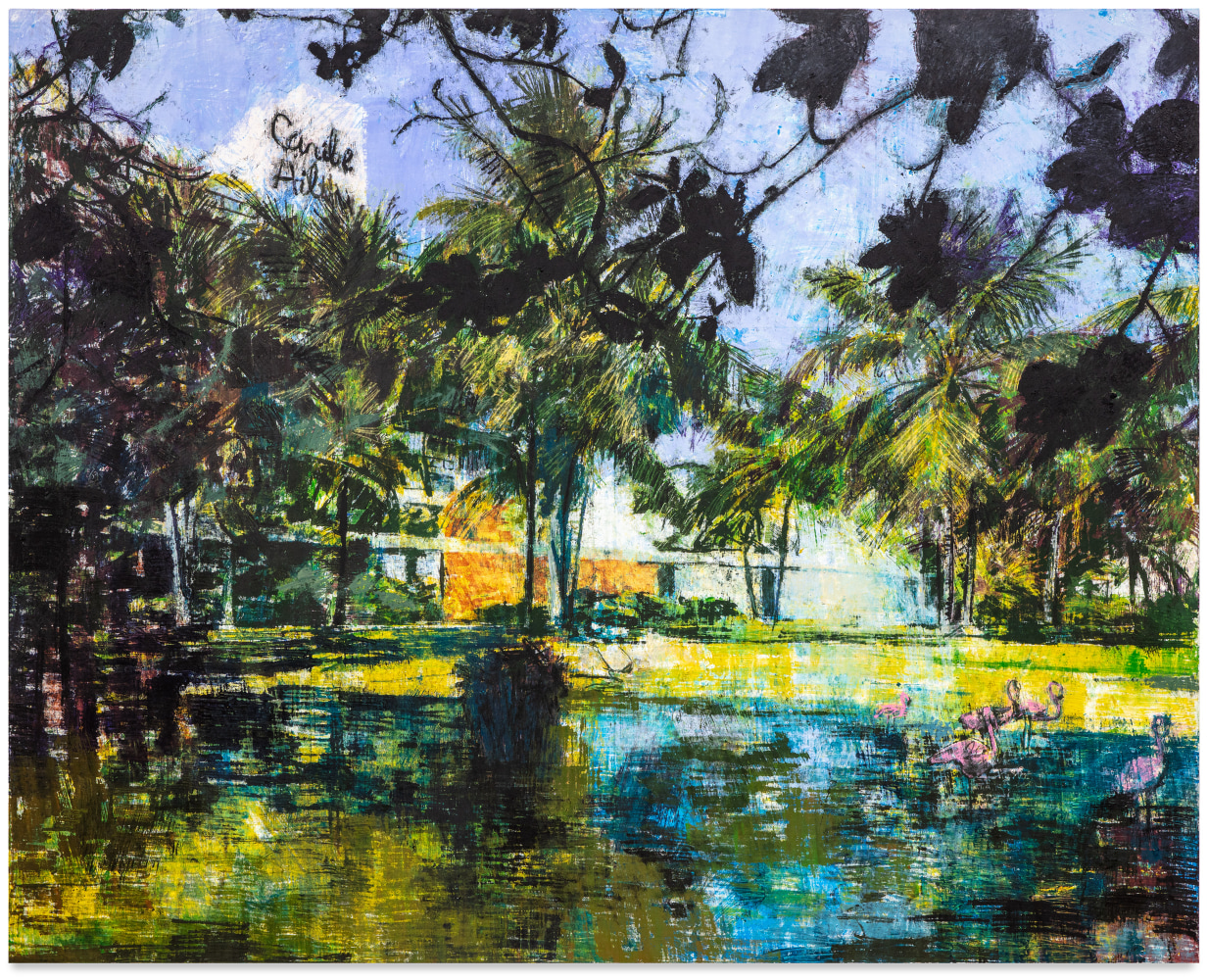

In Stockholm Syndrome, Perez continues to enmesh traditions of printmaking and oil painting to examine the intersections of architecture, geography, and colonialism. In this recent body of work, he grounds his study in the aesthetics of tropical paradise in the Caribbean. When visually rendered, paradise is a site of infinite indulgence: sumptuous landscapes are replete with pristine beaches, turquoise waters, and bountiful food and drink. These are the vistas of leisure that decorate the covers of resort brochures and travel catalogs; they document sought-after vacation havens across geographies ranging from the Caribbean to Southeast Asia. Perez derives inspiration from this touristic ephemera. For the artist, the imagery constitutes the insidiousness of consumerism in Puerto Rico and across the Caribbean at large, but the material also presents an important vantage from which to consider for whom the optics of tropical paradise serve and for whom they exclude.

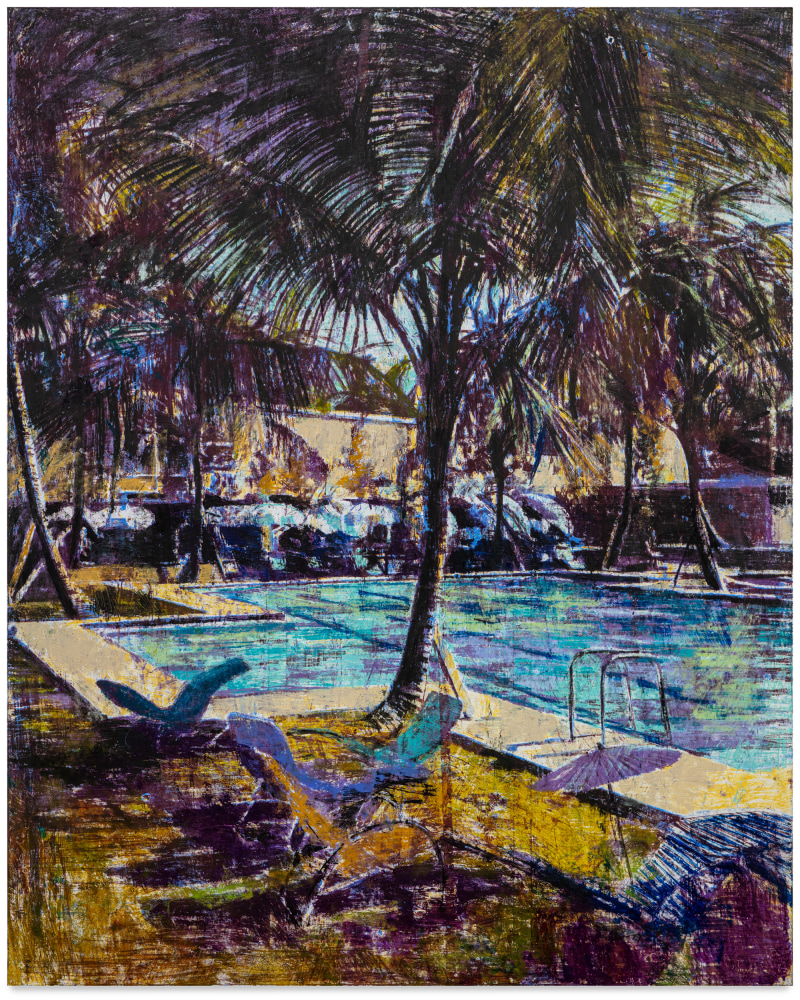

The works that comprise Stockholm Syndrome thus render what Perez refers to as the “dream of abundance”—the fantasy of pleasure as told to visitors and natives alike. The protagonists of these new paintings are those moonlit hotels, luxury imports, and crystal pools that advance the infectious dream of respite. An avid collector of Caribbean travel paraphernalia, Perez gathers source images for these paintings from a range of promotional material he’s amassed over time.

His collection of postcards and resort brochures inform works like Pool at Dorado Beach Hotel, Puerto Rico, which sets the timeless beauty of the Caribbean landscape against the backdrop of a vacation haven. Here, leafy palm trees, detailed with a spectrum of vibrant greens, purples, and yellows, shade a cerulean pool that reflects washes of lilac and milky green. Perez’s extraordinary convergence of printmaking and painting is particularly resonant here and throughout: the artist is able to strike gritty shadows of lavender and magenta that obscure the otherwise unspoiled landscape, pushing the work into the realm of abstraction while recalling the fervent spirit of pop art and reproducible media. This experimental paint application invokes paramount legacies of printmaking in Puerto Rico. The practice has had an indelible impact on the island’s cultural production: notable artists like Rafael Tufiño popularized the medium in the mid-twentieth century during the territory’s graphic arts movement and today, this form of expression continues to play an important role in the island’s representation in media and popular culture.

Conceptually, Perez’s implementation of printmaking techniques excavates the artificiality of the idea of tropical paradise itself, an ideological tension that remains at the fore of the exhibition. His process-oriented practice, which requires attentive manipulation of the visual plane, reflects the calculated design work involved in the manufacturing of the illusion of paradise. To this end, Perez invites viewers to decipher the narratives that are difficult to discern—those realities overshadowed by the sublime optimism of a consumerist gaze—by unleashing poetic layers of obfuscation.

These covert suggestions of critique feel present in works like Master of Ceremonies and When the Going Gets Tough, It Is Nice To Know You Are Loved. Both works are inspired by the artist’s collection of vintage Bacardi rum advertisements from the 1960s. Tall and empty bottles of Bacardi, adorned with temptatious gold labels stand proudly over ice-cold glasses, bottles of club soda, and fruity cocktails. They tower like looming monuments, iconographically referencing hedonist indulgence and pleasure, but also, the deleterious weapon that alcohol can become.

Still, when observed together, the prismatic works that comprise Stockholm Syndrome are hopeful in tone. They ask viewers to consider the awe-inspiring potential that lies within utopic imagination, despite the perils of neoliberal marketing. Through painting, Perez demands we envision what paradise might feel like and how such speculation could incite more liberated realities. Stockholm Syndrome, in this sense, is a proud reclamation of the tropical imaginary: the artist declares that these contested landscapes should not be solely relegated to the tourist’s gaze but instead, celebrated by those for whom paradise is home—not a place of temporary escape. —Daniella Brito