Brooklyn-based painter Asif Hoque just opened a stellar solo show, The American Loverboy, at the Notting Hill location of Taymour Grahne Projects in London. In conjunction with the show, Dr Cleo Roberts-Komireddi wrote as essay, "A Loverboy that cares," that we wanted to share below.

The vaults of today’s Britain’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office are an odd place for a painting that depicts India genuflecting before its white colonial masters. The elaborate 18th century oil painting exalts the East India Company. In front of one of their signature ships that plied the Empire’s oceans, Britannia is dressed in swathes of Dhaka muslin, the most valuable fabric at the time. India kneels at Britannia’s feet and proffers a tray over-spilling with gems and strings of pearls. China is represented in the foreground by a figure who cannot give the Ming vase away fast enough. The year of its painting was the apex of Britain’s exports from Asia. That this crushing image, ‘The East Offering its Riches to Britannia’, remains the property of the FCDO—and indeed has hung on its gilded walls greeting the great and good as they ascend to meeting rooms presumably to discuss the severe cuts to foreign aid budgets—bespeaks a disturbing amnesia.

When the artist Spiridione Roma whipped up this image of deference and despotism he had never travelled out of Italy. His ten foot wide, over eight foot high painting was steered by the Directors of the East India Company. It was in their nature to aggrandise their ‘corporate confidence’. And such was the self- serving value of the artwork that it was grafted onto their boardroom ceiling. ‘Such depictions of authority’, as Swati Chattopadhyay has asserted, ‘was repeated in the next hundred years until the differential positionality of Britain and the East became naturalized to the eye’.

Hoque steals this swollen oval for his epic work, ‘Protect her at All Cost’, 2021, and fills it with his fiction: bombastic uninhibited forms surfing his puffed up skies. He does away with Roma’s oppressive exotica and places a brown woman at the centre. Flanked by Pegasus and a lion, she is lifted up, standing firm and glistening. A billow of gold silk cascades across her body and flies up into the sky. There is a similar trail of fabric in Roma’s original. The excess of Britannia’s starchy white dress blows away from her body and provides shelter for a cowering group of putti. It is bewildering that these podgy infants with fresh-faced buttocks and stubby limbs are representative of the East India Company officials. They cower and cling to each other.

In Hoque’s pastiche, no one shrinks or recoils. A cluster of cherubim flit around, all bright and breezy. Eros is there, poised to fire up love. In a reversal of Roma’s depiction, he assumes Mercury’s position. At his feet lies the god’s caduceus, a symbol so associated with mercantile endeavour that it was integrated into the East India Company’s visual culture. Most prominently, it festooned the entrance of their Blackwall Goods Yard. But here, in Hoque’s image, the staff is rocked out of Mercury’s hand leaving its ideals of commerce floored.

Hoque’s caboodle of characters emit superhero bravado. They burst forth from the luxurious indigo sky and are flecked with gold. It is perhaps no coincidence that Hoque chooses this bluest of blue for his cast: the majestic pigment was viciously extracted from Bengal and its Delta by the Company. Through a system of intense manufacture, the colour was commercialized and exported. As an enquiry in 1860 into its production stated, "not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood". In Hoque’s lavish application of this colour is reinforced the idea that a generous offering from East to West, promoted by the brush of Spiridione Roma, was a profound fallacy.

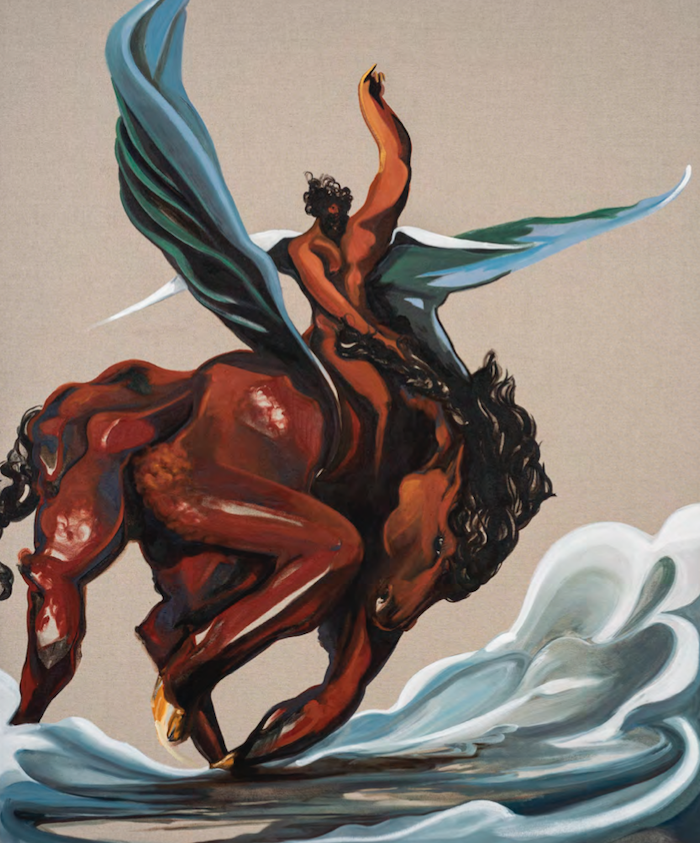

Hoque’s untangling of this East India Company commission— symptomatic of art history’s vision of inferior brown figures— conjures a noble serenity. Hoque speaks of his desire to ‘paint brown figures in a more loving and caring way’. And in line with his tender approach he has created ‘The American Loverboy’. Loverboy is Hoque’s heroic character; a cupid with the musculature of a Classical sculpture crossed with the fearlessness of a Malboro-man cum Richard Prince strain of cowboy. Except he’s brown and has thick corkscrew curled hair. He charges across Hoque’s canvases upon the back of Pegasus and together they skim through clouds, the horse’s thunderous thighs and buttocks almost trembling, as they race to rescue their damsel in distress.

Cowboy myths like these belong to the Western world and, most emphatically, America. In popular culture they have never been brown before, let alone representative of the black cowboys who historically made up some 25% of the industry. In this figure coalesce ideals of social freedom; a man who can overcome nature and abandon civil codes. But this rogue white figure is equally a defender and, as Eric Hobsbawn identifies, ‘the invented cowboy tradition is part of the rise of both segregation and anti-immigrant racism’.

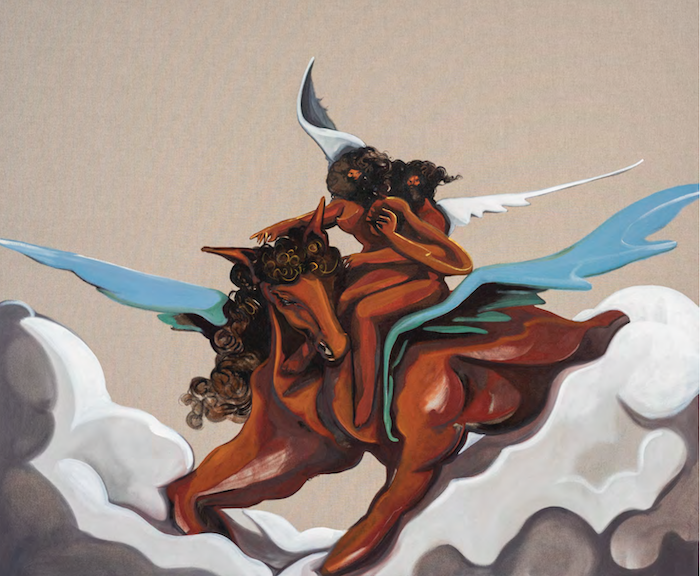

Hoque, knowing too well the implications of such thinking, turns this heritage topsy-turvy and mixes it through with notions of Classical power. His work forcefully exclaims that brown bodies belong in all spaces. Take the rollicking forms in ‘Friends with Benefits’ (2021). They are suffuse with an ancient Greco-Roman essence and infused with the neo-classicism of Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon portrait. The only part of this commission Napoleon directly engaged with was the figuration of the horse: ‘calme sur un cheval fougeux’ (calm on a fiery horse), he stated,

Knowing the animal’s mania would emphasise his clarity of thought and powerful disposition. Hoque’s rearing horse is less an authoritarian prop. It is a companion, upon which two androgynous bodies blend together in a sexually ambivalent embrace. In this flamboyance of forms radiates Hoque’s wish to show the multi-dimensionality of brown masculinity.

Hoque has himself absorbed a triplicate of cultures. His images show his proficiency to code-mix rather more than code-switch. His defiant style takes cues from his early childhood spent living in Rome, his visits to Bangladesh, and America where he now lives. These influences are brought to bear in a work such as ‘Bound 2 Notting Hill’. The statuesque equine has elongated ears typical of a bankura horse, a prestigious terracotta craft produced in the western reaches of India. The exposed linen speaks to South Asia’s fabric trade. And in homage to Kanye West’s song, ‘Bound 2’, whose visuals focus on Kanye and Kim straddle a motorbike and careering into the sunset, his loverboy is the protagonist in this vision of an American dream. Hoque is, at his core, a romantic. Cradled in his cartoon clouds is a softened world where the historic objectification of brown bodies is undone. He’s hopeful this can be less fantasy and more a new reality. —Dr Cleo Roberts-Komireddi

Asif Tanvir Hoque (b. 1991) currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. His recent exhibition's at galleries include, Mindy Solomon (Miami), Almine Rech (Brussels), Yossi Milo (New York), Taymour Grahne (London) and Selena's Mountain (Brooklyn). As a Bangladeshi immigrant, who was raised between Rome and South Florida, Hoque’s paintings attempt to figuratively and stylistically combine aspects of multicultural identity.