Amy Sherald, one of the defining contemporary portraitists in the United States, unveils a suite of new paintings in a major exhibition at Hauser & Wirth London, marking the artist’s first solo show in Europe. Featuring a range of small-scale and monumental portraits across both the gallery’s London spaces this presentation is the artist’s largest to date with Hauser & Wirth. Sherald is acclaimed for her paintings of Black Americans that have become landmarks in the grand tradition of social portraiture – a tradition that for too long excluded the Black men, women, families and artists whose lives have been inextricable from public and politicised narratives. As Sherald says, "sharing these paintings in Europe is an opportunity for me to reflect on how the tradition of portraiture finds continuity as one of several lineages alive in my work."

Sherald humanises the Black experience by depicting her subjects in both historically recognisable and everyday settings, at once immortalising them and reinserting them into the art historical canon. In this new body of work, she continues this practice while confronting the Western canon through allusions to significant historic works or images. This includes the painting ‘For love, and for country’ (2022), a recreation of the iconic photograph ‘V-J Day in Times Square’ (1945) by Alfred Eisenstaedt showing a US Navy sailor kissing a woman in Times Square, New York City as Imperial Japan surrendered in the Second World War. The work deals with the rejection of queer rights to equal participation in public space, as Sherald replaces the white heterosexual couple with a Black male couple in sailor-esque clothing, reminding us of the discrimination against nonheterosexual people within the US military in recent history. The photograph prompted Sherald to think of the Black soldiers who returned from the war, still facing persistent inequities, and what it would mean to broach the iconic pose through another understanding of masculinity. Sherald hopes to offer the viewer a reflection of themselves and the complexities of their interior lives, void of the constructs of race, gender, religion and preconceived notions.

This approach is also exemplified in the painting ‘As soft as she is…’ (2022) which references Giorgio de Chirico’s ‘Lady in Leopard Coat’ (1940), a painting of his wife, Isobella, who is positioned in a three-quarter pose and looks submissively at the viewer. Instead, Sherald challenges de Chirico’s male gaze by depicting a Black female figure in a frontal and confident stance, wearing a similar animal skin coat and looking just beyond the viewer’s gaze, unwatched. A monumental work entitled ‘A God Blessed Land (Empire of Dirt)’ (2022) depicts a man proudly atop his tractor and references traditional farm paintings from the 19th Century which reinforced notions of American identity. Here, Sherald reflects on the history of agriculture in art as well as ideas around land ownership and systematic land loss.

In this exhibition, Sherald plays with traditional American symbology through the portrayal of vehicles such as motorbikes and tractors to engage with the currents of masculinity that underlie the work. As Sherald says, ‘The tractor and motorbike paintings explore different expressions of self-sovereignty in our communities, and how these expressions might carry into the future. Vehicles become a literal metaphor here for forward momentum, for movement and potential movement’. In line with this sentiment, Sherald is interested in the idea articulated by artist Alice Neel that ‘art is two things: a search for a road and a search for freedom’. In a large-scale diptych over 3-metres tall entitled ‘Deliverance’ (2022), inspired by the bike culture that is local to Baltimore in Maryland where Sherald has lived, the artist reflects on the sense of freedom that is part of riding. This work shows two bikers in mid-air, as if suspended in time, in a space free from oppression. For Sherald, the imminent danger of riding and anticipation of death contained in this moment offers a reflection on the ultimate source of temporality.

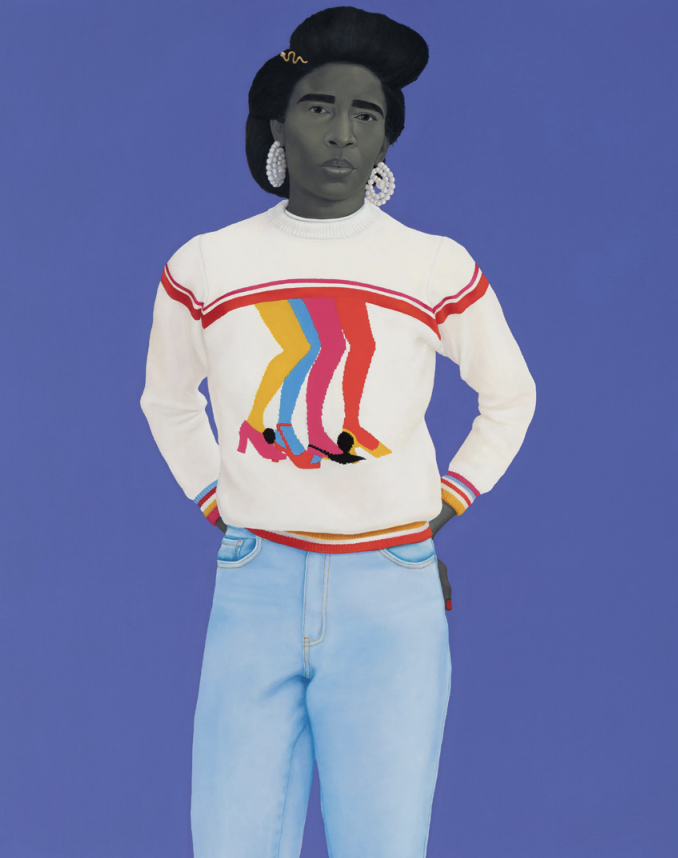

Sherald’s portraits are large in scale but intimate in effect, capturing the ordinary likeness and extraordinary essence of all her subjects while simultaneously detaching them from everyday reality with their bold block colour backgrounds. Despite varying contexts, clothing, expression and positions, the individuals portrayed maintain a persistent sense of privacy and mystery. Perfectly encapsulating Sherald’s desire to draw the viewers’ attention to the sitters’ interior life, hopes and dreams, ‘To tell her story, you must walk in her shoes’ (2022) depicts a female figure against a rich purple background with knitted legs in motion. While her subjects are always African-American, Sherald continues to render their skin-tone exclusively in grisaille – an absence of colour that directly challenges perceptions of Black identity.

Sherald foregrounds the idea that Black life and identity are not solely tethered to grappling publicly with social issues and that resistance also lies in an expressive vision of self-sovereignty in the world. Sherald says, ‘the works reflect a desire to record life as I see it and as I feel it. My eyes search for people who are and who have the kind of light that provides the present and the future with hope.’ The painting ‘Kingdom’ (2022), showing a young child at the top of a slide, both asks us to look positively at future generations whilst reminding us of the transient nature of childhood and the vulnerabilities inherent to it. The title of the exhibition, ‘The World We Make’, is a meditation on, as Sherald says, the fact that ‘as we walk beyond what we have been living through, we have a world to remake’, a message that at once contains hope, while suggesting there is work to be done.