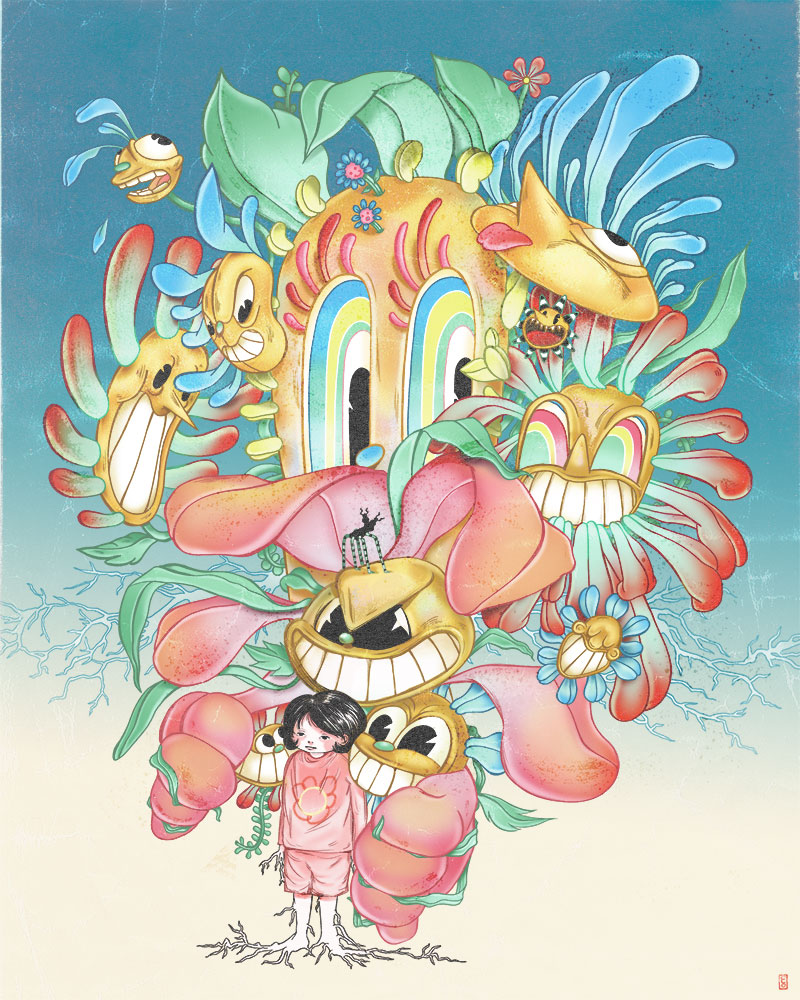

“I think, in its purest form, my art is a visually tangible expression of inner emotions and my ways of coping with life and experience,” Seneca tells me over Zoom one morning, and the first thing that I thought to myself was the struggle she must have found herself in while balancing commercial art with ambitions of studio practice. Pragmatically speaking, Seneca was on top of the world. Garnering illustration awards and lead designing the infamous NFT, Bored Ape Yacht Club, the Chinese-American was representative of a new world of art and accessibility. But sit down with collectors of the BAYC NFTs and ask them to name the designer. Would they know who Seneca is? That is the conundrum of designing one of the most famous icons of the decade: it was just that, a design project. Seneca wants something more.

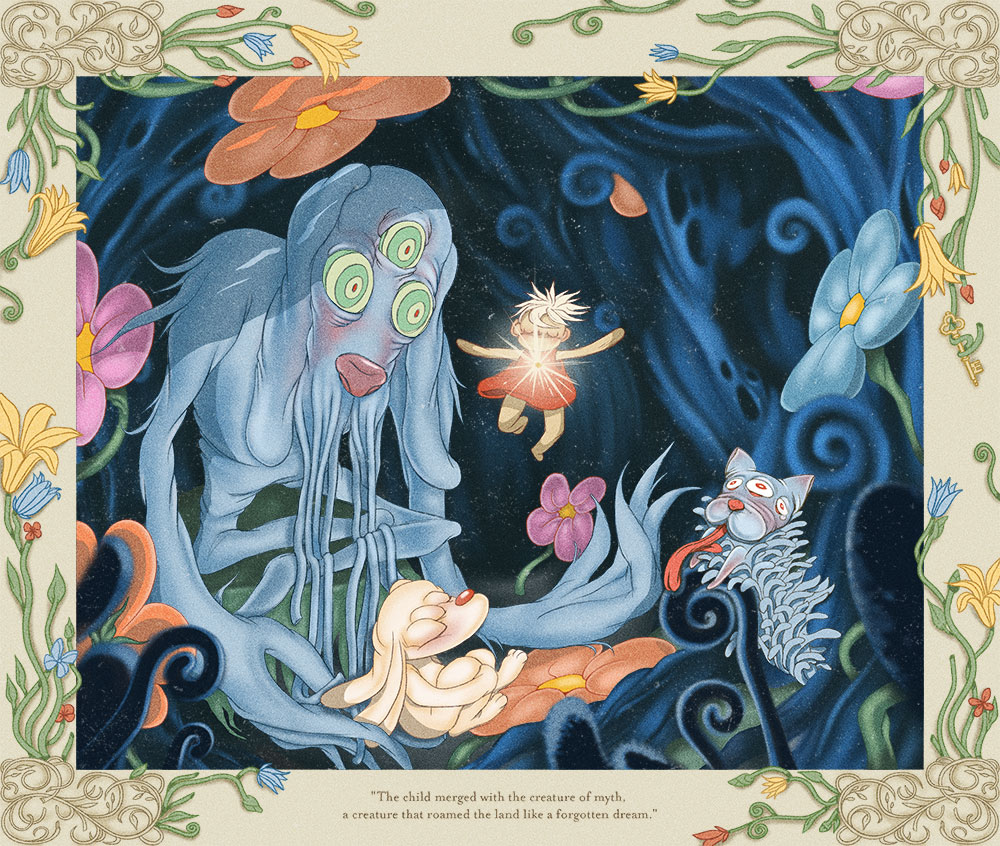

Perhaps this hidden notoriety gave her something less accessible: time. In the last few years, Seneca has been able to build a more traditional practice, placing her on the forefront of multiple worlds of fine art painting, digital practices, and commercial designs more in line with her interests and wonderfully twisted dream worlds that resonate no matter the platform. We spoke with the All Seeing Seneca (as described on her website) and learned about growing up in Shanghai, character design, and how some things just fizzle out.

Evan Pricco: We should start with the direction your career has taken, from commercial illustration work to your current focus on a more personal, fine art practice.

Seneca: I went to RISD and studied illustration because every bit of work that I had done before then slotted into that genre. I guess, in my head, practically speaking, the fine arts industry was something that was very daunting. But in order to make a living, I think commercial art was the right route to go and pursue. I really love design challenges and art direction, so I wanted to work in that field. And to your point, honestly, if I could have just made a living and been able to just draw for the rest of my life, perfect. How could I ask for more? You know what I mean?

But the thing is, I had noticed that every time I continued to push my personal work, I would get more and more opportunities. I had solo shows back when I was a commercial illustrator, and that shocked me. And of course, no one could purchase the work because it's digital art, though now that stuff has changed and there's a cool new technology named NFTs. But it was always in the back of my head. Working as an illustrator was difficult, and I had definitely gained some success in terms of recognition and career accolades. Great, but money was tough. I didn't have a savings account until two years ago, basically. And then when this opportunity arose where I could go all in on my personal work, I jumped on it. Definitely a riskier route, but it's once in a lifetime.

So when we say digital practice in this interview, 50% of the audience will know exactly what you mean, and I would argue that 50% would be a little in the dark, so to speak. Why don't you, in the simplest way, explain what your digital practice is?

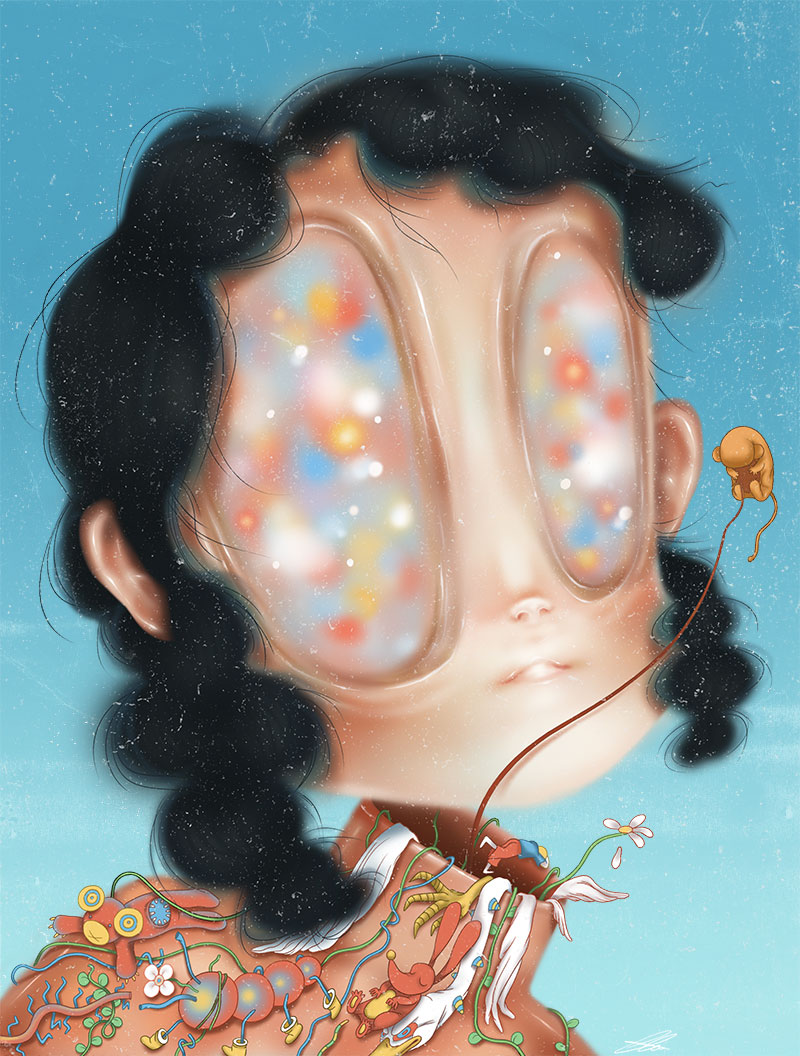

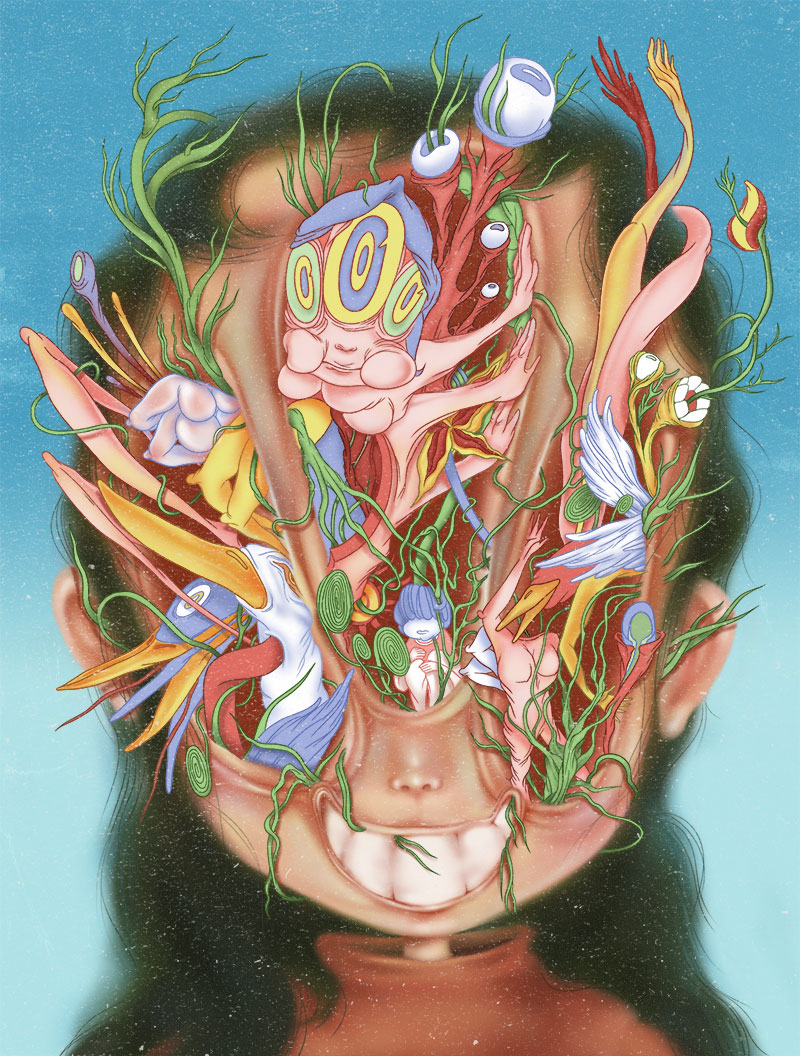

It’s very similar to just sketching on paper and applying that to canvas. Only you're doing everything digitally native. So when people go, "Do you have physical sketches?" I'm like, "There are sketches. They're just in Photoshop, and they should be viewed the same way." I just prefer using Photoshop to do it because then I can manipulate and experiment with it and then use that as a guide from my main piece. And also, being on the internet, you're exposed to so many inspirations, just like you would in a library of art books. So when I say digital practice, it's just bringing this new world of technology into art creation.

What is your favorite program to use for digital art?

Photoshop. All the way. I definitely skew more toward traditional illustration. I despise Vector. I'm sorry. Because I have to go through it all.

What would be the gold standard of an illustration project that you would seek out?

The cover of the New Yorker? Editorial stuff, I think, is huge in our industry. Getting a subway campaign—that’s huge. Getting a gold medal from the Society of Illustrators is huge. Once you are known for a style, like doing fashion and getting your illustrations printed on products at a mass level, I think it is also pretty killer. That's when people are like, "Oh, wow, you made it." But I will say what's unique in our industry is that sometimes people get the cover of the New Yorker, and then it just kind of fizzles somehow. I don't know.

Let's go back to young Seneca in Shanghai, which is where you grew up. In the last 10 or 15 years, the Chinese art market has grown, and there's been more access to that market in terms of just viewership and eyeballs. But what was life like for you growing up there?

My parents really made an effort to take me to museums, and that was part of my life. I was really drawn to animation and storybook illustration, obviously, but animation was kind of a rarity for me. First of all, this is China, so it's difficult to access media outside of the country.

I would have scratched up CDs. There was one that was a Pokemon. Every time I would plug it into my PC, I would pray it would work. It would have two episodes of Pokemon in Japanese, so I didn't understand anything. But I ate that shit up. I was like, "This is so precious, and I watched it so many times." Whenever we would go to Hong Kong, I would buy knockoff Disney because they would have knock-off versions, which is hilarious. But then I ended up collecting the actual Disney tapes and such. And exposure to music was the big one.

My dad is a huge classical music guy, and he would play instrumentals for me, which was really, really quite significant in how I develop my work now, as well as how it flexed my imagination as a kid. It exercised it. I would imagine movies in my head with cinematic soundtracks. I would say it was limited, but that made me more appreciative of the arts and challenged me to create my own stories. If I couldn't access what you guys could out here, then I would make up my own. But I will also note that I would travel back to New York during the summers. Watching TV was, honestly, so fun. I would turn on PBS Kids and be so jealous.

So in that sense, you'd go back between Shanghai and New York as a kid, so you were aware of perhaps a little bit of…

What I was missing out on. I was born in New York, and we moved away when I was four to Asia. There's something about individualism here, but in China, being weird and quirky is not as celebrated. You're more pressured to play nice and not stick out too much. Of course, that's changed over time; Shanghai has become kind of the New York of China. But I knew that in terms of developing art and design, it should be out here, and maybe one day I would bring it back home.

We could probably talk for hours about this subject, but why now start painting in a more traditional sense? What was the change you wanted to see in yourself?

I've always painted. That's never been a stop-and-start kind of deal. I think that when you are so deep in the hustle, you don't have the energy to do other things. And also, when you live in a small New York apartment, having a large canvas in your place is not the most practical thing. But the thing is, I guess, it was during COVID and quarantine that I really reignited my traditional work because I got really sick. I guess that was sort of the catalyst. I got tired of the hustle and feeling a little bit helpless, even though I'd gone so far, but yet it wasn't progressing the way I wanted to.

I really miss being messy, and I need to experiment more and go back to my crafty roots, being an art student and not worrying about perfection. And so at that point, I was like, "I should probably start painting again." Although that's always in my head, I've never really stopped, actually.

I think it would be remiss to go this far into a conversation and not mention something you created that is, literally, world-famous—the Bored Ape character. This could arguably be the most famous NFT collection ever.

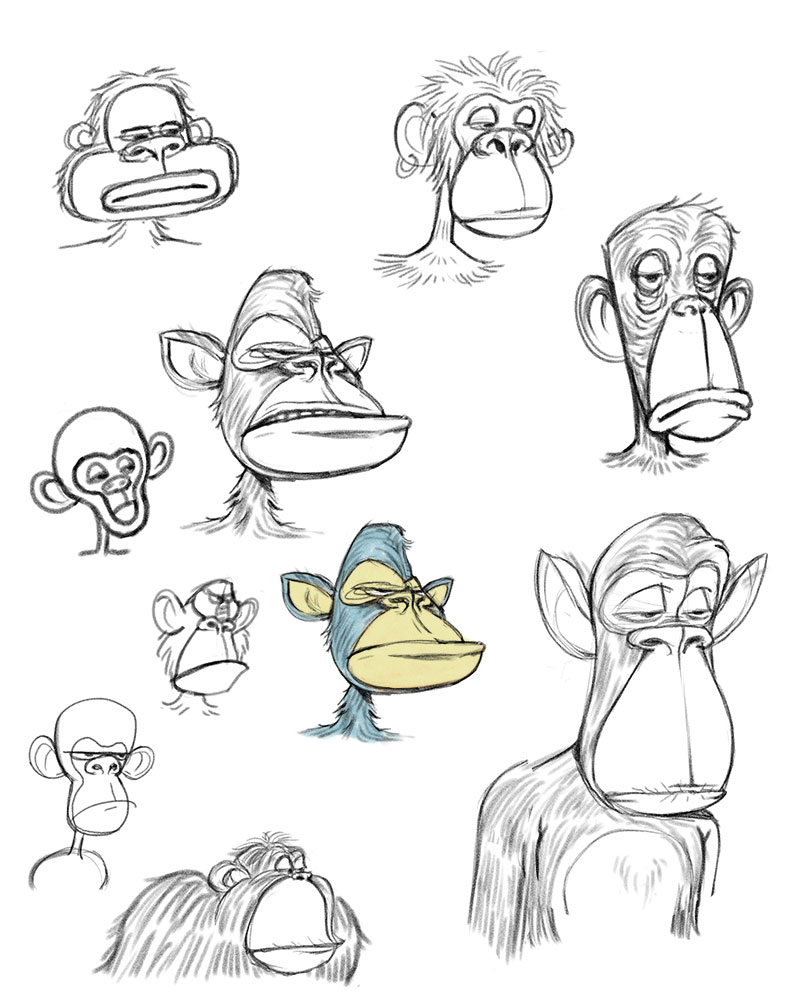

So during my career, I knew I had to keep pushing whatever portfolio I had and keep introducing new skills so that my potential employers knew I could do a lot. So I considered dabbling in the animation industry, which I had not entered before. I wanted to develop a visual development portfolio, which means that you're developing characters, environments, and parts of the story like a story artist.

I created a character design portfolio, and then a longtime client whom I'd worked with for over five years decided to start hiring me for that. I ended up getting referred to those founders, which is Yuga, and they presented me with this idea, to which I was like, "Well, I..." They said NFT and understood the gist. I didn't know too much about it. I was like, "Well, the bottom line is that it's a character design job, and that's what I do. So let me help you." It ended up being a collaborative process, and I made that character, and it kind of went...

I think it's fair to say that whatever we create, even if it's for someone else, is our interpretation of the story. So, for example, the Bored Ape character, they basically keyworded punk apes. And I thought to myself, "Well, I'm a metalhead. I love grimy bars. I'm very self-deprecating." I had just imagined this ape who was super wealthy and had all the time in the world but didn't feel the passion for this work. He was kind of like, "What the fuck am I doing?" And he's sitting at a metal bar. That's how I saw the character and was like, "Okay, if I were a bored ape, I guess crypto millionaire, what would I look like?"

Do real people, like people you know, show up in your character designs?

I can think of an example where another artist would do this: Maurice Sendak (whom I love) said that his wild things in Where the Wild Things Are are actually his family relatives! He said his aunts were like monsters trying to squeeze your cheek or kiss you when he didn't like it. I can tell interviewers squirm around this answer because they're unsure if they should get into that with him or not, whether it was trauma or if he just liked to be a troll.

I think there's no doubt that there's some semblance of real people in my work, but I prefer to represent them more abstractly, perhaps less willing to explain it so black-and-white, and a way to do that is to take the human form away. I usually make them plant life forms or something organic, just not humanoid. So rather than me telling you, "Oh, these represent my family that made me feel burdened with their expectations," it's "the plants should feel overbearing and tremendous and almost claustrophobic." We’re focusing on the feeling most of the time.

With commercial art, fine art, and even the NFT projects you have been part of, there is no limit to the accessibility and approach a collector or viewer can have with your art. But where are you most happy to see your work?

You know what? I would like my work to become more accessible at some point. Having one painting, there's only one version of it, but I'd rather have kids see my work in a book somewhere or on a product that they really treasure. I think a lot of that is looked at as low-brow or more commercial, but I still have an appreciation for that. Just making art that’s integrated more into the culture than some dusty painting in someone's basement.

Allseeingseneca.com // This interview was originally published in our WINTER 2024 Quarterly