Soul of a Nation

Art in the Age of Black Power

Interview by Gwynned Vitello

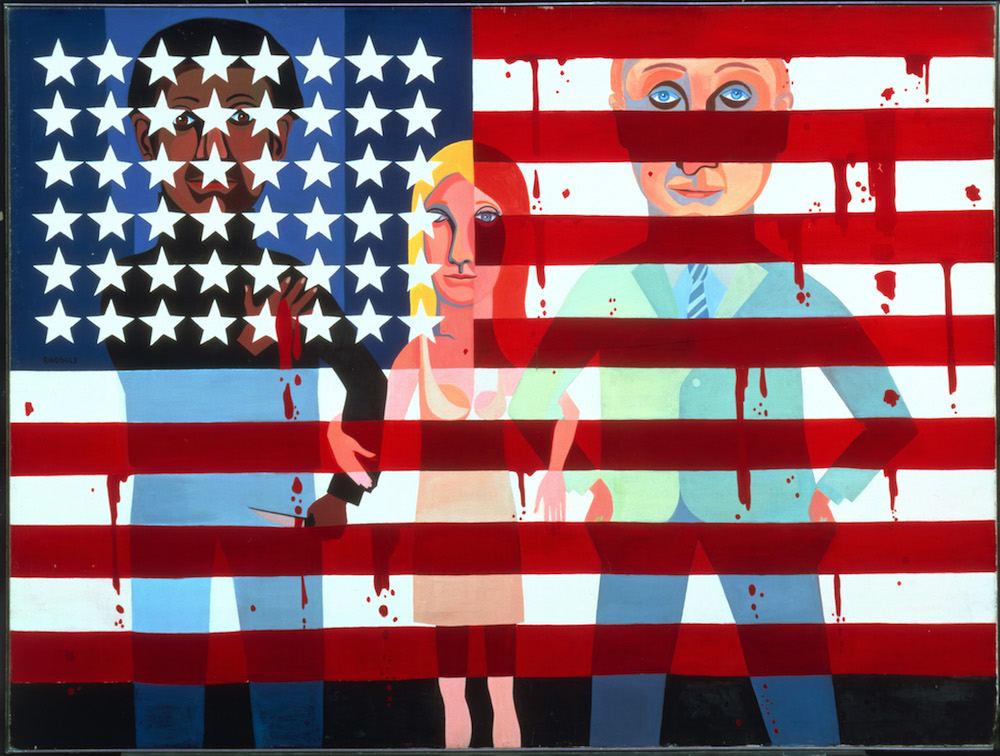

Painter Charles White, celebrated this year in a series of retrospectives, recognized the power: “Art must be an integral part of the struggle. It can’t simply mirror what’s taking place. It must adapt itself to human needs. It must ally itself with the forces of liberation.” He is among scores of African American artists featured in Soul of a Nation, the blockbuster conceived at London’s Tate that testifies to the tumultuous pre-shocks that trembled through the 1960s to the early 80s. It’s a show about potential, urgency and dignity, and about a practice that White described as, “The challenge of how beautiful life can be.” I learned more about the artists in speaking with Tim Burgard, Curator in Charge of American Arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, where the show opened November 9, 2019.

We’re the fifth venue, and the first signed up by our director Thomas Campbell. This was a high priority for him to move mountains and make this exhibition happen on fairly short notice, and absolutely every staff member jumped on this to make it happen to our usual high standards. Everyone knows how important this is. I think it’s very telling that so many artists are making the effort to attend, finally getting appropriate recognition for their accomplishments. Several, like the brilliantly endowed Barkley Hendricks, passed away during the run of the exhibition, but we do have his painting What’s Going On, maybe the iconic image of the show.

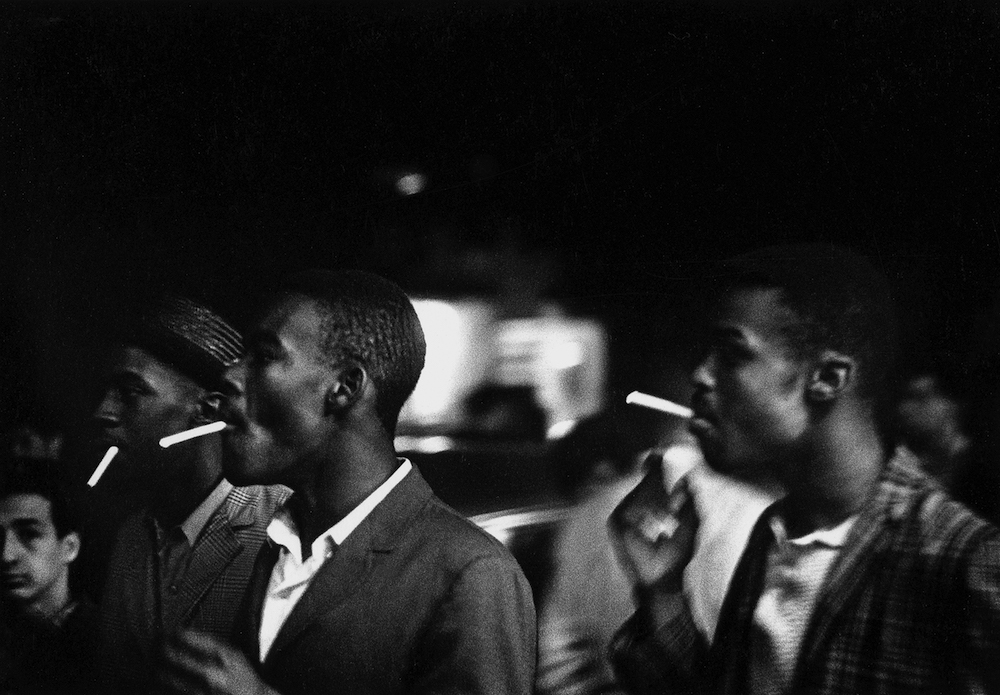

“In the 1960s, America was fucked up and didn't see what some artists or what black artists were doing... My paintings were about people that were part of my life” –Barkley Hendricks

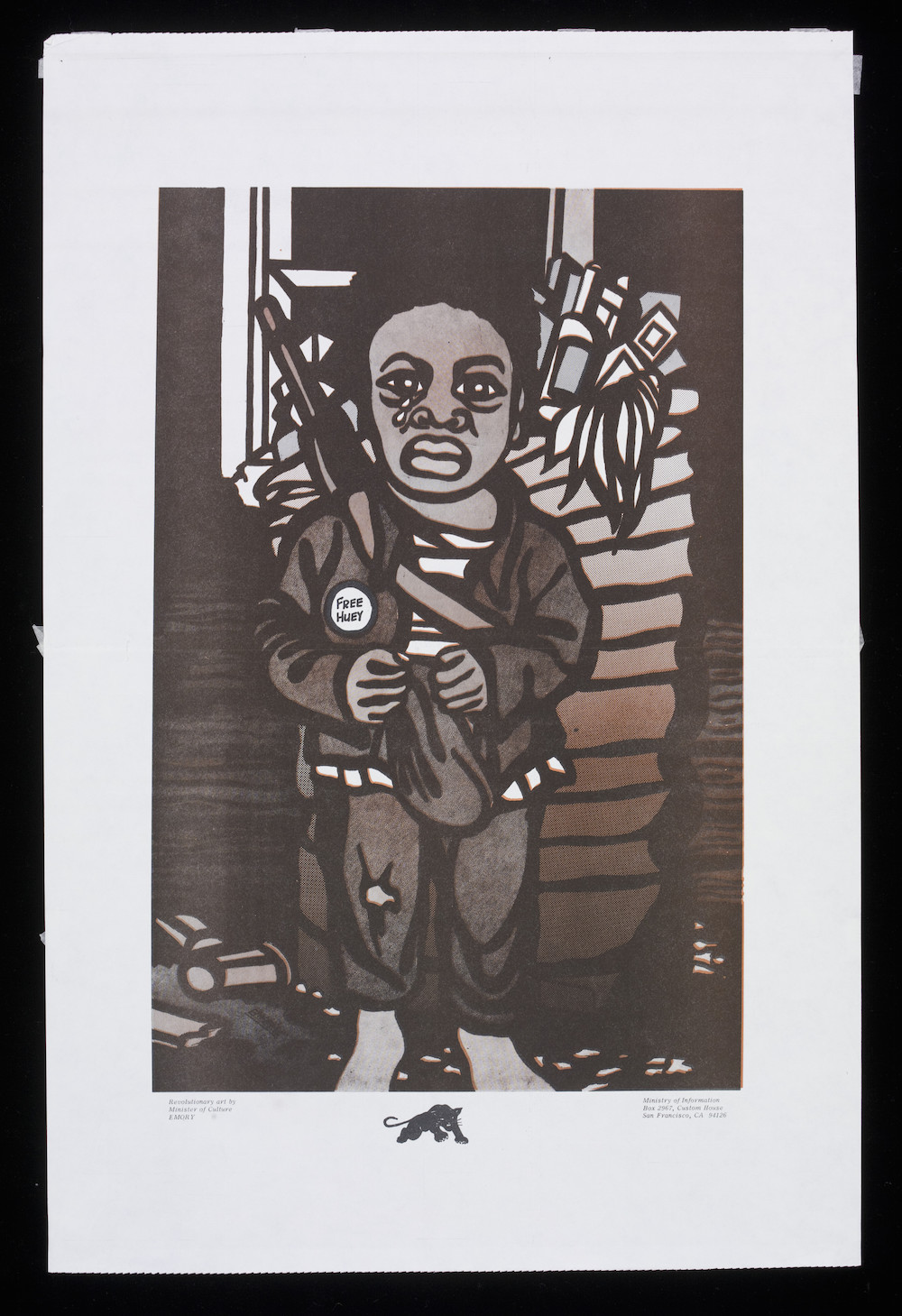

“The ghetto itself is the gallery for the revolutionary artist.” –Emory Douglas

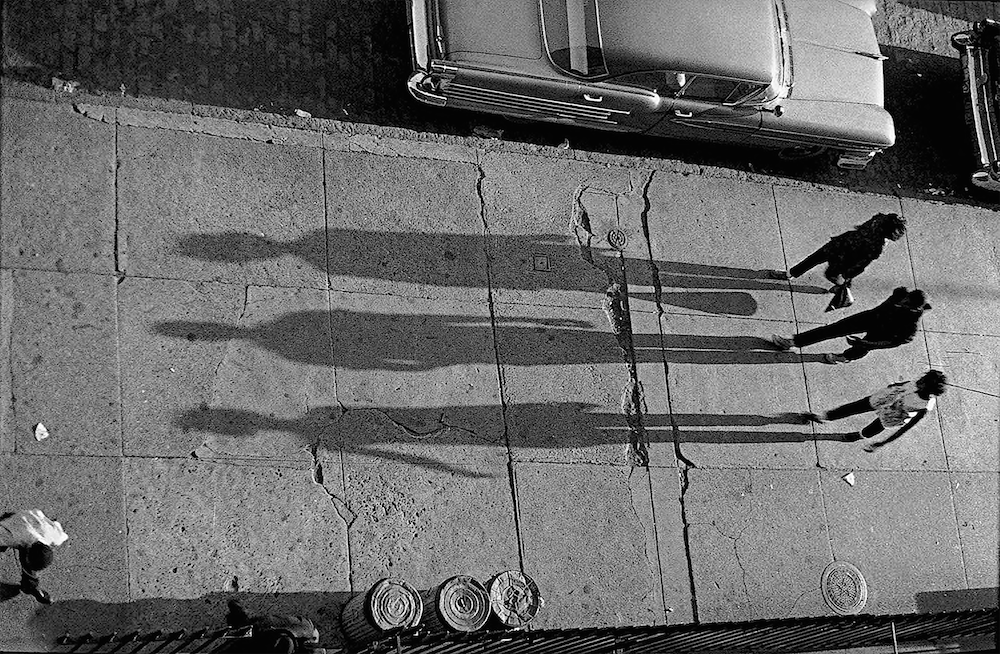

“There were no black images of dignity, no images of beautiful black people. There was this big hole. I tried to fill it." –Roy DeCarava”

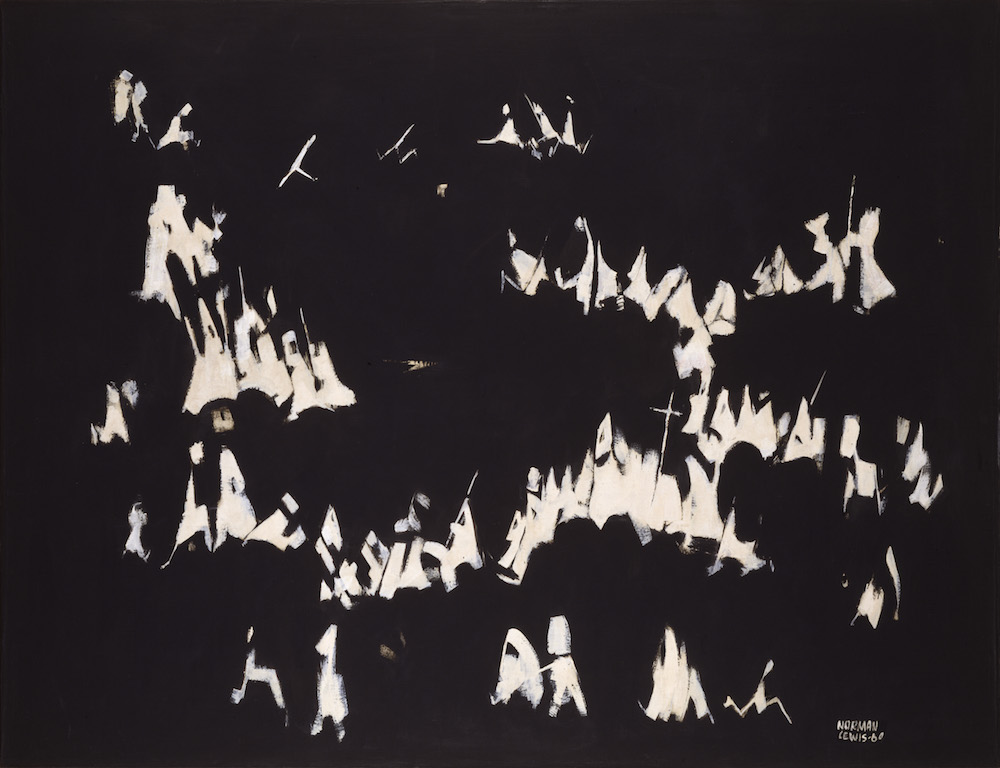

“I just hope I can materialize something out of all this frustration as a Black artist in America." –Norman Lewis

“Every work of art has a moment, has a time... there is nothing like a work of art.” –Sam Gilliam

“It was not just a fight being a black person in a white society. It was also a fight being a poor person in a total society.” –Benny Andrews