Nat Meade

The Evolution of Man

Interview by Sasha Bogojev // Portrait by Cary Whittier

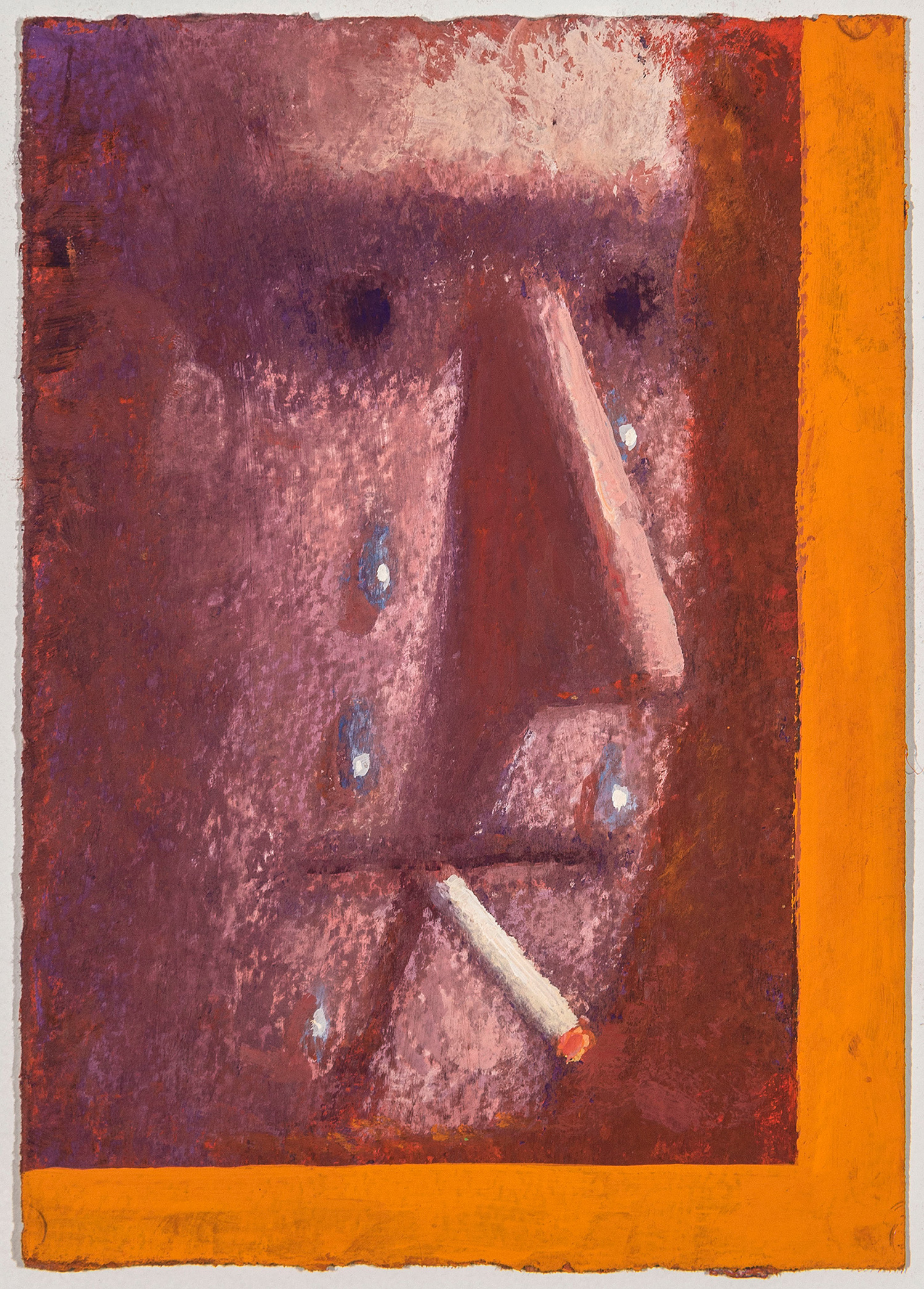

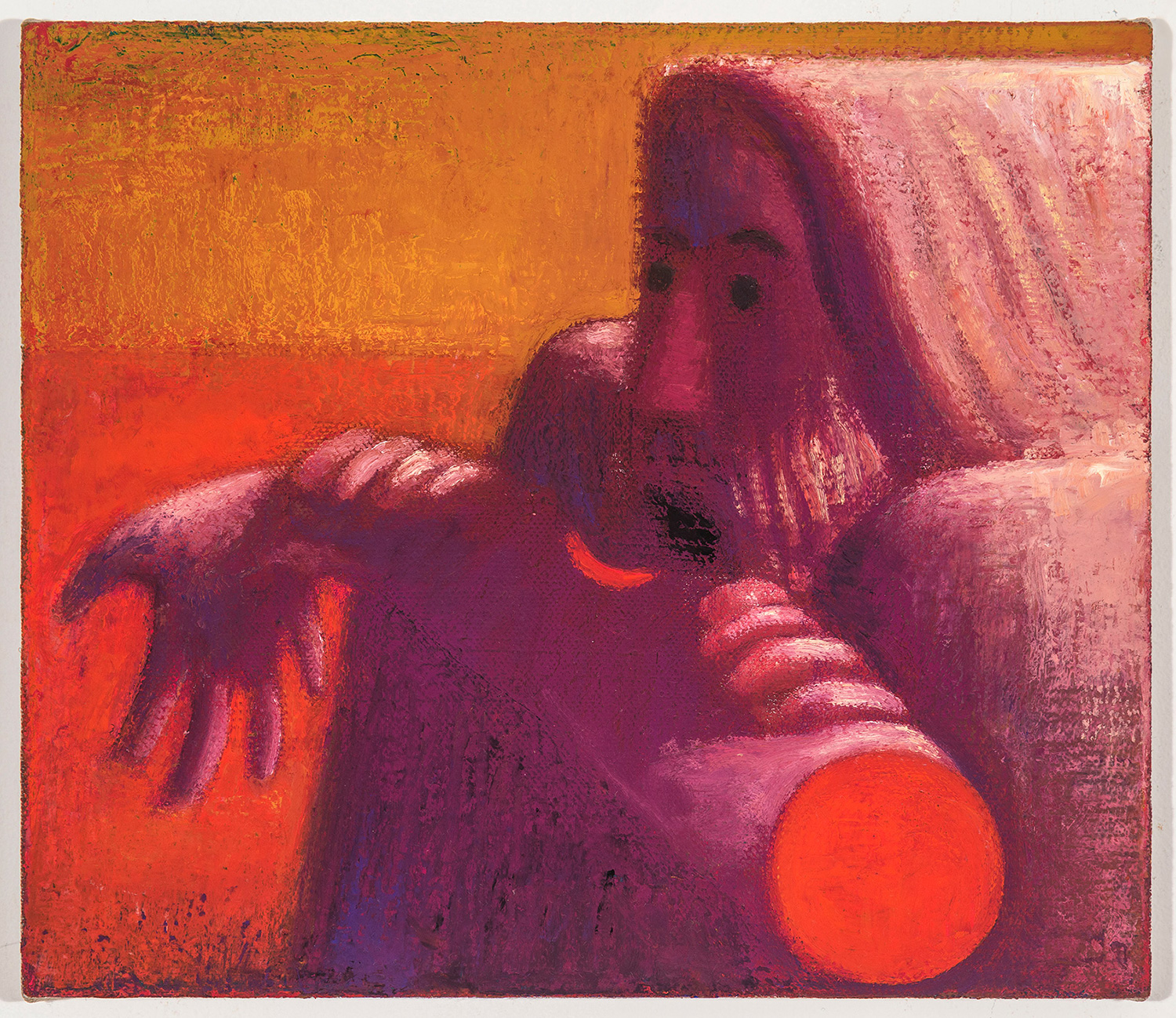

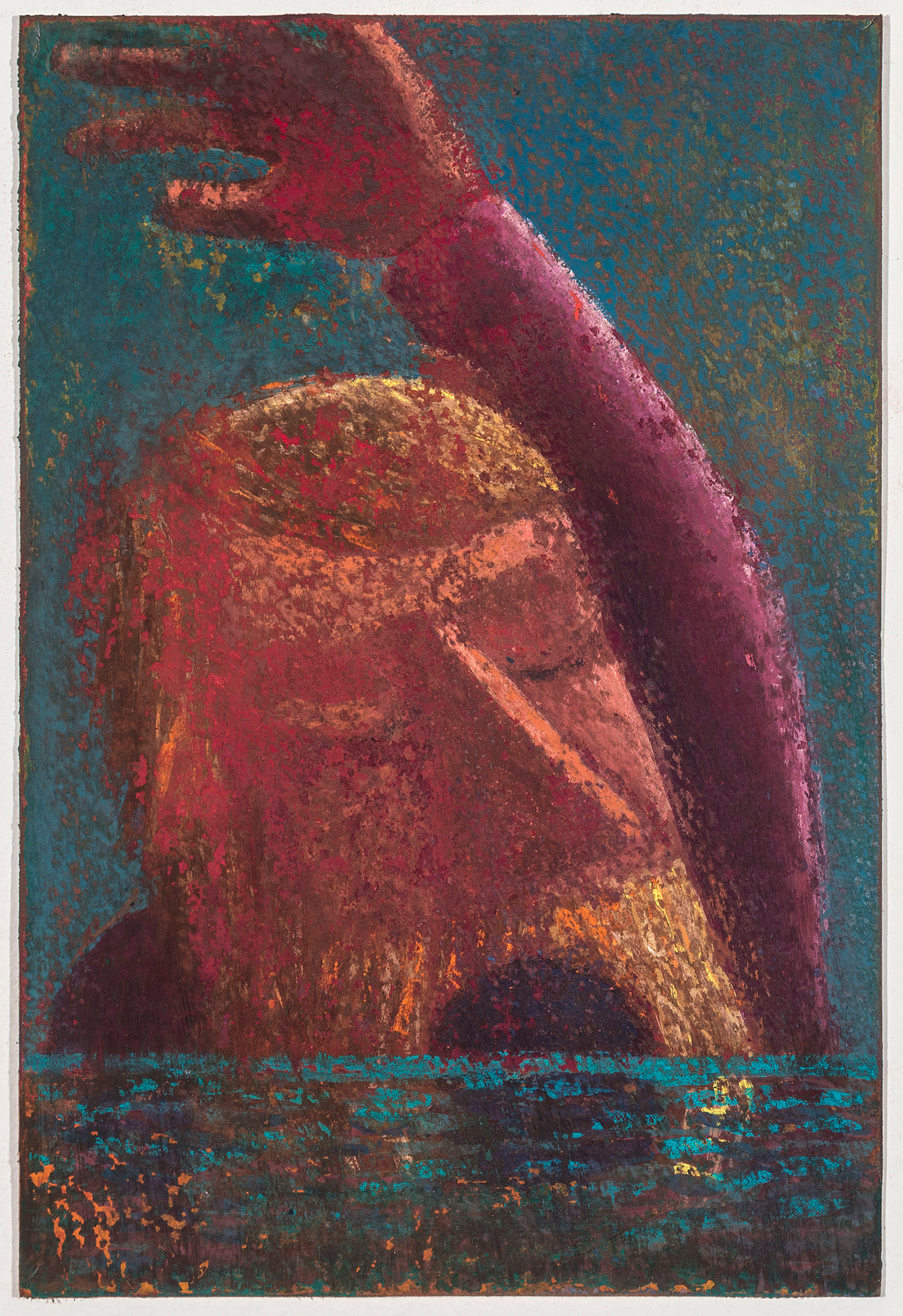

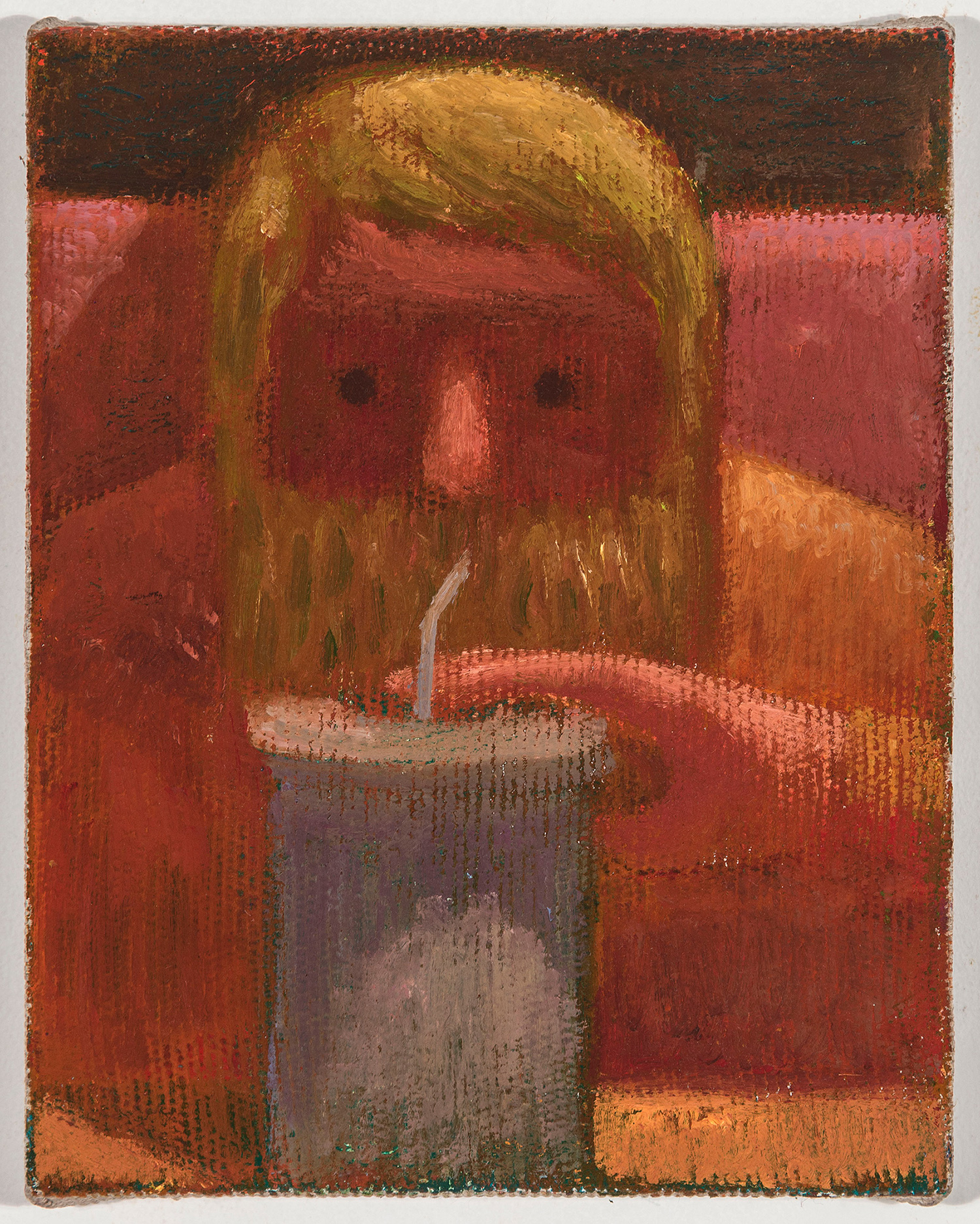

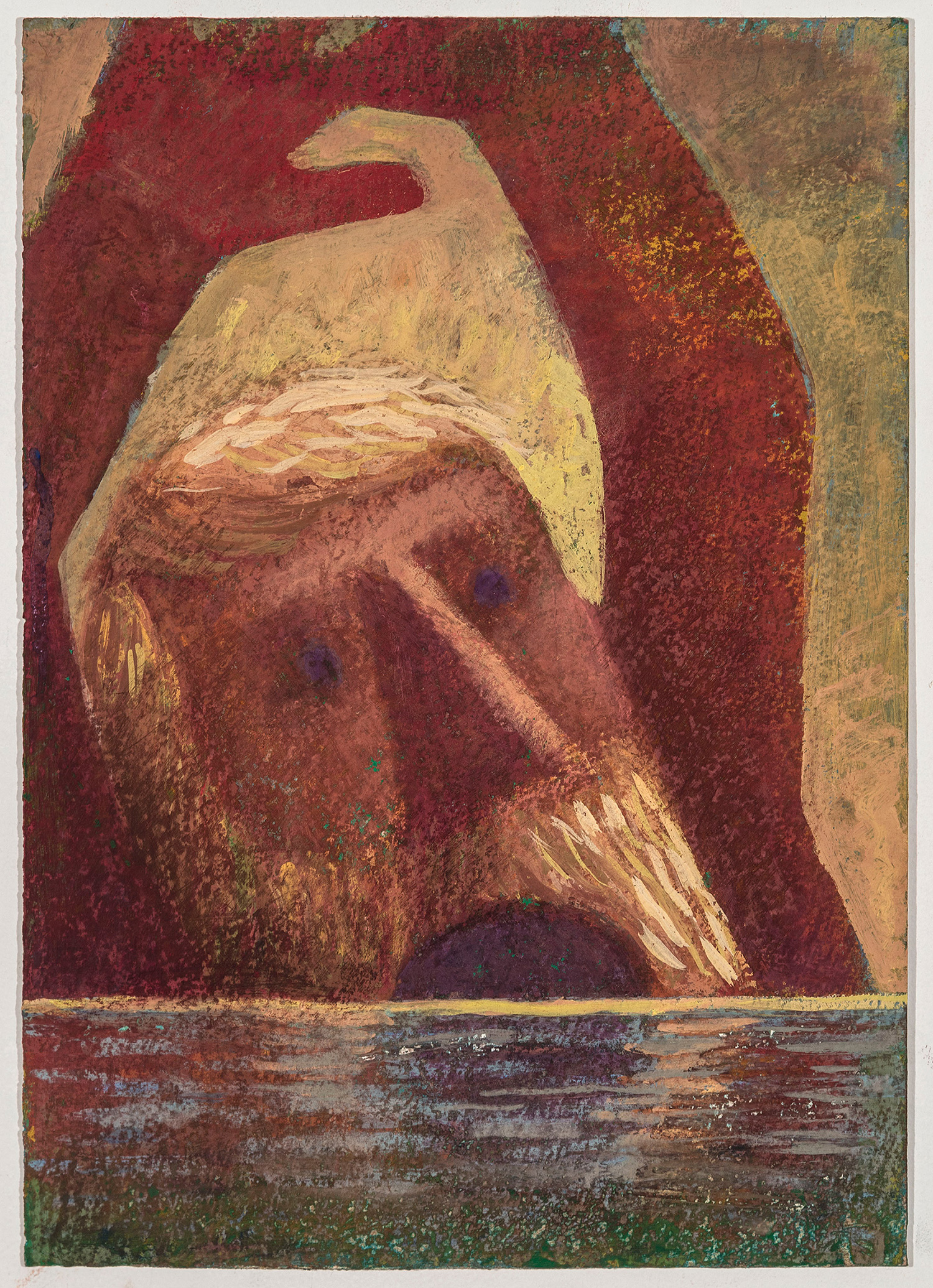

When you can describe your creations as “gods and buffoons,” it’s clear you’re drawing with a broad stroke and scope. Nat Meade embodies a uniquely dedicated approach as he crafts an almost anthropological personal view of society. Each small-scale portrait captivates with familiarity in a nuanced portrayal of the masculine archetype. Signature strong facial lines, beards and Roman noses are enhanced with everyday accessories that ground them in approachability. Stoic portrayals in muted colors, bathed in directional light and shadow, deconstruct the man-father-god as humanity emerges, one small canvas at a time.

Sasha Bogojev: Why don’t you introduce yourself to us?

Nat Meade: I was born in Massachusetts. Both of my parents worked at a boarding school there. I moved to Portland, Oregon, at a young age. Portland was an interesting city to grow up in; not yet on the map as a hip destination, but very eccentric, and there were lots of creative people around. I was artistically inclined and enjoyed drawing. I didn’t like going to school and did not excel in school, but I enjoyed drawing, and teachers recognized this ability. I remember taking a taxi across town to a talented and gifted program where I studied drawing. I took classes at the Museum School (now PNCA), which led to me being chosen for a trip to Japan with other young artists and musicians. My parents introduced me to interesting music and art—Raw Vision, comic books, and yearly trips to MoMA, the Met, the Frick and the Whitney when we went to New York to visit my mom’s family. I also discovered Dark Horse Comics, a local source of pride.

You started early.

I am a big guy and excelled at football and basketball, so later took to sports in high school, which wasn’t a conflict with art until I went to Boise State University on a football scholarship. I later transferred to University of Oregon to focus on painting and found my mentor, Ron Graff. Ron really taught me to see and introduced me to so much. After a few years in Portland, I moved to Brooklyn to go to graduate school at Pratt Institute.

I worked primarily with professors Joe Smith and Nancy Grimes at Pratt, and that was a great experience for me. Now I split time between my family, teaching, and administrative work at Pratt. I have been intensely focused on developing as a painter since graduating from University of Oregon.

How was moving to Brooklyn an influence?

Moving to Brooklyn opened my eyes. I went to shows all the time in graduate school and really tried to find the artists whose work resonated with me. I quickly learned what was out there, and how singular, unique and varied contemporary painting could be. Early on, I wanted to do it all, and my work would change according to the artists I was looking at. It is not the best way to work, but you get something out of each experience. Eventually, I started to stake out my territory and prioritize what was important to me. I found my influences and would build on what I could learn from their work. Then, in 2009, I went to Skowhegan and I began to zero in on this thing I am doing now. So, Brooklyn has been about exposure and influences and finding my own path—also realizing I have something to say and could play ball. I am wrapping up my one-year stint in the Sharpe Walentas Studio Program. It has been amazing.

Who are the guys, and it is mostly guys, that you portray in your work?

In terms of identity, we are searching for something authentic, and at the same time, open and interchangeable. It is so tenuous and elusive. I want my guys to be difficult to pin down. In one sense, they are meant to be ridiculous buffoons, wide-eyed mouth breathers. Similarly, I think about evolving (if you can call it that) male roles, changing notions of what it means to be male. This is nothing groundbreaking or new, and I am not interested in specifics or anything topical, but I do think about these changing notions of masculinity. My figures are caught unaware, somewhere in the middle.

The built-up paint and worked surface, directional lighting and stoic forms imbue these dummies with a sense of reverence and history, so one read undermines the other, and hopefully, empathy develops in this cycle.

So—gods and buffoons.

What do they represent for you personally?

They represent different notions of men. I like that a beard can be current or associated with many periods throughout history. I am certainly not interested in satirizing hipsters but I don’t mind that this is one of the reads. I pull from lots of different things; movies, archival footage, historical painting. Like that heroic Grant Wood painting of John Brown, wide eyed, mouth open and raging. This painting is certainly an inspiration, but, in my version, the vulnerability would be apparent and the heroism lost. I love the characters from movies of the 1970s, which was the era of television that I grew up watching as a child of the 80s. These were the reruns of movies that were on TV on a Saturday afternoon. With the strange clothes and grainy Technicolor, I found them so visceral and mysterious.

You often revisit recurring images of glasses, beards, and cigarettes, for example.

Glasses, cigarettes, collars, and beards humanize the figures, grounding them in our world, but are open-ended enough that the viewer can bring their own associations and projections. They imply things about the identity of the figure but are not tied to a specific individual or time period. We have our own associations and can project from our own experiences.

These props also present painting opportunities and challenges. I can play with the cast shadow of the nose or collar, the transparency of glasses, the scrim of smoke, or the pattern of a beard. I like working with directional lighting and figuring out these moments. What would happen if light passed through these glasses, or through this scrim? The illusions are imagined and metaphorical. There is something both challenging and amusing about these moments.

Speaking of beards, there is a pretty interesting connection with your work and Walt Whitman, right?

Yes. I grew up with an Antonio Frasconi woodcut of Walt Whitman in my childhood home. It was an amazing but simple image, dark spots for eyes, a series of dashes for the beard, a triangular form for the nose.

Images you live with can really weigh heavily on your psyche and imagination. This was my god-figure, what I saw when I imagined a god. When I did something wrong, this figure would come to me in my moral dilemma. I also thought it was my dad, so obviously, father and god were closely linked. I recently discovered that my brothers also thought this picture was our dad.

My work touches on this process we all go through, elevating the important male figures in our lives, especially when we have to make sense of things as kids. As we grow older, we see their vulnerability and imperfections and recognize our heroes for the flawed individuals that they are. At best, we realize the difficulties that life presents as we develop understanding.

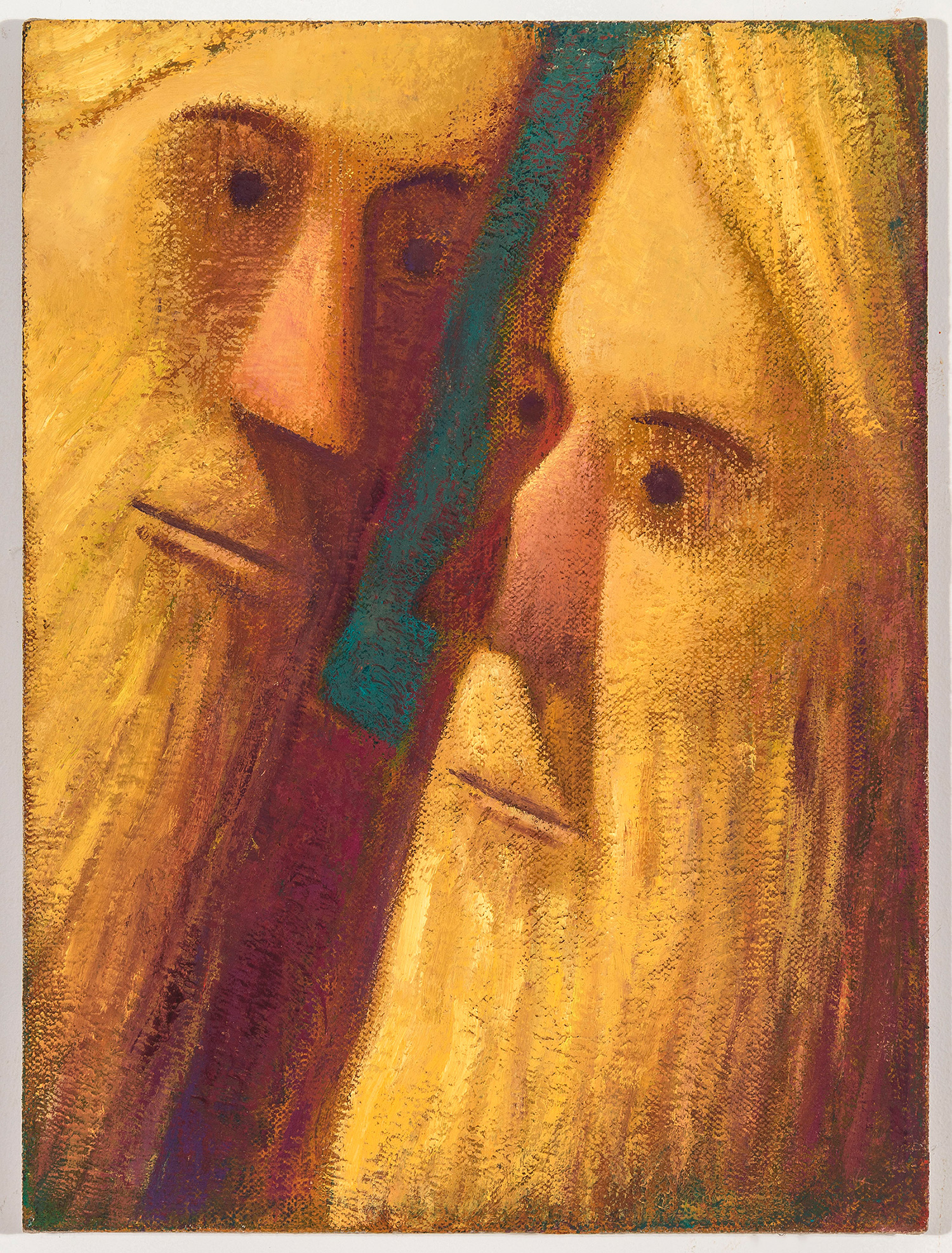

You often paint multiple iterations of the same composition, and the same image. What’s the idea behind this process?

For one, it is difficult to come up with ideas and motifs that are meaningful. I spend a lot of time thinking about what would make an interesting, meaningful image. When I do come upon something satisfying, I have a hard time letting it go. I want to explore the possibilities.

I work through an image or loose idea, like two faces looking at each other. I knew I wanted to have two bearded faces very close to one another with one face casting a shadow on the other. I worked through several iterations of the this relatively simple image and idea, changing the color, scale, and verticality of the canvas. As I paint, the image changes a great deal. With each version, I get a little closer. With a new painting, I start where the last painting left off and see where it goes.

Do you work on your paintings one at the time?

I work on maybe a dozen paintings at once. I do a lot of scraping and covering. I build up underlayers and need to wait for the paint to dry. So, when a painting gets to a point where I need to leave it alone to dry, I can jump to something else.

Prior to that, you're also making a couple of different studies as a reference to begin with, right?

I start on paper, so I can work quickly and make changes. Casein dries quickly and allows you to cover up and make fast alterations. I spend a day or two with the works on paper. I do a lot of sanding and wiping out, but, through this process, the composition and image clarifies and reveals itself. I pin up the works on paper and they become the starting point for my paintings. As I said, each new painting informs the next one.

It feels like working on a computer and trying out different things, but in an analog way, without the power of an undo button, would you agree?I don’t think so. I have never really drawn on a computer. The thing about making changes on the work is that it creates a physical history. I can cover with paint and scrape down to a phantom image. This phantom image and history really informs the final outcome. I can set things back, lose the image a bit, and make changes, but each decision helps to create the physical surface and complexity of the painting. There is a physical push and pull. I can’t imagine working another way.

I’m wondering if you have moments when you think, "Yup, that's it. This one is done.”

One thing I have found is the work usually gets better each time I go in. Rather than getting bogged down, it gets more open, fresher, and more interesting, so I have a hard time letting go. Deadlines are helpful.

From what I’ve seen, this is a unique way of creating work. Do you ever feel like you're stuck, or is it more of a self-imposed restriction in order to progress?

I don’t feel stuck. I like to see where things end up.

Also, working with a set motif or set imagery means I can get started pretty quickly. Then it is about losing and discovering the imagery and finding something new and surprising within the set parameters.

The hard part for me is finding a new image to kick around. I sketch very loose arrangements and will watch movies with the sound off. I am trying to find something new and meaningful. The work that comes from this process might not resemble the initial image or sketch. I am looking for an idea, looking to plant the seed that will yield a lot of new work.

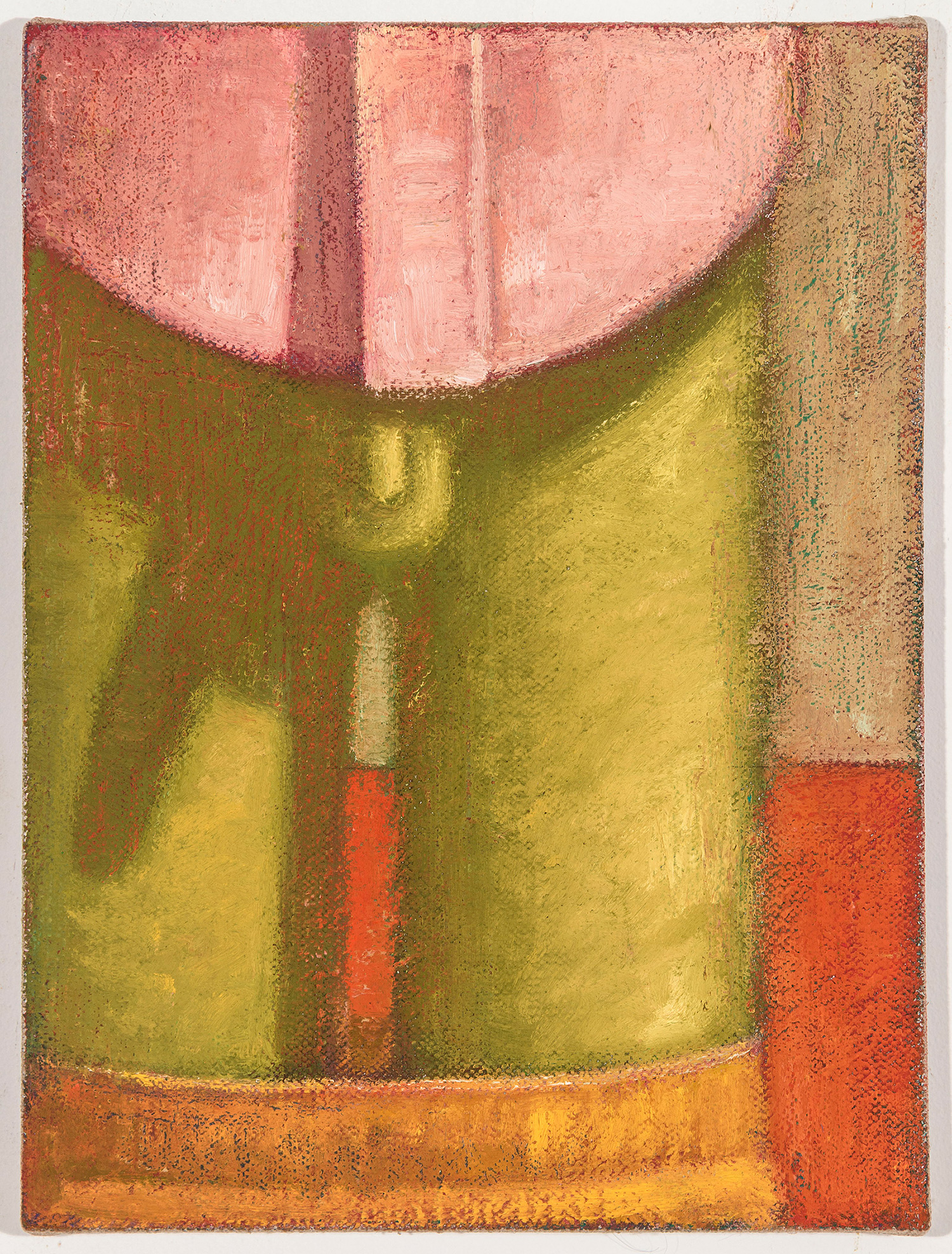

What about the more abstract works? What do they represent?

I have done some still life paintings recently, overhead views with strong directional lighting, and also some closeups focusing on clothing and body parts. These are similar to the heads—geometric compositions with minimal context, open-ended indicators, parts but not the whole.

I would like to do more of the still life paintings, though it’s harder for me to invent a still life painting like I do the portraits. I would like to do a series of overhead still life paintings working from direct observation, or at least started from observation.

Are there any other concepts or subjects you want to try out, or any you are already experimenting with?

Definitely more still life paintings. I want to do a series of objects in boxes and would want to work from life. As I mentioned, I used to have all these collections that I kept in boxes. I used to lay them out on my bed, boxes of agates or railroad spikes. I would like to recreate that moment. I have been working on a still life of a box of condoms and cigarettes. I definitely had a box like this. These paintings would be about this transitional time.

Are composition, texture, and color scheme equally important to you?

Texture and color are, of course, important, but composition is paramount. Color and texture are byproducts of finding the form and composition. I realize there is no hierarchy between composition and image. They are totally equal. I really enjoy imposing the composition onto the image and vice versa. Light is also an important player, and I work with light in a similar way, where it takes on an almost physical quality creating these strong diagonals that run through the work. It becomes a compositional and allegorical device.

Your color palette feels purposefully limited as well. How often do you introduce a new tone into the mix?

My work starts out very colorful, like every color on my palette, and then the color is reduced. I am always thinking about how colors will reveal themselves as the painting evolves. I do lots of scraping, so lots of the early colors are apparent. In terms of the palette, I use bright colors but want the image to feel distant, faded or set back, so I use a lot of hazy pinks, golds and greens. I like to make an almost completely yellow painting and sneak in a little area of purple or a pink nose. I also want to avoid muddy darks. I want everything to have color. Pink and yellow are good for giving the painting a sense of light throughout.

I work on rough surfaces. I like that they keep things open and general. I have a tendency towards detail, but the surfaces don’t allow it. Only after the painting has been worked over a bit can I add detail. I start out with a lot of paint, working generally. As I mentioned, I tend to paint things out and find them again. I often scrape out parts that I want to recede or scrape out the whole painting if it is not working or needs new energy. I do a lot of painting out and painting over. This process yields a unique surface. Maybe a little fussy, not much bravado or swagger, maybe an antiheroic surface, but it goes with what I’m after.

Basically you earn your chance to get detailed. How long does it take to finish a piece from the moment you start painting on canvas?

Weeks to months. It really depends how things come together. I feel like when I go into a painting, it tends to get better. This is a bit of a curse and can mean that I spend a lot of time with a painting. There are little paintings in my studio that I have been working on for months. This is not to say that I work on them every day. They sit around for much of this time. I am often waiting for paintings to dry. There are a couple of paintings that I have been working on for years.

natmeade.com