Calida Rawles

Wade In the Water

Interview by Kristin Farr // Portrait by Glen Wilson

A Dream for My Lilith was 2020’s most talked-about West Coast exhibition, the first solo show for Calida Rawles, whose work took multiple forms until an enlightening deep dive. Water arose as a metaphor for life, death, the ubiquitous unknown, and the universe, and she’s only just begun this exploration.

The paintings Calida made to accompany her friend Ta-Nehisi Coates’s celebrated novel, The Water Dancer, brought her work into the light for many, but her flame has always burned steadily, and she remains in pursuit of beauty among the unease, wading through waters both troubled and calm. “I hope I’m like a visual Octavia Butler,” Calida mused during our conversation, referencing the mind-expanding Afro-futurist science fiction author. Butler’s wise words are a poignant starting point for our conversation during uncertain times: “Kindness eases change. Love quiets fear.”

Kristin Farr: I can’t imagine shelter-in-place with three kids in the house and a studio practice. How’s it going?

Calida Rawles: There’s this guilt of being in the studio that wasn’t there before, because my husband is home with the kids trying to be a teacher and a cook. I actually didn’t come to the studio for a week because I was feeling sick, and I realized it was self-induced. I had no symptoms, but I convinced myself I had the coronavirus, and I kept waiting for it to come. And then I was like, you know what? I don’t have corona. Maybe it was depression that I was feeling, or I was scared shitless and didn’t know what to do. I was in this weird warp, and I had to get myself up, and that’s why I’m in the studio today for the first time in a week. My four-year-old, Siena, was starting to cry before I left. She said, “Mom, I feel like I’m gonna be in the house all day until I die.”

No wonder you feel guilty.

That’s the shit my daughter says to me. My husband’s been really cool about everything, and I’m so happy to be in the studio and out of the house, but then I feel guilty again. So that’s my whole quarantine; a guilt trip.

Can you even go swimming?

No.

Can we ever swim again?

I am. As soon as someone opens a pool, my butt is gonna be right in that water. I need to swim. I am so waiting to get in the pool. I want to make money selling paintings so I can get a house with a pool! That’s my new goal. I always have to go to someone else’s house or public pools. So now I feel more motivated to get a pool. That’s all I want.

I heard you’ve been selling art since day one.

As a kid, I would draw things like Garfield cartoons and sell them for a quarter to my friends. I’d be like, “What do you want, Snoopy?” And I’d write down what everyone wanted, and go home and do a cartoon and put their name on it in bubble letters. That made me feel like I could make money from art, and it was fun to take orders.

Your solo show at Various Small Fires was a huge hit when it opened in February, and then we all had to go home indefinitely. How did that success feel?

Really good. I was very happy the work resonated. I was selling paintings out of my studio for years. They take so long to paint, and I had been working on that show for nine months, and I was so happy with the reception. I couldn’t have scripted it better and I was blessed with the timing. Just one month later, and no one would have seen it.

Tell me about the title, A Dream for My Lilith, because Lilith was an unsung biblical character.

Some girlfriends mentioned the Lilith story to me, and it was fascinating that there was an alternate creation story that I never heard. Lilith became known as the spirit of darkness because she wouldn’t lie beneath Adam. She wanted to be seen as equal, and therefore she left Eden and was punished. Equality is something we should all strive for, and I can’t imagine why we are punished for it, even though it happens all the time. So that stuck with me and made me think of my experience as a black female. She was seen as difficult, and these stereotypes of how they describe her, or how she’s written about, are somewhat like stereotypes of black women. It could be about any woman, but it’s a dream for those who wanted to be seen as equal and were chastised for it.

My 14-year-old daughter, Skye, became a focal point, as I think of her becoming a woman and what that means, and what she has to face, and how people may see her as difficult when she shares how she feels. At the same time, I lost a cousin last year, and we were very close, born two days apart. She had ovarian cancer, and we went on a girls’ trip to Jamaica when her illness was pretty far advanced. I was telling them the story about Lilith, so we decided to call ourselves The Liliths, like descendants of this woman who fought against the grain and didn’t even want to return. She had the option to go back to Eden but said no, that she’d rather be alone than subservient.

When I’d call my cousin, I would say, “How are you doing, my Lilith?” So it was a tribute to her too; the title is multi-layered. My cousin and I grew up together, we had different complexions, and I played with that a bit in the show. The painting, Yesterday Called and Said We Were Together was definitely me thinking of her.

That’s the first painting I wanted to talk about because the title and image felt so meaningful, even more so right now.

I almost felt like I wanted to keep that painting for myself, because she was the spirit of a lot of the show, and I used that fuel and energy to think about sisterhood, and what divides us and brings us together. At the same time, I was working with Ta-Nehisi, reading the different versions of The Water Dancer over and over. It was about family and the loss of family, so thinking about that, while having a personal loss… and then the water being personally very healing, and a visual language that I used to deal with difficult, divisive issues.

I figured out a way to tap into these different types of conversations I wanted to have, but through water. It’s just so beautiful, it draws people in, it makes me want to look at it. I can just keep looking at it, and I can have heavier messages in there, but it’s also very soothing. It just feels like a more comfortable way to address topics. I address all of my problems in the water. If I’m stressed out, and then I go swim, when I get out, I feel lighter, and I’m able to deal with things, and I keep thinking about how I can create that same feeling with images of water.

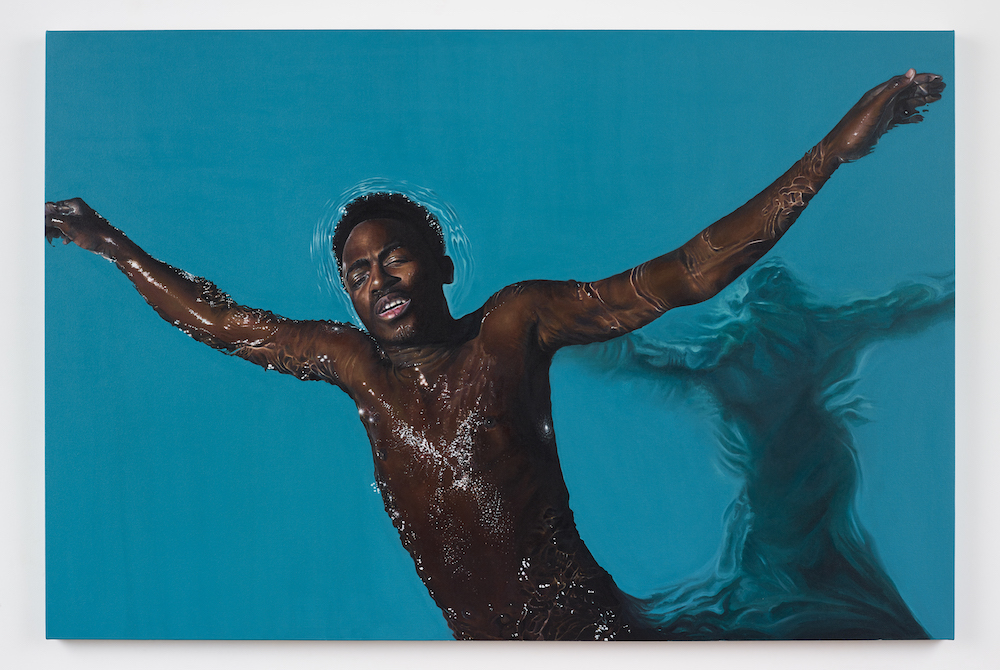

Your work radiates peace in many ways, but there’s more to unpack, like your tributes to victims of police violence, including Stephon Clark.

When Stephon Clark happened, my nephew was coming to visit. I picked him up at the airport, and as he approached me, I thought, man, if he was in his backyard on the phone, he could get shot. It was his dark skin, and he looked like a grown man because I hadn’t seen him in a while, and it made me think of the adultification of the black body and how that happens all the time, where people would look at a young black boy and think he’s a man, and treat him as such, or a young black girl who is treated older.

I took my nephew swimming so I could take photos and paint him, because he could be Stephon Clark. He doesn’t swim as often as me, so he wasn’t as comfortable, and he was kind of frowning in the sunlight, and I told him to stretch out his arms because I wanted to imagine Stephon back in the sun, or possibly scarified. I was fascinated by how many times Stephon Clark was shot, seven times. The police officers couldn’t look at that young man in the backyard and see potential for anything. They just saw a black body in a neighborhood, and thought, “Get him.” He fit the profile. So I looked at the autopsy report and I put galaxies where the bullets hit him, because there are unknown, untapped universes inside all of us.

When you study space and science, there are a lot of unknowns about theories, and there’s so much we don’t know, and science keeps changing and evolving because we’re learning, and I think of that as untapped potential, symbolically, and I think that’s in all of us.

Tell me more about the hidden imagery in the work, like the galaxies and maps.

Some paintings have it, and some don’t. In Reflecting my Sovereignty, at the heels of the girl, I put a map of Hazleton, PA and Coral Springs, FL. Hazleton is above the heel, and Coral Springs is above the foot. I kept looking at this young girl, and how beautiful she is, radiating this power, grace and beauty, and thinking again about how someone wouldn’t be able to see that without this large painting of her. In Hazleton, PA, there was a viral video of a security guard stopping a fight, and he grabbed one of the girls by her ponytail and smashed her face against a cafeteria table. In another video from Coral Springs, this police officer arrested a 14-year-old girl and started punching her in the ribs and beating her up. I’m assuming the cop didn’t know her age or have any respect for her, because why would you do that? She was in handcuffs, a young girl, she wasn’t going to get away, so I don’t know what’s going on in the cop’s mind.

When I saw that, I thought, what do you do with this information? Unfortunately, with this girl’s skin, the figure in the painting—it could happen to her. She talks back to a police officer, like Sandra Bland—you could just talk back or do anything, and this could happen.

So I put those locations in the painting, in the body, because I was thinking of Claudia Rankine’s quotes about how the body has memory. It’s part of something that’s happened physically within our culture. It’s small and subtle, and not the center of the painting, and the reason it’s okay for me if someone doesn’t see it or know about it, is because this might have happened, but it’s not the whole story of the person. Everyone has something terrible that may have happened to them, and once you tell that story, it’s sometimes all people can see. It becomes your epithet in their head, and I don’t want that. I wanted to put that in there because it happened, but I didn’t want it to be the epithet of this painting. She’s radiating sovereignty, she is glorious. These things happened, but it’s not her full existence; she is so much more.

This is how painting can open perspectives.

It’s therapeutic for me, and I hope it can lead to conversations. The adultification of black females, in particular, is scary for me, especially as I’m raising girls; hence why my daughter became part of the painting. I’m looking at her, she’s about to be 15, thinking about how she’s going to be treated on the street, and I recognize that she may have to face some of these things.

When I painted her in Reflecting my Grace, I put this reflection of light up and down her arm, and it became a camouflage, like an animal print, and I was thinking, with her light skin privilege, a young black girl as light as she is most likely wouldn’t be treated like the young lady in Radiating my Sovereignty because of her skin. But what comes with that light skin is the constant questioning of her identity from inside and outside the culture. “You don’t have this experience, so therefore, are you really black?” Our culture is sometimes defined through a lens of victimization and it shouldn’t be. You’re not more black because the cops see you a certain way, or you get followed in the store. These experiences that are sometimes associated with blackness are stereotypes, a box we create to define race, which is dangerous. It’s limiting, because obviously black people can be anything. We are everything. And with stereotyping, the skin is another layer to it.

I understand and identify with that, and I made that painting, Reflecting my Grace, because my daughter reflects me and my experience. It may not necessarily be all my daughter’s experience, but it was definitely mine. I was in private school, and people would say things to me, like, “You know, you really don’t have to call yourself black if you don’t want to.” Even the audacity of that mindset is so layered. And how do you handle that type of conversation, especially when you’re young?

You wrote the children’s book, Same Difference, about cousins with different skin tones, which I assume was about you and your cousin.

Yep, it was. I wrote it for my daughters when they were younger, and yes, it was in honor of my cousin. She was an editor and a writer, and she helped me with it. That’s how I knew Ta-Nehisi, because they were friends and journalism majors together at Howard University.

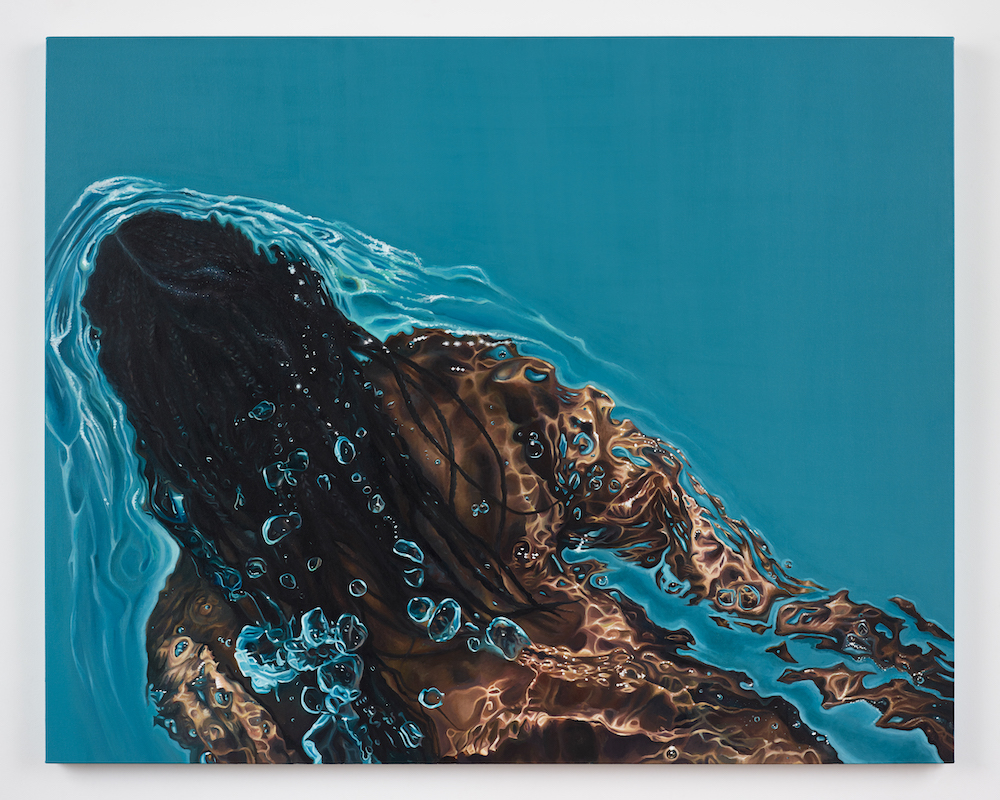

Tell me about your photoshoots for source material. Do you really shoot the images with your phone?

Yes, my iPhone with a waterproof case, and my two oldest daughters. They are my staff and my team, and they are totally underpaid. They only get food and shelter [laughs].

I usually start with a basic idea or image in my head, so we try that first, and then just go with the flow. It’s very improvisational, and I take 400 or 500 photos of the person doing different things in the water. One of my daughters is the water machine, making waves when I want, so she’ll be pushing the water, looking at me, rolling her eyes. If I need the person to come closer to the surface, someone else might hold the person’s body up a little bit. Someone takes the photos, someone makes the waves, and the three of us are a team in that way.

I look at the photos back in the studio, and I might like the hand in one, and the arm from another, so I mix them up in certain ways before it becomes one whole painting.

I know you get a lot of inspiration from literature, but is there an artwork that was influential on you?

I would have to say Winslow Homer’s The Gulf Stream. My dad had a print of it in his living room. He would catch me looking at it and say, “He’s gonna make it. He can see land, you just can’t see it. That’s a positive painting.” There are sharks around a man on a raft, with blood at his feet, and it looks like there’s a slave ship in the background and a storm in the corner, but the man looks cool, he’s just looking off to the side, even though the water is so turbulent. It’s funny, now that I found peace in the water, and I think about that guy’s expression. No panic. That painting influenced me subconsciously.

Everyone needs to look up this Homer painting to see the connection. Were the paintings in your recent show your largest ever? They’re so immersive at this scale.

I’m good friends with Amy Sherald, and I was starting with 4 x 5’ canvases I had already sketched out, and she said, “No, no, Calida, you gotta go bigger. Just do it. You’ll love it.” It kind of stole my thunder for the day but I’m so happy it did! She’s a great friend, and I can take criticism. Sometimes I don’t like it, but I’ll do it [laughs]. I’m happy she encouraged me to do that, and now I want to go real big all the time, even bigger.

I love that story! Let’s talk more about water and its metaphors that resonate with you most.

Water is definitely a spiritual healing element for me. I’m fascinated with how I feel in the water, how the light glistens off the water and looks magical. The fact that we’re made up of water, that we can’t live without it, and then the culturally historical concept of water with black people. I remember visiting family on the Eastern shore of Maryland where my father would take us to the beach, but some of my family wouldn’t go in, because they remembered when they couldn’t go to the beach during segregation. A lot of people didn’t go to the beach there, even though it was a mile from their house. It was their personal protest. That stuck with me, that my Uncle Henry would never go to the beach with us.

And thinking about access to water, or segregation of water, and the fact that 60% of black people don’t know how to swim because of that, but then black children are the highest percentage of drowning victims.

I also started reading water memory theory, which is the basis of homeopathic remedies. Whatever you put in the top of the stream comes out at the bottom with the remnants of what went through it. That made me think of the ocean, and The Middle Passage, and how many bodies were thrown off the slave ships, and how there’s memory of a culture in the water.

I think there’s this soul of the water for me, of memory, space and time, all of it colliding, the molecules… for a galaxy to be in the water makes sense to me, since we’re all made up of stardust, let’s say, it’s all there, and then when I’m splashing in the water, and light hits it, it sometimes looks like stars. It just glows. I’m even fascinated by how my body looks and feels different in another element.

Either weightless or sinking, water is supportive—or it can be the opposite.

It’s so scary. You’ve got to let go. When I started swimming, I had to let go of my fears, and I realized I float better if I put my head further underwater, which is against my natural instinct. But it’s about trusting myself and relaxing in the water because the more tense you get, the more you sink. And that idea became a metaphor for me and life, thinking about how I can’t control all that’s happening right now, but there’s nothing I can do but let go and relax, and try to find the beauty in it. That’s the only thing I can do in any circumstance, and that’s the only thing I can do in the water. It was through the discovery of myself that all of the art came from. I feel like I’m just beginning. I have so many paintings to make with water, because I haven’t gotten into dark night water, or water at sunset when it’s shimmering. I haven’t gotten to the ocean, or all the different colors… it’s just one painting at a time. I’m still discovering as I paint, which makes it more fun, like I’m still learning and thinking about the subject matter, and the beauty of water, and how I feel in water. I’m going to get lost in the water, and I can’t wait.

See more of Calida's work at @calidagarciarawles and vsf.la

Buy the Summer 2020 issue here.