Upon entering a museum into a museum, we are immediately thrown into a time warp. History surrounds, engulfing your sense of place and era, catapulting into contemplation, a dreamy assessment of how, where and why works were made. Often, as is the case with the brilliantly dense Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott, presented at the New Museum in NYC, we find ourselves asking how was this missed, why did it take so long for art history to catch up and capture the essence and depth of a career of such a pivotal figure like Colescott. Race matters, yes, and our institutions are finally asking these questions: why did we fail to recognize the complexity of such a career and fail to enter it into our art archives? How do we present such a life’s work with reverence while presenting it as a historical hall of mirrors for self reflection.

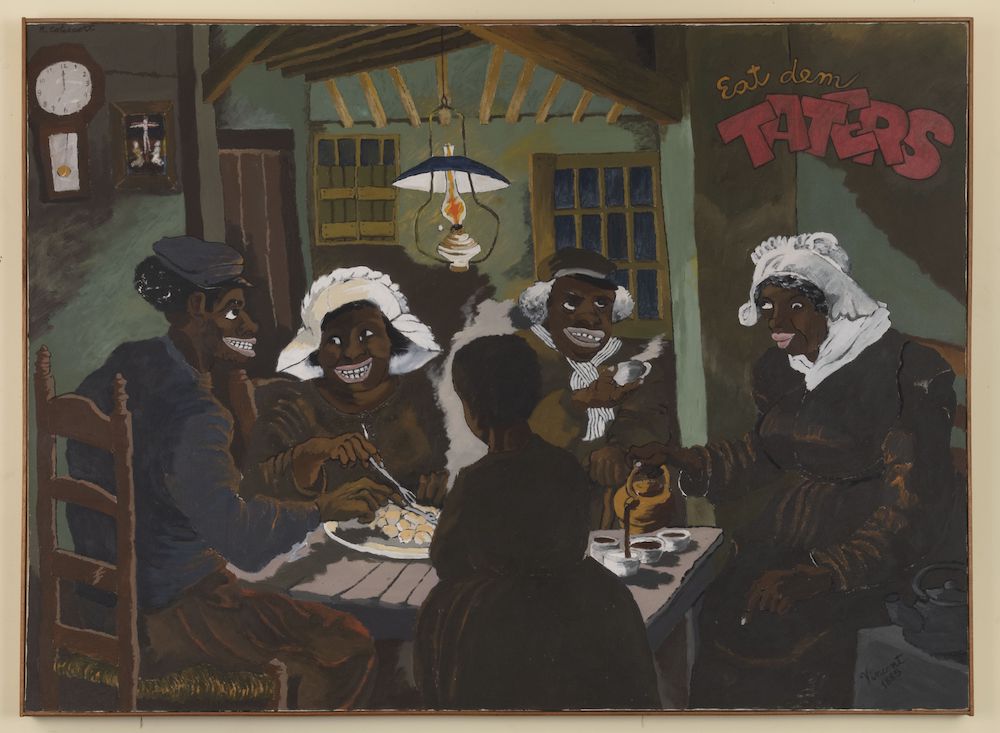

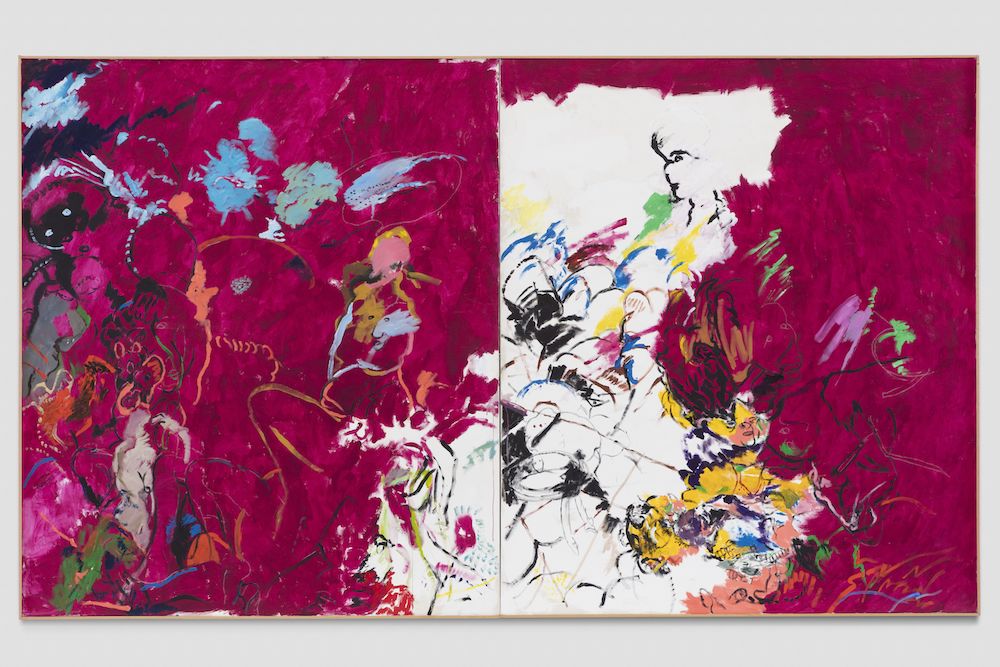

Because Colescott was doing this in his time. He was placing Black figures into our most American of paintings and historical moments, creating his own conversations about what the art world had, indeed, missed and continued to forget. His often satirical works challenged how we looked at our visual language, but was he remaking history so much as telling it how it is and was? And that is the overwhelming feeling you have when you walk into this presentation; we are thrust into history to confront what we haven’t considered or was omitted. That Colescott was actively placing Black bodies onto the famed George Washington Crossing Delaware River 1851, or de Kooning and Lichtenstein's, he’s constantly playing with the idea of two historical American narratives. This sort of boldness led the way for the likes of Kehinde Wiley to paint Black bodies into the mold of European Masters. Even Colescott's crude and boldly humorous works could be seen in the likes of Peter Saul and Robert Williams. He used appropriation to appropriately tell the audience that history is uncomfortable. He used what we know to show us what was left out.

Colescott passed away in 2009, but it was this observation he made in the early 2000s that was a premonition of what was to come in the art world. “At this particular time people would like to feel a kind of intimacy in art. The move from the ideal and the classical, the need to feel and understand things and to identify things in the painting from their own lives—trivia, violence, confusion—is an element that has been unaddressed for a long time in art. People today are concerned with it. There’s a distrust for art that doesn’t concern itself with it and a real appreciation for art that does.” What is so compelling about this particular exhibition, and this amazing and revelatory painter, is that if we are to look into our history books and begin to address all the narratives that make us who we are, we should feel overwhelmed and determined to allow for history to be malleable. Clevelry, the New Museum simultaneously showed the works of Brazilian video artists, Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca on a floor above Colescott. One work in particular placed the viewer in the center of a theater with two screens showcasing a Brazilian dance troupe, with an inability to see both screens at the same time while two vantage points of the same moment surrounded you. You were enveloped by two narratives going at the exact same instant. What we are left with is that, even in our best efforts, there are always new perspectives to be seen, to be enriched by, to give us all new meanings and understandings of how stories work. This is what good art, and what a good museum, should be doing. —Evan Pricco

Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott is on view at New Museum through October 9, 2022