Dallas-based artist Rachel Strum and the Brooklyn-based artist duo CHIAOZZA may have never met before their joint exhibition Cosmic Bloom at Hashimoto Contemporary San Francisco, but both have a clear commitment to artistic experimentation. This is evident in the art they make—their use of unconventional art materials and inventive use of conventional ones reveal a dedication to exploration, to play, to asking “Well, what if?” Together, their paintings, sculptures, collages, and works in between create unexpected and thought-provoking representations of the world around us.

Before their joint exhibition opened, CHIAOZZA (Terri Chiao and Adam Frezza) and Rachel Strum spoke with Hashimoto Contemporary’s Katherine Hamilton about their practices and how they try to stay innovative, the questions of the universe they want to explore, and how they situation their practices within the world.

Katherine Hamilton: I want to start by talking about worldbuilding. It seems like there’s a world building element to both of your practices—for CHIAOZZA quite literally, in the large scale, otherworldly installations you often create, and for Rachel in the re-imagining of the elemental aspects of the universe around us. Can you speak to this element of world building? Where do you think it comes from, and where do you hope it will lead you?

Terri Chiao (TC): World-building has always been present in my life ever since I was a child immersing myself in picture books, drawings, furniture-arranging, and creative play outdoors.

In some ways, world-building is an empowerment tool. It’s an invitation to help shape the world around us in positive ways that we can understand and reach, without having to rely on what others think we should do. This approach slides into our practice, as we love to create worlds that can hopefully help expand the universe of possibilities little by little.

Adam Frezza (AF): World-building comes from a response to what’s already there. For me, it’s about recognizing my opportunity to help augment, shift, and hopefully enjoy the spaces around me. I think of it like preparing myself for the work of living. If my space and objects and the things around me feel like they’ve found a way to fit into my life, then I’m more prepared to operate and access my creativity.

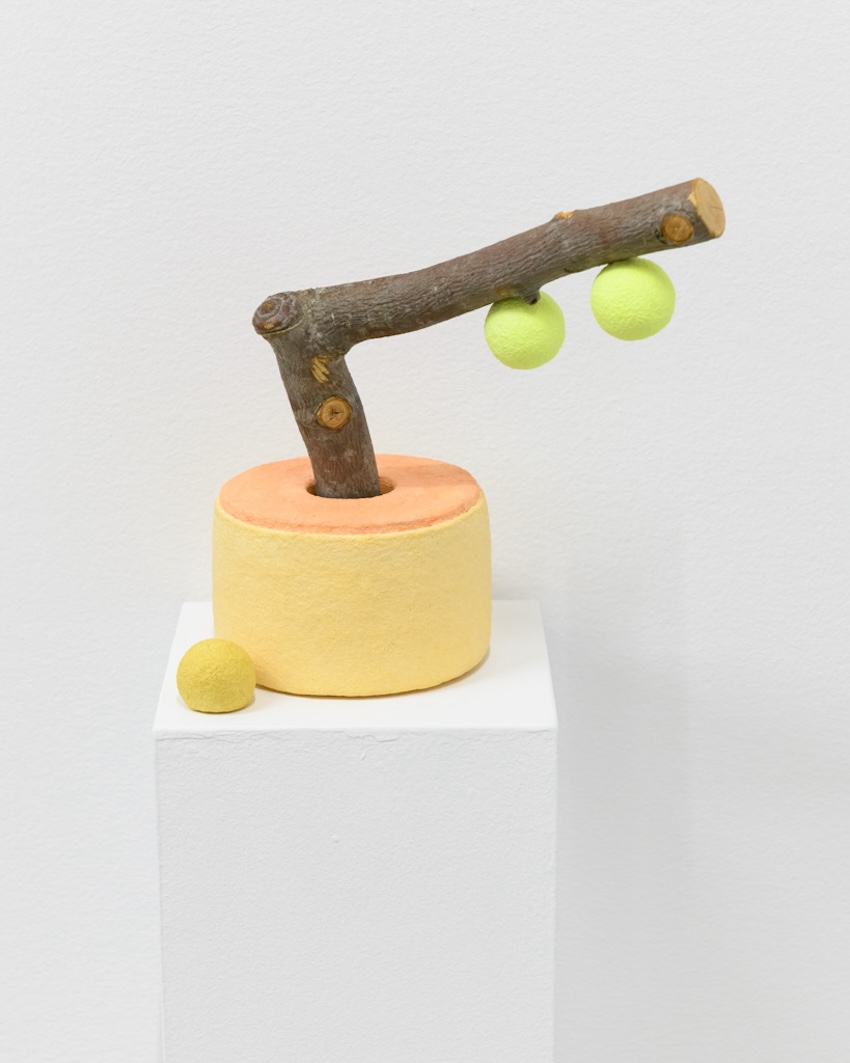

Rachel Strum (RS): My intention is to create imaginative spaces. The sculptures I made are like objects that can be discovered within the imaginative worlds of the paintings, almost like artifacts. I'm not totally sure where this impulse comes from, but I've always been drawn to it. As a kid, I always loved dollhouses and miniatures. Maybe it’s the opportunity to create different outcomes within the same boundaries or parameters. The multiverse, but make it miniature, more accessible and easier to manipulate.

CHIAOZZA, you often transform things that are recognizable into something unknown, as though you are making representations of a thing drawn from the mind of someone who’s never seen it before. Have you both always been interested in reframing everyday objects?

TC: We like to question the things we think we know, such as the shape and color of a flower or a rock or a tree, by looking at things closely, shifting our perspective, breaking down what we see, observing how they feel, and representing these concepts in different forms, materials, colors, and mediums. Reframing how we see and understand things is a way to keep our minds elastic and open to new ideas, transformation, different viewpoints, and, hopefully, progress.

The practice of shifting scale and shifting perspective is something I’ve done since I was a child. For instance, when playing outside, it’s fun to pick up an acorn and imagine it as the centerpiece of a hearty feast for a gathering of tiny creatures, that the acorn cap is a salad bowl or a hat or a goblet, and that the tree the acorn fell from is an entire neighborhood or civilization. And in a sense, it is.

AF: I’ve always found value and fascination in trying to loosen knowledge of what a thing is and reconsidering what it can be. One of Terri’s and my favorite pastimes is walking into any hardware store and looking at the shapes and colors and materials of a thing first before ever considering its function. From those points of discovery, we might find inspiration to create new shapes, colors, and textures.

Rachel, you have a background in installation and sculpture. How did your practice in those mediums inform your current body of paintings?

RS: I tend to gravitate towards more tactile, dimensional, or experiential approaches when it comes to work. While I do have a deep appreciation for traditional paintings, my personal art practice has always been driven by experimentation, interaction, and the use of different materials. Most artists seem to start in childhood with a love of drawing, but I always wanted to create messes with materials like paper mache, clay, and mud. My earliest memories of art involve building paper mache mobiles and being obsessed with making dioramas for school projects. I actually started painting mostly to teach myself how to paint.

It makes a lot of sense that your practice began in your childhood, as it seems you’re often trusting your gut while making it. Can you describe any experimental practices you implement in the studio to find new ways to create?

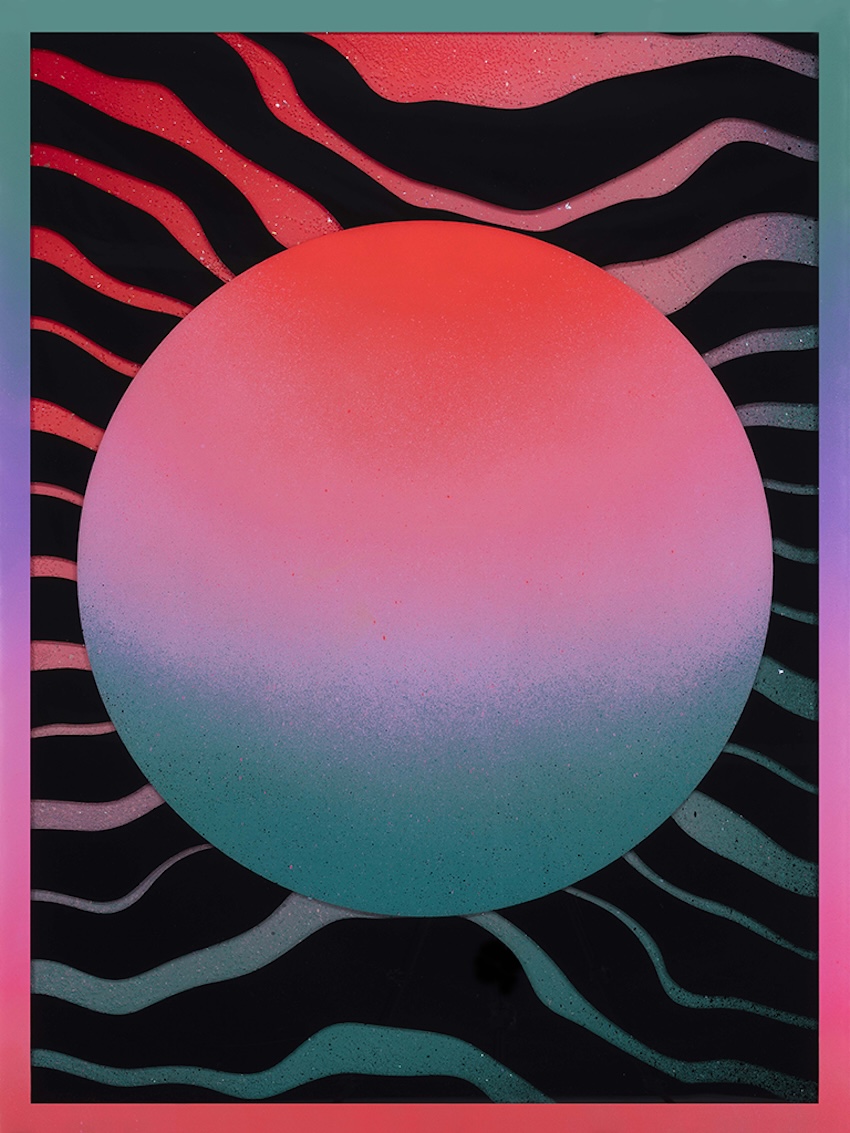

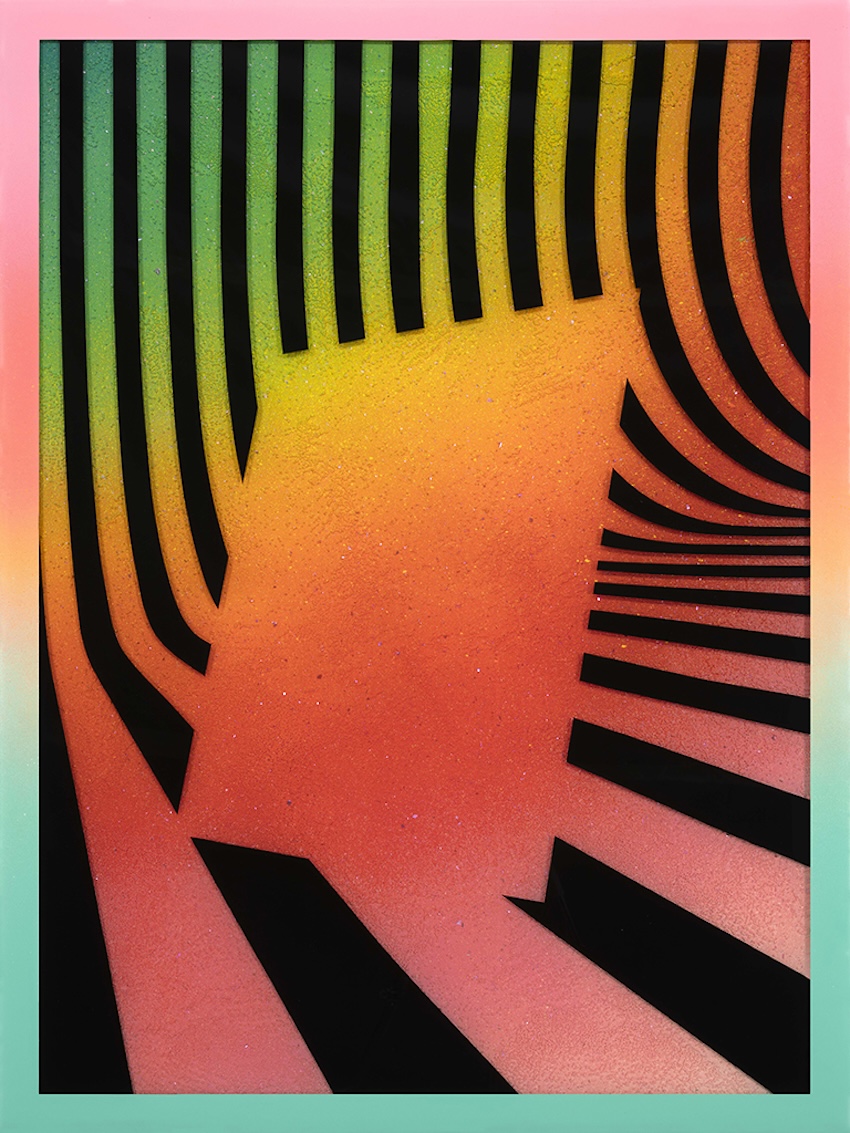

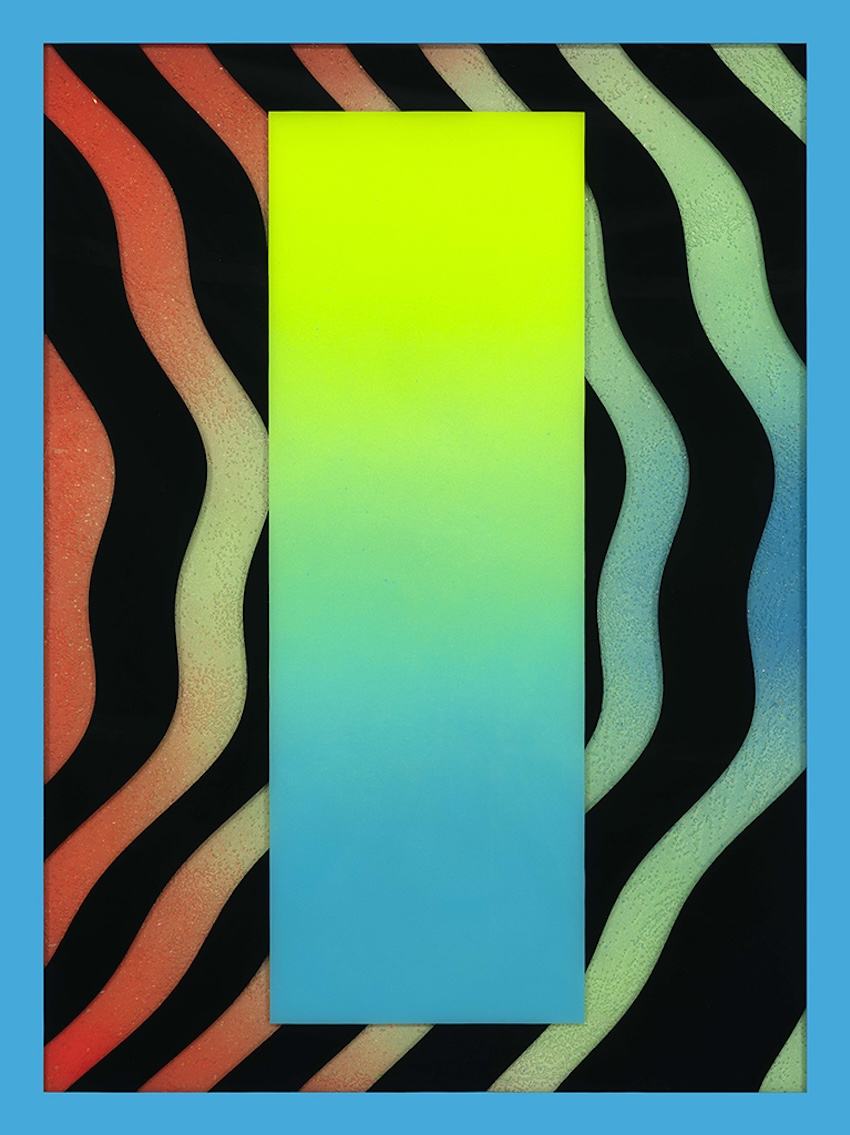

RS: I always start by digitally rendering the composition, textures, and color palette. Since the process involves layering of resin to create depth, I need to plan and reverse engineer the painting before even beginning to paint on the panel. If I paint an element out of place in the layering timeline, the entire painting takes a different direction. It’s difficult to backtrack or rebuild with resin, and it takes a lot of time, so I begin with a plan, but the work really builds itself in many ways. The translation from digital to physical is where the challenges begin, and much of how I act and respond is intuitive. I experiment with various techniques within each medium, and I have built up several practices within my visual lexicon that allow me to have backup plans when I encounter difficulties in achieving what I originally set out to accomplish. When I find myself stuck, I dive into my lexicon of techniques and try something different.

Terri and Adam, optimism seems to buzz around CHIAOZZA’s artistic practice. Do you center optimism in your making?

AF: I can’t help it. It almost feels like a rebellious act to remain optimistic. We also recognize that joy and sorrow are inextricably linked, and we aren’t afraid of a healthy dose of melancholy within our optimism.

TC: Yes, we value optimism in our making. While I don’t think of us as blindly optimistic, we value the ability to hold an awareness of possibilities, both positive and negative, and we try to move forward with positivity. To me, optimism feels better to share with the world, and it also makes for a more enjoyable day to day existence.

You mentioned that for this show, there’s a heightened awareness between the making or experiencing of something that is “artificial” and something that is “natural.” Can you pinpoint what sparked this interest for you? Or is it something that has grown over time?

TC: The line between natural and artificial is a construct, because in some ways everything is natural: it’s here, it exists, and we exist within it. At the same time, everything is artificial, because humans have impacted the earth so much that even what we think of as “nature” is heavily influenced by the presence and alterations of humans.

When we speak about “natural” in our practice, we are referring to raw materials, like wood from a tree, or even materials that can be directly traced to their sources, such as manufactured wood products, paper and paper pulp from trees and plants, and even raw linen, which comes from plant cellulose. Much of our inspiration comes from experiences with the natural world, such as hiking through a surreal landscape, collecting stones and seed pods, appreciating the sunrise or sunset, taking a moment to observe the vibrant mossy underbelly of the forest floor, and more. At the same time, we also find great inspiration in exploring the urban natural world of New York City and its unexpected, delightful discoveries, such as flowers popping up through sidewalk cracks, well-organized pipes on the side of a building, trees growing inside abandoned structures, nature and architecture co-mingling to create an urban jungle of curiosity and confluence.

Our hope with creating nature-inspired work is not to suggest an alternate reality; rather, this may be one way to process our experiences and transform our observations and inspirations into new forms that will hopefully contribute to the cycle of wonder, appreciation, and perhaps new perspectives.

Rachel, you have quite an electric color palette that some might refer to as “unnatural.” Where does this come from?

RS: I have always been fascinated by color and color theory. It's a fundamental element of the visual language that can be relatable or deeply personal. Although figurative work dominates the contemporary art world, I believe that color is the connective tissue that allows people to connect with my mostly abstract work. Working with bright and electric color palettes has been a fun challenge for me. The intensity of colors either magnetically draws you in, or repulsively turns you away, so I strive to find a balance within the intensity.

Is the glitter aspect a new element of your work?

RS: I have been experimenting with different pigments and glitter in my paintings for a few years now. It all started with a playful attempt to bring more dimension into my paintings and explore how ambient light would affect the surface of the work.

I think it’s really effective! Especially how the glitter catches light and seems to release it as you move and walk around the pieces.

CHIAOZZA, for this show, you’ve also been working through experimentation, especially in the Exquisite Plant Collages. While this might be the most conspicuous reference to games and play in the exhibition, I’m wondering what other types of play you’ve implemented into your practice?

TC: When Adam and I first met, we played a lot of collaborative games as a way to get to know each other. We continue to play and enjoy collaborative games. Many of these games don’t involve special materials, just a pen and paper or objects we have lying around. Exquisite Corpse, for example, continues to be a popular game, especially with our daughter Tove who has also enjoyed playing with us since she was four. We also play collage games, taking turns making “moves,” and shifting the composition around, adding shapes, etc., and sculpture games, such as taking turns stacking miscellaneous objects one at a time to create a compelling form. Sometimes we even play navigational games, where we will go on a walk and at each intersection, we take turns deciding which way to turn and walk next, which can lead to unexpected discoveries and experiences.

Ah like the Situationist International Dérive! How have these forms of play affected your collaboration?

TC: Over the years, a collaborative language (both linguistic and visual) has emerged from these games and folded itself into our creative approach, which is often a very back-and-forth dialogue-based process. Some collaborative games lead directly to new series of artworks, such as our “Meander” series, which has taken the premise of the squiggle drawing games into collage and sculptural formats.

AF: The practice of saying “yes” to explore experiments and test ideas allows us more room to grow and discover something we may not have had we said “no.”

I also want to talk about the bodily elements of your work. Beyond the “corpus” aspect of the plant collages, you also incorporate found tree limbs and branches into this series of sculptures. I know I’m being a bit vague, but I’m wondering if you can unpack the relationship between body, space, and imagination here, as you're transforming the actual object referenced in the artwork rather than creating new or different mediums to represent this tree.

TC: The relationship between body, space, mind, and imagination is, in some ways, all we know to be true, because we can sense all of these things immediately without having to analyze or think about them. To value this rudimentary and essential space of truth and feeling is one of the most important things we can do as world citizens. Keeping in touch with our connection to self, environment, and the imagination strengthens our shared world and our engagement with it.

On a more physical level, we value our sensory experiences in the world, such as being washed over by waves of intense colors of sunset, the way a sun-warmed rock feels when held in the hand, the way geographical formations smoothed by water erosion can surprise and compel us, the way a log fallen in just the right place invites our bodies to walk carefully across it, or how one can see a tiny world in a bed of mosses just by looking closely. These kinds of experiences inform our work on many levels, from the colors, forms, materials, scale, and compositions used in our projects, as well as how we hope viewers will interact with the pieces.

The new paper pulp paintings also incorporate a different approach from previous pulp paintings. Namely, they are made with pigmented pulp, rather than paper pulp that has been painted. The pigment is pre-mixed into the pulp, and each color is a different batch of pigmented pulp applied at different times or onto different pieces of material that are then assembled. The integration of the color directly into the material gives a different kind of luminosity and texture, so that what we are actually perceiving is the soft, rough surface of paper pulp itself. We love the natural and curious feeling this gives the work—it’s both pleasing and uncertain at the same time.

AF: I think a lot about gestures and the subtle variation and differences of all things in nature, offering so many different forms of expression. If we can relate those things back to a body, then almost everything has emotion through its gesture.

Rachel, I know for this body of work you mentioned an interest in depth—the possibility of filling or emptying space. I think you have, for a long time, focused on the invisible laws of the cosmos, but these themes seem to flow through the works in Cosmic Bloom especially. Were there any recent incidents that prompted you to consider these questions of the universe more deeply?

RS: It was something that naturally evolved both within my work and within myself. For me, art is a way to visually represent the inner dialogue that goes on within all of us. When I visualize the depths of the human brain, I see a galaxy, and this image has become a powerful symbol for me. The death of my father, which happened when I was in college, was a profound experience that has shaped my perception of the universe and our connection to it. Through my art, I have moved beyond more conventional ways of representing spirituality and found comfort in thinking, relating, and expressing myself in a more cosmic way. Although this was mostly a subconscious decision, it's something that I am now beginning to form and process through the work itself.

We called the show Cosmic Bloom because both of your works speak to this potential relationship between the earth and the stars—to me, it reflects an optimistic, speculative symbiosis, or at the very least ripples, cause and effect. What types of ripples do you imagine your artworks to have?

RS: Personally, I seek work that presents me with challenges and questions about the process. I want to know why I'm doing things a certain way and whether there's a better approach. I also want to experiment with different materials to see if they achieve a particular feel or end result. Every body of work should offer something new that I can build on going forward.

TC: We try to create work that we want to see in the world. The hope is that if we create and share things that feel natural, honest, and beautiful to us, perhaps someone will see it that way, too. And perhaps that will encourage others to share what feels natural, honest, and beautiful to them with the world.

AF: I think it’s hard to know how and where the ripples will go, and our job is to keep making sure we’re throwing our favorite stones in the fountain.

Cosmic Bloom is on view at Hashimoto Contemporary San Francisco through February 24th. Installation images were taken by Shaun Roberts and opening night reception photos were taken by Kuan Ya Wu.