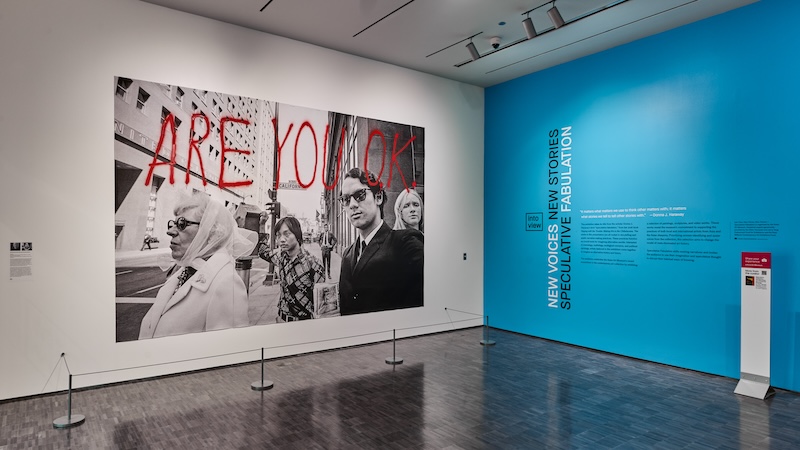

Into View: New Voices, New Stories is a new exhibition on view at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco and features 14 primarily women-identifying and queer Asian American and Asian diaspora artists that are taking grasp of the old and shaking it new. Specifically, these artists take on the roles of storytellers and historians, looking at the narratives that we have been told about our lives and histories, and altering them in ways that disrupt and challenge our traditional ways of thinking. The process of doing so is called “speculative fabulation,” inspired and pulled from author and professor Donna Haraway, as a touchstone for the entire exhibition. The results of such a strategy are paintings, sculptures, and video works that conceive of not just new realities, but new worlds. I’m always interested in a world reimagined. It keeps me hopeful, and wishful for the day when the daydreams and fantastical possibilities can become our reality. If there is a God out there, I think she’d agree that the sincerest form of flattery is imitation. And Into View demonstrates that the universe is big enough for every world we have yet to imagine.

I spoke with the exhibition’s curator, Naz Cuguoglu, Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art & Programs at the Asian Art Museum for more insight into what's on view and how these works challenge the institution.

Shaquille Heath: I love the term speculative fabulation, and everything that comes with its meaning. Can you tell me how you first became introduced to it, and when you knew it would influence a future exhibition?

Naz Cuguoglu: I came across theorist Donna Haraway’s term “speculative fabulation” when I was organizing my thinking around art and artistic production for my graduate exhibition at CCA (California College of the Arts.) We curated a show for the Wattis Institute as a curatorial collective of four and we were just blown away by the open-endedness of her formula and its critique of cultural practices. “Speculative Fabulation” can mean so many different things, and it’s supposed to. It was even the working title for this current exhibition, Into View: New Voices, New Stories, since the focus is on artists taking something old and imagining it anew, like taking an old technique but making it so contemporary that it feels like a completely new approach.

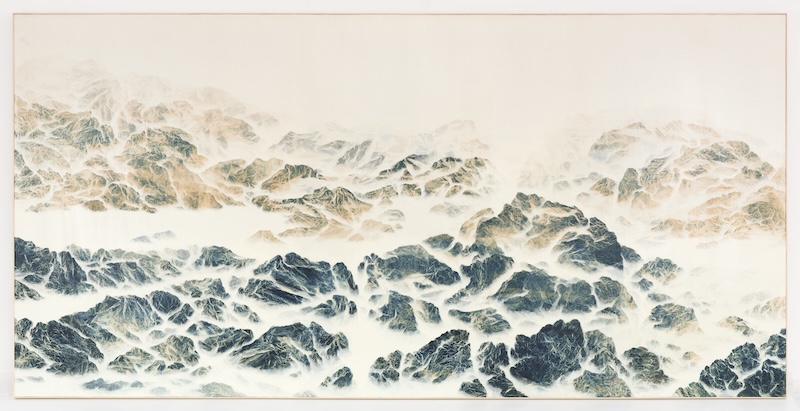

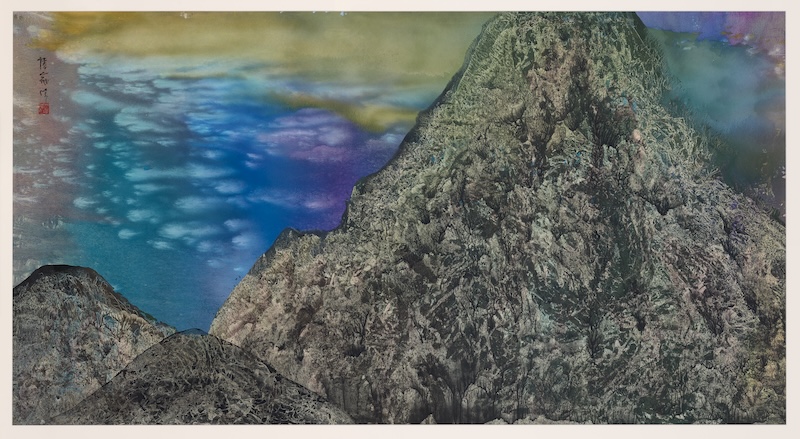

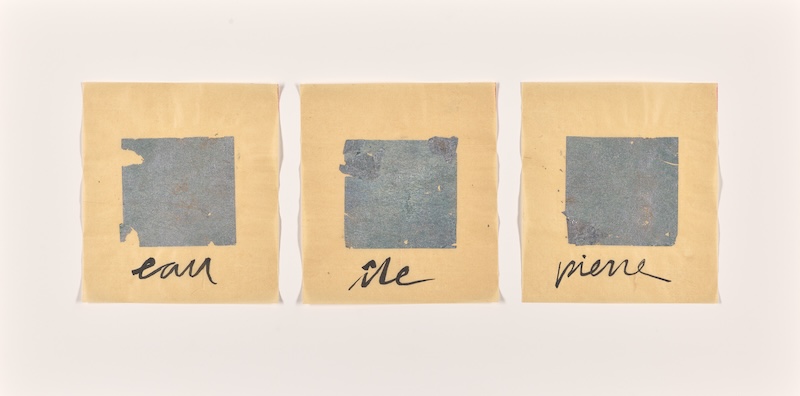

Look at Wu Chi-Tsung’s Cyano Collage that starts from within a Chinese landscape tradition, but enlarges it through photosensitive means, exploding the past by making it thoroughly modern, blending East and West into a fantastic landscape, a space that only existed in his mind, but which we can now project our own selves into. It’s also a thought-provoking artwork, which I believe is important, because we have to remind our audiences that contemporary art is still on a continuum with a variety of art histories and it’s our role as contemporary curators to challenge both assumptions of audiences and museum structures.

I became really invested in challenging museum structures through artistic narratives two years ago as a fellow at the museum’s Practice Institute, which is our residency program for research into the future of museums. My research as a fellow was to surface stories of primarily women and queer artists that were already in the collection, but which we hadn’t yet shared. These stories were about imagining alternatives, imagining the kind of fables these artists would have wanted to have heard as children, maybe to guide the lives they lead today, but which they now create through their art rather than receive through tradition alone.

Museum collection shows often get a bad rap, but they are a big indicator of what a museum’s values are. Talk to me about Into View: New Voices, New Stories and how this exhibition came into fruition.

I love this question! What’s really here is about giving voice to Asian AND Asian American artists. The contemporary collection started really being built up by Abby Chen, our head of contemporary art, who pushed hard for changing who we collected. Before her, Asian American artists, which would also have included diasporic artists, were not accepted as being “Asian” enough to be acquired. We have completely flipped that script and now we aim primarily to give voice and give space to underrepresented artists who are not heard from as much, especially women and queer artists and those with a local connection. And this exhibition is about showing not only the diversity of Asian American, Asian, and Asian diaspora art, but the points of thematic overlap — because these artists are interested in making change.

You know it turns back to the “speculative” piece, since speculative fiction is a cover word for sci-fi, which is starting to shed its pulpy reputation and be embraced in the mainstream as a source of “legitimate” cultural inspiration. I think about the great writer Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower: “All that you touch / You Change. / All that you Change / Changes you. / The only lasting truth / Is Change. / God Is Change.” Right now, this museum values change.

It’s probably surprising to most people that the Asian Art Museum has only been collecting contemporary rigorously over the past 5 years. Why was it important to you to switch this up? What are the special works that visitors can see on view in the exhibition?

I want to give credit to our director Jay Xu for transforming this museum and building a pavilion that freed up multiple galleries to present contemporary art. It was challenging before because we didn’t have the space to always have it on view, and so it wasn’t as big a priority, but for me, it’s incredibly important to showcase artists in their lifetime. The art world loves an artist who was overlooked in their time, and they love to look back and feel like they discovered something, but my goal is to become an institution that does this work during the artist’s lifetime. Don’t get me wrong, it’s vital to do that research and recover those stories — history is always a choice, right?

Look at Cathy Lu’s ceramic sculpture Nuwa’s Hands, which starts with a Chinese mythological goddess, Nuwa, who repairs broken skies and creates humanity. But Cathy tells us she was thinking about contemporary goddesses, and saw them in the immigrant women who work in nail salons, repairing and renewing other women’s lives. In the sculpture you see these powerful, almost monstrous hands of these women, with curling nails, and we hear directly from the artist about the racialized role nail salons play in the United States. We don’t have to look back and try to figure it out, with the artist as our guide we can see its relation to our own experiences today.

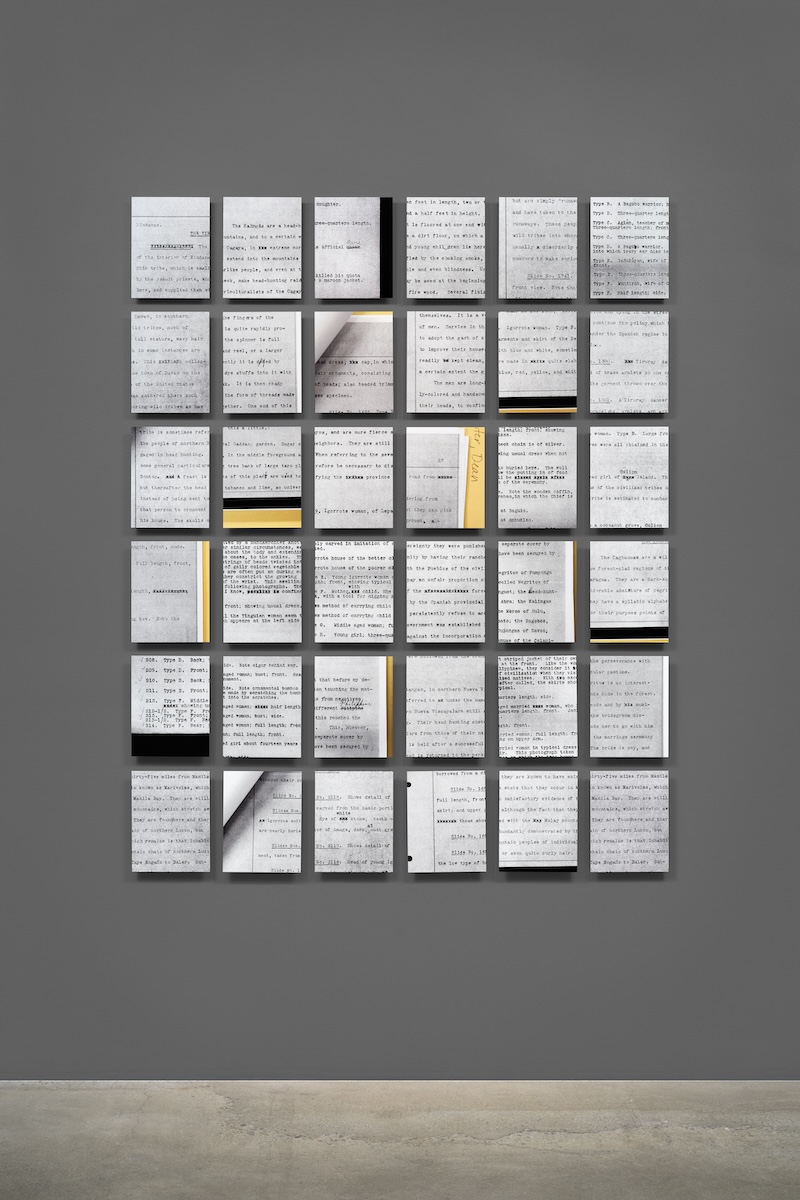

I also love TT Takemoto’s video work, On The Line, which is based on the true story of a butch Japanese figure in prewar San Diego. This story is poetic, not a documentary but a manipulation of the archival material TT had, which they used to create a performance within the work. It’s humorous, but also poignant, since TT told us the film is thinking about agency, and who has access to history, who has the right to tell a story. TT is a fourth-generation Japanese American artist, and they have a legacy within that identity that they share with audiences in a really inspiring mix of personal and imagined storylines. The film “tricks” you into wondering what’s real, but with a wink so you know there’s no “wrong” answer.

Some of my favorite works in the exhibition are those inspired by folktales and mythological stories, often passed down across generations. It feels like a game of telephone (in a way) that changes a bit through every generation. What gap are these artists filling by taking on these themes?

Calling these reimagined mythologies a game of telephone is a great metaphor because it gets to the psychological dimension of those exchanges, where you subconsciously add or switch words and images to better reflect your own mind, your own experience. Looking at Younhee Chung Paik’s large oil on aluminum, Apollo in Love, we have a Korean woman who immigrated to the Bay Area taking an archetype inspired by a visit to a temple in Greece and reinvesting it with her own mythos. She poured the paint on a piece of metal cut into a shape that recalls the torso of a broken antique statue and just let it move how it wanted. She’s so interested in chance, in the power of the cosmos, of letting go of her own authority as an artist, of pushing the limits of materials and artistic agency, which is like an echo of what a myth is supposed to do, right?

Some artists are looking directly at old stories and making them new. Rupy C. Tut’s piece is the clearest example, taking what was an Indian love story between a man and a woman, but changing it so that a woman is now the focus, that she operates in a mythic space but in this version is empowered to chart a course through terror all on her own, so it becomes about self-love and women's empowerment. Rupy’s version fills a gap because there’s a need for new or updated myths that empower and liberate us.

Again, these are mostly all Asian American and diasporic artists, so they are not representative of their “nations” so to speak, and there can be freedom in that. But it’s also one reason we wanted to include their names in their “native” languages and scripts in the labels — not something we normally do — both to honor that cross-cultural moment, but also to show that little gestures in big institutions offer potent opportunities for change.

Into View: New Voices, New Stories is on view at the Asian Art Museum in San Francsico through October 17, 2024