The four carved granite faces of Mount Rushmore may claim status as the world’s largest, but other forms of sculpture carry their own weight, remarkable texture, subtle meaning and private statement. Wing Yau creates moonbeams from seedlets of pearls and drops of rainbow from the confetti of opals she carefully sources. Her jewelry sculptures reflect a connection to the people and country of provenance, to her team and finally, to those who choose her pieces from Wwake to create their own expression.

Gwynned Vitello: You almost made a 360, in starting art school to study sculpture and then shifting to making jewelry. What did the younger Wing Yau have in mind when enrolling at the Rhode Island School of Design?

Wing Yau: This question brings back waves of nostalgia! I graduated after studying sculpture at RISD and wanted to make art in my studio—but honestly had no direction. In school we learned to weld and cast metal to make larger scale sculptures and how to make video art with equipment from the school. After graduation, it was like a plug was pulled, no studio and the tools I needed to make what I’d made before. I knew how to work with my hands, so my work shrunk and I worked out of my bedroom with textiles, clay and wax. These sculptures became wearables, then became jewelry—which I hear has been a natural transition for a lot of sculptors! Studying sculpture gave me a full understanding of the soldering process and casting within jewelry, and ultimately to become a better designer and communicator. It’s not just magic—there’s a lot of practical problem solving in building sculpture, but I think it’s fun being both problem solver and artist!

How was life as an aspiring studio artist? Sculpture can be a commercial and arcane challenge, so I’d like to hear about your personal experience.

I hit a wall immediately in moving back home where I had no artist community. Yes, we should make work for ourselves, but so much of my motivation was engaging with others, and I lost that and my studio when I moved. My work had to change, and I had to be okay with that.

After finishing internships at NYC galleries, I ended up working as a barista, hoping to meet some “cool” artist types. Nerdy, I know, but I’d wear what I made in hopes of garnering “feedback”. Having just graduated, there was nothing to lose –– and this was my only audience! It was impactful on the work in realizing that the pieces should be smaller to be more precious, intimate and relatable. They retained an artistic element in texture and shape, but I was really invested in how familiar materials could spark inspiration and, ultimately, make a meaningful connection with others. The delicate gold jewelry, each piece like a little sculpture, opened doors for me.

Were there childhood and family memories that contributed to your themes and fascination with jewelry? Does this play into the name of your company?

The irony is that my parents showed no interest in jewelry! We have multiple generations of immigrants, which means lots of the heirlooms were left behind with their former lives, so there’s really no family precedent! Most inspirational was my mom’s fantasy of becoming an anthropologist, thus her passion for collecting masks, sculptures, weavings, and sand paintings from faraway places. When I was younger, jewelry was a small way to start my own collection. Hand carved wooden earrings and homemade necklaces woven from beads were an inexpensive way to remember where I’d been. The purchase would always be a simple, meaningful memory, and so, a meaningful collection.

I design to mimic this ease. To me, WWAKE is about gestures, exploring an idea over and over, not necessarily reinventing myself, but getting deeper with every layer. Each piece is a little thought that in combination reads as a poetic whole (a collection!) The name WWAKE is a metaphor, like a wake in the body of a water where little gestures create the whole. Also, it marked the end of my studio practice as it was (a wake) and so marked a new beginning (awakening). If it sounds cheesy, it felt appropriate. Maybe WWAKE is about hope and being ok with change.

What was the first piece that caught on and what materials? Were you surprised at the development?

My first project was called Closer, an investigation of trade materials––silk, cotton textile necklaces, bronze, silver, and bits of gold. I liked that these materials had a loose sense of history before I even manipulated them into sculpture. I was proud of that first collection, which had Sheila Hicks-inspired textile pieces, and metal bracelets that stacked and were literally embedded with my fingerprints, as well as little gold earrings and rings that captured simple shapes I made, all the materials soft and touched with respect for a tender, gestural collection. That said, stores came back and they were, like, people love the metal pieces because, well, they look like jewelry, not sculpture, but don’t feel comfortable buying gold rings that don’t have gemstones, feeling they lack “perceived” value. Getting that feedback was jarring, but it did make me think. I personally didn’t like wearing gemstones, so this was a real design challenge.

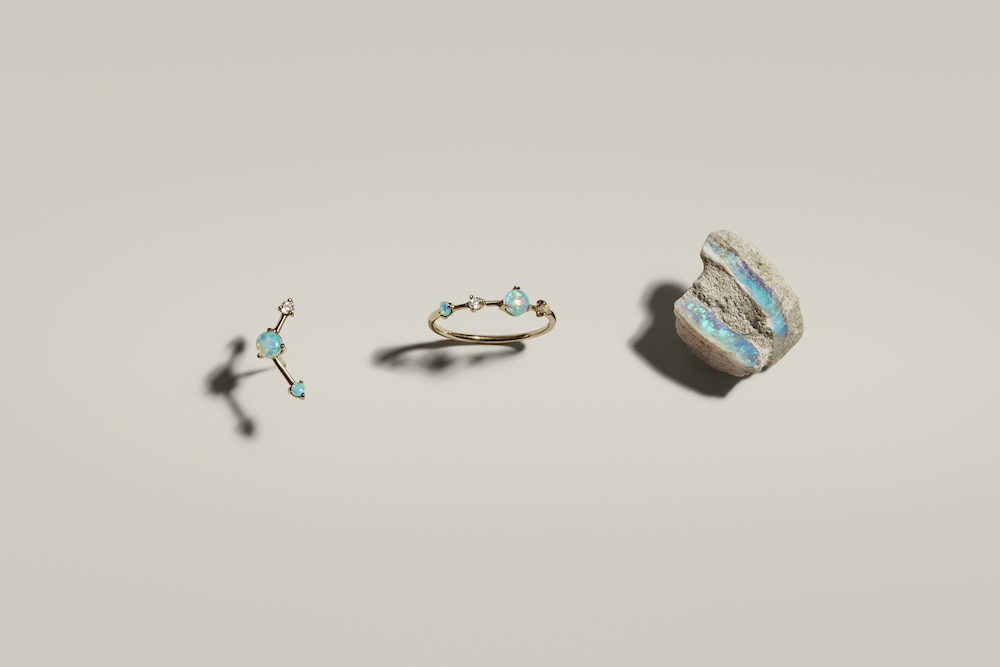

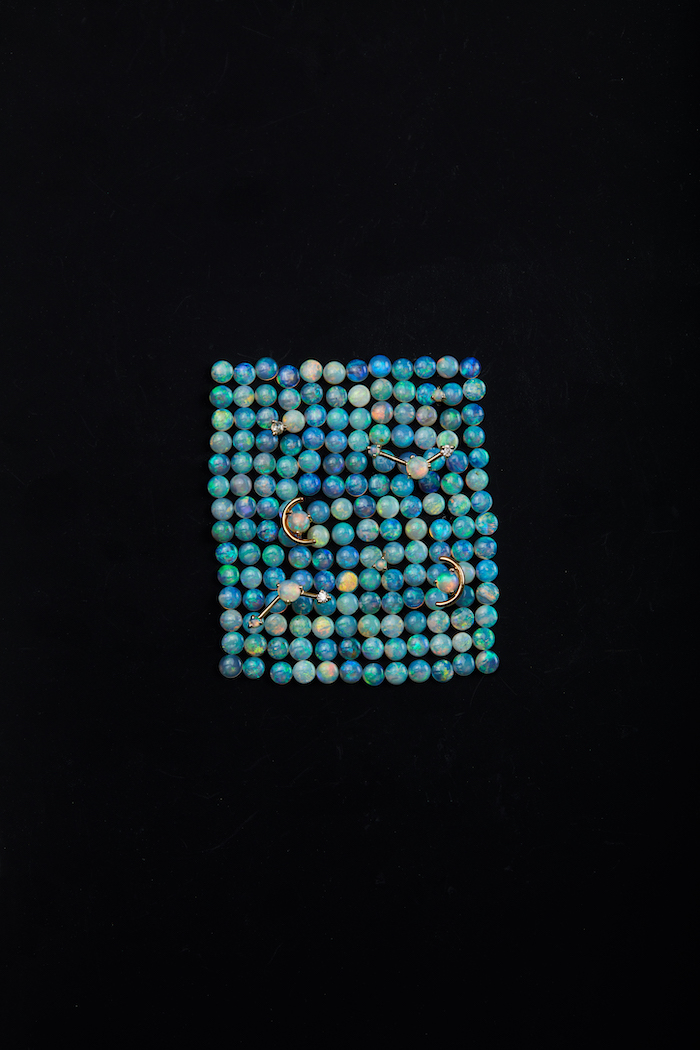

In September 2013, I released a small fine jewelry extension featuring opals and hints of diamonds in the delicate silhouettes of my debut project that allowed the stones to sing with a clean, graphic tone. This clicked and the collection was picked up by so many stores that I was overwhelmed with orders! Everything snowballed, and though I kept experimenting, WWAKE's fine jewelry is really what grew the brand into being identified as gemstone pieces with a careful sense of proportion.

I never imagined being a fine jewelry designer, but my approach to materials is to always let the material speak for itself. Gold and gemstones have a rich history, and using these materials opened a new vista. Society values gold, so people are at ease looking at my designs and feel comfort in integrating them into their lives. That’s a really powerful thing. When I started making wearables, I was making jewelry with “non-traditional” materials and felt limited in connecting with others. I do make traditional jewelry rooted in the experimental, and it’s subtle, but I feel motivated by the very real impact it can have.

I imagine a jewelry designer working alone. Was yours a solo effort in the beginning?

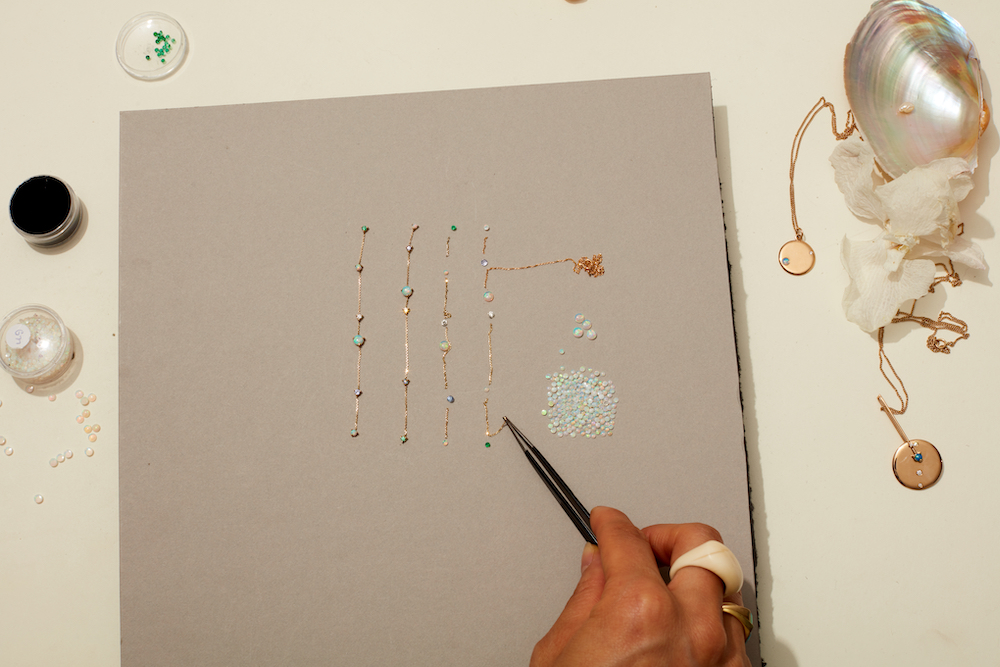

Oh my gosh, absolutely! I learned early on that I need time alone to incubate with my ideas. I didn’t set out to make a business or a brand; WWAKE developed naturally from my love for having a studio practice. I started WWAKE in my bedroom in 2012 and relished every minute. Mornings I would talk to store owners and do visual research online, then spend the afternoon making each piece by hand, on my own. I still love working with my hands. Before shifting gears from computer work to making pieces, I’d draw for an hour to meditate (highly recommend!) and then design late into the evening. It was the perfect artistic balance. Twice a year, I’d go to New York for bursts of social time: selling the collection to stores, meeting other designers and spending time with my long-distance boyfriend at the time.

Within the year, however, all of this needed to change. No matter how much I loved making the pieces myself, it was impossible, as stores were clamoring for their orders. WWAKE grew from a one-woman show to a two-person team, and now we’re a team of 21 in the New York jewelry district. It’s wild how things change, but I’m proud that each step has been organic.

I thought you started out in New York. How did you find your current space and what makes it function for you?

I started WWAKE in my hometown of Vancouver, Canada. I couldn’t get a job in New York, so I went back and forth between the two cities, mostly working out of my bedroom. I don’t need an elaborate set up for my work—usually just a sketch pad, some clay for 3D sketches, and a wall where I can pin my ideas. When I finally immigrated to New York and got a Brooklyn studio, I think I had four things: a single jewelry pin, a hand file, a handheld grinder from my undergrad in sculpture, and a table. It was ridiculously simple and I got a lot done with those items.

Our current space was the photography studio of my dear friend and collaborator Shay Platz, who had to move out of the city soon after I arrived. I took her space, made it a home and, over time, we’ve filled it with lush greenery and mineral specimens to make it an inspiring showroom. We’ve also built out a proper jewelry studio where five jewelers work on production and samples so I can stay close to how my jewelry is made. It’s amazing to work with other jewelers, solving problems that would otherwise remain abstract, to define and maintain quality as we strengthen our designs. We keep our jewelers’ process in mind, and an in-house studio gives us control in the sourcing of materials, rather than relying on a contracted jeweler for supply.

Fabled stories are attached to stones like the Star of India and Hope Diamond, as you said, we all have our own modest memories, right? What’s your philosophy about our relationship with jewelry, which might be even deeper after all this isolation?

Wow, yes, exactly. We see a lot of people buy jewelry for important milestones or investment simply because the materials stand the test of time. While clothes wear down overtime, I believe jewelry wears in with memories and reminds us of who we are. I think of heirlooms as relics of time, intended to last for generations, even after we’re gone. What do we imagine the future as, though? Who are we while making the decision to commemorate ourselves with these pieces?

Do you have a piece you wear everyday?

Yes, our Letter Necklace. It’s like a little loom with freshwater pearls and is inspired by the textile weavings of Sheila Hicks, who was my first inspiration for WWAKE. This piece has come full circle for me.

You have branched out a bit, haven’t you? Tell us about CLOSER, how it evolved and what’s different about it.

CLOSER is our sister collection. I like to call it the anti-WWAKE collection because it’s large, sculptural, pieces, the opposite of WWAKE’s airy silhouettes. But it does stem from the same philosophy of exploring the material with your hands: Each piece is a sheet of silver meticulously folded by hand, with an intention like origami. Each has a careful sense of proportion, reminding me of my very first collection, rooted in tenderness and touch, so CLOSER is an homage.

At first I was surprised that performance art was another focus of your undergrad, but now that we’ve talked, I realize that it’s actually an aspect of your design process.

I’m really wowed that you can see that connection! My undergrad sculpture and video performance work (which should never be seen by any human ever again!) was an ongoing study of connecting with an audience through my materials. I was interested in breaking the fourth wall and having the audience fall into the piece: subjects would make eye contact with the camera, and the voiceovers would place the viewer as director; meanwhile, video installations would live stream the viewer back into the sculpture itself. (This sounds creepy now that I write it!) I was also interested in the power dynamics between director, cast, and audience. Looking back, this was an abstraction of what I do with WWAKE—where jewelry is the connecting point. I’m very interested in the transparency of it all. I think it’s interesting to share how things come to be and invite everyone involved to participate.

Visit wwake.com to learn more about WWAKE's sustainability and sourcing // This article was originally published in our Summer 2021 Quarterly