Yinka Ilori’s eye-vibing public installations caught the attention of Her Majesty The Queen this year. She bestowed upon him the elusive title of MBE, a high-ranking award for outstanding achievements and lasting impact, remarkable for a millennial presenting critique of the same monarchy officially crowning him a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. Pay attention. You are now in the presence of—His Excellency.

Kristin Farr: Hello, Chairman, MBE. How must I now address you?

Yinka Ilori: [Laughing] I’m just a local lad, you know? I’m the same person. I’m more excited about meeting the Queen. I get to go to Buckingham Palace. When the Queen gives you the award, you can’t turn your back as you walk away. I’ve got to remember that, you know? I’m forgetful. I might take the medal and run. So many rules!

Did she notify you by phone?

I got an email from the government or Royal Family team, asking to confirm it was me, mentioning something special they wanted to give me. I thought, gosh, have I paid my taxes? I responded saying, “Yes, I’m Yinka,” and then they went quiet for about two weeks, so I called and asked them if I was in any trouble. They said, “No, no, it’s good news. Please wait.” And then I got their next email and thought, bloody hell, an MBE? Pretty nice.

And well-deserved. Your friend, another Yinka [Shonibare], also an MBE, has spoken about the irony of receiving the award from the very empire he’s scrutinizing.

[Laughing] His work talks a lot about the monarchy and post-colonialism and stuff like that.

Yours, too.

Yeah. It’s a weird one. I got a lot of mixed reviews from people wondering if I’d take the award, since many artists and musicians have turned it down. I was of two minds when I found out, and the first people I told were my family, who were extremely excited. Growing up where I did, in Islington, North London, there was no one with a title like MBE or OBE, or any Sirs. I think of my parents and their journey, where they’ve come from and what they gave up. I had to think of the bigger picture. I hope it paves ways, or provides inspiration for the next generation of young black kids who look like me. That, to me, is very, very important. I will always talk about my culture and identity in my work, and that’s not going to change, with or without an MBE.

There is some talk about changing the “empire” bit to something else—just take out the word empire, you know? The empire has done a lot of painful stuff, and I try to talk about these things in my work; subjects that are awkward, or painful to speak about, but turn them into positivity and celebrate my culture—whether it’s being British, or a Black British, or being proud to be a Black African. When I was young, being Nigerian wasn’t cool or celebrated. No one wanted to be African. So, when I have an opportunity to celebrate my blackness, every day, I am going to do that.

The media and society portray Africa as full of corruption and poverty, but they never want to show the goodness and beauty of the continent and what is there—culture, sunshine, beautiful people, so much heritage and things I discover when I travel to Nigeria.

Growing up, it felt like when you were outside of your house, you were British, and when you were at home, you’re Nigerian. You couldn’t celebrate both; there was no middle meeting point. It was one or the other at certain times. We were lucky because my mom and dad made sure we knew who we were and where we came from. We ate Nigerian food and they’d speak to us in Yoruba. I’m always grateful. They’d say, “We don’t care if you’re born here. You’re Nigerian and that’s it.”

When did you first travel to Nigeria?

I was 10 or 11 years old, and it was my parents’ first time back after being in London for so long, this time with their children, and taking us to see their parents, nephews, cousins, and other family. It was quite a special moment.

They had left somewhere they’d known their whole life to start a family in an unfamiliar place, which is new and scary, and I’m grateful. When the BLM movement happened recently, my mom told me about moving to London, and how she and my brother went to view an available house. When they arrived, the person told them no Blacks were allowed and shut the door on them.

When you hear those stories and know what they’ve been through, it makes you angry. I pour the anger into my work and celebrate my culture as much as I can, and I do it in a way that’s very unapologetic. It’s who I am.

Unapologetically bold. Tell me about the names of the designs in your new collection.

I’ve got a huge archive of patterns I’ve created over the years, through travel, just walking around London or talking to people. I’m always taking stuff into my head and then putting it into sketches and patterns. This collection was inspired by my visit to London City Airport, and its history of the Royal Docks, and what it was used for in those times. It was a place where people imported things like rum from the Caribbean, or elephants for circus fairs, that kind of thing.

Looking back at that, and knowing Britain wasn’t built by just Brits alone, but by all different people and cultures, I was looking at the cultural exchange that the British people have with other countries.

The print that’s called Omi Omi means “water, water.” The blue squiggly lines represent the Thames and the water surrounding the Royal Docks. There’s an oval shape mimicking rum barrels that came from the Caribbean, through the Royal Docks and were sold here in the UK. There is always a message, meaning and story behind my work.

I noticed another abstracted symbol in the rug…

The pineapple.

Yes!

It comes from the Royal Docks shipping in fruit and veg from different countries, like bananas and pineapples, because we can’t grow those here, can we? No, we can’t!

Ope means pineapple, and is again paying homage to everything that is imported from different parts of the world.

You sourced Dutch Wax print fabric in your early work, and the story of that textile industry is such a cultural phenomenon.

It was a huge part of my upbringing and it wasn’t until Uni that I discovered it’s not from Africa. It’s produced in The Netherlands by a company called Vlisco, but they make their money off West Africa—Nigeria, Ghana—they are the biggest consumers and buyers. When I discovered that, I thought, bloody hell, this is crazy. There’s no link between them at all, but Vlisco is making money off my peeps, you know? But I also love the fact that Nigerians made it their own. It was something they could identify with West Afridan culture. At a wedding or church service, or any special occasion, people wore it as a collective. It allowed them to take over public space, in halls, or churches or corner shops, and when they walked in, people were already wanting to speak to them and engage with their culture, and understand what they’re wearing and why.

I love that fabric can give people a sense of belonging, and that’s what the prints did. I identify Dutch Wax prints with happy memories and positive times within my life. The prints have meanings and messages, and it’s powerful that fabrics can talk to you; there is a hidden message in those textiles that can be found without even speaking to the person wearing it.

Not a lot of people are aware of the Dutch Wax history, and it’s messy, so that’s why I’m trying to design my own prints now, and tell my own story. People have been asking to buy my textiles by the meter, so that’s something I might do next year.

It’s worth noting that Vlisco originally appropriated their style from Indonesian designers, so the plot is thick. From you, I learned about Swiss Voile lace, a textile detailed for the Gods.

Swiss Voile lace is crazy. When we were young, my mom and dad would have friends come ’round and sell them the lace from Switzerland, or the best jewelry from Dubai. Socializing was quite a big thing for my parents, and all the men wanted their wives to be to have the best Swiss Voile lace or the 24 karat gold from Dubai. It was really a serious thing, going to a party, because everyone wanted to be the best, and they’d spend 800 quid on the 6-yard Swiss Voile lace with amazing weaves and really small diamantes all over, so that when the camera guy shines his light, you’re blinging. It’s a proper, proper thing.

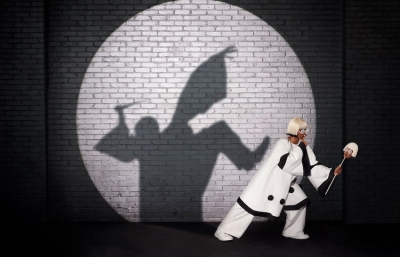

An early career catalyst was the discarded chairs you would find and redesign, the reason you’re the self-described Chairman. I noticed some had their backrests removed, and I know each chair is a story about a person you know...

The chairs started in Uni and paved the way for my career to move into design. I was the guy who loves and collects chairs, and “re-loves” them, and tries to tell a narrative within them. Most of the chairs do have backrests, and all have their own parable narrative. One from the If Chairs Could Talk collection speaks of this young guy I went to school with. He didn’t really have a backbone. He was always the person who could never say no, and found himself in a lot of trouble when he was always saying yes because he wanted to fit in. The backrest is there, but in a position that isn’t really comfortable. The chairs have common themes about identity, culture, hierarchy and status, and they’re embedded with a parable. You need to read the parable over and over to understand the messages, just like a book, even though some are only one sentence. They come from my parents, who told them to us growing up.

With the chairs, what I tried to do was ease the audience into my work and world with the colors and patterns, so the first thing they’d do is smile. And that makes them feel more comfortable, and then, when they understand the parable, that’s where the idea and thought process of the chair’s meaning comes through. It’s a bit more than a colorful chair. It has a message and meaning.

For me, the first thing is to engage with an automatic smile, where you’re smiling without even knowing it. It’s like when you’re on the bus and you laugh to yourself. We’ve all done it. You’re not going mad, even if people might think you are. And that’s what my work does to you.

yinkailori.com // This article originally was published Spring 2021 Quarterly edition