After quickly flipping through an exhibition catalog, an image by one particular artist stuck in my mind. This painting of a precocious young man, whose dignity rose above a cluster of mirrored spheres crowding his neck made me hungry to see Robin F. Williams’s paintings in the flesh, and I trekked through a New York snowmageddon to attend her opening at PPOW Gallery in Chelsea.

In person, Robin’s work emanates that magical physicality of pure, unadulterated paint. The delectable surface oozes with the confidence and generosity for which anyone who has dragged a brush across a canvas or wall strives. Beyond such visceral qualities lies subjects both witty and revelatory. Robin uses her canvases as personal discussion forums where she questions the cultural expectations and common societal portrayals of gender.

In her body of work, Sons of Pioneers, Robin switches up the gender roles typically found in great historical painting. Unapologetically, she depicts her men occupying the same visual language associated with the feminine: languid, exposed, and passive. For example, in Cave Painting, Robin has replaced the classic Odalisque with another art history stereotype: the hero-male. In Robin’s compositions, the men lounge lazily and with aimless intent in the very frontiers of which they are supposedly the conquerors. One wonders if perhaps this is a more accurate representation of the frontier: a borderline homoerotic camping trip which, through creative embellishment and an elaborate game of telephone, has been handed down to us as tales of danger and masculine adventure.

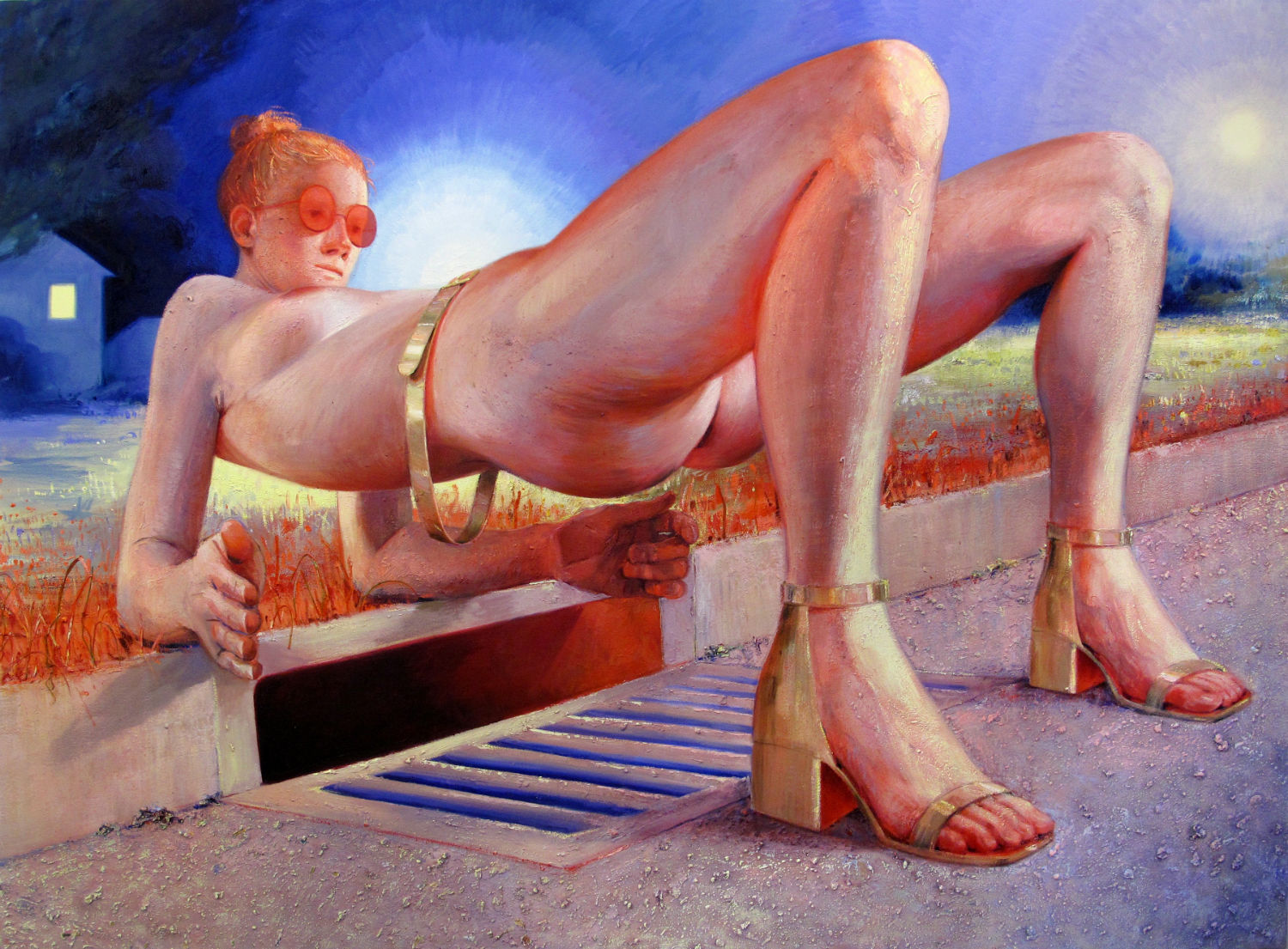

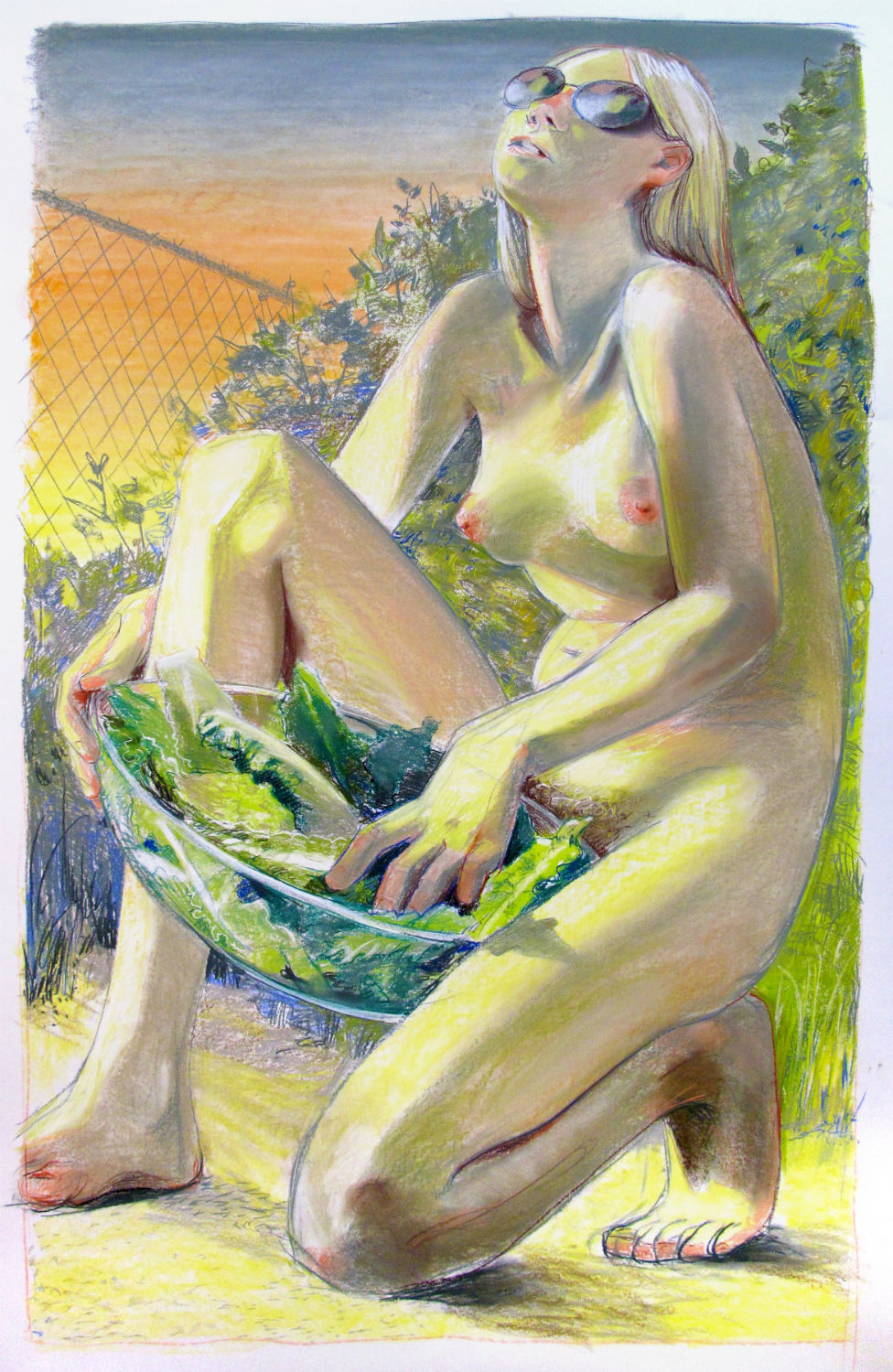

I dropped by Robin’s Brooklyn studio as she began a new series. After years of building toward the territory, she’s rolled up her sleeves to boldly tackle female sexuality. With wicked twists of wit and humor, Robin plays with feminine mystique marketed to women through commercial products. Approaching this, fully aware of the multiple cultural snares and potential pitfalls in depicting women’s sexuality, she toes this treacherous line mostly by using herself as a model, and in these “self-portraits,” brilliantly avoids perpetuating the very objectification of the women she calls into question.

Read the full interview in the August, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

David Molesky: What has inspired your new group of paintings, like this one with the girl and the salad.

Robin F. Williams: Women are marketed certain products as replacements for their own sexuality. Do you remember that ’90s Herbal Essences commercial where women are washing their hair and simulating an orgasm in the shower? Or those yogurt commercials where women moan “it’s sooo good.” There’s also that popular meme of women smiling and eating salad. The woman in this piece is a bit sexually confused and hasn't found a place to put her desires. She’s being told it’s okay to love salad, so she’s furtively testing it out. Maybe she’s even fetishized it. It’s become an “acceptable” place to put her lust. I’m interested in feminine do's and don'ts; doing some things right and some things wrong, or the right things done in the wrong way.

The current series in production seems to have a feminist message. Has this always been part of your work?

In subtle ways, yes. In school, I painted a whole series of Lolita figures, but I started to feel like I was exploiting that image without being all that subversive. I realized my interest was more about feeling like an adult when you are a child, or vice versa.

As these early figures got older, my next series became teenagers on the cusp of sexuality. I focused on how myths informed their roles, the ways that they were allowed to become adults, and how that fit into the broader myths they believed they had to inhabit. They needed to feel grounded by these myths, but that was complicated. There was a lot of problematic old Americana inherent in these roles. I knew I wanted to talk more about sex and feminism and female experiences, but I wasn’t fully there yet. The [paintings of] men were an important bridge. Now I’ve fully arrived at those ideas.

I like how you talk about myth as a structure that people try to grow into. How do you identify these myths?

They are the stories we use to explain what we can’t understand. Why do we cling to the idea that femininity and masculinity are hierarchical and distinct? It’s that essentialist question: is there something eternal about that dichotomy? I tend to think that these ideas about gender are very fluid, but I wonder why we hold on so dearly to the idea of feminine and masculine as separate. Maybe so we can rank them or eroticize them. I don’t know, but I like to run experiments with the paintings.

There are a lot of female painters who paint themselves in a way that is a continuation of what’s been called “the male gaze.” I definitely don't see you doing that.

Part of the reason I’ve waited to paint women is that I didn’t yet have a language to address that issue. Images of women get easily sublimated into something one dimensional because of the very problem of a woman's body reading as a cultural signifier or archetype or mythological marker. Women’s bodies are used in so many stories and images. They are used as a vessel for the culture’s desires, a bit like the woman in my painting is using that salad.

Society has just accepted its use and is rarely critical of what that does and how we think about it.

Totally. As a result, I have to make work about that problem. If that problem is preventing me from making work, then I’m left with little choice but to make work about the problem. I'm not the first to do it. There has been lots of feminist work on that subject. But as long as the problem exists, you’ll be hearing from us.

Most of the artists who have tried to tackle this have done so with conceptual art. You have managed to do so with gorgeous paintings and at such a young age.

I think conceptual work on these issues is really important. It just hasn’t been my story. I started oil painting in kindergarten, and my whole life has been experienced through that practice. It’s also a method I have come to consider very conceptual. Having had two solo shows before I was 27, it made sense that I was making paintings of children. It was a period when I felt a little like I was pretending to be an adult. It somehow seemed like an act, being a professional artist, even though I had literally been working on it since I was five. I was confident in my skills because they were second nature at that point, but the role still felt foreign. I think that goes back to not fully understanding myself in the context of all the myths I’d internalized about artists and womanhood. The paintings helped me resolve those misunderstandings. They still help me.

Are there female painters who have influenced your trajectory?

Most of my female influences are contemporary. When my high school art teacher showed me Manet’s Olympia and explained to me why it was so controversial, I got really excited. Manet was referencing Titian, whose women were boneless, passive, sexy and mythical. Then Manet decides to kick off modernism by painting a prostitute looking you straight in the eye. She had this awesome toad-like hand covering up her genitals. Manet was like, “Hey guys, women aren’t an idea, they’re actually people,“ and everyone just freaked the fuck out. And I thought, I want to do that!

Artemisia Gentileschi, Vigee Le Brun, and Mary Cassatt are significant historical female painters that come to mind.

Mary Cassatt interests me because she only painted mothers and children, though she was not a mother herself, and probably couldn't have been to be the success that she was at the time. I like how she had a real reverence for femininity. She wasn't trying to dress up femininity like masculinity to make it valid; she just made it her subject.

Sylvia Sleigh is another. She was really democratic with her marks and also her way of cultivating desire through both male and female subjects. Her paintings are so 1970s but still so relevant to me. She really influenced my body of work about men, even though the sexual element wasn’t at the center of that work. I wanted to talk about dominant American male culture and because people make homophobic judgments about men in repose, I didn’t want that topic to become the entire conversation. It was part of what I was talking about but not nearly everything.

That’s a good point because the sexuality wasn't glaringly present; it made it more heterosexual in a way. That element of shyness made it feel very real.

These new paintings of women are about having to fulfill impossible expectations. Before, I was thinking about what these expectations might be for American men. How can they accidentally enter a place that is totally forbidden, and why are those places forbidden? What are the bodily signifiers that place them in hostile territory? Maybe a man is just having an authentic experience with himself, and suddenly that act becomes shameful once there is an audience. I wanted the men in the paintings to appear carefree, so any perceived shame would be an issue for the viewer. I had several straight men flat out tell me they couldn’t buy this work because they wouldn’t want people getting the wrong idea.

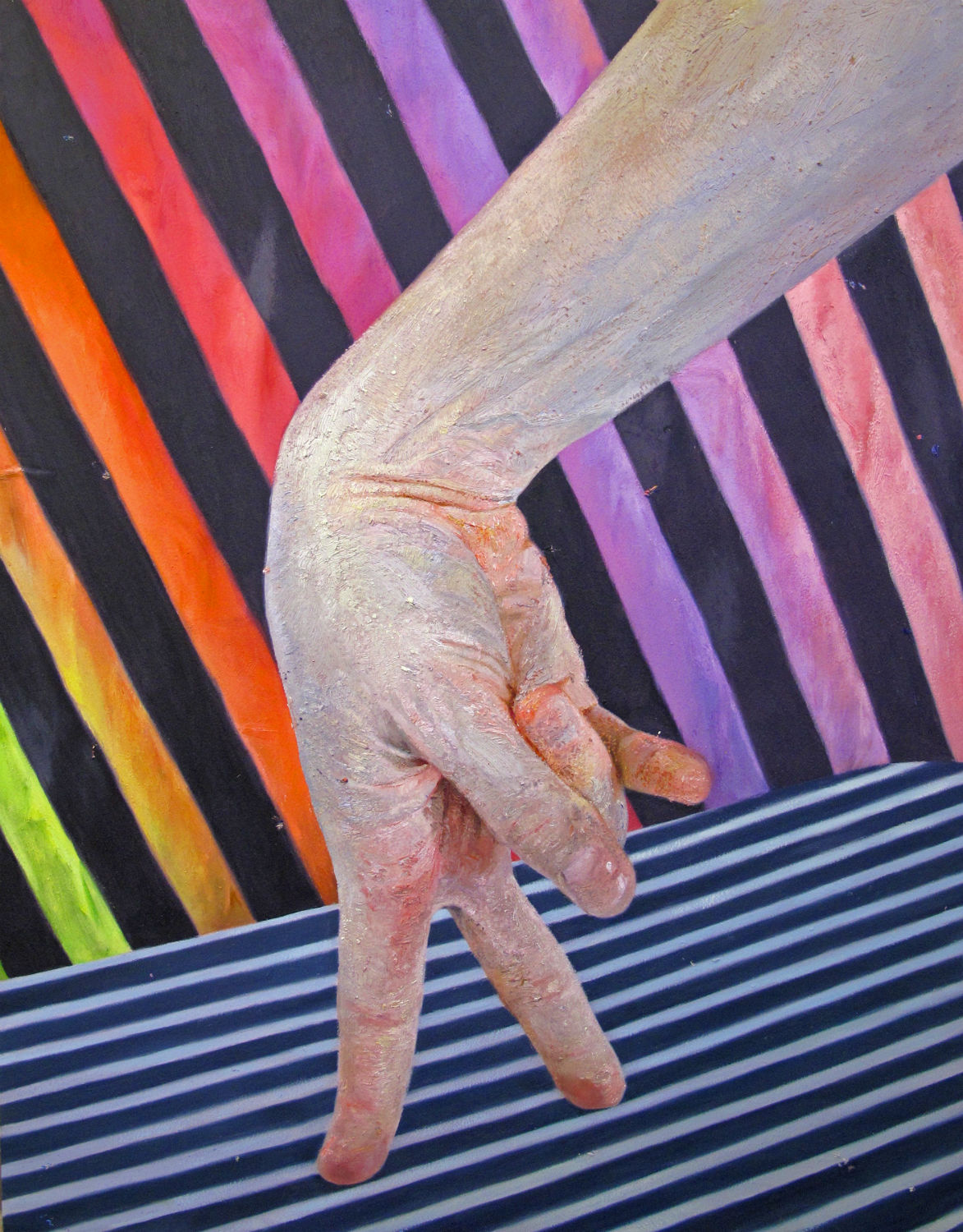

I read a great essay about the way that Artemisia painted hands as if they were human hands as opposed to boneless, dainty and demure. You look at all the other Renaissance and Baroque era painting of women's hands, and they just seem like they have never been used. I think about the foreshortened toad hand on Manet’s Olympia as a comparison; the definition of labor. In my work, realism becomes a foil, so I can render a certain body part or environment in an unexpected way.

Your work does have a pervasive sense of humor.

More and more I am trying to let that come in. I’m always trying to become less cautious in general. It’s so nice to get older because you just worry less. It’s freeing.

How do you navigate decisions about subject matter? Where do you go for feedback and council?

In the last year and half or so, I've become part of a women’s critique group. We take turns hosting at our respective studios and often invite other artists to come for specific visits. So it’s always a trusted group with an ongoing knowledge of each other’s work. It has been invaluable.

It’s always women?

Yeah, it’s really great. A friend and colleague who originated the group invited me. I wouldn't be opposed to a coed crit group but it’s actually been really helpful this way, very validating. I've been hanging out with a bunch of artists and it happens to be mostly dudes, or I get invited to an open studio and it’s all dudes. That’s great. I want those perspectives, too. I’ve had invaluable critiques with men. I just need practice being so rooted in my own experience that I bring that with me into every environment. Female artists with sustained professional practices are still very much in the minority in the art world. We have to seek each other out.

----

Originally published in the August, 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our webstore.