Almine Rech Paris, Turenne is pleased to present Home is Not a Place, Jess Valice’s second solo exhibition with the gallery, on view through July 26, 2025.

In this exhibition, Jess Valice delves into the complex and often contradictory nature of home, a concept that has long fascinated philosophers and poets. As Nietzsche and Rilke explored, it can be a source of comfort and belonging but also a realm of potential alienation. Her work grapples with this duality, reflecting on the yearning for a safe haven alongside the potential for even familiar places to become imbued with unease in the face of loss and change. The artist literally invites us into a unique installation, a representation of her bedroom, the ultimate symbol of sanctuary. Bathed in deep maroon-colored, the room evokes the primal safety of a womb or the rawness of an open wound. Opposite the bed, a video projection presents a sun-drenched backyard where the delicate chirping of birds creates an atmosphere of exterior peace and serenity – it’s the actual view from her window.

The artist literally invites us into a unique installation, a representation of her bedroom, the ultimate symbol of sanctuary. Bathed in deep maroon-colored, the room evokes the primal safety of a womb or the rawness of an open wound. Opposite the bed, a video projection presents a sun-drenched backyard where the delicate chirping of birds creates an atmosphere of exterior peace and serenity – it’s the actual view from her window. This tranquil moment is an interplay between exterior peacefulness and interior numbness. Visitors are invited to sit on the bed, stepping into the artist's perspective. This dialogue continues in an adjacent room, where a diptych self-portrait captures her lying in bed, further probing this tension. The asymmetrical composition exacerbates the loneliness and isolation that follow a traumatic event. Unfinished lines on a pillow, resembling cell bars, evoke the feeling of being trapped in grief, while a rust-colored stain on the bed creates a disturbing echo of a crime scene — une petite mort (French for ‘a little death') that speaks to both the end of a relationship and the intimacy it once held.

"Home has never felt like a fixed place," Valice confesses. "I’ve always carried a sense of displacement with me."1

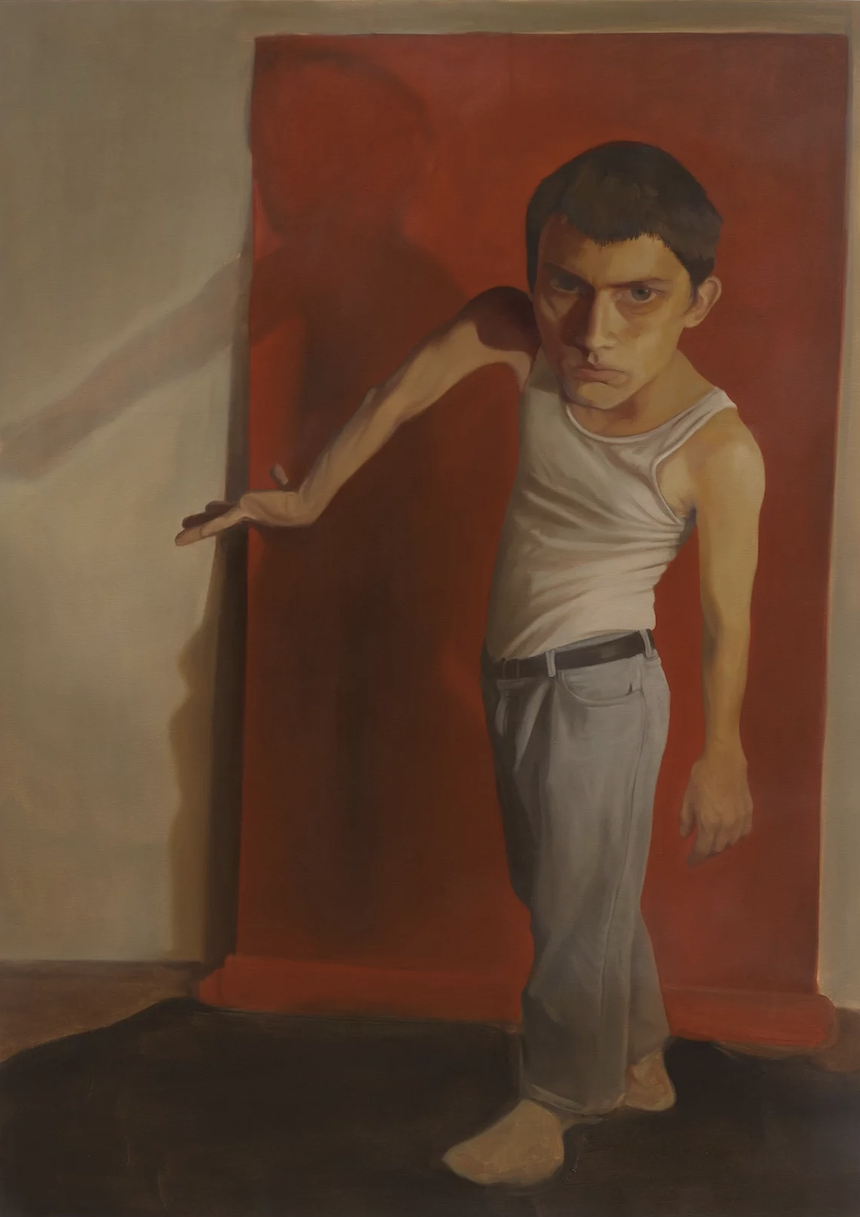

Recent events, including this year’s Los Angeles fires, the passing of her father, and the dissolution of a romantic relationship, have collectively intensified the artist's quest to find what gives us emotional grounding, compelling a confrontation with the fundamental values that remain when physical spaces and intimate bonds are severed. Part of it is friendships, showcased by portraits of her close friends, each one based on photographic references captured by her childhood friend, Jack Tashdjian. In Kuba II the young man with blond curly hair against a bright red background acts as a beacon of vivid energy within her otherwise more monochromatic paintings, hinting at how the presence of loved ones can illuminate the spirit with warmth.

Yet, Kuba’s sanpaku eyes — a Japanese term for eyes with visible lower sclera, suggesting imbalance — add a layer of intrigue to his otherwise vibrant presence. This feature, which the artist instinctively captures in all her subjects, offers a glimpse into a person's lived experiences, current struggles, or quiet melancholy. She feels deeply drawn to these individuals in real life, often forming effortless connections that evolve into genuine friendships, as if these eyes were speaking for themselves and revealing one’s sensitivity.

Each painting invites us into an open-ended narrative, resonating with Francis Bacon's notion that "the job of the artist is always to deepen the mystery." Valice’s figures appear both tormented and introspective, as if caught in fleeting moments of the past. Their bodies and faces, subtly distorted, embody the way reality itself warps under the weight of significant life events. In works like The Friend Who Brings You Congee, their fragility is palpable — nude and exposed, yet silently wrestling with their own thoughts. When making this piece the artist was thinking about Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking, particularly the passage in the book describing a friend bringing her congee (a Chinese rice porridge). This act of kindness reflects how profoundly meaningful such simple gestures can be when navigating the overwhelming physical and emotional effects of grief.

In the still life Chicken Broth, a raw chicken is displayed next to a steel pot with clinical detachment, its flesh is a stark metaphor for the artist’s own vulnerability, laid bare for the viewer. But it is the implied scent that is here to truly transport: the faint, anticipatory aroma of simmering broth, a smell that clings to childhood kitchens and sickbed comforts. Even for the artist as a vegetarian, it unlocks a floodgate of associations and emotions — a soothing sensation that spreads beyond the stomach, a feeling of being cared for, of returning to a place of origin. It is her Madeleine de Proust — a sensory trigger for vivid memories that Marcel Proust describes in In Search of Lost Time.

Driven by her lifelong fascination with psychology and neuroscience, she passionately explores the multifaceted nature of home, bringing us into her deeply personal doubts and existential inquiries. Recalling Rilke's concept of "world-innerspace" or "the house that stands inside me" transcends physicality, representing a sense of belonging rooted in culture, religion, or personal experience.

'Home is Not a Place' encourages us to confront our inner shadows, to find beauty in fragmented memories and to discover that home can be found in the echoes of the past and the whispers of the heart.

— Lisa Boudet, writer and curator