"Whatever it is you 're seeking won't come in the form you're expecting." If you are going to talk about a little shop in the middle of rural Japan, left abandoned only to contain an array of past treasures and tell the story of the husband and wife who transformed it into a viable sort of art installation, then this referenced Haruki Murakami quote is apt. Japan has an energy, an earthy supernaturalism, that makes its magical realistic qualities emerge in the most mundane of situations. In the tiny village of Kawamata on the island of Shikoku, Rufus Ward and his artist wife Eri Itoi have created the painstakingly detailed The Rough Shop, a found object paradise that combines a chance discovery of an untouched store in rural Japan with the passion of two artists who could present the shop as performance. And that is just what it is, a performance filled with memory.

Evan Pricco: In the simplest terms, what have you turned this shop into?

Rufus Ward: It is an installation, a shop, and a kind of museum. We made a decision to relocate as much of the original shop as possible to our exhibition space, which is in our house. Its name, Rough Shop, is based on the original owner's name, Arakawa, which translates as a rough or wild river (Ara means rough or wild and Kawa means river). This was not going to be a normal shop. We wanted it to be wild, intense, crude, and honest.

We took the shop's original stock as well as its furniture, lighting, decorations, and atmosphere and rearranged them in a different way, in a white-cube-style exhibition space. We tried hard to preserve the original shop's look and feel but inject it with new energy and style. I usually paint rooms and interior layouts (I am more painter than a 3D artist) and I fill these spaces with odd combinations of things to create a certain mood. The Rough Shop was going to be a physical embodiment of one of these paintings. I wanted to recreate the mood of the original shop, the awkwardness, strangeness, and overwhelming density of the goods, but weave it all together into a mash-up of museum, gift shop, and artwork.

We haven't decided how long to keep The Rough Shop but as the original stock disappears (being all vintage, there is a limited amount) we will fill the gaps on the shelves with artifacts made by ourselves and other artists or makers. We really liked the idea of putting handmade crafts and art objects alongside the other stuff. It will be like an exhibition within an exhibition. It gives it all a great balance and a strange synergy and hopefully will pique someone's curiosity.

Your dad sort of walked me through this a little, but this shop that you took over basically stood unchanged, unattended to, for decades?

Well, it was a shop but also a house, and the owner, Mr. Arakawa, moved out around fifteen years ago. The shop had been closed for perhaps twenty years before we took it over. The interesting thing is, this shop had been around since the Showa era (at least since 1945) and probably had its heyday around the 1980s when the tiny village of Kawamata was prospering from the lumber trade and Japan was in its “bubble economy.” The goods inside reflect this long postwar period although the majority of the items seem to be left over from 1980.

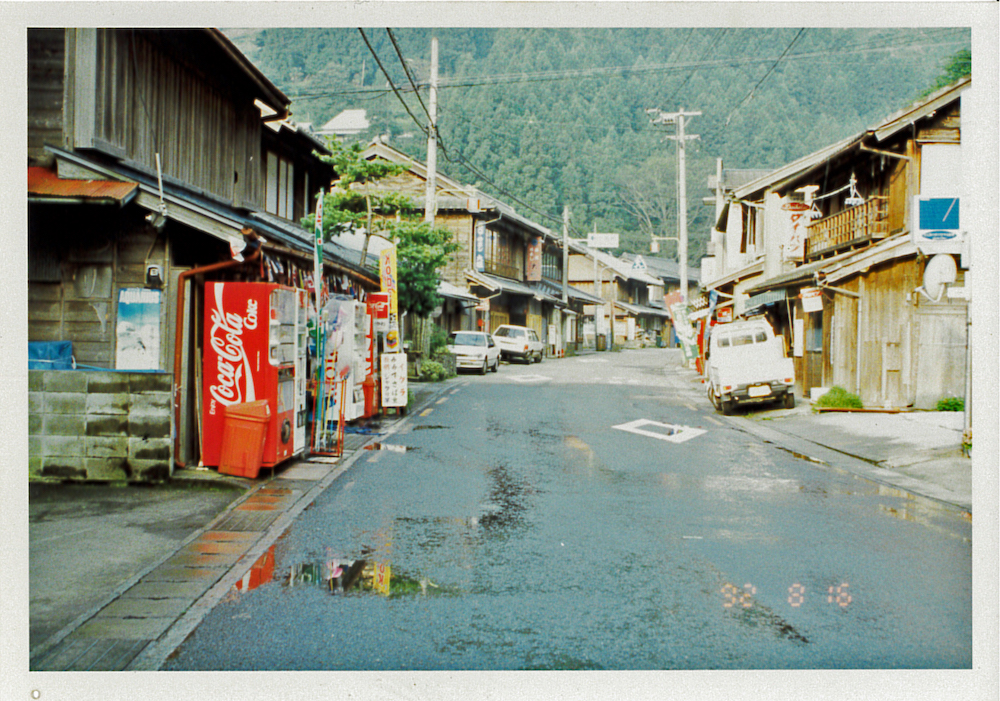

We first came to know about this shop when we moved into the tiny village of Kawamata. Kawamata is basically a handful of houses perched on the edge of a river, crammed between two huge mountains. We moved into an old Japanese sake shop and lived there for a year while we searched for a house to buy. I was jobless so I often took walks around the area taking pictures and writing articles for the Kamiyama website. The main street had a lot of empty properties but this shop stuck out mainly because it looked as if it could still be open for business. Outside, there were three or four capsule toy vending machines and a big old drink machine. Looking through the shop windows you could see piles of plastic model kits, stationery, radio-controlled cars, rubber gloves, toys, fireworks, and many strange things hanging from the ceiling. Almost everyone said, "There's got to be treasure in there!" We just loved the idea of this toy shop existing in such a tiny place in the middle of the mountains and trees. The randomness of the items and how they were all crammed together in this place was really fresh. It felt like a time capsule or a museum and it was inspirational and really resonated with us.

The randomness almost seems like a gift, really providing you with an option for any direction you chose.

I spent all my free time making separate piles of things. It was an agonizing process because I wanted to document everything but we were getting help with the clearing-out process from the town office, so I had a deadline to sort things out. I didn't know where to begin but once I got started it quickly became very addictive. Each day, I had no idea what I was going to find and how I was going to use it. Even the smallest, most worthless items like a cutout fragment of newspaper became extraordinarily interesting. Why did the owner cut this out? What does it mean? How should I display this? How does this fragment relate to the other newspaper clippings in this envelope? Why are they in this "Happy Birthday" envelope? Why are these handwritten notes in a glass jar wrapped in plastic? Why did he have so many plastic bags? I was tumbling deeper and deeper into a rabbit hole of trash. I was an ultra-focused, hyper-attentive rubbish hunter wallowing in an unknown dead man's life work. Of course, I was also asking myself existential questions like, “Is this what is left of us when we pass on? If I evaporated at this precise moment, what kind of mess would I leave? What kind of picture would someone have of me?” The surreal qualities of house-clearing in the middle of the mountains in Japan, particularly if you are creatively inclined, are not lost on me. I will probably have to write a book about it in the future.

It could have lasted six years because I would come home exhausted mentally as well as physically, but amazingly I got everything sorted in two months. Towards the end of the two months, I became less worried about keeping things that might be useful for making art and ended up just throwing anything I could get my hands on into the rubbish bags as fast as possible. I was probably a little reckless and threw out some things I shouldn't have, but thankfully I did save a stack of fascinating drawings made by Mr. Arakawa when he was a kid. These are drawings he made at school so all of them are dated on the back. They are from around 1945, just about when the war was ending so they all have naive, nationalistic vibes to them. Among the sketches of soldiers and airplanes are lovely scenes of everyday village life, people walking, animals, buildings, and plants. All of them are drawn in crayon on aged Japanese washi paper with the lovely carefree purity of a child's hand. We want to exhibit them in the future. A book would also be great.

Another highlight of the initial search was a large locked safe which we spotted in the corner of one of the rooms. When we finally got it open it was filled with Mr. Arakawa's personal stamp collection! Apparently, back in the 1980s, the Japanese government said stamp collecting was a good investment for the future. The problem was, everyone started collecting so the value of the stamps did not increase. Still, they are beautiful and we want to find a way to use them.

(Original photo of the Rough Shop, circa 1980s)

The idea was always to keep some of the original items, like the stamps as artifacts.

Yes. We wanted to keep as much of the original shop as possible, but also try to create something new and thought-provoking. The mad variety and randomness of the objects in the shop was definitely something we wanted to make use of, but instead of using them all, we wanted to edit the selection and carefully pick out the items, or combination of items, that really intrigued us. Once we had our final cut, then we could start building and placing things, making weird connections between objects, and really start setting the scene. Familiar but offbeat was our plan.

How did you find yourselves in this particular town on the island of Shikoku? When we speak about art in Japan, we stereotypically think of Tokyo or Kyoto. So in Kamiyama, what sort of arts and culture was there before you got there?

The artist-in-residence program is the biggest thing on the calendar as far as art and culture go in Kamiyama. It was started in 1999 and it is still the highlight of the year. Three artists spend two months from September to November working and living in Kamiyama. The locals work with the artists helping them realize work for the final exhibition which takes place in early November. It's an immersive and intimate experience for everyone involved, and it is amazing to get to know so many different artists in such an out-of-the-way place. After the residency has finished, the artworks are usually stored in an abandoned junior high school, but there are also quite a few permanent sculptures lingering in the forest, covered in moss and slowly disintegrating.

When we arrived in Kamiyama, apart from the artist-in-residence program, there were no independent galleries, artist-run spaces, art museums, experimental collectives, or anything like that. It was really quite refreshing! The town did, however, have a dusty museum dedicated to farming and forestry, and the sheer range of ancient farming equipment on display was quite impressive.

With Japan's reverence for a traditional way of doing things, and in such a small town, what was the reaction to The Rough Shop, where you just let the art grow from within?

I think the initial reaction of most people was confusion, followed by disbelief, followed by excitement. Rather than promoting this as an exhibition or art installation, we decided to just give it a name and tell people that everything was for sale so everyone could relate to it in their own way. Actually, the visitor demographic in Kamiyama is so broad. It's what makes having exhibitions here so fun. About seventy percent of the population here is over sixty, and probably most have never been to a contemporary art exhibition. There are also a lot of newer, younger immigrants who are focused on their own lifestyle choices like farming or I.T., but even among these new settlers, I would say only a tiny handful have an active interest in contemporary art.

A lot of local people we spoke to remembered visiting the original shop as children. They spoke fondly about it as a magical, wondrous place filled with temptations. I know some people even traveled from Tokushima (a good one-hour drive) to visit, so it must have been well-known and popular back in the day. When we first mentioned that we bought the shop a lot of people were intrigued and wanted to know what we were selling. They remembered particular toys that they always wanted as kids and they wanted to know if they were still available.

The Rough Shop can go in so many directions, even a quiet dissolution. But you can evolve with the space, and have certain artists collaborate with the idea of the space, too. How have you imagined its future?

We want to get more artists and makers involved but the artworks or crafts we choose need to resonate in a certain way with the shop items around them. These objects will not be displayed to draw your attention to them. They won't be highlighted or the main focus of the exhibition but rather blend in and hide away, hopefully adding a different level of interest to the shop setting. They will be for sale like the other items, and in the end, once they are gone, be replaced with new artworks or crafts. In this way, the exhibition within an exhibition can change and transform the shop into something else. That is our addition to The Rough Shop's heritage.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2023 Quarterly.