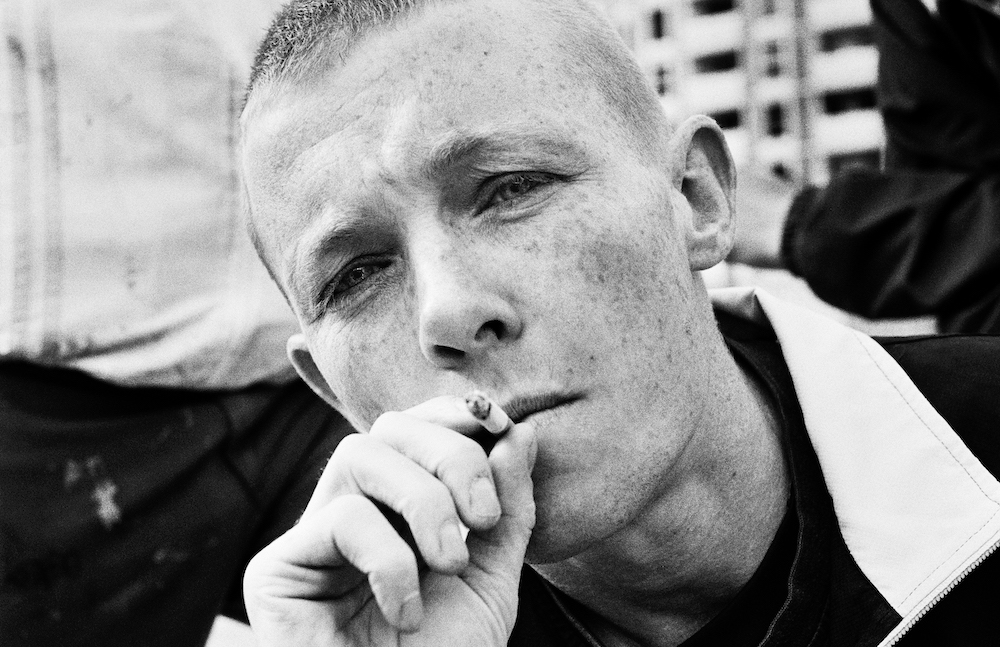

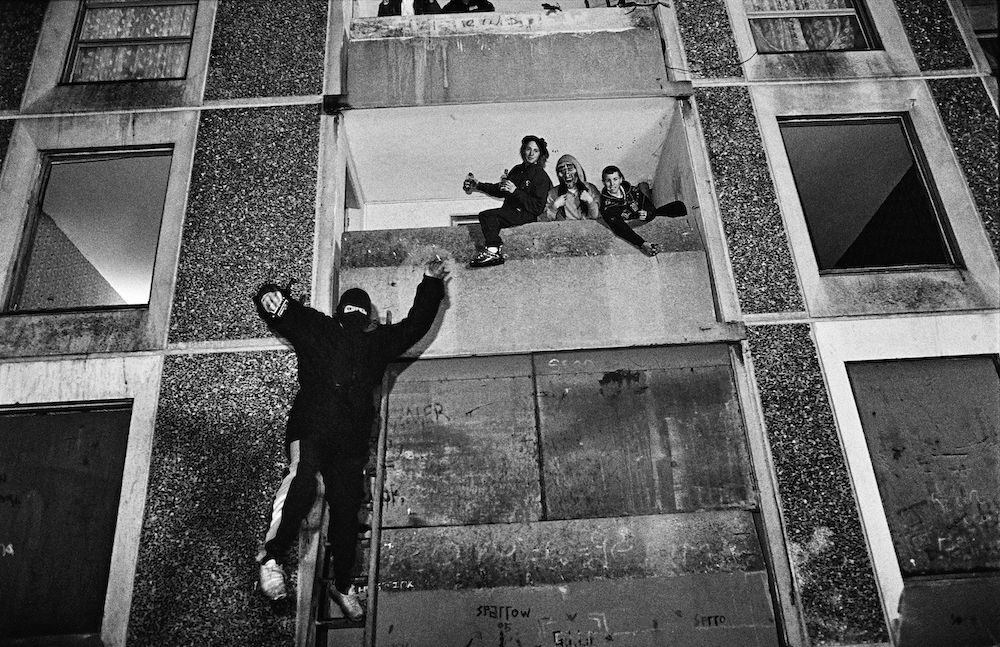

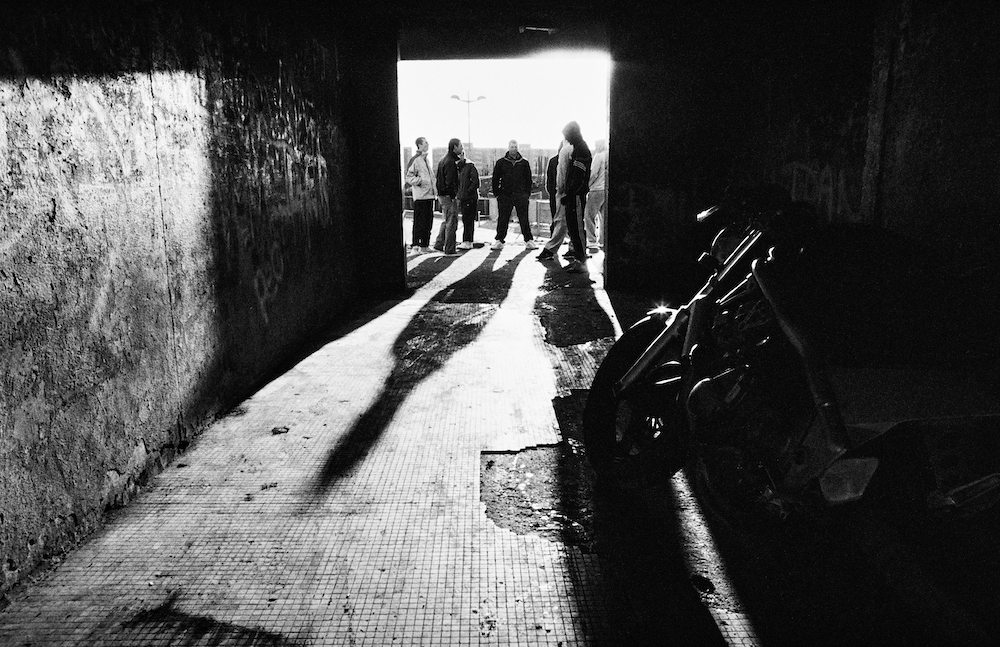

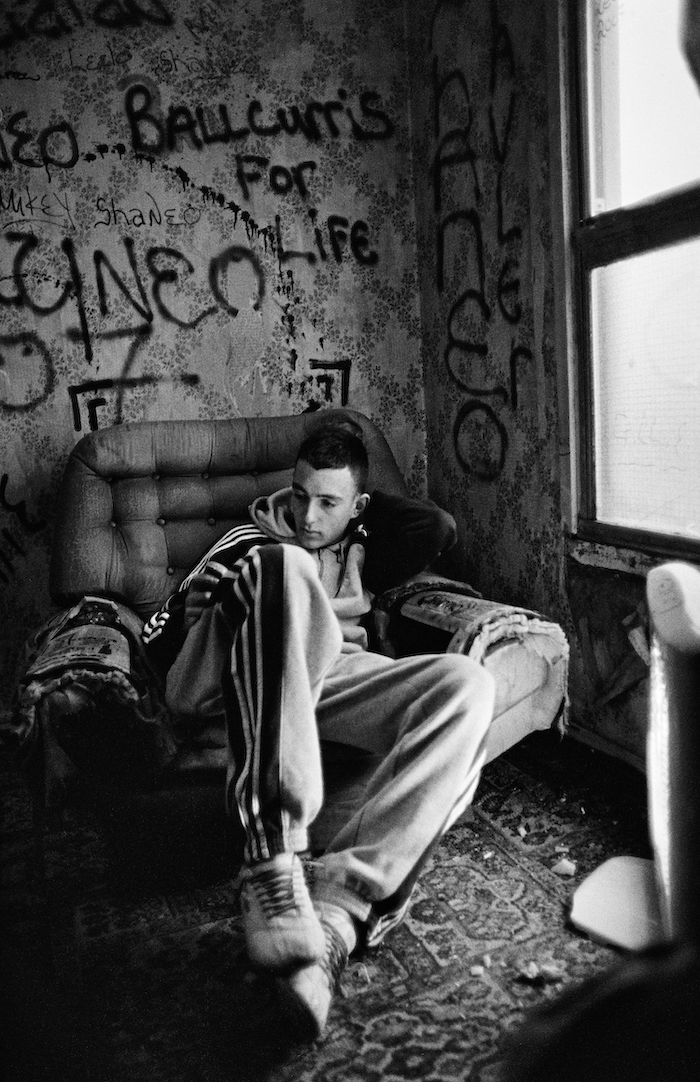

The photographs in Ross McDonnell’s book Joyrider are a coming-of-age story, one where everything and everyone are constantly changing in the midst of a world where nothing ever seems to change. Flipping back and forth through sequences of smoldering cars, drug-dealing tedium, thrills, and occasionally, their consequences, we witness an upside-down Neverland where unrealized childhood innocence rears in protest to the circumstances that prevented it. The premise and promise is to be forever unsure at what moment childhood ended and adulthood began. The world depicted is specific to a time and place, but the motivations that inspire the reactions are recognizable in the same youthful energy that shapes us all.

A cinematographer by trade, McDonnell began photographing young residents of the Ballymun housing estate in Dublin, Ireland, in 2006 after studying film at university. A failed government social experiment in the process of being torn down, Ballymun had become a symbol of Dublin’s underclass, ravaged, as the book explains, “by successive drug epidemics and inter-generational malaise.” Welcomed as a friend and documentarian of their lives on “The Block,” he tagged along on adventures, often entering hollowed out, vacant flats abandoned for demolition, watching as they reclaimed the space itself, as well as their own stories within. Some with children of their own, others barely grown themselves, the only future that seems certain is the fate of the concrete walls. “What’s really interesting with documentary work,” says McDonnell, “is seeing things change over time.” After photographing on and off at Ballymun for six years, it wasn’t until recently, almost a decade later, that time and perspective revealed this story of reclamation, as well as the larger context of the abandoned environment and the surrounding crisis. “Looking back,” he reflects,” I was also coming of age as a photographer, you know. There was a kind of symbiosis to what we were doing. You’re very energetic when you’re a young photographer. You experiment with your visual languages in a way that, the more you refine that craft, maybe the less you do.”

Since razed and replaced, Ballymun, as McDonnell captured it, exists only in memory, but within those remembrances are moments imprinted on film, free to be reflected upon, wrestled with, interpreted, and framed with meaning. Such analysis, however, always remains separate from actually making pictures. “The very act of photographing,” says McDonnell, “is about being present and very alive in the moment. Looking to the past or future doesn’t serve the photographer.” What we see within the Joyrider images is the present, briefly unencumbered by the branded stamp of the past or fearful uncertainty about the future. What makes photography so dynamic is that it captures the now, as well as being a fluid document of the past. “It’s really such an interesting way of being in the world,” affirms McDonnell, “to be able to express your curiosity so instantly. You just have to be there, you know, in the moment as much as you can, and I think photography is a great tool for bringing you back to that.” —Alex Nicholson

This piece was originally published in our Spring 2022 Quarterly.