Troy Lamarr Chew II is a precious gem who fittingly paints symbolic glints and sparkling jewels. He won the prestigious Tournesol Award and residency at San Francisco’s Headlands Center for the Arts in 2020, and when the studios temporarily closed, Troy headed back to his LA studio to continue painting for two solo shows, both stunners.

Kristin Farr: Tell me about your show at Parker Gallery.

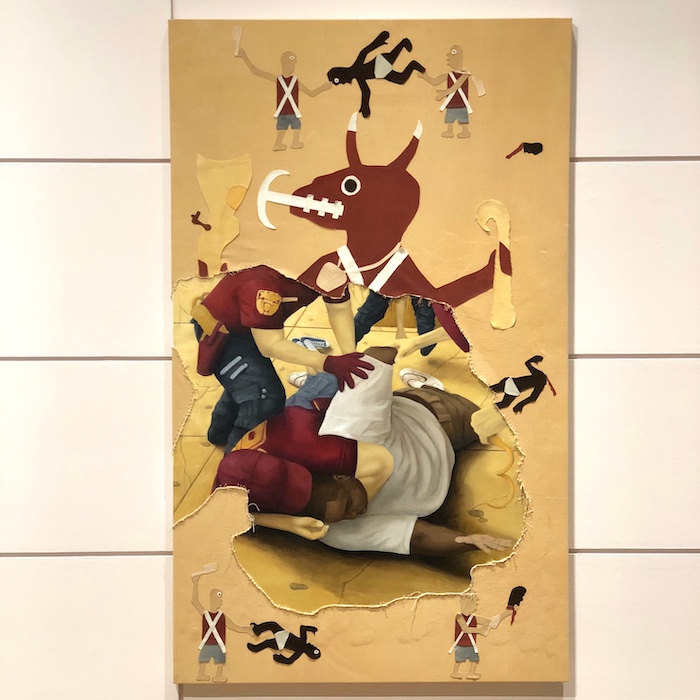

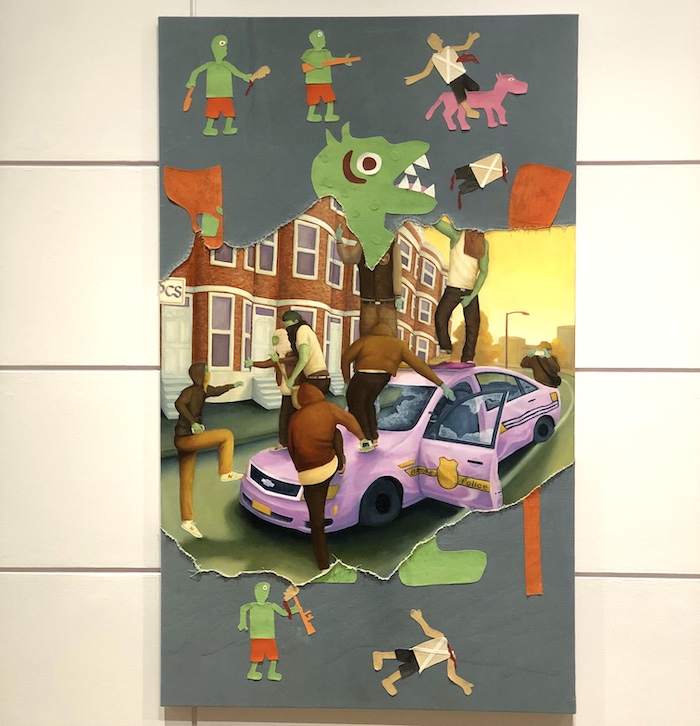

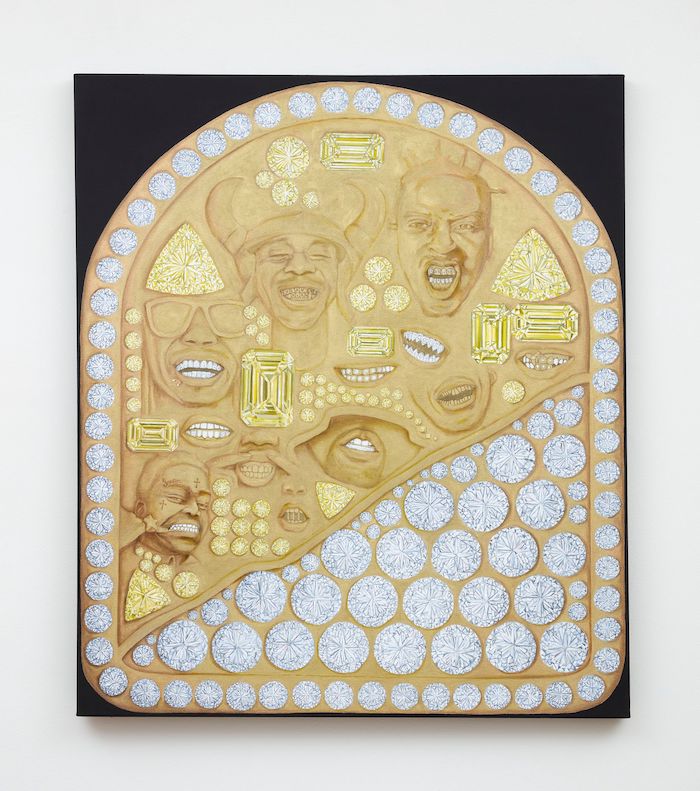

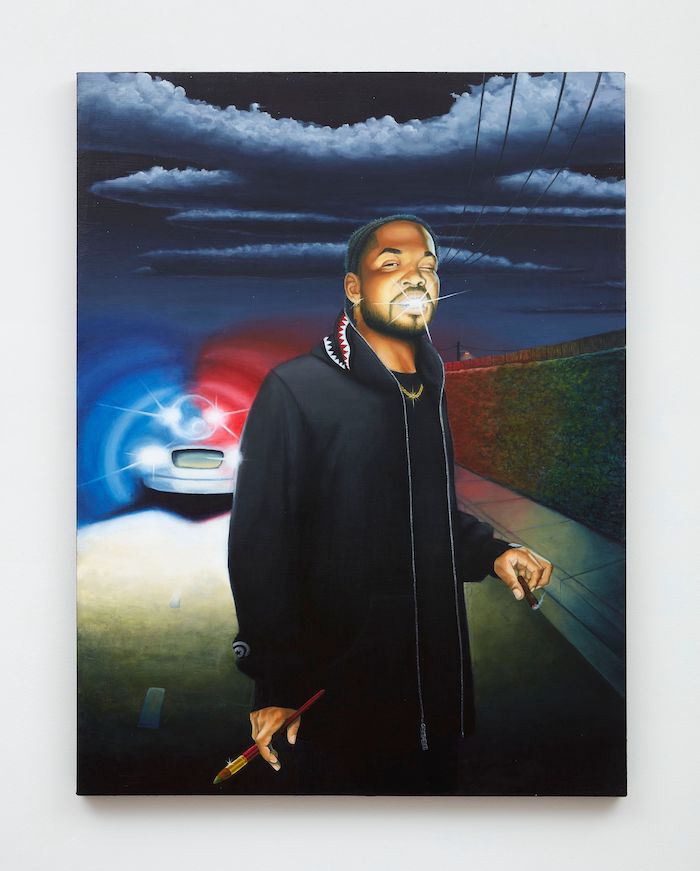

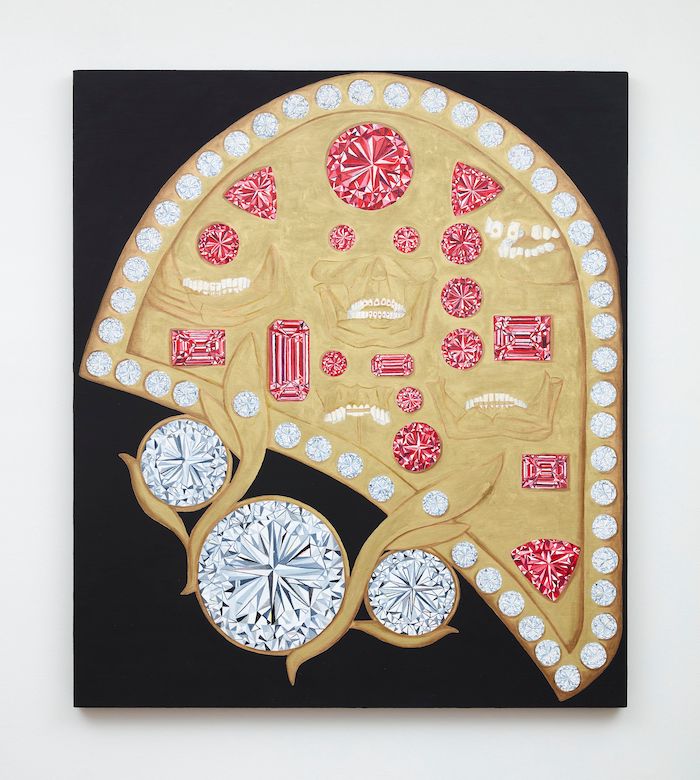

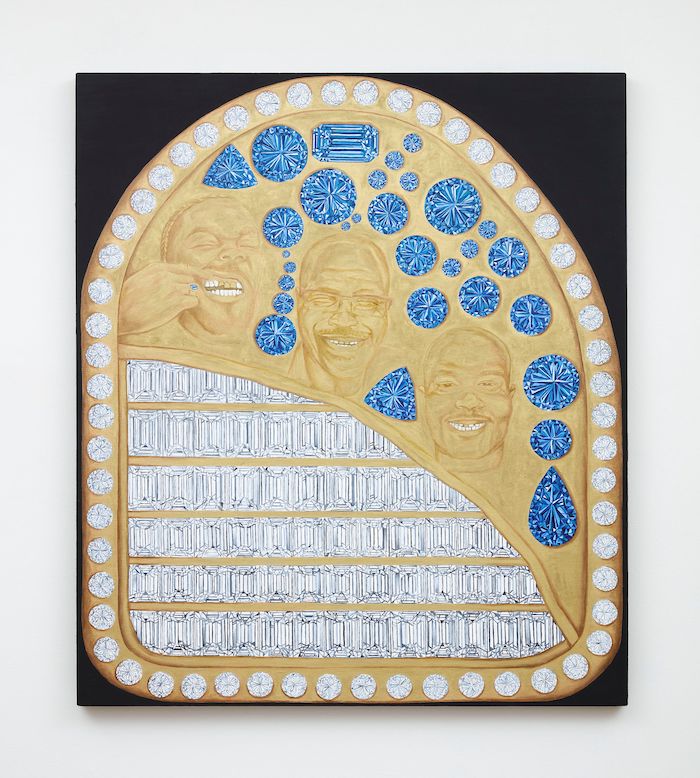

Troy Lamarr Chew II: It was titled Fuck the King’s Horses and All the King’s Men. It was inspired by an incident that happened the night I graduated from undergrad. I got beat by the police when I was walking home, and then thrown in jail. They knocked my teeth out, and I was trying to make a show remembering that. I made three paintings in the shape of a grill or a tooth, and each one commemorates the teeth I lost. I was thinking about the fragility of life, and teeth, specifically.

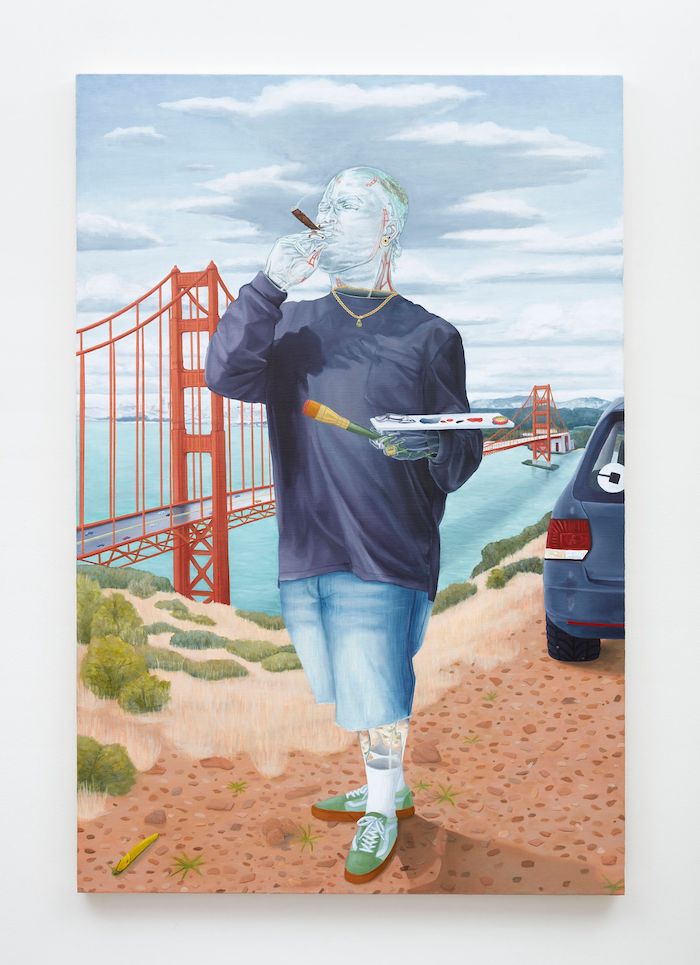

The glasslike self-portrait was made at The Headlands Center for the Arts, right when I had gotten the Tournesol Award. I was thinking about my place in San Francisco, as a black dude, and I was also Uber driving. It was this weird feeling of invisibility in several aspects of my life, so I wanted to recreate that in a painting.

I’m so sorry that happened to you with the police. You’ve said it was a catalyst.

Not to give them any praise, but it woke me up and showed me that I wasn’t living for anything. I was just going with the flow, drinking and going to parties because everyone was, versus thinking for myself and doing what I want. It was a big growing moment, if anything. It’s still a motivator, because, when I see my tooth in the mirror every day, it reminds me to stay in control. It was supposed to take away the shine inside of me, but it really brought it back out. With Fuck the Kings Horses and All the Kings Men, I wanted to make a metaphoric painting to show that the shine is still gonna keep going, whether you knocked my teeth out or not.

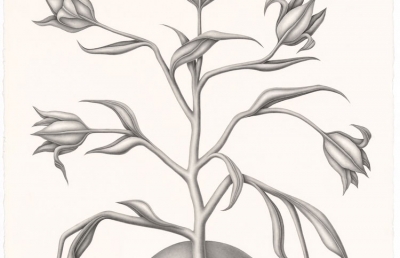

You paint light and reflections so well, with the gems, too. What’s the symbolism with jewels?

I was thinking a lot about how rappers with diamond or gold teeth use metaphors about how their words are pricey, or the words they say have a price tag.

It’s hard to vocalize, but also thinking about how my mouthpiece was damaged... putting stones and gold in there is my way of repairing it. That’s the only way to elevate broken teeth. It’s not a regular tooth, it’s gold, it’s a precious metal, so it elevates the tooth to a whole other level. But now that they were knocked out, I see their value even more. I have fake teeth, and I think about having porcelain in my mouth, versus my natural teeth often… but when I put gold in, it’s me choosing it, like a decision I made—not just the porcelain the dentist gave me by default.

Teeth are significant.

They’re used to identify people and all that. I was kinda thinking about that in the painting with the red stones. It has ancient skulls on it, linked to Mayan and Egyptian culture. They used stones to make their teeth beautiful, but the gold was typically a form of dentistry. Bridges were made with gold wire or gold plating to keep the teeth together.

I was looking at how “grillz” changed throughout time, and even within my own family. My dad has a false tooth in the front, my Granddad has two front false teeth... and they’re gold. Then I have three, so I’m looking at that lineage of the front teeth being replaced. But yeah, hopefully I’m the last one with these false teeth in my family.

Amen. I always thought it was interesting that the most common dream across all cultures is about losing teeth.

The teeth not being perfect, or the front of your face not being “presentable,” that is scary to people, especially when thinking about the pain. It makes me think of the tooth fairy or even Humpty Dumpty, and how he got cracked and nobody could fix him. All the king’s horses and all the king’s men tried to put him together again… But I feel there’s a line in that story that they’re not telling us. He didn’t just fall and nobody could fix him. That story had to be about fragility of life, or teeth at least. But that missing piece of the story reminds me of the police or authority figures covering something up and reporting it differently.

You paint figures in a lot of different ways.

I’m kind of a different painter with each series. There’s a series I have called Out The Mud, where I’m working with West African cloth. These cloths are usually understood from generation to generation within Afrian culture, and are typically passed down. But since I’m not a part of that culture anymore, I’m searching for that connection. I kind of let the cloth speak to me.

I recreate the clothes, then fill in the fabric with something that I think parallels black culture in America—just searching for the similarities and differences within the two cultures. I also don’t like to show the faces in the Out the Mud paintings because it’s more about the situation. I want the audience to fill it in—if you don’t know the situation, it could be anybody... it could be you.

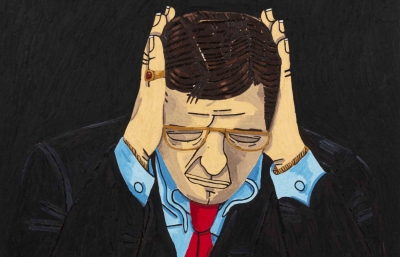

Tell me about the other self-portrait where you are more vaporous (seen below).

Invisible Man. I was thinking about the invisibility of being in the art world and in San Francisco. You could come to my shows and not even know I’m the artist. There’s been so many times where people talk to me like I’m anyone else at my show, and they might say the paintings are cool, and then after I say thank you, they’re like, “Oh, you did this?”

But then, I was an Uber Driver, and people would hop in, and ask if I’m Troy, then almost instantly put in their headphones. It was like I wasn’t being seen, but, I was, at the same time. That’s why I made it like a glass invisible man, something you can see, not totally invisible, but you can see through it if you choose to, or not.

You think a lot about words in your work.

Language is the biggest thing in my practice because it’s all a story to me. I’m trying to convey an idea to you, and I’m trying to get it off as clear as possible, even though I know everybody will have their own interpretations. I have an idea I’m trying to get across, and I do that through my visual language.

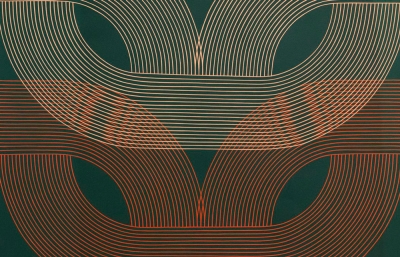

Your Slanguage paintings are like riddles with research.

It’s like when you listen to hip hop. Some lyrics go over your head, and you don’t know what they’re saying, but sometimes you do. Listening to more of that music, it can help explain itself, like context clues, but it goes deep sometimes.

I’m researching from the beginning of hip hop to now, so that’s almost 50 years worth of words. It’s a lot of music to listen to, but I feel like I have to do the research to learn, and that is listening to music.

Let’s talk about your latest show at Cult Exhibitions.

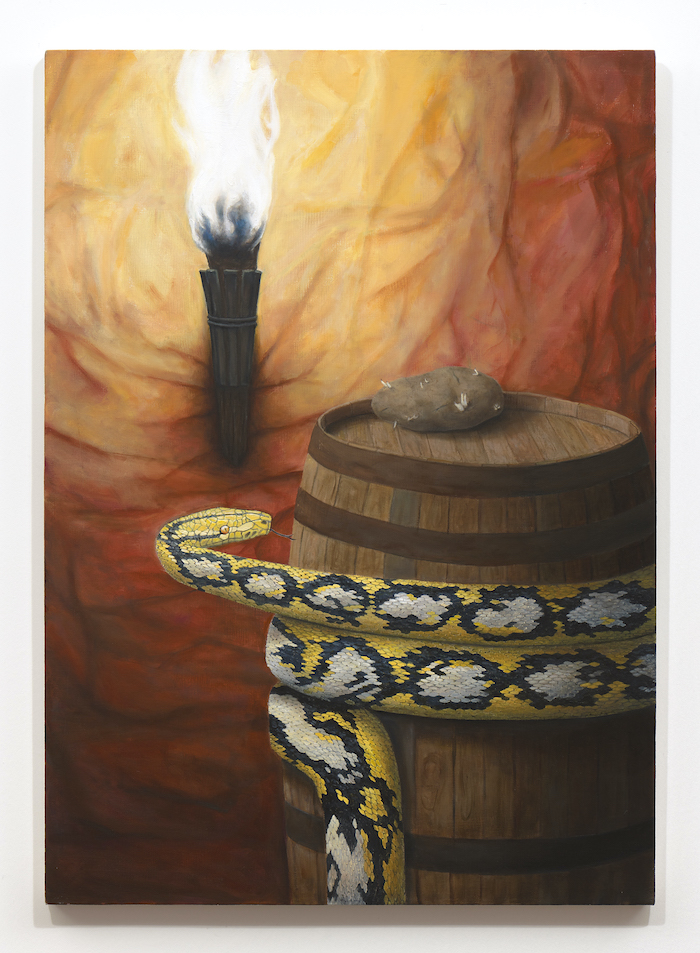

Yadadamean, that show was all about the slang created in the Bay Area, so it’s a lot of E-40, B-Legit, Mac Dre and Too Short references—all the words they created that are now popular within hip hop culture and American culture. I typically group the words based on topic, then put all the ones that relate into one painting—looking at it as a visual lexicon.

Cheese, bread, paper—all words for money created in the Bay Area. Weed references they made—crutch, broccoli, cauliflower, Girl Scout cookies… You hear them say it in the songs, but you gotta use them context clues to fill in the blanks, especially because some of that music was made 20-ish years ago.

There’s a lot of wordplay that was created right here in the Bay, and a popular weed company called Cookies comes out with different strains that are sweet-related, and that’s more slanguage that gets put into the culture, and into one of my paintings. Once a rapper says it in their songs, it’s everywhere. I listen back to who said things first; it’s a lot of hours of listening to music.

420, also coined in the Bay.

I have something in Yadadamean referencing that too.

What other cross-cultural connections stand out to you?

There’s a connection that Black people have to Africa that is obvious, but it also needs understanding. The way we dance, for instance, or even the way I paint, I see connections, because the traditional African cloths are also paintings. They were painted with natural materials from the Earth, just like oil paint comes from the Earth. The cloths are just like the paintings we look at that are worth millions of dollars. It’s all painted on cotton, it all comes from the Earth, both are the same thing, you know? That’s why I put them both on the same picture plane—now which one is worth more? I’m trying to bring them to the same level.

Troy’s latest solo show, Yadadamean, is on view at Cult Exhibitions through the end of 2020. His solo show at Parker Gallery was on view in September.

This interview was originally published in the Winter 2021 Quarterly