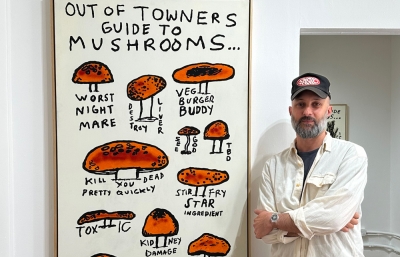

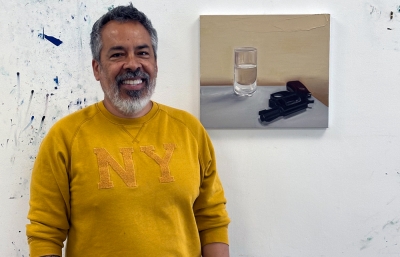

The way the world is strange, magical, and sad has never been lost on Pat Perry. The multi-hyphenate artist (painter, muralist, photographer, illustrator, storyteller, freight train tagger, and beyond!) has long cultivated a sense of wonder for scenes or situations that mainstream media outlets generally ignore. Though the treatment of his subjects differs based on the chosen medium, Perry tends to marry aesthetics with spaces that may never have been in touch otherwise.

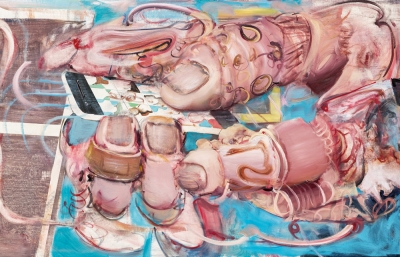

His solo show, Which World at Hashimoto Contemporary Los Angeles, is no exception: Tugging at the threads of the uncanny, otherworldly, and wondrous phenomenon that manifests in the typically ignored American midwest, the Detroit-based artist merges memory with images from crowd-sourced, public-facing archives like Craigslist or YouTube. Perry’s current painting practice “prompts us to consider which world we choose to live in based on which images we acknowledge and which we ignore.”

Before the exhibition’s opening, Perry answered some questions from Hashimoto Contemporary’s Katherine Hamilton about inspirations for this new body of work.

Katherine Hamilton: There was a sense of worldbuilding and storytelling in your last show with Hashimoto Contemporary, Sensemaking, whereas these new works in Which World pull more from reality (or at least somebody’s reality). Still, your artistic choices in depicting these scenes add a layer of imagination verging on fiction. Is there still a sense of storytelling in these works?

Pat Perry: I see these pictures inhabiting the same world as the artwork from Sensemaking but with several of the embellishments removed. I wanted to strip away the parts that felt essential then but don’t feel so crucial now. When I was making the artwork for Which World, I tried to imagine that, all together, the pictures are telling future people a story. Thinking about the paintings as artifacts for someone a long time from now allowed me to look at the objects and scenery through a whole different lens.

Many subjects in Which World are confronting you like someone not used to being documented: the Amish rollerbladers, the ghost at 7/11, the group bonfire in the swimming pool, and the goth teenager raising the banner behind the house. Throughout all the pictures, someone is enduring something.

The reference images you used to create the series of “Craigslist” paintings show objects lined up for sale. The images originally existed as utilitarian documents rather than aesthetic objects—these aren’t “picture perfect” images, per se. Similarly, your series of firework paintings are based on screen grabs of videos of amateur firework displays. They’re hazy like memories—the quick, wispy brush strokes erase the subjects’ specificity. What drew you to these vernacular images of people, places, and things as subjects for painting, a medium historically used to elevate its subject matter?

Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace are the places online that seem to most honestly lay bare what life is actually like: A lady that spelled couch wrong is giving away a “free cough” behind the Helena Trap Club; A man in Akron, Ohio is selling a 2010 Kawasaki Ultra 260x Jet Ski, “due to recent knee surgery”; A man’s 95-year old mother has decided to get cremated so he is selling her cemetery plot in Franklin Memorial Gardens.

Or, in some home video of fireworks on YouTube, this blind guy shoots off fireworks every year for his kids and neighbors, even though he can’t really see them. He only hears the noise of the explosions and everyone laughing. That is actual life. A lot of what makes this world interesting comes from people living unhistoric lives who will never have their own Wikipedia page. There’s a lot in that deserving of elevation, or at least worthy of making paintings about.

Part of your impetus for creating these paintings was to locate the sublime in moments where the digital age is forced to meet mundane, everyday life. What do you find interesting about the convergence of these two specific worlds?

Media is usually presented to us with the boring parts cut out, leaving this skewed version of what we expect reality to be like. Social media and online life aren’t especially helpful in dealing with what most of life is actually like. The artists who leave me totally in awe are the ones who take things to a dimension—focus on something—that everyone else blazed right by. When you see that disregarded thing, it almost seems obvious, and you wonder how you overlooked it. I’m thinking of what John Prine wrote songs about, or the first time I watched Burner Phone by Jim Swill.

To be sure, I made these pictures to touch on this moment in time: the age of screen time, isolation, distrust, Great Power Competition, and the attention economy. Mostly, though, I wanted the paintings to focus on the timeless parts: the ageless predicaments and conditions we find ourselves living through. For the pictures to somehow say, “yes this is a unique moment, but the human story, in many ways, is the same.” We are reliving new versions of old stories.

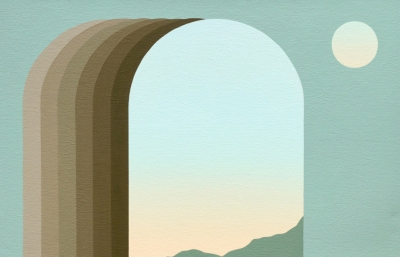

Large, sweeping, chromatic landscapes also make up a portion of the over thirty works in Which World. We’ve seen elements of landscapes from you before—wheat fields, white houses obscured by pine trees, abandoned and defaced televisions on the side of the river—but this body of work seems to privilege the genre, giving it more literal space on the canvas. Can you expand on your interest in landscapes?

I think scenery makes you consider the passage of time. The experience of being here and conscious is overwhelming in itself: getting to be in the world, getting to be in this rich country with problems, getting to be on this interstate or out in this field somewhere. Landscapes stretch out time: pictures of them are historical because they are relatable and universal in some fundamental way related to time. I’m not sure why, but everyone has had that moment of being somewhere, just looking at that.

Above ground pools say a lot. They're a compromise: seemingly innocuous and mostly similar, but what’s around them changes, and also the viewer changes. They’re a status symbol, but the status the pool represents more about the position of the viewer than the pool in itself.

Right, like how you perceive an above-ground pool might reveal your ideas on class or class aesthetics to yourself if you just think it and to others if you say it out loud.

I also can’t help but feel a little miffed that David Hockney stuck to in-ground California pools. The above-ground pools deserved some remuneration.

These works have an element of uncanniness or even otherworldly-ness, including religious and ritualistic imagery such as the Virgin Mary, Nativity Scenes, or Amish rollerblading. Have you had any specific spooky encounters that influenced some of these paintings?

Being in the world is a supernatural encounter. If I go for a walk, I may feel like I’m taking everything in, but I’m only registering a narrow piece of reality. I’m equipped with an outdated primordial thinking machine—mainly programmed to survive and find food. I’m going for a walk in 2023, though: Rosemary and I are traipsing for miles down the shoulder of a six-lane road by a Lowe’s and a Cold Stone Creamery. Half the road is being torn up by beeping construction machines. I’m also checking Google Maps to see if O’Reilly’s is open yet, because it’s 7 am, and the fuel pump on Rose’s 2001 Toyota 4Runner just shit the bed on i90 in Minnesota. We talk about an article we read together yesterday about the discovery of the Higgs Boson at CERN. Some geese fly over. We are walking past an old mall with tinted skylights above the entryways. We have some time to kill, so we cross a tremendously large, empty parking lot and enter.

It turns out that the mall is almost completely empty except for the carpeting and benches. Every store is closed except for a cell phone store. It’s a one-story mall made up of octagon-shaped areas connected by hallways. We almost turn back, but when the food court comes into view in the back of this mall maze, lo and behold, a herd of thirty or so senior citizens congregate. They are wearing pastels and white shoes (all ladies and one patient husband quietly reading a magazine in the corner). They are erupting in laughter at three folding tables, pushed together, in this mall with all the lights dimmed. They turn to us and offer us fritters and coffee. (It’s the watered-down kind of coffee that’s more like tea.) We sit with them and briefly join their ritual.

Yeah—there’s spooky magic in the world. There’s also an awful discomfort from the unanswerableness of it all. It must, at least partially, explain why groups of people, across all of time, have found meaning in religious traditions, astrology, or some other monocausal idea. If there is a silver lining to overwhelming incomprehensibility, it’s that if you pay attention, you get to feel mystified by tiny details.

The works in Which World seem to expand on some ideas you brought up in your essay “Two Guidebooks and a Painting,” published by Juxtapoz in 2021. You recount how you had lived in two ideologically separate worlds, which also came with their own form of visual language, symbols, and signaling. Can you say more about occupying the space between worlds (one real and flawed, another idealistic and utopic) as an artist and a regular person?

As an artist, maybe the best way to make a new and better world is by simply trying to make this world a little better: to plumb the depths of this world and to lessen suffering a little in it. This art project was about growing sensitivity for this world, the one right in front of us. I try my best to approach picture-making in a way I wish I saw more often. Art is there to recomplicate the world and remind us—sometimes forcefully—of all the simultaneity.

As a regular person, I think about how tragic events find you more frequently the longer you are alive. They shift you, and you enter into new stages of moral development. There is a frailty and sadness in the nature of things, and it transforms from being conceptual to being scary and real. I recently lost a close friend who was also a painter, who I hope would’ve loved these new paintings. I think that when tragic things happen, sometimes they unlock a tenderness that helps navigate multiple ideological worlds. These events make you nicer. You remember that everyone is in a battle. Everyone misses someone.

Maybe the request here is for more practical advice about navigating multiple worlds. Here it is: If I’m in a new conversation with someone whose disposition I’m unsure of, I just start talking about trees. Almost everybody has a tree they like. Maybe ask, “Do you ever really stop and notice them?” or, “Do you know if Aspens can grow this far north?” or “I wonder how long those trees over there will be there for... probably a long time.” As an artist and a regular person, that’s my advice: consider trees with others.

Pat Perry’s solo show Which World is on view at Hashimoto Contemporary Los Angeles through November 4th. Opening and installation images were taken by Megan Cerminaro.