In a time when the unofficial remix version of a song can outshine the original, the same can hold true in the world of fine art. Such is the case for an artist named Madsaki. He has wrestled himself right up in the grill of some of the most cherished painters in history, the masters who have been studied by generations of art students. Taught to observe and mimic a virtuoso’s every stroke, what happens when the student takes on the master? What happens when the student takes on many masters?

Madsaki’s spray paint, vandalistic version of the master’s original work is just that. Does it suck or make the original art even better, or possibly worse? What Madsaki is doing, at least for me, is helping me appreciate both versions for what they are. Art. He has a modern take on modernism. His impression of impressionism is impressive, and his expressionism is exactly that—expressive. In fact, he can flip any “ism” because he is attacking the giant with a thousand cuts versus one major blow. This is how Madsaki keeps the art world on its toes, so watch out—you may be next.

Read this feature and more in the December 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine.

Joey Garfield: They say imitation is the best form of flattery, but what the fuck are you doing?

Madsaki: [Laughs] I guess this is who I am. You know me. I do stupid things with seriousness. I love and respect art but at the same time, I like fucking shit up. You know when you’re wasted or high, you come up with stupid funny ideas but the next day, you wake up, and you’re like “Nahhh.” But me, I just do it. I get a kick out of it. I guess I don’t care what people say or think. If I’m having fun, it’s good. That’s what matters.

Word. So, you were born in Japan and live there now, but where did you grow up?

I went to the States in August of 1980. I was six. On the way home from JFK, I remember seeing cars and tires burning on the Van Wyck Expressway and the subway trains colorfully bombed with graffiti. But as soon as we crossed the George Washington Bridge into New Jersey, the landscape changed. My first impression was, “Wow, the trees are big and they’re all over the place!” I lived in Ridgefield Park and then Leonia, New Jersey.

Did you like it or hate it there?

It was confusing. Everyone had yellow or golden hair and looked the same. I was Japanese, and at that time, there were almost no Asians living there. I thought I could ride my bike back to Japan. My dad brought our radio from Japan and I turned it on, thinking it would still speak Japanese [laughs]. You know, Leonia was a typical white, middle-class suburb. When I was living in Ridgefield Park, I got rocks thrown at me almost every day walking around in the neighborhood. Those people would call me “Pearl Harbor.” I spoke no English at that time, so I thought it was my American name or something. But one day, I was getting rocks thrown at me and some kids in my class saw. They came over to me and taught me this magic word called “Fuck you.” My life literally changed after that. But even though I was Japanese, I grew up doing the same things as what everyone did back in the day: riding BMX bikes, playing football, watching MTV and soft porn on Cinemax. By the time I was ten years old, I was headbanging to Metallica and talking like Eddie Murphy. I’m basically white on the inside.

Like a Twinkie.

Yeah that’s me [laughs].

Portrait by Joey Garfield

What gravitated you towards art?

I spoke no English. The only way to communicate was through drawing. I think that’s one of the reasons that got me doing art. I drew something, and kids would teach me the English words that went with my drawing, and I ended up walking around the entire school showing my drawings all day because sitting in class was meaningless. There was no such thing as ESL back then, and I was the only foreigner in school. So the school had to ask some student to voluntarily teach me English for an hour every day. I loved it because this sexy blond girl with a comb brush in her back jeans pocket would teach me. I would draw something and then write the words for it. Every time I got it right, she would kiss me on my cheek. It was inspiring. By high school, I was fluent, but shit just changed. I was, like, “Get me out of this place!” I was tripping on acid every day and smoking weed.

Every day?

Yeah. Every day. You have to understand my town was full of Guidos... it was hopeless. The boring New Jersey life inspired me to do drugs. The drugs inspired me to do art. Senior year of high school, my parents were like, “Now you have to go back to Japan and begin working on a salary track,” and I was like, “Nuh uh. I need to go to art school.”

Is that where you learned about all these masters of the classic arts?

Yeah. I know all the classics. I had to take four years of art history at Parsons. I got traumatized in art school.

Really? How?

I can’t paint. I’m a lousy painter. I never was able to control the brushes like everyone else. It was a pain in the ass.

How’d you get through four years of art school without being good with a brush?

The wrong guy went to the wrong school! I remember, in freshman year, professors saying, "If you’re lucky, maybe one or two of you will graduate and make it in the art world, so if you don't want to waste your money, quit now." I did graduate from Parsons, but afterwards, I wasn’t doing art at all. To tell you the truth, I was mad lost in life I didn’t know what to do with myself. But meeting The Barnstormers changed everything in a millisecond. See, the Friday before 9/11, I got hit by a car that blew a red light on Delancey and Allen Street in Manhattan while I was messengering. My bike got wrecked, so I was just sitting at home doing nothing. Then, right after 9/11, a phone call came out of nowhere. It was from Mike (Ming) saying his crew called Barnstormers were painting in Brooklyn, and he told me to come over. I had been messengering for three years. I wasn’t doing art at all, so I didn’t feel like going. I hated art at that time but was bored out of my mind, so I went just for the hell of it. Glad I did, bro, it blew my mind. I was like “What?! I didn’t learn any of this in art school.”

That was the Smack Mellon show in DUMBO in that huge warehouse space where everyone was painting on the walls and filming the stop motion paintings on the floor.

Yeah, and remember there were chickens running around the place? It’s amazing how one experience can change your whole life. It woke me up. It was like getting slapped in my face by Jesus or something. Everyone had their own style and identity, and their pieces were top notch. I said to myself, “Fuck being a messenger. I need to start painting again.” This is exactly what I was looking for in my life. To this day, honestly, I still don’t know why I’m in the crew. I sucked at painting and I was like a bus driver for The Barnstormers.

Juxtapoz x Superflat mural at Vancouver Art Gallery

It changed all of us.

The younger generations in Japan still come up to me and say Barnstormers changed their life. They love hearing stories about the crew and what we did back then. It was enlightening and that’s why I’m here right now.

What made you go back to Japan?

My visa was up and I was going to be deported. I left with 200 dollars in my pocket. Coming back to Japan was even weirder than leaving because I look Japanese and speak fluent English. I mean, I am Japanese. But when I got here and started speaking Japanese to people, it was off. I couldn’t communicate. It was a mess.

It’s like you were an outsider all over again. You were making abstract geometric shapes over there for a minute, so what happened to those? What you are doing now is very far from that.

After that geometric shape phase, I got lost and started doing weird things, and while I was doing the weird things, the text thing popped up from nowhere and then the Wannabie’s came. I’m feelin’ it behind my balls. I’ll be doing this for years.

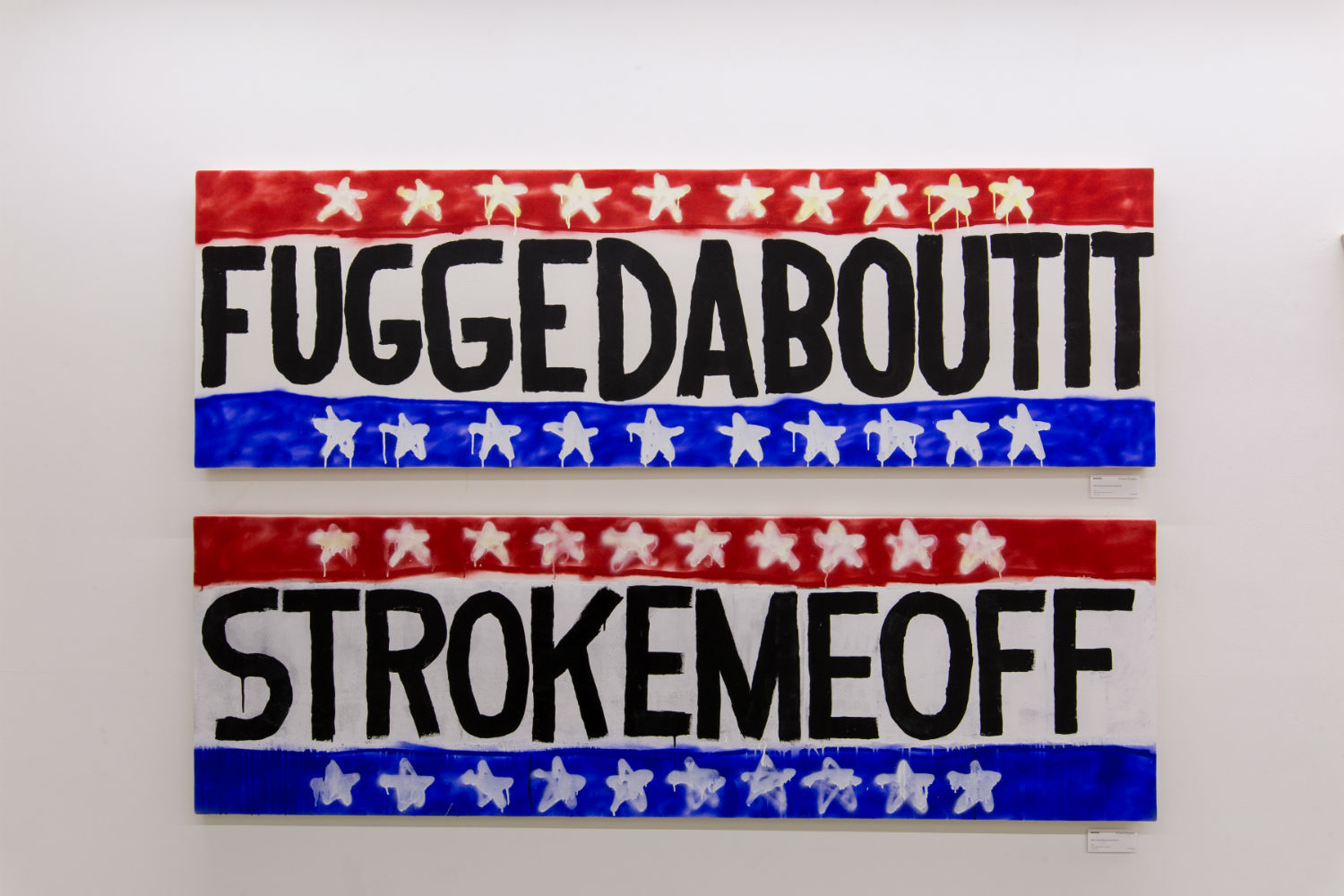

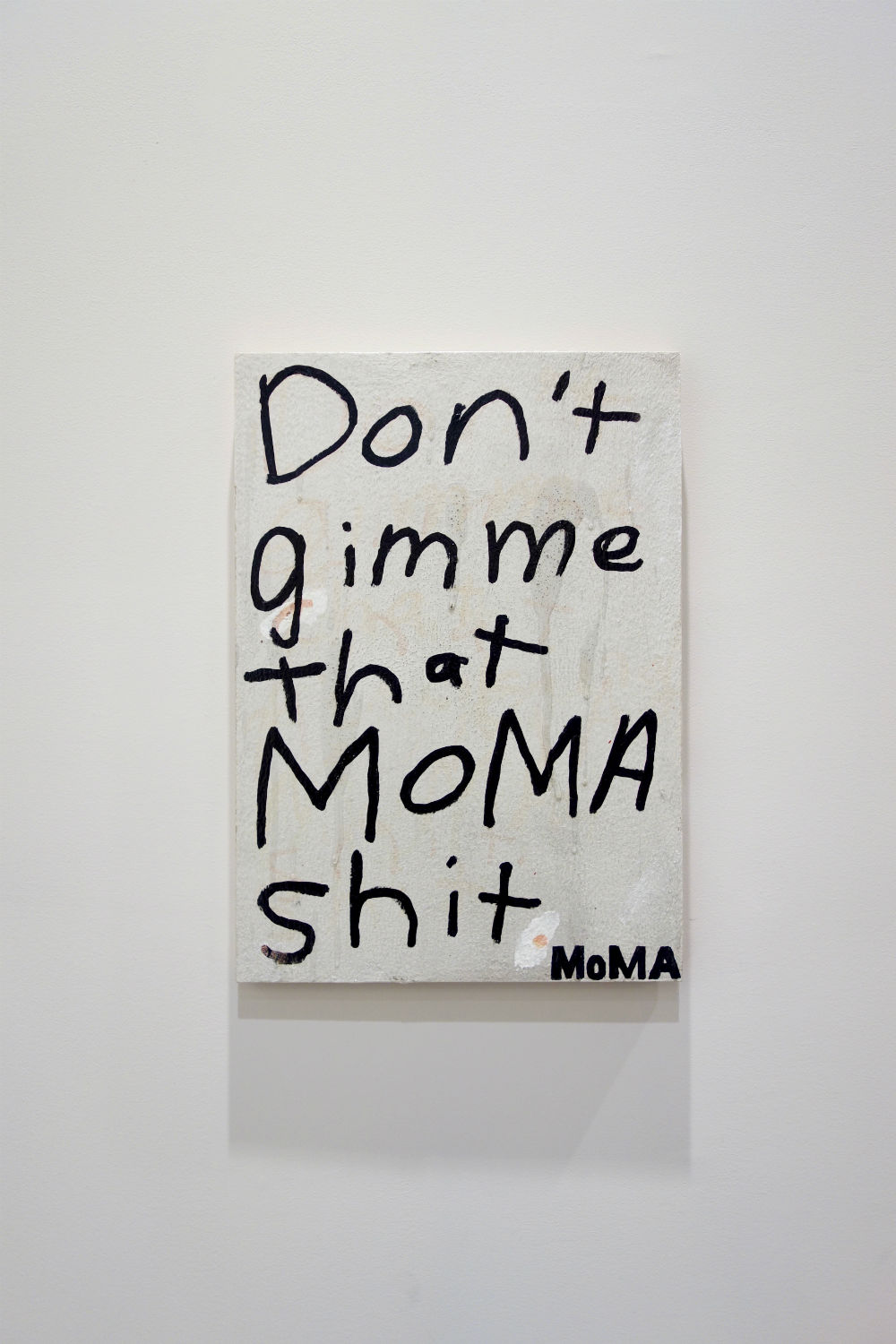

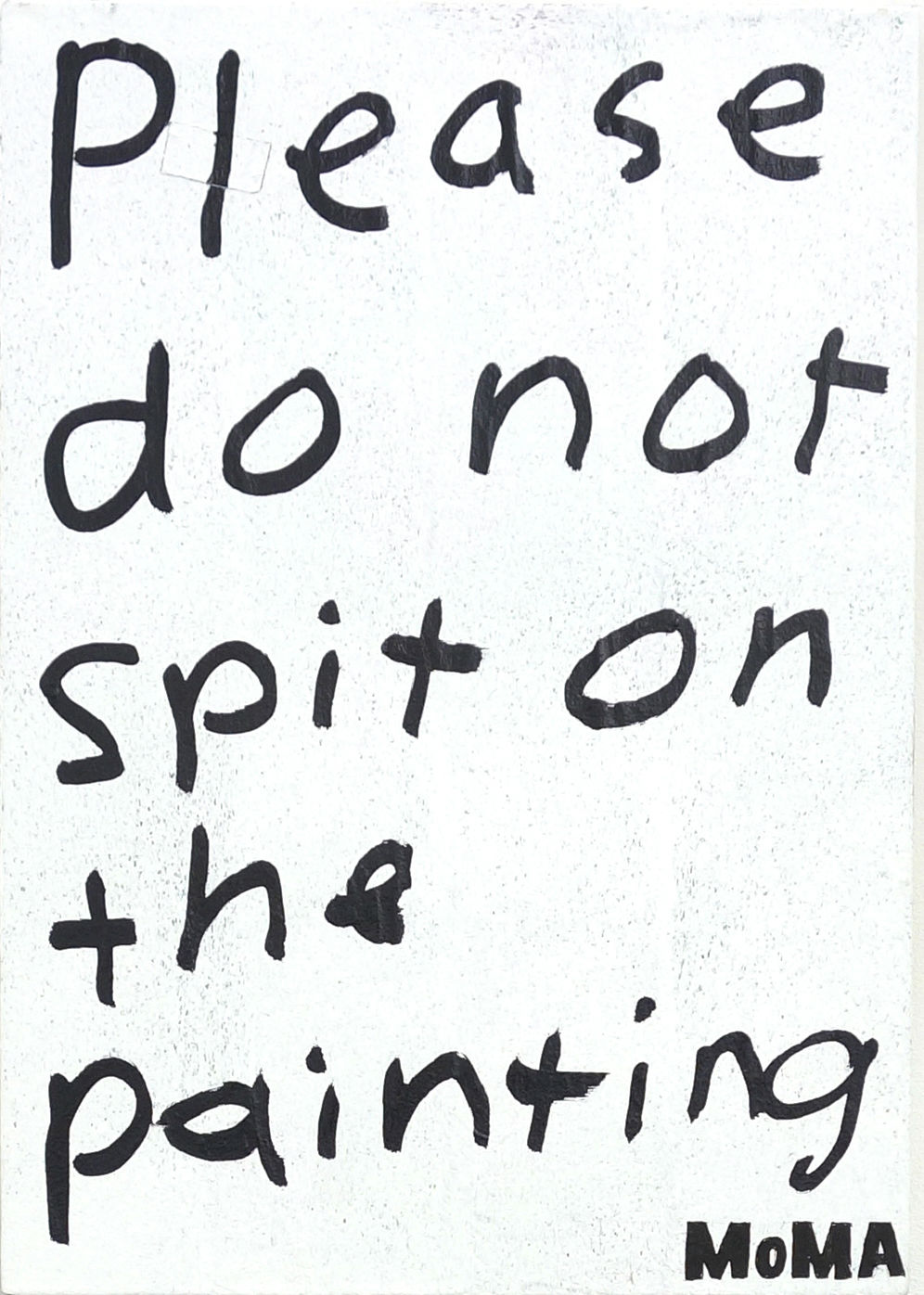

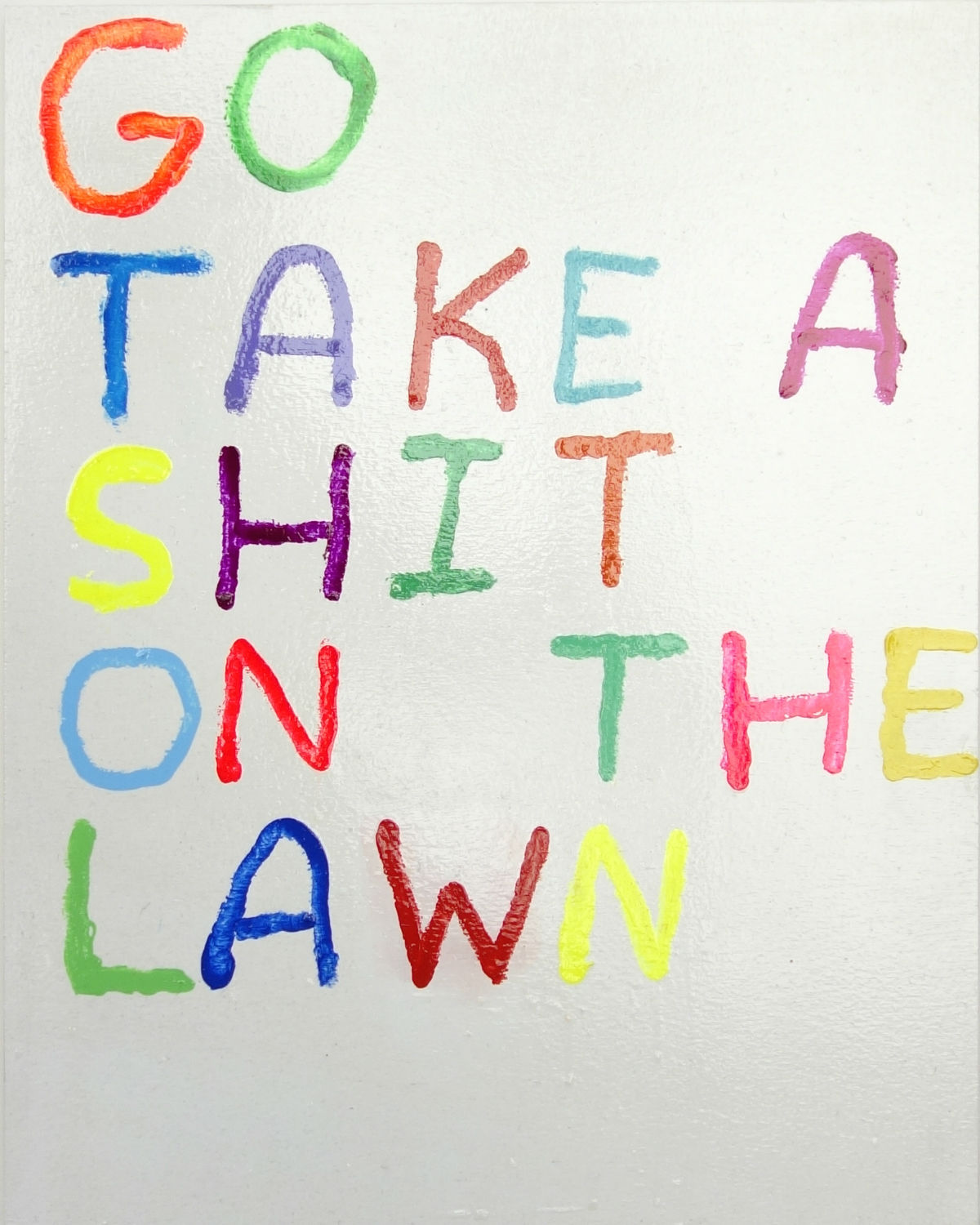

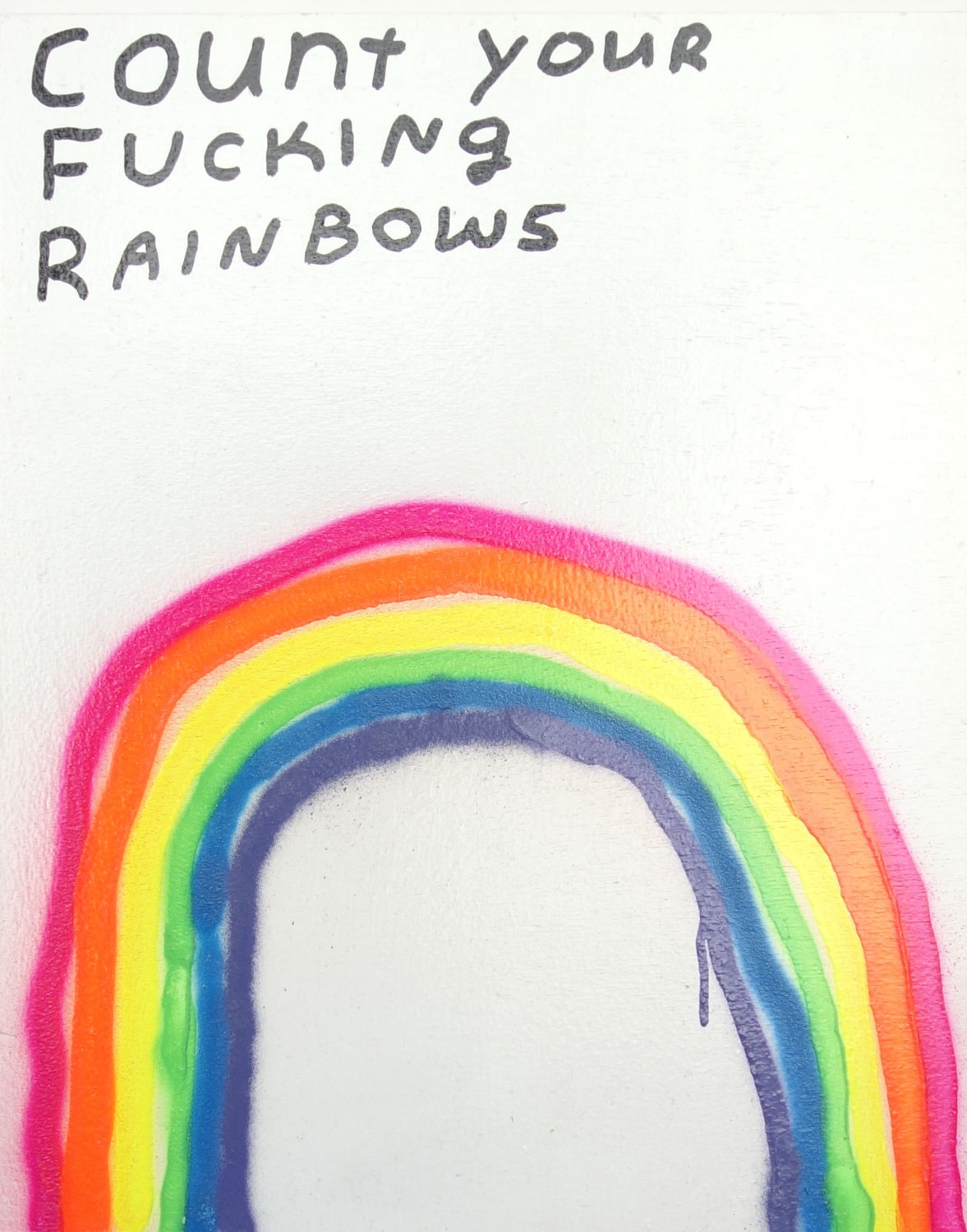

What’s up with the text paintings? They are like blurts ranging from nasty, to naughty, to philosophy. How did those come about?

Since I can’t speak English in Japan, I have to talk to myself, so I have these conversations in my head with, like, an imaginary friend. That’s how those phrases come up. When I got lost painting around 2012, I was intimidated by the empty canvas, so I would write some of those phrases on it to relax myself before painting. But one day, when I wrote “Holy Fucking Shit” on the canvas, I was like, “This is it!” I wasn’t sure if it was art or not, but my guts told me to keep doing it. And I did. I made, like, 60 of them and told my friends before they were exhibited, “If I don’t make it, I’m going to quit being an artist.” But they almost sold out! So I kept at it. Japanese people didn’t even know what I was writing; it just looked cool. They bought ones like DickSlap or Ghetto Ass Shit.

What are the rules of making those?

It just has to be really bad and I have to be able to laugh at it. If there is any doubt or confusion in the phrase I won’t do it. One hundred percent pure stupidity—then it’s good.

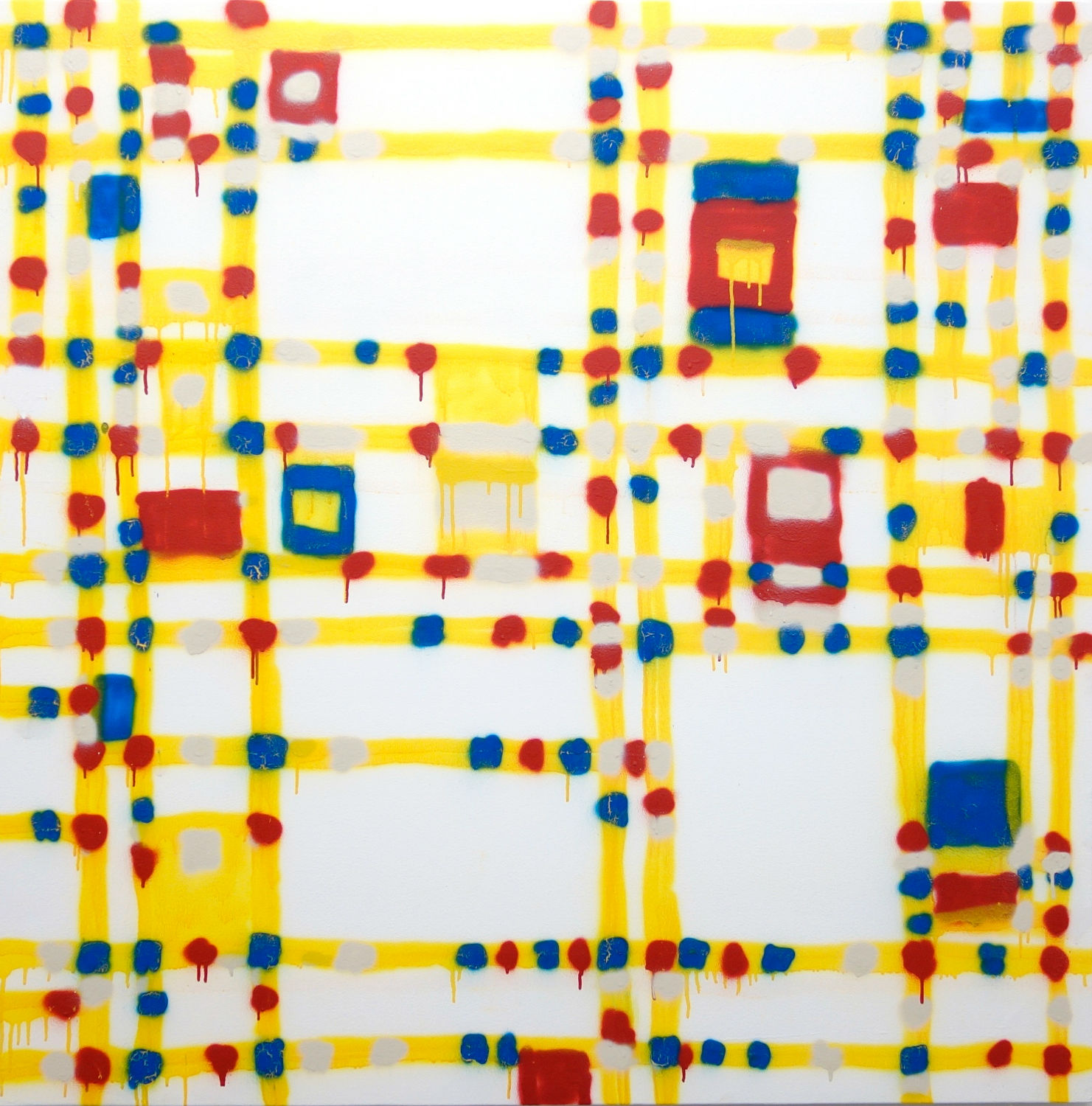

How did you transition to painting versions of the classics, and what are Wannabie’s?

Wannabie’s is made up from “wanting to be” plus Christie’s plus Sotheby’s. It’s my comment on pushed-up nose art, high society buying paintings just to brag about it type stuff. That’s what they all are. I’m against it and in it at the same time. I had been doing the text paintings for two to three years, and my behind-the-scenes guy, Taku, from Clear Edition & Gallery told me that next time, I should do the same concept as the text paintings but paint images along with the text. I was like, “Uh-oh, I have to paint again.” I thought about it for months and the answer came.

What was the answer?

Ok, so I had to figure out what the painting version of the text pieces was. Say like the Holy Fucking Shit piece. That is an everyday phrase we use. It is a part of society and culture. So what is the equal to that in painting? A phrase we all use is the same as the painting that we all know. So “Fuck You” and Matisse is the same thing. Everybody knows Matisse and everybody knows “Fuck You”; it’s on the same level. Then I figured out a way to paint the images with a similar attitude and humor that the text paintings had. When I find the image that I want to paint, I search for the dimensions of the painting. The size or the ratio has to be perfectly exact as the original for me. The interesting part is, even though I make the frames and stretch the canvas, when I paint, I don’t even touch the surface since I use only spray cans. I started using spray paint for a change with the text paintings and fell in love with it, especially the smell. I don’t even use them correctly [laughs], but I was able to do what I wanted to do in seconds.

What makes something Wannabie worthy?

I can’t make a copy of something that no one knows. So the image has to come up on Google’s first page or at least within five pages.

So it has to be like a number one hit song that everyone knows the words to.

Yeah. For instance, if I type “Henri Matisse” in Google images, I’ll do the one that everyone sees and knows.

Has painting all these classics changed your idea about the artist who did the original for better or worse? Like Renoir?

Renoir? I fucking hate Renoir [laughs]. I hate his paintings so that’s why I had to do it.

He is considered a master.

Yes. But when you say “art” in Japan, the older generation thinks of that Renoir as art and only that. It’s easier for them to understand, so I had to do my version of Renoir. I do respect them all. If I don’t, I can’t do it. You learn so much from their techniques, from colors to composition, the history behind it all. But it’s all useless to me because I just go to the next artist. I don't need to do what they have done. They've done it already for you.

In the time since we started working on this article, you’ve linked up with Takashi Murakami. How did that happen?

Last September, I saw on Instagram that he was following me. I thought it was an accident, like he pressed it when he was taking a shit or something, but he started to like my stuff. A month later, I finish my Matisse Music piece. I posted it and Murakami says he wanted to buy it. I was like “Fuuuuuuuck.” It’s in his collection! And from there we started hanging out.

Did you start making your versions of Murakami’s artwork before you met him?

I always wanted to copy his paintings but never had the guts. But he came to me and said “Madsaki, can you copy my flower painting?” I was like, “Yes. I was waiting for this day.”

Another thing that’s happened since we started talking is that you’re doing actual collaborations with him.

At his office party, he asked if I could paint with him, and I said, “Of course, but I’ll do the background and you do the rest.” I painted the words “Fat Man” and “Little Boy” on there. They are the names of the atomic bombs that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which everyone in Japan knows. Then I painted “The Fat Man Paid” and “Little Boy Blew,” and he was like, “What does that mean?”

Are you going to continue copying the classics?

If I keep on doing the Wannabie style, everyone is going to think I’m just the Wannabie painter. Sometimes you have to do something crazy and that’s that. But you have to do something original. After the Murakami show at his Hidari Zingaro a few months back, he said he wanted to have me join the Juxtapoz show in Vancouver. I asked, “What do you want? A classic or maybe a text painting?” He didn’t answer me. But the next day, I get an email from him saying, “Paint yourself fucking your wife!” as a joke. I was like, “Whaaaaat!” So I’m gonna do something like that. It’s in less than two weeks.

Well, you better get busy, if you know what I mean. Last question: where did the other half of your name go?

It was too long and it sounded too much like “Chia-pet.”

Madsaki will be featured in Juxtapoz x Superflat at Vancouver Art Gallery, November 5, 2016—February 5, 2017.

----

Originally published in the December 2016 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine, on newsstands worldwide and in our web store.