Robert Rauschenberg

Scamp Artist

Interview by Gwynned Vitello // Portrait by Dennis Hopper

Robert Rauschenberg was a scamp artist, and I mean that in the most exuberant sense of the word. He saw beauty in the ordinary, envisioning the most humble object in another medium, bestowing it with new life and a fresh perspective for the viewer. In the Combines, he was one of the first to pair painting and sculpture, kitsch and culture. For him, art was life, and his White Paintings became complete only through the eyes of the audience. The dynamics of dance, maybe the ultimate expression of joy, guided his relationships with friends, animals and the environment, a harvest that is still being shared at SFMOMA’s new exhibition.

Gwynned Vitello: When I hear Port Arthur, Texas, I immediately think of Janis Joplin, who shares the same birthplace as Rauschenberg. Did they ever meet?

Sarah Roberts: It meant something to him that they were both from Port Arthur. They’d both made it out, and her death was important to him, a loss that he mourned. She wasn’t just a passing acquaintance.

This could take the whole interview, but how did Port Arthur, Texas, spawn Robert Rauschenberg, one of the most radical artists of his time?

He was born into a pretty conservative, religious family, and was raised in the church. He even had a period where he thought he would go on to have a career there—until he realized that his church prohibited dancing, which was one of his favorite things to do. As a result, he then decided he needed a new career path.

I think he had a really tough time in high school. He was very much affected by dyslexia, and as he put it at the time, called himself stupid and felt like he could never excel in academics. His mother was a seamstress, mostly as a hobby, and he would sew with her and make art, but never really had in mind that he would be an artist. He went to the University of Texas very briefly to study pharmacology, but refused to dissect a frog and left the program. He had grown up around many animals and had an affinity for them.

He also spent time in the army where he was stationed in Southern California, and it was there that he found himself at the Huntington Library, when he had a moment of clarity after seeing Blueboy cards.

As a child, he had a collection of Blueboy playing cards, and the reconnection with these cards sparked something in him. He realized that someone actually made these cards, that they were important, and in turn, valued by other people, and most importantly, that people could make a living in art, and that possibly, he could too. He then bounced around through a couple of art schools in Kansas City and New York before making his way to Paris, as so many did after WWII. It was there that he met Susan Weil, whom he would marry shortly thereafter. She was a little more savvy about the art world, and at that time, an article came out about an institution called Black Mountain College which was this very progressive, experimental art program. They soon decided to go together.

This is really when he came into his own. He had already been practicing and studying art for a few years, but really it was getting to Black Mountain where he found the courage to follow his own voice and get some very foundational education from Josef Albers, the great early twentieth-century teacher. What worked well for Rauschenberg at Black Mountain were their sort of rigid fundamentals. There is a kind of skeleton under a lot of his art that shows a deep understanding of color, structure and composition. But then there was this flip side, which was this eagerness to experiment radically, to work with other artists and to work in an interdisciplinary way. He took not just visual arts, but dance, voice, Russian, and textile construction (from Annie Albers). They were looking at the arts broadly and thinking about how all those things resonated with each of them. The right people at the right place came together at the right time. The roster of people who attended Black Mountain in the late ’40s and early ’50s is unbelievable, and key figures for Rauschenberg were Albers, Merce Cunningham, Jack Tworkov, Cy Twombly and John Cage, who all became part of his inner circle.

Did he ever speak about dyslexia playing a positive role, and do you think it somehow opened him up to dance and creating a comfortable space?

He spoke of it later in life, though I’m not sure at what point he connected the dots and thought to himself, “Okay, that’s what’s going on with me!” There’s a school in Washington, D.C. primarily for dyslexic students that he supported. He himself really didn’t read too much. Even though he was able to, he found it quite laborious. I think it’s important to the way he saw things, the kinds of loose connections he made between images and his titles, and the way he made art. His titles have a very particular ring and they’re very much about the sound linkages between the words. There’s a sense of humor that informs the titles, but I think there is a kind of auditory component to dyslexia that impacted the way he was thinking about language and titles. There is a lot of alliteration, rhyming—and not-quite-rhyming, a lot of oddball juxtaposition in his choice of words.

_5in.jpg)

It sounds like he was a very sensitive person, and when he had the means, supported many causes.

I think he was an extremely complicated person, and if you were to meet people who knew him for long periods of time, they will talk about his unbelievable level of generosity. They’ll also talk about the fact that he could be really abrasive and sometimes difficult. Let’s say there’s an element of being a bit of a scamp.

Was he one of the first to create an installation combining dance with other traditional visual arts?

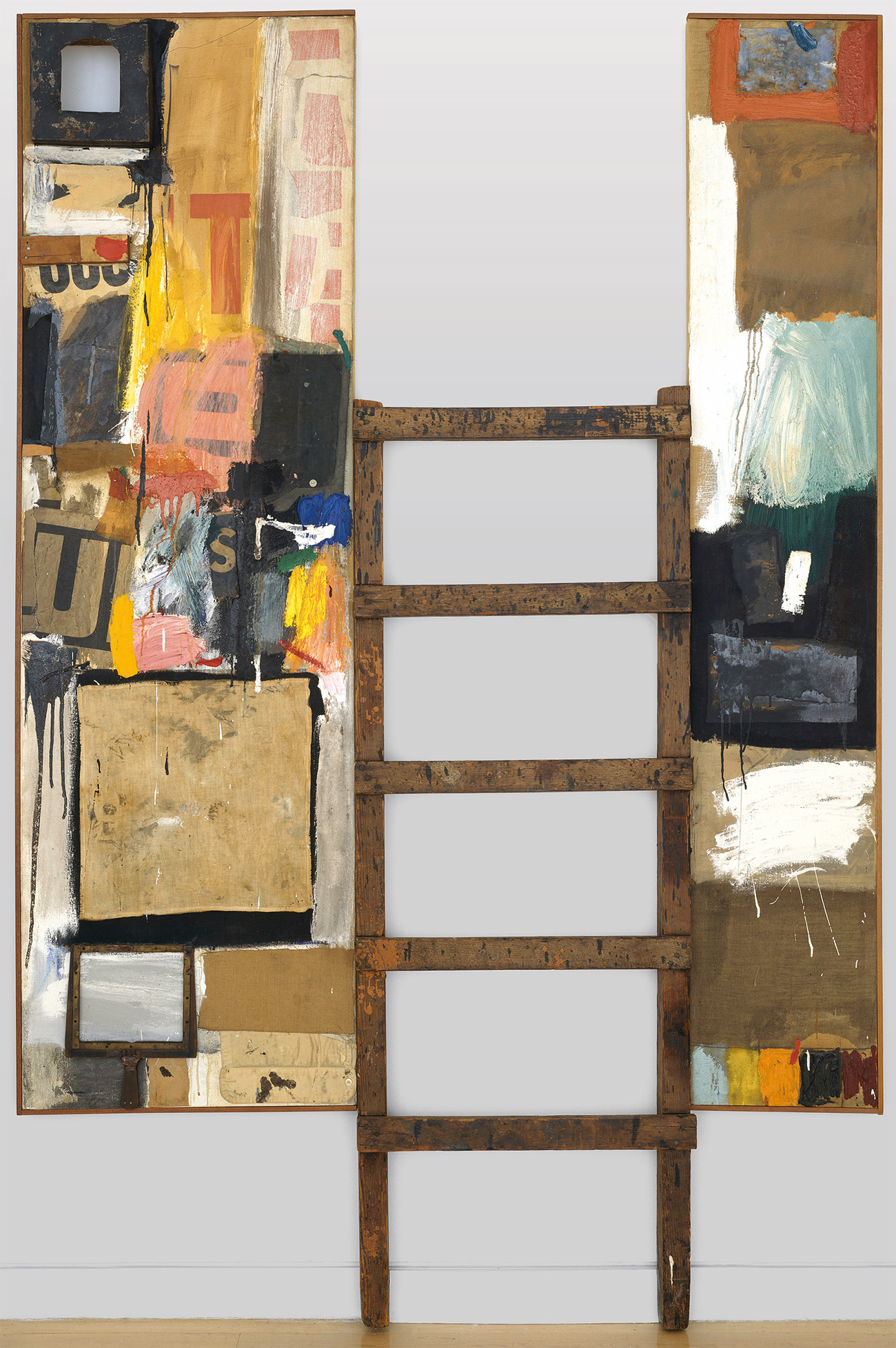

There were instances with the Ballets Russe and in the early twentieth century making sets and costumes, so there was precedent for his work with Merce Cunningham. But this was a really important collaboration because it got him to think a little bit differently about how an artwork can inhabit your personal space and how you might interact with it. There’s this transition from a painting on a wall to the Combines, which step into your space and invite you into theirs. We have on view a piece called Menusha, which was a set piece he did for Cunningham in 1954 that was right at this moment of transition from The Red Paintings to the Combines. The opportunity to see dancers moving through and interacting with sculpture ultimately found its way to the Combines and the way they are interactive and offer opportunities for the viewer to be part of the work.

The Black and White paintings came before the Combines, right?

Yes, they were part of that early experimental period, coming out of Black Mountain. He was in this phase of kind of thinking about what made art. What’s the minimum you have to put together in order for something to be called art? He was also beginning to think about the idea of interactivity, and those paintings later on have often been referred to as receptacles for light. They pick up whatever’s going on in the room; you cast a shadow on them, they change the light in the room. They kind of turn off the whole idea of the painter as the author and make you do the work. There’s a lot of work in the contemporary artworld that you have to spend some time getting to know in order to appreciate.

When did he discover photography, and how did he incorporate that into his work?

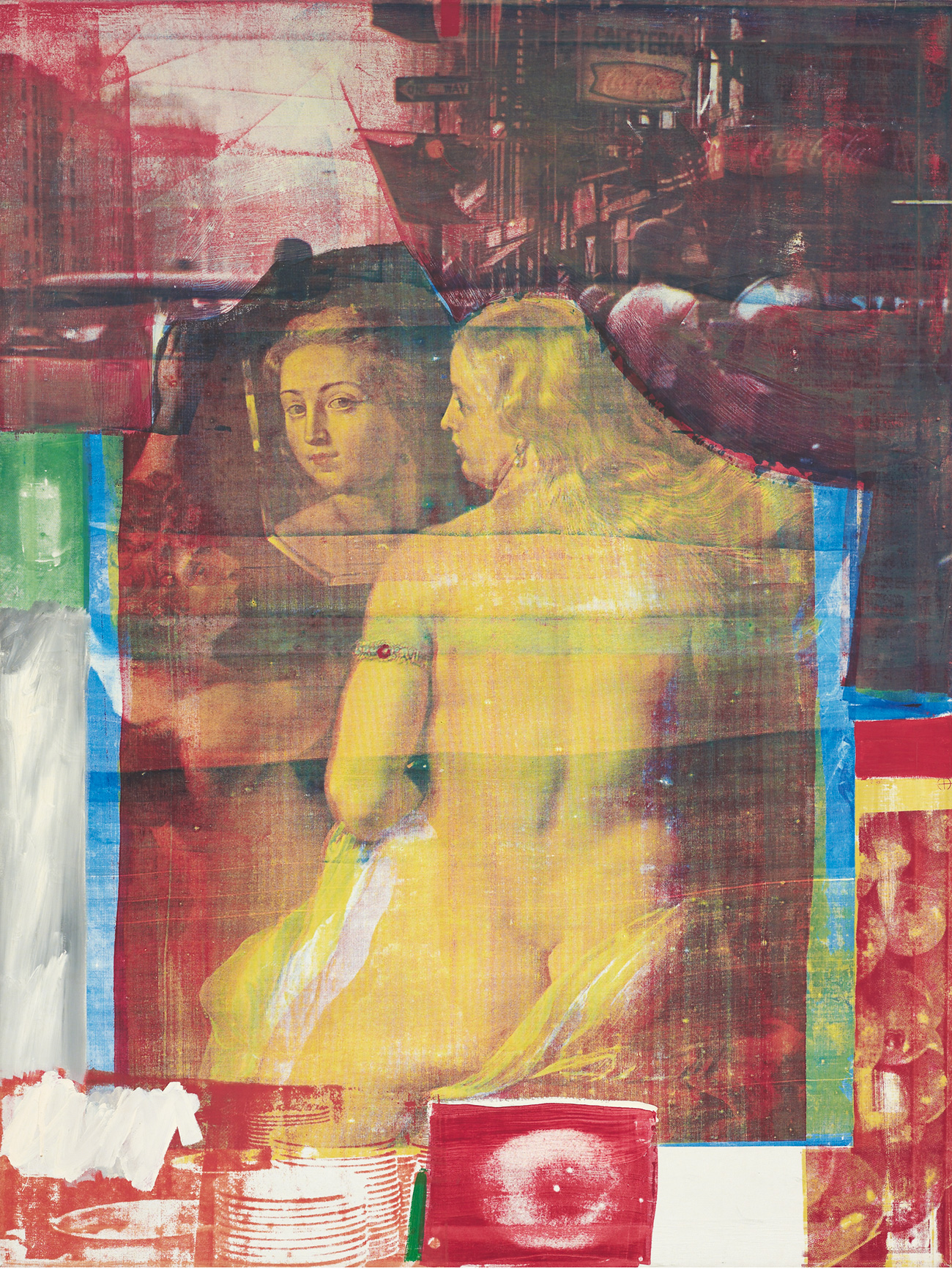

He took photography at Black Mountain, and that was his original interest. The first works he ever sold to a museum were two photographs that went to the MoMA in New York, and one is in this show. He soon transitioned to painting, and one wood-print from early on is here too! He really turned to printmaking in 1961-62. Tatyana Grosman at Universal Limited Art Edition had been twisting his arm, and with Japser Johns, who had been making prints there, convinced him to try it. He immediately began to work with lithography, but was also screen printing images on the lithographic stone from photos he got from the New York Times. He was so omnivorous, always looking for a way to break down media and use one medium in and around and through another. He became a kind of tour de force printmaker and worked with a lot of the big printmaking studios around the country. Then there’s the series of later works on metal that are made using silkscreens and resists. The metal paintings almost look like etching plates that have been inked and wiped. So the process kept finding its way into his work in other ways later on.

Did he paint anything representational?

There’s one self-portrait that I can think of, and if I’m correct, it was made in 1947.

I read an article suggesting that much of his work was forgettable, although it highly praised his process and cited his enormous influence.

My comment is that he was unbelievably prolific. I can’t think of another artist who was making art in such quantity, and that was part of his experimentation and also a part of his process. I don’t think he or anybody else thought that every single work or piece was going to transfer to the highest quality. But if you look at each series in depth, whether it was five or fifty pieces, you will always find an extraordinary subset. With whatever was his experiment, whether the medium, the series of images or color palette, he would find his way through to hit the mark. There is so much of it, and that’s why people might say that later works are not as good. There’s so much that it’s difficult to wrap your head around it. The amount of work that’s in the show is a micro-fraction of entire bodies of work. You could do an entire floor of his work made from the last ten years of his life if you wanted, it’s that vast.

Where is it all?

The Foundation has the majority, along with private collections. Museums are starting to collect it more, and we’ve recently been acquiring more

Was he considered a teacher or mentor?

He did the usual lectures, but not formally in the classroom. He always had a cluster of people around him, and once he moved to Florida, that process became circles of studio assistants.

I’m curious about his choice to move to Florida. Is it that he that he wanted to be near water, in a place that was remote?

He bought a place in New York, where the Foundation now operates. It was very social. He had a floor that his dancer friends used for rehearsals and he had parties and people in his kitchen all night, every night. It was a very hot spot, but then he went down to Florida around 1960, trying to finish some of the Dante Drawings and he just kind of found this quiet place because he needed to focus. I think he found a different rhythm, an environment that could be really productive for him. New York in the late ’60s became increasingly difficult for a lot of artists who had been there awhile. The political environment and redevelopment of lower Manhattan drove a lot of people out, so there was a whole wave of artists who left at that time. So he was kind of looking around and ended up in Captiva, and I think it really changed the way he worked. It changed the materials he worked with; it changed the circle of people around him. Yet, at the same time, he ramped up a kind of rural travel schedule where he’d spend months on the road or weeks in New York City.

It was really underdeveloped, so he was able to buy there and found a balance. He had a very deep conservationist strain and was able to buy up properties over the years and add to this swath of land, which is a long, skinny island. As you enter, it’s filled on either end with shops, hotels and houses, and a chunk of jungle in between, which is where Rauschenberg lived. He bought the property and let the people who lived there stay for the rest of their lives, though he did preserve this patch in the middle. He used all the little cottages as studios and storage rooms and places for people to stay, so there was a steady stream of people coming to his printmaking studio to help make things and get a little peace and quiet. He kept a social life going by creating this sort of compound where people would come work

I know he still found time to travel, and I’m thinking specifically of his trip to China.

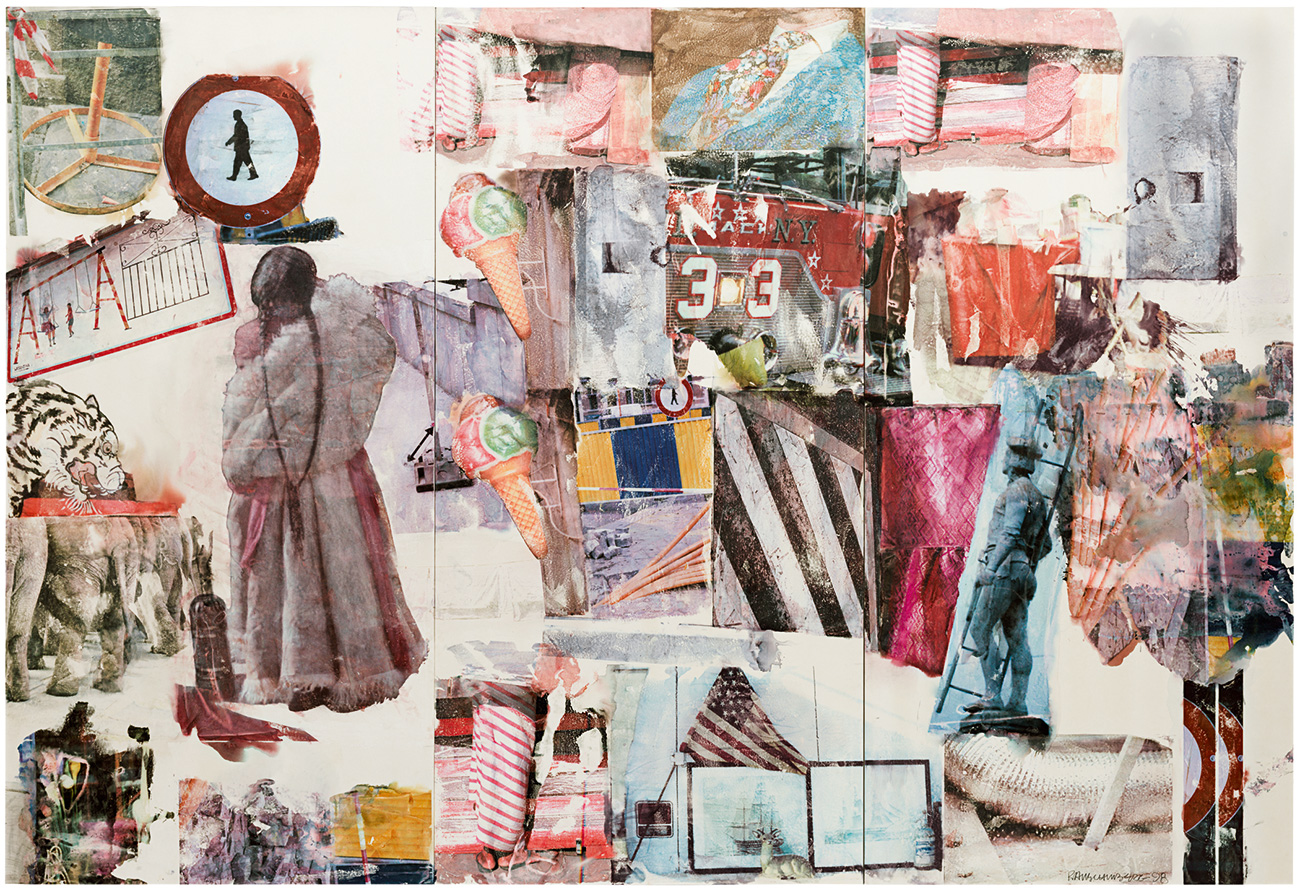

He did this whole decade-long, extremely ambitious program, called the “Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Exchange,” or ROCI for short, which happened to be the name of his pet tortoise, who was also the mascot of the program. Rauschenberg went to a number of countries, some successfully, some controversially, with the idea of going to places that did not have exposure to the western world, places where politics and conditions were difficult. He felt that art could be a global ambassador. He would go into a country, spend some time there, gather a bunch of material, take a bunch of photographs, go back to the studio, make work and then put on an exhibition which would include work made in previous locations.

The program in China was particularly important because it was around 1985, which is really early for a contemporary western artist to be there, let alone stage a major exhibition. The idea of an artist making work out of absolutely anything presented a mind-blowing experience to people who had been trained under conservative, state-run programs. We have an entire gallery devoted to ROCI and its various locations.

How will your show be different from the one I just saw in New York?

Although this will include lots of dance, it won’t be on such a grand scale, and we did make the choice to skew toward a more vintage version of dance performance rather than any recent glossy productions. We’re giving a lot more emphasis to his later work, and will have 38 works that were not in either of the two venues.

Of course, we’ll have the most recognizable works, like Mud Muse, which I understand bubbled more vigorously in New York. There’s a mud guy by the named Gunnar Marklund the Moderna Museet in Stockholm who has been in charge of the mud for decades. He’ll be here as a courier to help us mix the mud, make sure that the compressor and tubes are working properly and teach us to maintain it throughout the show.

I’ve been waiting to ask about Monogram. I love the goat, but was afraid he was too fragile to be shipped.

It had conservation treatment and been stabilized for this show. It has a case specially designed for it to travel, which is quite different from when it was here in the ’70s. It just got wheeled in off the sidewalk, with the goat hair just blowing in the breeze.

Robert Rauschenberg: Erasing the Rules is on view at the San Francisco Museum of Art November 18, 2017 through March, 25, 2018.