cody hoyt

the long view

Interview by austin mcmanus // portrait by nathan perkel

Two years ago I took my first ceramics class since high school, going into it with the confidence of a trained professional. So sure of being a natural, I thought that in little time I would be building fascinating sculptures that would woo and impress my peers. Wrong, so very wrong. Begrudgingly, I admitted failure. It turns out clay is an exceptionally unforgiving material, and without a tireless devotion, you will only be left with pots to be hidden from your friends. A few years ago, Cody Hoyt abruptly redirected his practice from illustration to clay. Seeing what he is creating, one would think he had been honing this craft his entire life. It turns out that Hoyt is a natural.

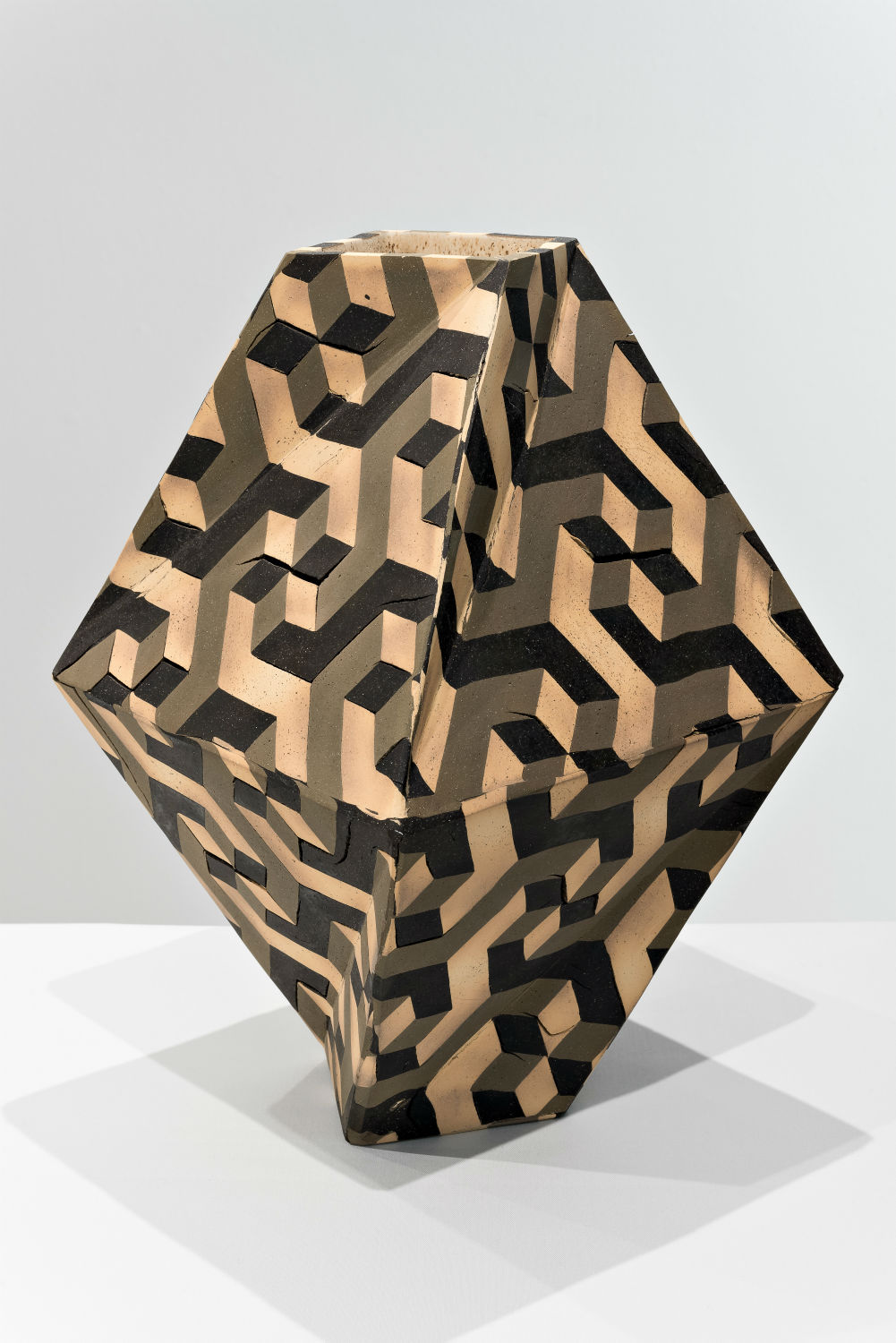

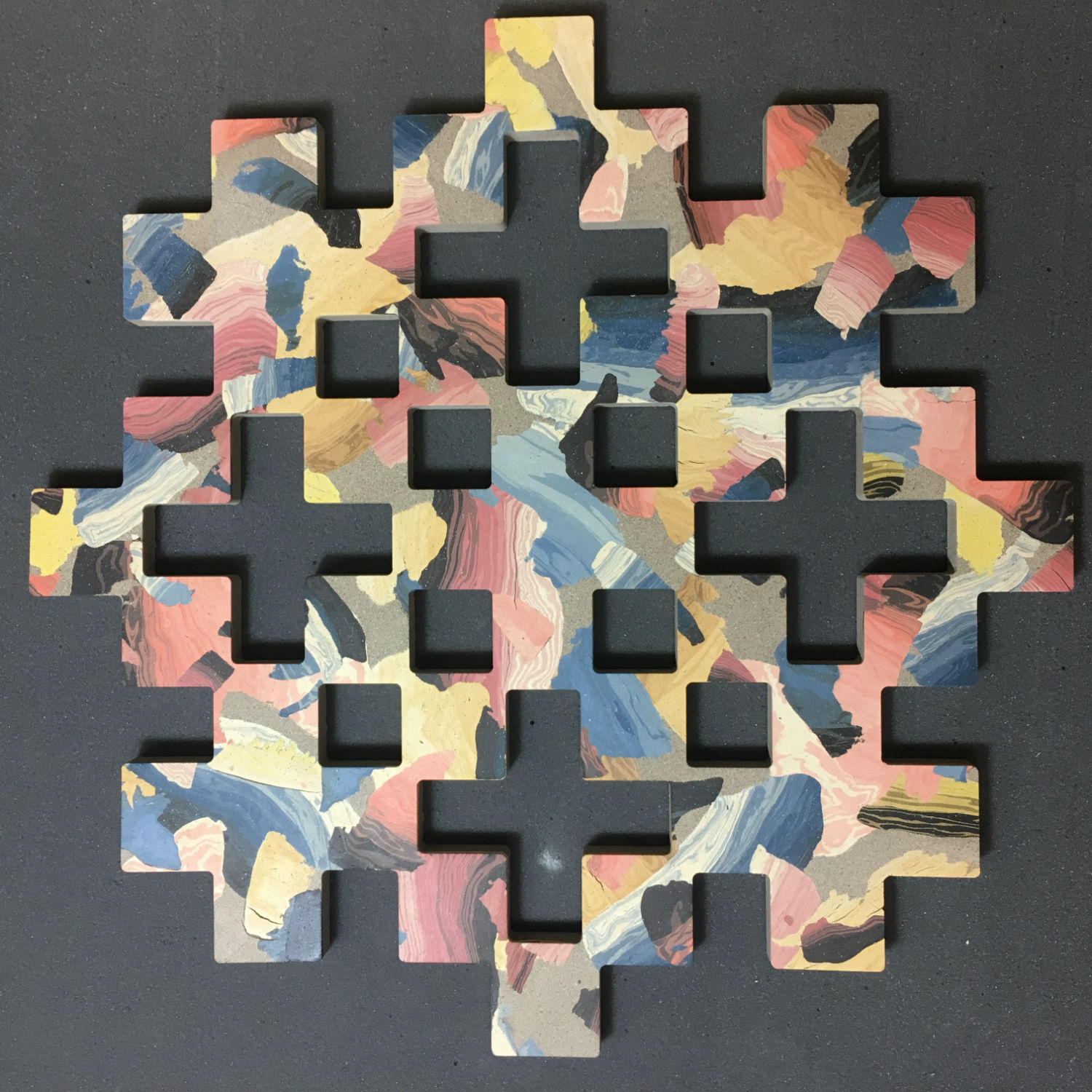

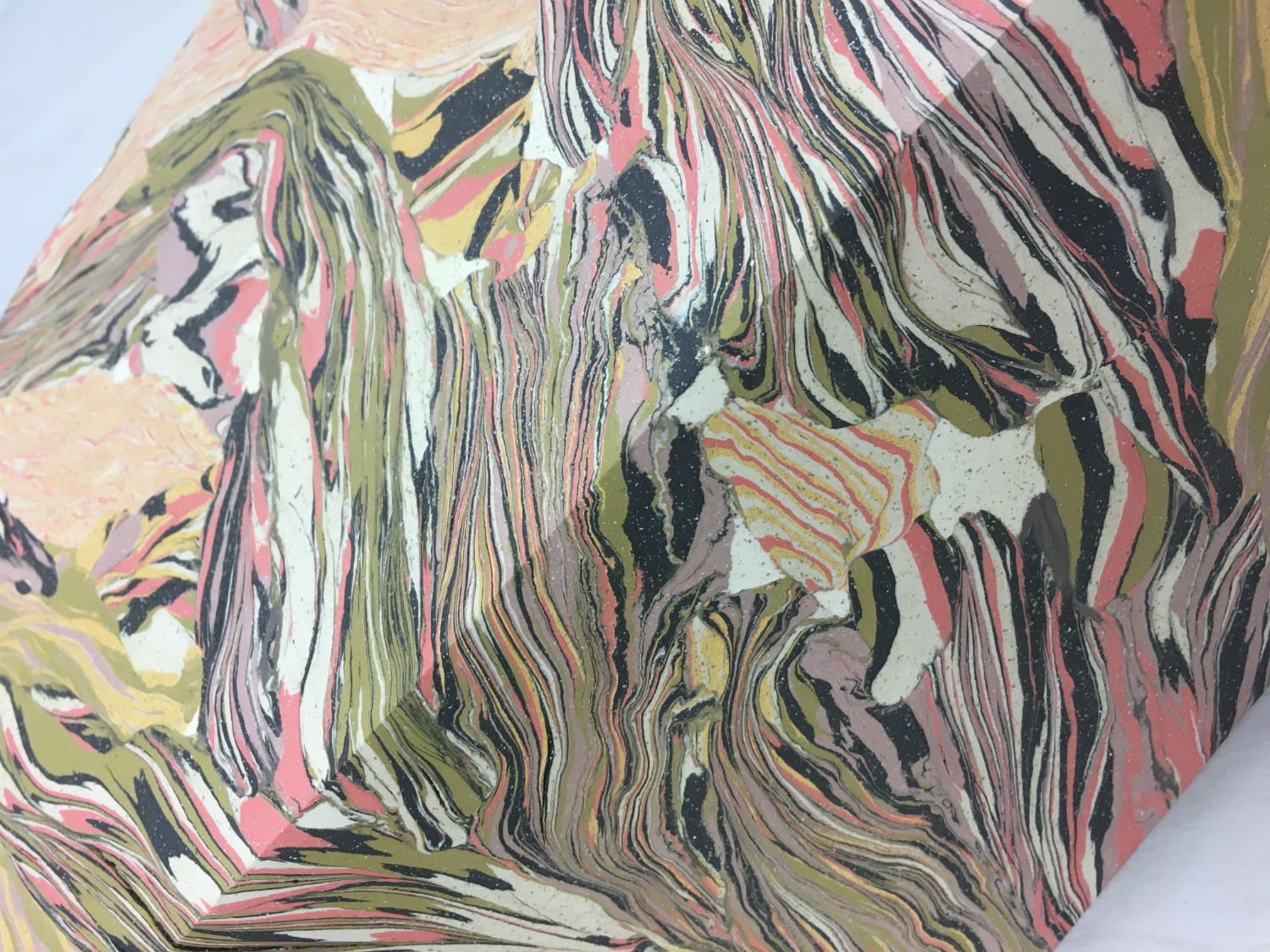

The pots, sculptures, vessels, however Hoyt’s creations may be described, are immediately recognizable. They stand on their own: each as unique as the next. The vigorous forms, shapes and designs demand attention and reflection. Above all, the inlaying techniques he employs are hypnotic. Most recently, Hoyt has been going bigger, much bigger. The scale of this newer work has introduced exciting new elements to both his practice and product. Along with the recent requirement of a few extra sets of hands to construct the work, there is also that referenced uncertainty when working with clay. “I’ve loosened up a bit about my expectations in what I’m trying to achieve. A major aspect of making and firing ceramics is that it’s unpredictable,” Hoyt explains when asked about his newer endeavors in large-scale pieces. “I’m trying to be more aware of this by embracing anomaly in the work. The best moments happen during the collision between the ultimately chaotic elements of ceramics and my attempt to assert control and order over it.”

Austin McManus: You’ve kind of darted all around this country from Florida to Massachusetts, to California, and now, to New York. How has living in New York informed your work, and what do you enjoy most? There seems to be a fairly large community of ceramicists there these days.

Cody Hoyt: New York is so loaded with history and culture. I feel like I’ve grown socially and intellectually just by being here. There’s a high concentration of artists living and working here, and an equally large and crucial network of support for the arts. I probably don’t need to list the differences between living in New York and Los Angeles. In general, though, the pace of life here keeps a fire lit under my ass and helps me to be aware that urgency belongs in the creative act.

To avoid the millions of distractions of living there, do you just lock yourself in the studio for days on end?

I miss out on cool things all the time. There’s just no way to do everything. The silver lining is that New York is perpetually amazing. There's something happening whenever I have a minute to let myself out of the cage.

What’s the longest stint you have spent without taking a break?

The problem with offering the world something with a vaguely intangible value is that there are very few times when work feels complete. I’ll take a day off when deadlines are a distant reality. After that, the closest I get to days off is starting late or cutting out early. Leaving early always feels good.

If I were to get a glimpse of “A Day in the Life” of Cody Hoyt, what would it look like?

Nothing fancy. When I’m in deadline, freak-out mode, it goes down like this: I usually wake up around 9:00 or 10:00 and eat a quick breakfast. Drink tea, pace around and plan my day. I’ll pack a few meals and snacks, eat a second breakfast and leave the house. It’s a 20-minute walk or a 10-minute bike ride to my studio. Sometimes I’ll head into the city first to pick up supplies or look at art. Then I hole up in the studio for eight or ten hours. I eat a lot of food and drink a lot of coffee. I head home when exhausted, or when it’s time to stop, often around 1:00 or 2:00 a.m. I usually spend the last couple hours of my day on the internet at home in the dark discovering music or reading movie synopses with tea or Scotch, or both.

Your work has progressed so much in just the last few years. It’s very revealing that you thoroughly enjoy what you are creating. What excites you most about the kind of work you make now?

I’m way into how adversarial it is, like any good relationship. It’s physically challenging. It rewards me periodically, seemingly on its own terms. Ceramics are so unpredictable. When something goes in the kiln, I have to almost entirely relinquish control. I have to wait for results because clay has to dry. Usually it pays out rewards over a few days at a time. Sometimes there are weeks or months of waiting before things can be touched or even looked at, let alone finished. It’s brutal.

Your entire process is analog. I really love that. Do you have any interest in constructing designs on the computer for your sculptures in the future?

I think about this a lot, because a scanner and Photoshop were integral to my earlier practice, and I’ve evolved steadily away from that over the last few years. I see the possibilities available to artists who are using new technologies and I think it’s inspiring, and in turn, I question my limited practice. The main drawback to analog is that it’s slow and laborious, but the benefit is that it has distilled my work to a point where my touch and thought process is evident in all the details.

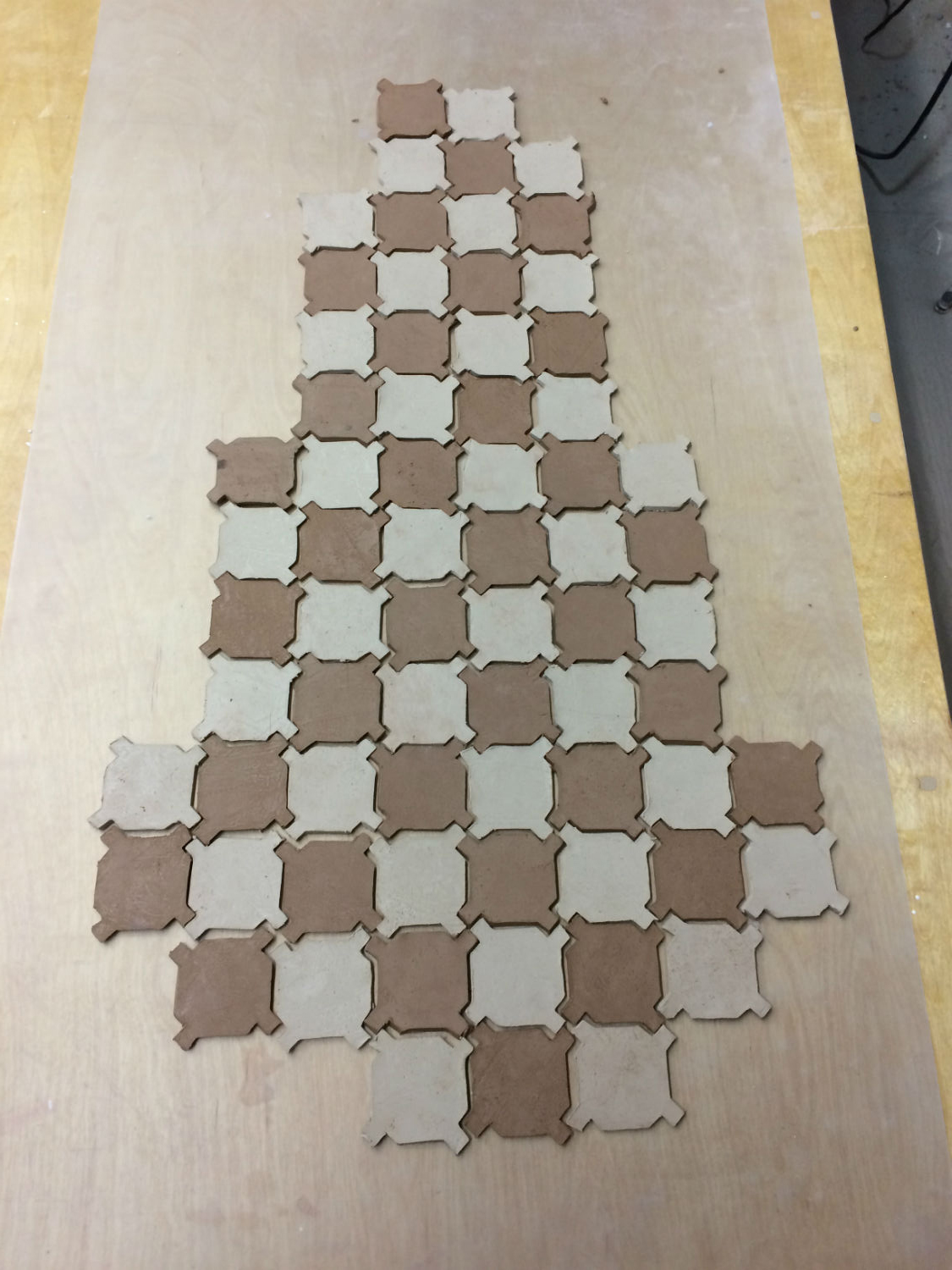

There are so many vital, long, meticulous steps on the way to the final product in your craft. Do you enjoy each stage equally, or are there some you favor?

I get excited about what I’m making during the materialization of ideas. I crave progress. Some steps are monotonous and joyless, like mixing pigment up into the white clay to give it color. That’s fun to do exactly once. Some steps are a relief to pull off, like getting the walls of a large piece up and secured. There are a few really satisfying steps, like wet-sanding fired work through multiple grades, and then the biggest psychological mind-fuck of all time is looking into a recently cooled kiln for the first time. It’s like an abusive relationship. It's either happiness or brutality, sometimes both, and you never know which is coming.

Do you ever just smash a sculpture to pieces because the end result from the kiln wasn’t to your liking? When I took ceramic classes that was basically my go-to method for 90% of the stuff I made.

Not really. I’ve never been into destroying things I’ve made and not liked. There’s always that moment six months or three years later when you pull out an old piece you never finished because you hated it and say, “This is cool. What was I thinking?” Granted, with my ceramics, there is an element of implied craft that can indicate failure or success, and I’m receptive to that, but I wouldn’t be making ceramics in the first place if I wasn’t willing to accept something different than what I set out to make. Also, the work that’s too broken to love is already too broken to smash.

Did you ever go near the wheel or was it straight to slab building from the get-go?

I’ve messed around with throwing pottery, but the wheel is just a tool I don’t need to use. It makes a good lathe, though.

There are some connections to your earlier illustration work that I can see in the current sculptures, but it’s definitely a whole different person now. Looking back, how do you feel about that work?

I do still feel a harmony with my earlier work. I’m still that artist. On one hand, it doesn’t help me to look back very far because I was young and that work wasn’t fully developed. I was searching. There are moments I really enjoy in some drawings made in the last ten years. When recent stuff is right next to the older stuff, it all makes sense together. There’s a visible through-line. Let’s say I’m still after the same things, but I’ve been alive longer, and I’ve been more focused the last few years.

By far, my favorite artist who used ceramics with sculpture was Ken Price, who I know influenced you at some point as well. He employed all sorts of experimental techniques, from sanding down layers to using commercial materials like car paint. I’m curious if you have explored many unconventional techniques or plan to do so in the future.

Unconventional for me means working backwards—coming up with an idea for a piece and then working out how to make it, and then working out how to make it better. This is the main benefit of being self-taught, that your creative choices don’t come out of an accumulation of knowledge and technique. I think of my output with ceramics as a contained body of work, and so I appreciate the parameters that are set by sticking within the conventional ceramic medium, meaning clay and glaze. When you step too far outside, the work no longer derives power from the specificity of that context. You’re in open ocean and choices are unlimited. Even though I kind of shrug off the canon of the studio ceramics movement, I believe that the work I’m making is more successful when viewed in relation to it.

For a while there, your vessels were stylishly used as homes for various succulents and cacti. Now it would appear that they have graduated in price and preciousness. Did you consider that as a potential hindrance in being taken seriously or for gallery exhibitions? You know, not being branded or categorized as, “the guy who makes incredible plant pots.”

The basic answer is that when I first picked up the medium, I had no idea what I wanted to do with it, I just wanted a distraction. I began making faceted objects almost immediately with no real goal in mind. I got super wrapped up with inventing and problem solving with this new material, but it wasn’t clear to me how it had any relation to my studio practice. There was about a year where I felt I should look at ceramics from an entrepreneurial vantage and rethink my role as a studio artist being my primary vocation. Here’s what happened, though. I made a couple of technical breakthroughs and figured out how to make the work a little bit larger. Once the scale changed slightly, it occurred to me that the ceramics weren’t as “separate” as I thought. It felt OK to say “sculpture” instead of “planter.” There’s never going to be a distinct delineation between art, craft and design so there’s no point in stressing about where your own work lands.

How long does it typically take to prepare the materials, construct, fire, glaze, etc. Basically, how long from start to finish does it take to make a piece?

More than a month for large work, but most of that time is waiting. It takes a day or two to prep materials and set up for a new piece. Maybe another two or three days to assemble the constituent parts and put the whole thing together. While it’s drying, I babysit to control the level of humidity and rate of drying. The slower the better. Once all of the moisture has evaporated evenly, it’s considered bone dry, and I can go in and edit a little bit, like define angles and sand the surface. Then it spends about 48 hours in the kiln. Once it’s cool enough to handle, I’ll spend an afternoon sanding and dressing the surface again, using various grades of diamond pads made for sanding masonry.

At your last exhibition, Fossil Record, at Patrick Parish, you created much larger work than you have in the past. What were some of the challenges with scaling up, and how many pieces ended up breaking when all was said and done?

Everything is heavy. Wet clay is heavy. Sheetrock is heavy. Making the work and putting it together requires a few sets of hands, so feeling comfortable enough to bring in help and delegate was a big step for me. The physics of making ceramics on a large scale change a bit, so the way to build something around 14-inches high might not be the way to build something that’s 28 feet. I’ve loosened up a bit about my expectations in what I’m trying to achieve. A major aspect of making and firing ceramics is that it’s unpredictable. I’m trying to be more aware of this by embracing anomaly in the work. The best moments happen during the collision between the ultimately chaotic elements of ceramics and my attempt to assert control and order.

What have been the most rewarding and challenging aspects of choosing a life pursuing the arts?

Responsibility.

When is the last time you saw a piece of artwork that truly moved or inspired you?

I was recently in Columbus, Indiana. There is a stunning amount of modern architecture in the town, and I was able to spend a few days exploring some of the buildings by Eero and Eliel Saarinen, Harry Wiese and IM Pei. Everything was deserted enough for me to have a sense of solitude and personal connection to the place. The monumental and the sacred aspect of the spaces, mostly empty churches and a library, were vastly inspiring.

What other profession do you believe you would be good at if art was not an option?

I’ve always been excited about music. I believe if I spent the same amount of time making music as I do in the studio, something substantial would come of it.