Caleb Weintraub

Spanning Centuries and Species

Interview and Portrait by Sandow Birk

Since way before the Industrial Revolution, the way things work on this planet is that people invent machines, and those machines make doing stuff easier. From fire, to the wheel, to the cotton gin, to the computer, to WhatsApp, things get done faster as technology improves the world. Caleb Weintraub fucks that up. He uses technology to create incredibly detailed and complex worlds in the computer and then, he paints them big, slowly, and painstakingly, by hand. Maybe as artists, painters sculptors, ceramicists, and printmakers, we’ve all signed up for a life of the handmade, of physical toil while creating things, using centuries-old techniques and traditions. But Caleb’s work seems to go a step beyond, in that he’s pried his way into the technological art world through the use of computer design, then yanks out his fingers, shakes them off, and starts painting again. It’s an almost incomprehensible process, but awe-inspiring to see on canvas.

The sprawl of Indiana University is the picture-perfect ideal of an American College campus. It’s a nearly 200-year-old utopia of solid grey, limestone buildings, stately and grand, situated to impress, and decorated with Romanesque and Gothic embellishments, evoking English royalty and tradition. A bubbling stream, acres of green trees, grassy courtyards and wandering footbaths usher bustling undergrads. All that, and it’s located in charming Bloomington, quintessentially quaint, with a town square complete with statuary, courthouse, old bookstore, Irish pub and resident hobo.

Caleb himself is friendly, talkative and easy to be around. In his late thirties, fit, good-looking and busy. Earnestness and sincerity convey a readiness to discuss anything and everything, though not enough time for the conversation to complete each thought line that inevitably sprouts from the main topic. He speaks quickly and directly, like the New Yorker he is, but listens, especially to his graduate students, whom he treats with respect, encouragement and genuine interest. It seems that he learns from them as they learn from him, the ideal situation on an ideal campus in an ideal American town.

In the midst of these hallowed halls and collegial activity, in the lobby of the main, grand IU auditorium, four huge murals swirl overhead, decorating all four walls high up near the ceiling. Painted in the early 1930s by the legendary Thomas Hart Benton (ironically, now perhaps known more as Jackson Pollack’s professor), they depict the social history of the state of Indiana. The images impress with their scale and formalist use of light versus dark contrasts. Benton’s swooping line work, bold colors and rendering of space twirl off-kilter, as if perceived in a drunken swoon. “They’re nice, but I’m not a huge fan,” says Weintraub as we crane our necks and spin together in the lobby.

From the grandiosity of the WPA murals and the huge auditorium, a short walk takes us inside the corrugated metal walls of the Studio Arts building, where Weintraub is an Associate Professor of Painting. There he scurries around, popping into students’ studios, attending faculty meetings, answering texts from his wife about the kids’ soccer practice, participating in group crits, and wolfing pizza until he eventually manages to squeeze some time to slip into his own studio. Finally alone, he toils away with charcoal and paper, paint on canvas, computer stylus on electronic drawing pad, paper mache, plasticine and assorted junk as he creates completely different worlds.

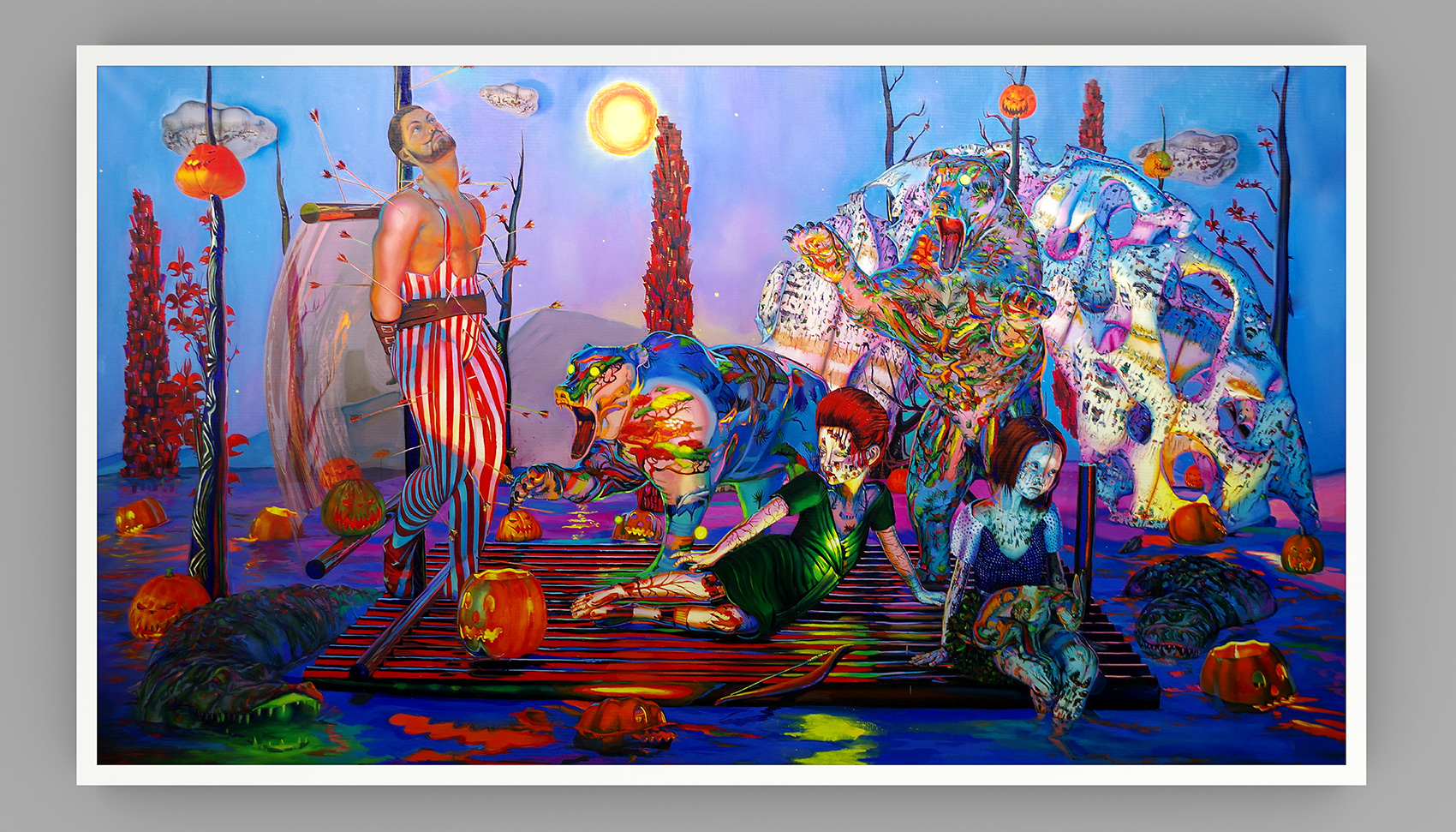

Caleb’s paintings are immediately stunning, huge and intricate, layered in depth and blasting with color. At a glance, they are reminiscent of the ubiquitous posters that were all the rage years ago, rampant with wild, psychedelic kaleidoscope patterns that blur into 3D images of jumping dolphins—if you could only figure out how to squint in just the right way.

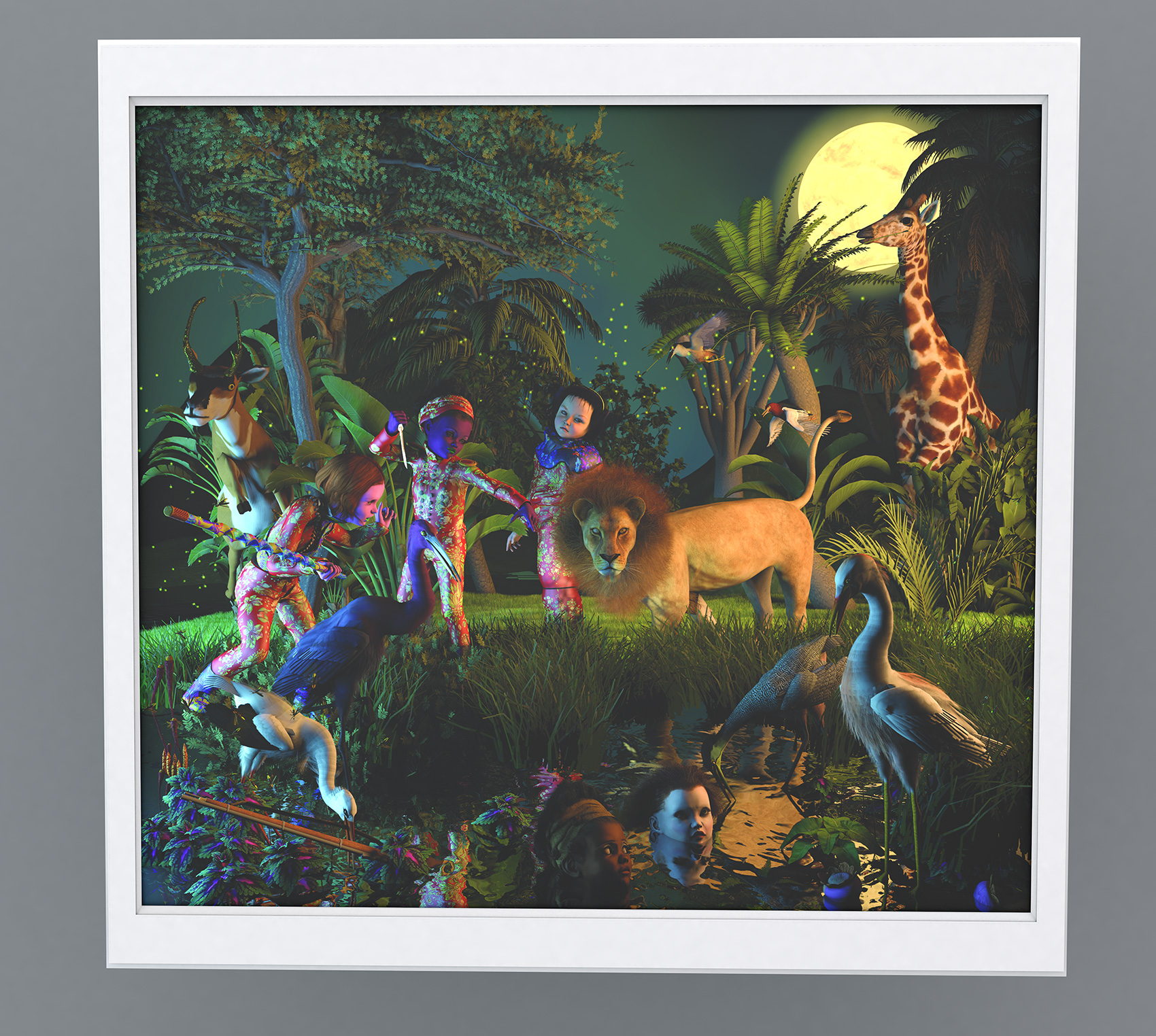

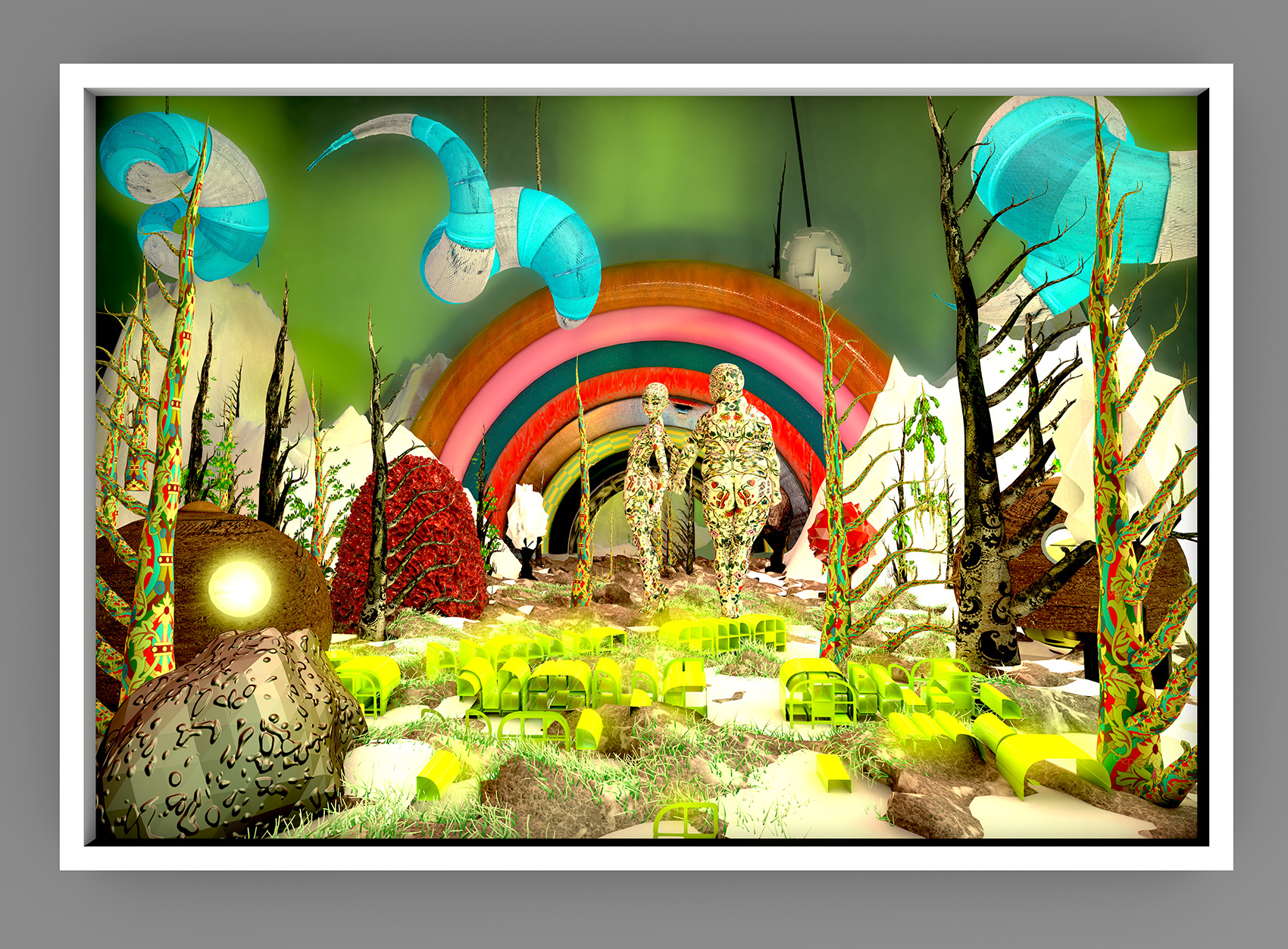

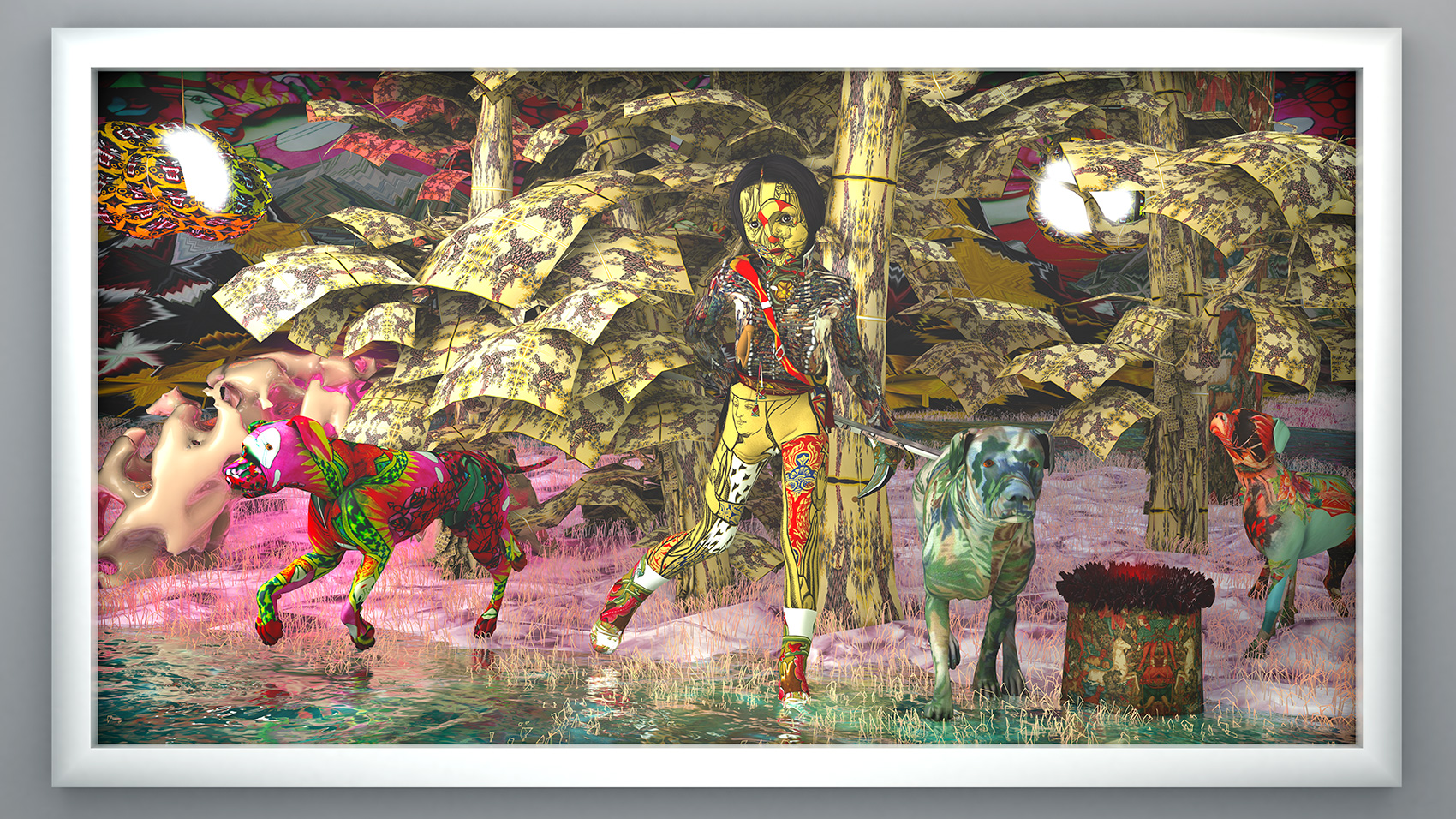

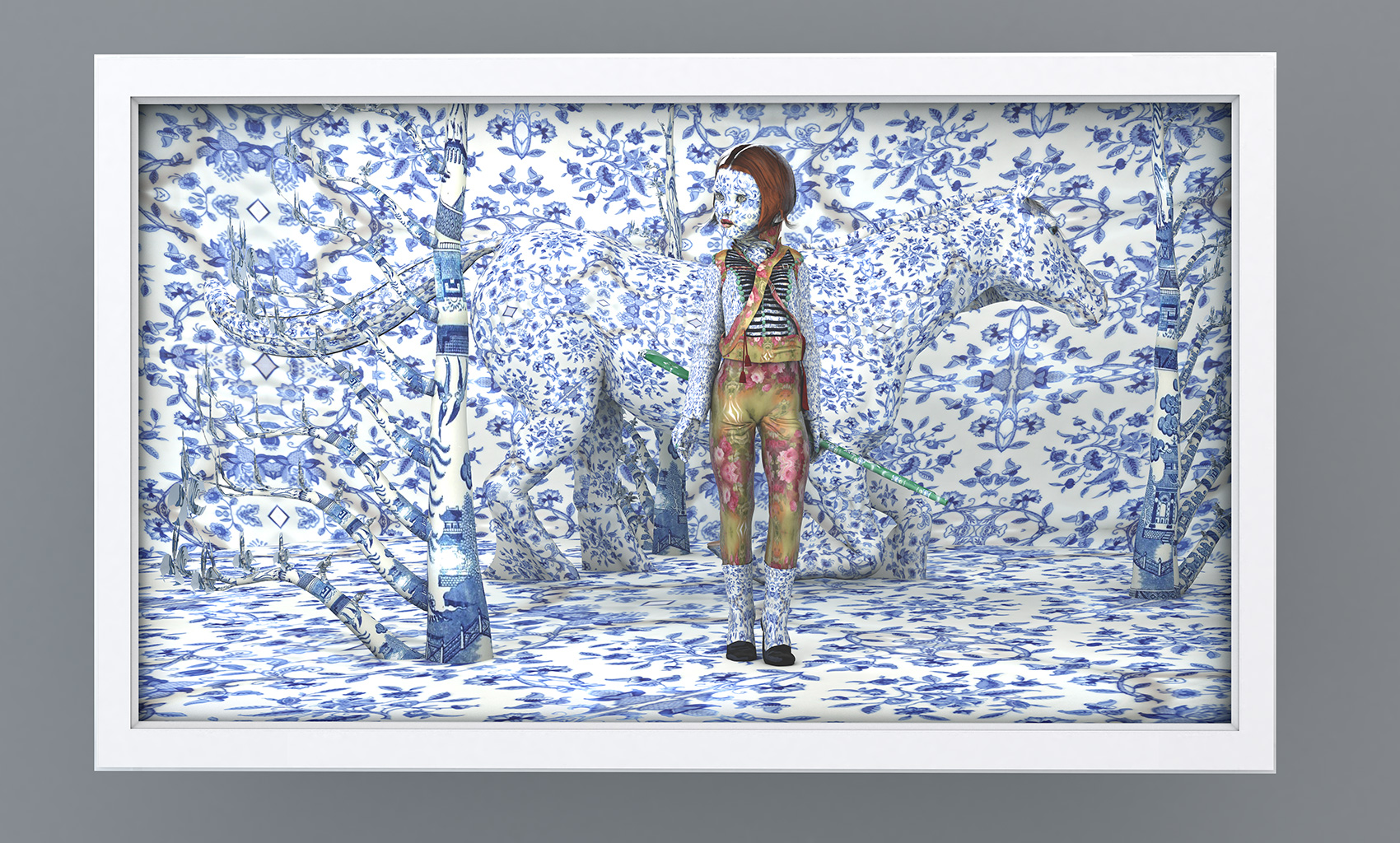

That’s only at first glance. With each minute spent poring over them, Caleb’s paintings bewitch and enthrall with more. They gradually reveal scenes where androgynous mannequin-like preteens pose in whirling forests, bearded lumberjacks are bewildered at the kids running amok in a rainbow clearing of pine trees, where Delft-decorated horses gambol about in scenes from a ballet, or where deep-sea divers wade in the shallows under meteorite skies. Getting a grasp on what you see in Caleb’s paintings comes slowly, although the more you learn, the less you might feel you understand. The paintings, large and elaborate, bring to mind the epics of historical painting.

As we talk he explains how inspiration comes from an internal visualization of space and lighting—as if closing his eyes and visualizing a diorama. Through most of his career, he would envision a three-dimensional world in his brain, pick up a pencil and start drawing, roughing in tones, lights and darks in loose sketches that would help grasp an imaginary realm. Soon, much like Thomas Hart Benton, he would find his inner, mental view of a fictional space too imprecise, and he began constructing small, quickly done tabletop maquettes of the scenes in order to better envision the spaces between things, say, the lighting cast by imaginary trees and figures. Eventually, when that wasn’t enough, he built his maquettes bigger, even life-sized, and was soon in possession of garage-sized models of strange worlds and slapdash figures. Some of these were shown in galleries, almost like elaborate shop windows displayed on Fifth Avenue at Christmas. But before long, he realized the folly of so much time and money spent, not to mention a workspace gobbled up by ever larger models originally merely intended to help making his paintings more “real.”

And thus, his conundrum: how to balance reality and dreamscape, how an internal vision sees a roomful of objects and spaces between which he mentally rearranges to create a scene in his head, but struggles to portray. His concern is about space and the accurate lighting of that space, more than the recreation of a semblance of the real world. While the imaginary stage sets exist in a dreamy, fictional realm, he wants them to ring true as believable depictions. The fanciful collides with the physical, where you feel as if you can step right in.

Although he previously never used the computer for graphic aid, eventually and, albeit, reluctantly, he decided some basic digital skills might help to grasp his internal visions. Initially intimidated and fearful of getting sucked into technology and away from the tactile, he started with simple programs and learned quickly. As Caleb soon began to use the computer to rough out his designs as virtual stage sets, he arrived at his current practice of doing a few, quick charcoal drawings to work out ideas and a sense of space, then building each element of the scene in 3D models—a tree, rock, person, or bird. Once each form is finished, a cast of characters populates the set, maybe a tree or rock here or there, completed by a campfire here and a toddler there.

Once past the hurdle of learning, the release of the computer became a joyous bonus to a hand-toiler. The boon was that he could try things and erase them, could envision a tree in blue, pink or patterned with roses. If he didn’t like any of them, the original stage was still there, intact, backed up, all of which is a path familiar to anyone who’s transitioned from the physical making of art to the screen. But that’s where his process breaks from the norm and he fucks it up. Caleb has learned his computers, his programs, his tablets, the back-up drives and stylus. When he’s done with all that, when he’s got everything as he wants it in his 3D digital world, that’s where he strays from the path and into the dense woods.

With stage set, his wonderland all arranged just so, Caleb freezes the image in all its digital, pixelated perfection—and starts to paint. As if the 3D digital file, which he can spin about and light like an early morning in Norway or summer solstice in Tahiti, were nothing but a still-life set up in your Painting 101 class; solid objects rendered, swathed in pigment on canvas.

The resulting experience is like stepping into a snow globe amid a quiet, still world, looking about through the curved plastic lens of the surrounding force field, or maybe inhabiting a fish bowl, like a miniature bubble of the sea. His paintings skip between the wacky and heroic, but are united by a tactile and exquisite use of pigment on canvas, of color and form. Narrative threads begin offstage, in the distance, winding around like tentacles that won’t untangle. As the artist’s intriguing process and vision evolve, he pushes himself and masters those mediums towards a resolution that still seems to be just beyond that bend in the glass, “or just out of sight, like the reflection you see in the barber shop, of mirror reflecting mirror, reflecting mirror to infinity, and just your own stupid mug blocking your view of what seems to be right there, behind your head; if only you could move yourself out of the way to see where it goes.”

Caleb Weintraub is Associate Professor and Head of Painting at Indiana University.