By the end, the FWP’s holdings consisted of about 300,000 items of correspondence, photos, memoranda, field reports, notes, graphs, charts, essay drafts, oral testimony, and folklore spanning 1889 to 1942. It is a rich collection of rural and urban folklore, life histories, studies on social customs of various ethnic groups, authentic slave narratives, and Negro source material gathered by project workers. In addition, drafts of publications expressed concern with the direction America was taking and with the preservation and communication of local culture. Today, these artifacts are housed in the Library of Congress and are accessible to the public through the National Archives. This became part of the foundational bedrock of the African-American narrative, and these findings continue to inform academic, critical and creative works.

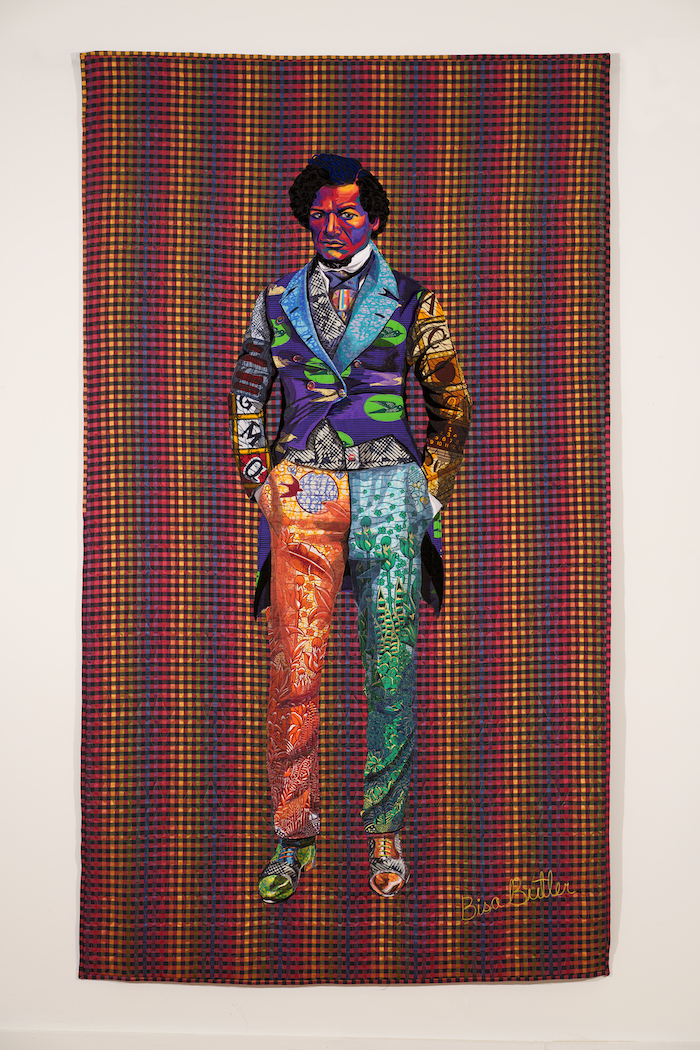

Butler finds her beloved subjects in historical, head-on, deep dives. Since her practice has grown, most of her current work consists of lesser known people who live in the shadows of history. Butler discovered the subject of her work, Africa The Land Of Hope and Promise For Negro People's of the World while rabbitholing through images. “Then it becomes a quest. Who is Emmett J. Scott? When I looked him up, he was a Black man—Booker T. Washington’s right-hand man. He was the secretary for negro affairs under Woodrow Wilson. In a sense, he is lost to history. I never heard of him before this. The year struck me: 1909. And then I thought, what makes a person have this much self-confidence? Look at his glasses, they just go on, they don’t have any rims on the side, they just go on. Look at his gloves. And looking down his nose at us. There was no way I wasn’t going to include him,” she says.